Augustin Schubinger (English)

“Augustin / Zinckenblaser / Maister” (Augustin / Cornettist / Master)

Augustin Schubinger (c. 1460–1531/32) is considered one of the most significant instrumentalists of the time around 1500. As an outstanding cornettist and trombonist, but also a skilled lutenist, he had a career that, after initial years in Augsburg, led through an activity in Florence to decades of employment at the courts of the Habsburg rulers from Frederick III to Ferdinand I. Schubinger’s prominent position is evident not least in the Triumphzug of Emperor Maximilian I: a well-known depiction of the “Chapel Wagon” shows Schubinger playing the cornett in cooperation with the chapel and the trombonist Hans Steudl; the caption for Schubinger’s portrait reads: “Augustin/Zinckenblaser/ Maister” (Augustin/cornett player/master).

The accompanying pictorial programme states among other things that „vnnder den Zÿnngken der Augustin [der maister sein solle]“ (among the cornett players, Augustin [should be the master]),[1] which makes Schubinger one of six musicians named in the Triumphzug.

As an internationally renowned and sought-after instrumentalist who participated in the musical culture of court chapels and in particular in the cultivation of composed polyphony, Schubinger represents a relatively new type of musician. The development of this type is related to a social and aesthetic appreciation of instrumental music-making that took place during the fifteenth century.[2] This is manifested, among other things, by the fact that instrumentalists, in contrast to the non-sedentary minstrels, increasingly took up permanent positions in urban and courtly centers, and that the prominent ones among them were now also discussed, appreciated, or depicted by chroniclers, theorists, poets, and visual artists. The result is that players like Schubinger become accessible in the documents, and their life and work can be at least partially reconstructed.

The Schubingers from Augsburg

Like many professional instrumentalists since the fifteenth century, Augustin Schubinger came from a family in which this profession was practiced by several members over multiple generations.[3] The first known member of the Schubinger dynasty of wind players was Ulrich (the Elder), Augustin’s father. Ulrich’s career is already typical of the social and economic rise that instrumentalists achieved during the fifteenth century through their association with urban and court institutions. Ulrich Schubinger worked as a city piper in Augsburg from as early as 1457; he is regularly referred to as “Ulrich von Landsberg” in the Augsburg accounting books, the so-called Baumeisterbücher,[4] which suggests that he probably migrated from Landsberg am Lech, only 40 km away. Thus, he belonged to the ensemble of wind players of the city of Augsburg that initially consisted of three musicians, and from 1447 onwards, four.[5] The imperial city of Augsburg, which flourished culturally and economically during the late Middle Ages, maintained this ensemble as an official representative of urban musical life, like many municipalities in southern Germany from as early as the late fourteenth century.[6]

In 1471, Ulrich Schubinger is documented in Innsbruck at the court of Duke Sigismund of the Tyrol.[7] He returned to his position in Augsburg by 1477 at the latest, where he remained until his death in 1491/92. His reputation and wealth are evidenced by the Augsburg tax records from the 1470s and 1480s, which show that “Meister” (master) Ulrich, like other city pipers, belonged to the upper 10–15% of Augsburg taxpayers.[8]

Ulrich had several sons: besides Augustin, there were Michel (c. 1450 – c. 1520), Ulrich the Younger (c. 1465 – c. 1535), and Anthon (c. 1470 – after 1511). They also achieved successful careers that culminated in positions in the service of princes of the Holy Roman Empire and in northern Italian city-states.[9] Their beginnings, of course, lay in Augsburg, where the Schubinger brothers, it is assumed, were trained by their father and initially also entered municipal service. Michel became a city piper in 1472,[10] possibly replacing his father, who is not documented in Augsburg from that year until 1476, and was probably employed elsewhere.[11] Upon returning to Augsburg, Ulrich the Elder received a payment in 1477 for “seine Sun für ain claid” (a garment for his sons).[12] As Keith Polk has plausibly argued, Michel left the city that same year, apparently to work for Maximilian I.[13] His position was likely taken over by the next oldest son, namely Augustin. In any case, Augustin seems to have regularly appeared as a city wind player in the Augsburg sources from 1481 onwards and remained in this position—apart from a short stint at the court of the Margrave of Brandenburg in 1484/85[14]]—until 1487.[15] In 1482, the third of the Schubinger brothers, Ulrich the Younger, was also appointed as a city piper. Thus, from this point on, three of the four Augsburg wind players were Schubingers for several years—a not entirely unusual constellation, as members of a family frequently clustered in courtly and municipal instrumental ensembles of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.[16]

Interlude at Friedrich III’s Court

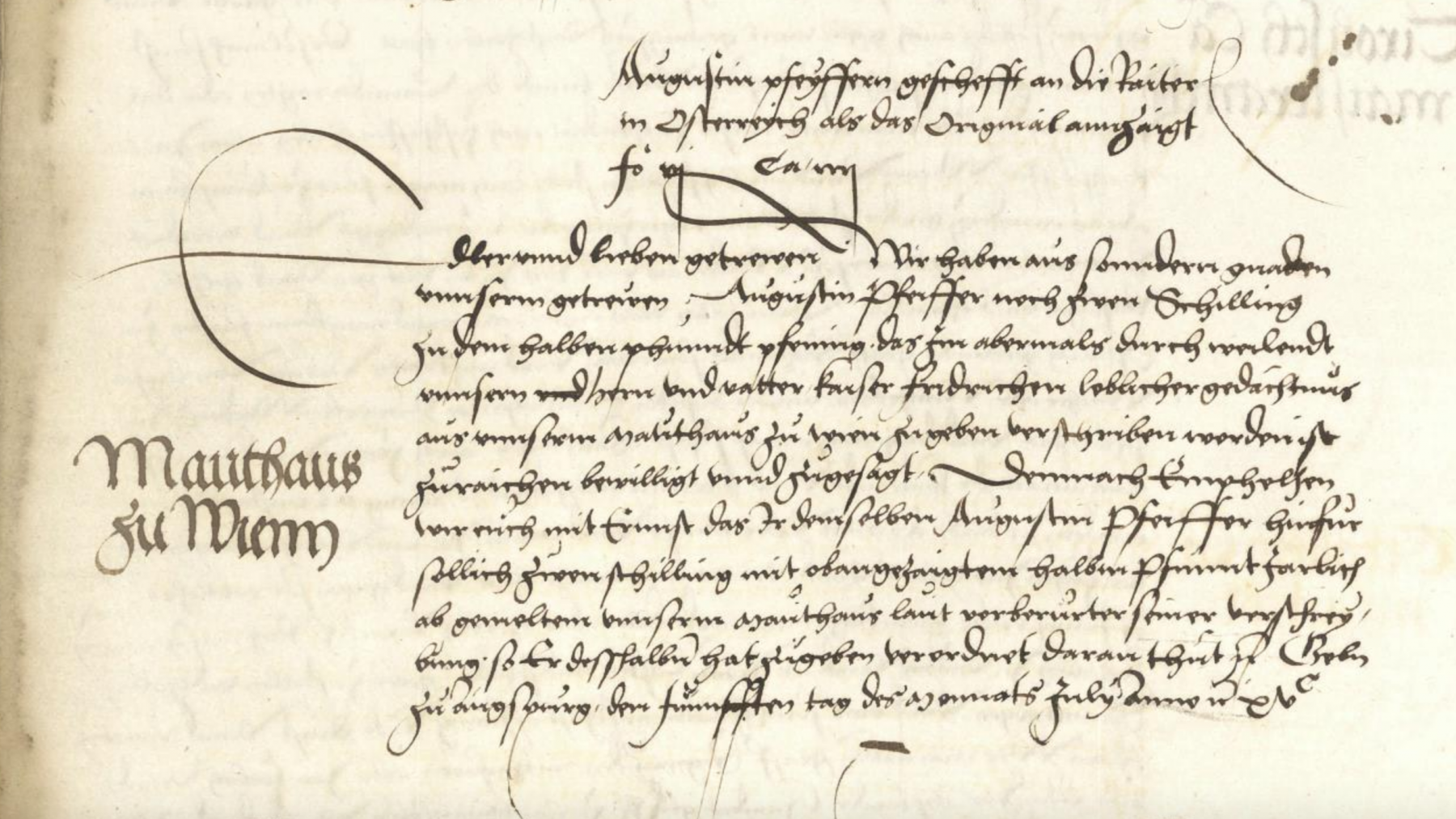

Augustin Schubinger ended his tenure as an Augsburg city piper on March 31, 1487, and entered the service of Emperor Friedrich III for two years.[17] The (currently) only known source from the Habsburg court that presumably refers to this phase of Schubinger’s career dates from the time of Friedrich’s son and successor, Maximilian I. In 1500, Maximilian promised an “Augustin pfeyffer” (Augustin piper) an increase in the allowances that had been granted by Friedrich III from the revenues of the Vienna tollhouse.

It is quite likely that “Augustin pfeyffer” (Augustin the piper) can be identified as Schubinger. Around the year 1500, the musician is indeed frequently mentioned in Augsburg sources under this designation.[18]

The allocation of revenues from the Vienna tollhouse represents a type of provision often practiced at the Habsburg court, which served as the secular counterpart to the endowment of clerical members of the court. It involved granting lay servants, in addition to their salary, income from a position in the financial administration.[19] How long Augustin (Schubinger) held this benefit cannot be precisely determined. By 1530, it had already been transferred for some time (“yetz nun langher”) to “N. Herwartt von Augspurg”, possibly a member of the well-known Augsburg patrician family Herwart.[20]

Member of the Florentine piffari

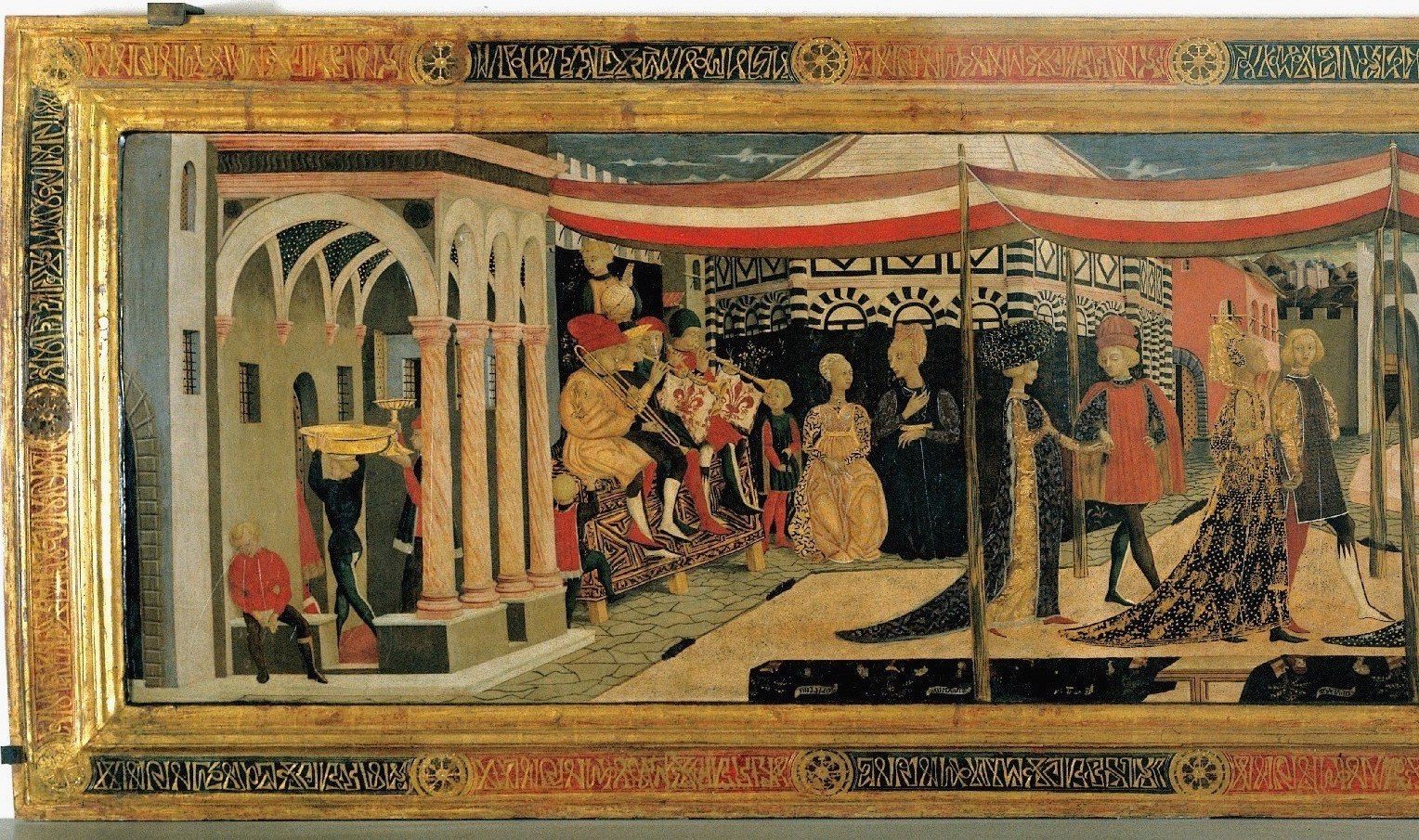

In 1489, Schubinger moved to Florence, one of the leading centres of instrumental music-making at the time.[21] The pivotal role in Florentine instrumental music was played by the piffari, an alta cappella ensemble, alongside two groups of trumpeters. Initially composed of three musicians, since 1443 the ensemble consisted of four musicians—three players of the soprano or alto shawm, and one trombonist.

Schubinger was hired in 1489 as the successor to the recently deceased trombonist Johannes di Johannes d’Alamania,[22] and thus held a position that was not only prestigious but also economically attractive. In addition to a comfortable base salary with various additional benefits, the Florentine piffari were offered the prospect of retirement benefits and the opportunity for additional income through private engagements, particularly from members of the Florentine nobility.[23]

The alta ensemble, combining shawms and a brass instrument with a slide mechanism, had become an established standard ensemble by 1450 across much of Europe, maintained by numerous cities and princes in Burgundy, the German-speaking regions, and Italy.[24] The widespread adoption of this ensemble type and its associated playing practices and repertoires was accompanied by increased transregional mobility of alta cappella players. A prominent phenomenon in the instrumental music scene of the fifteenth century was the significant presence of “German” instrumentalists in Italy. From the mid-century, musicians from “Alemania”[25] in the wind ensembles of Italian cities and courts played a leading role in their field. This phenomenon is sometimes compared in the secondary literature to the hegemony of Franco-Flemish singer-composers in the field of vocal polyphony.[26] Augustin Schubinger, his brothers Michel, who worked as a piffaro at the court in Ferrara from 1479 to 1519/20,[27] Ulrich the Younger, who was employed by the Gonzaga in Mantua from 1502 to 1519,[28] and Anthon, who also served the d’Este in Ferrara between 1506 and 1511,[29] thus represented a general condition, albeit in a particularly pronounced manner.

The trend towards recruiting German musicians can be clearly traced in Florence thanks to the abundant source material. As early as 1399, a “Niccolao Niccolai Teotonico” was employed there. In 1443, the piffaro ensemble was expanded to four players, all from the German-speaking region, specifically from Basel, Constance, Augsburg, and Cologne. That same year, the Signoria also decreed that henceforth only “forenses et alienigeni” (foreigners) should be appointed as piffari, probably referring to persons from north of the Alps.[30] While this stipulation was not consistently observed subsequently, the trombonists of the Florentine alta cappella were indeed always from the German-speaking area until the end of the fifteenth century.

Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac

The Florentine piffari performed the typical duties of urban wind ensembles: they provided music at ceremonial or representative events of the commune (such as processions or receptions of high-ranking guests), at banquets, and at public dance festivals (which, as mentioned, did not exclude the musicians from taking on private engagements). A specific feature was their integration into the patronage system characteristic of Florence under the Medici. The Medici did not maintain their own court ensembles but used their economically and politically dominant position to support the city’s instrumentalists and the chapel choirs at church institutions, primarily by actively recruiting (first-class) musicians for these institutions.[31] This resulted in patron-client-like relationships between the Medici and the singers and instrumentalists they patronised, who were effectively employed as their court musicians in addition to their official ecclesiastical or municipal duties.[32]

Lorenzo de’ Medici was decisive in appointing Augustin Schubinger to the trombonist position that became vacant in 1489, in collaboration with the Schubinger family’s network. Lorenzo, or his agent in this matter, the Florentine piffaro Jacopo di Giovanni, initially considered two individuals for the post: Bartolomeo Tromboncino and Augustin Schubinger. The young and already renowned Tromboncino ultimately declined due to his commitments to Francesco Gonzaga, and remained in Mantua.[33] Schubinger had apparently caught the attention of the Florentines during a stay in Milan in February 1489. In June 1489, Jacopo went to see Augustin’s brother Michel in search of Augustin, only to find that Augustin’s current whereabouts were unknown. However, Michel sent a letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici as a precaution, reaffirming his brother’s willingness to move to Florence.[34]

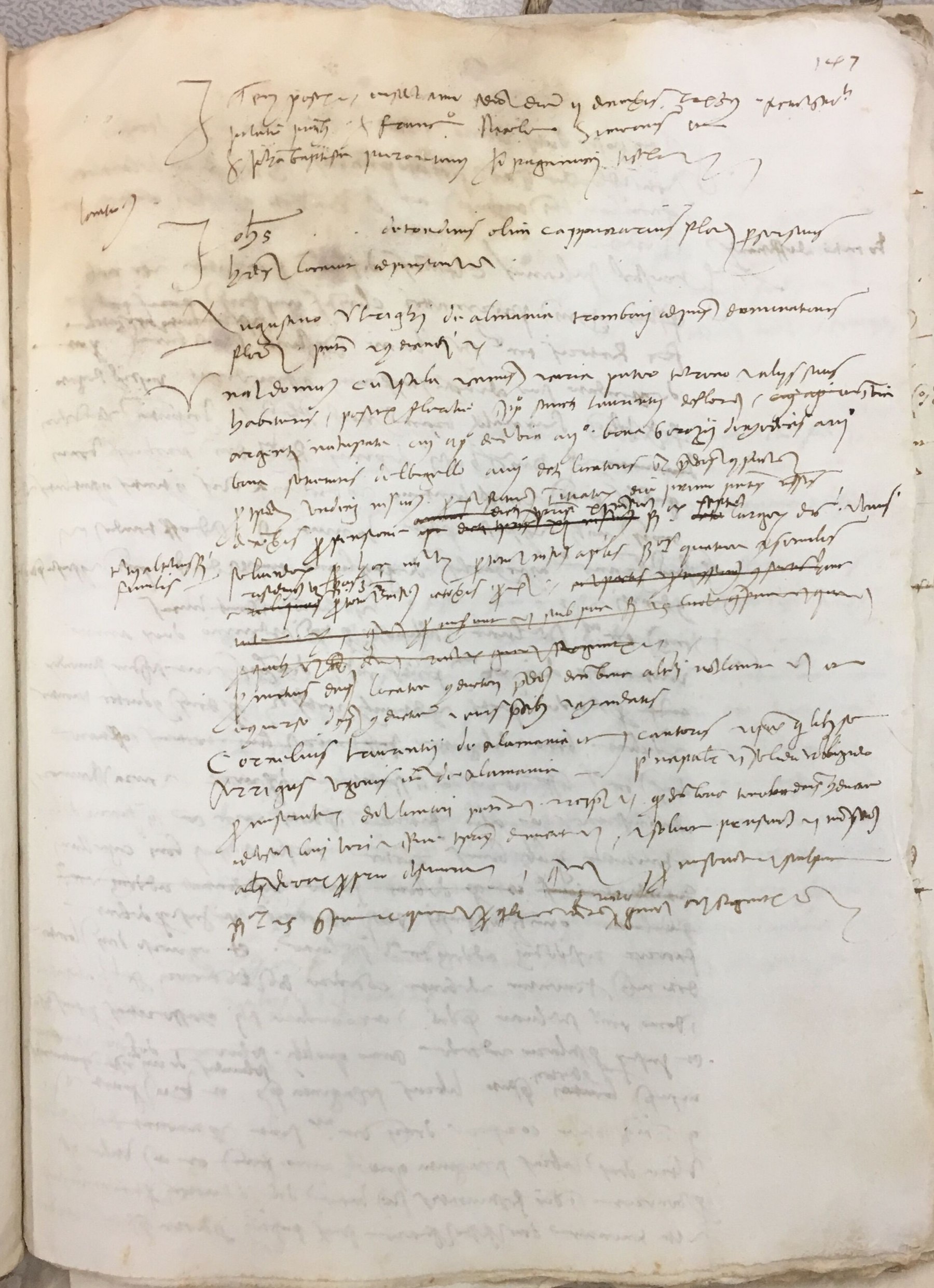

Another socially and musically significant trace of the networks in which Augustin Schubinger was involved is preserved in the form of a rental agreement recorded in December 1489 for a house on Via Argenti in the parish of San Lorenzo.[35]

[on the left:] Rent

Item afterwards etc. the same year and indiction, day 2 of December 1489.

Drawn in the said palace, in the presence of ser Francesco of Nicola of Simone and ser Giovanni Battista of Pierantonio Paganucci as witnesses.

Giovanni … Tondini, former banker, on his behalf and on behalf of his heirs leased for a rent to Augustin of Ulrich from Alemania, trombone player, currently present and residing in the territory of Florence etc.

One house with hall and rooms and courtyard, an internal well, and its other annexes, located in Florence, in the parish of San Lorenzo in via dell’Argento delimited in the first place by the said street, then by the property of Gerozio de’ Medici, then by the property of the society of the Bigallo, and finally by the [property of the] said landlord in the aforementioned boundary for the time of the next eleven months, beginning on the first day of the present month of December inscribed above for a rent of said 11 months of seven large florins and to be paid for those months for the whole month of April four similar florins, that is 3 . for the whole month of October [to be paid] for the months mentioned above

Said landlord promises not to lease the said property to others etc. and for his part the tenant has considered the present scripture and rules.

Cornelio di Lorenzo from Alamania and singers and each pledging for himself

Arrigo d’Ugo from Alamania and offering a full guarantee of repayment, promised to the said landlord to request etc. etc. that said tenant will use the property, the place etc. and observe the rental period etc. and will pay the rent etc according to the amount registered elsewhere according to the contract etc. promised.Florence, Archivio di Stato, Notarile Antecosimiano 1972 (1489), fol. 147. Edition and transcription in: Schwindt/Zanovello 2019, 3–4.

As guarantors for “Augustinus Ulrighi de Almania trombone” were – as usual in the legal practice of late medieval Florence – two “countrymen’ from the same professional milieu, namely Cornelio di Lorenzo “de Alemania,” a singer from Antwerp at the Church of Santissima Annunziata and the Baptistery of San Giovanni,[36] and “Arrigus Ugonis de Alemania,” that is, Henricus Isaac. The close personal connection between Schubinger and Isaac, expressed in the solidarity act of a guarantee declaration, suggests that their relationship was not only musically productive (» H. Kap. Textlose Kompositionen). Furthermore, their acquaintance may have been a significant factor in Isaac’s entry into Habsburg service in 1496. As Nicole Schwindt and Giovanni Zanovello have plausibly argued, it was likely Schubinger, who was already working at Maximilian I’s court at the time, who directed his employer’s attention to the composer, who was still in Florence but seeking new employment.[37]

1493/94–1499: At the Court of Maximilian I and Philip the Fair

Augustin Schubinger was last recorded in Florence in 1493.[38] Soon after, he left the city and returned to Habsburg service. The exact timing of this transition is unknown, but it is assumed that Schubinger’s departure from Florence was due to the crisis the city faced following the death of Lorenzo de’ Medici in 1492, which significantly impacted the city’s musical life. In 1493, key musical institutions such as the chapels at the Cathedral, San Giovanni, and Santissima Annunziata were dissolved. Augustin was first documented as a musician for Maximilian I in February 1495.[39] It is possible – even if it cannot be proven – that he was among the cornett and trombone players who performed at the wedding mass of Maximilian and Bianca Maria Sforza on March 16, 1494, in Innsbruck, as described by an envoy from Ferrara (» I. Kap. Maximilian in Innsbruck).[40]

Following the common practice of Habsburg rulers to make their servants available to other members of the dynasty for shorter or longer periods, Schubinger transferred to the service of Philip the Fair in 1496/97.

It cannot be definitively proven that Schubinger’s move was related to Maximilian’s financial distress at the time, which forced him to partially dismiss his musicians, partially “outsource” them, or finance them from sources other than his Innsbruck Treasury, but this would not be implausible.[41] In any case, Schubinger received a one-time payment in January 1497 for the “bons et agréables services” he had rendered to Philip the Fair,[42] suggesting that Schubinger’s presence in the Low Countries began before the end of 1496/97. This makes the previously expressed assumption likely that he was the “teutonicus” who played the cornett (“cornu”) at a mass in the collegiate church of Sint Goedele in Brussels in 1496.[43]

A little later, on March 10, 1497, Schubinger was permanently appointed as “varlet de chambre et joueur des cornet et du lut,”[44] and consequently appears under the “pensionnaires” in the “Ordonnance de l’hôtel” of Philip, issued on that day.[45] Both indicate a privileged position: As a pensionnaire, Schubinger received an annual fixed salary independent of his presence at court, amounting to 270 livres, paid in four instalments every three months. This distinguished him from the majority of court employees, who received a daily wage only for the days they actually spent at court.[46] Furthermore, he held the position of va(r)let de chambre, which was granted to specially qualified individuals such as craftsmen or artists, representing the highest rank attainable at court and including direct personal interaction with the prince.[47] This was presumably a necessity given Schubinger’s appointment as lutenist, exercising a musical activity typically situated in a more intimate setting.

1499–1500: Back with Maximilian I

Augustin Schubinger returned to Maximilian’s court in 1499. He may have joined his new (and former) employer at the beginning of the year while Maximilian was in the Low Countries.[48] However, Schubinger is documented in Augsburg as “augustin pfeiffer […] des Ro. künigs diener” (Augustin piper […] servant of the Roman king)[49] at the end of November or beginning of December, and from the end of the year, his whereabouts matched the royal itinerary. Maximilian spent the winter from November 1499 to February 1500 at Innsbruck. On 23 January 1500, Schubinger received a payment there “zu zerung vnnd vnnderhaltung auf seinen diennst” (for sustenance and maintenance for his service).[50] In January 1500, the Milanese envoy Erasmo Brascha tried unsuccessfully to lure the virtuoso, highly esteemed by Maximilian and his entire court, to Mantua.[51] From June to August 1500, Schubinger received additional payments from the court, “auff seinen soldt” (for his salary) and for Liefergeld, that is, a reimbursement of expenses, in this case to cover the costs of horse maintenance.[52] It is noteworthy that other musicians of Maximilian, the “Pusawners” (trombonists) Peter and Jörg Holland, Jobst and Jörg Nagel, also received Liefergeld between April and September,[53] and that these payments were made in Augsburg.[54] Here, a Reichstag (Imperial Diet) opened on April 10 and concluded five months later. Apparently, Maximilian brought not only his chapel and the trumpet corps but also his “Pfeifer” (pipers) to this event, which, like all Imperial Diets, served also as a stage for the ruler’s self-representation.[55] These pipers likely formed an old-fashioned alta cappella or perhaps even a “modern” cornett and trombone ensemble (» Kap. „Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang“). The participation of the wind players, specifically a cornettist (perhaps Schubinger), is documented at the solemn High Mass on Pentecost Sunday (June 7) in Augsburg Cathedral. Clemens Sender’s Chronicle of the City of Augsburg reports that “des kinigs canterei” (the king’s chapel) had sung “mit mancherlei trumethen, pfeiffen und orgeln” (with various trumpets, pipes, and organs).[56] Two days later, the “k. Maj. Sinngerknaben” (His Royal Majesty’s choirboys) were specially honoured “so am Pfingstag in den Zinghken gesunngen haben” (for singing with the cornetti on the feast of Pentecost).[57]

1500–1505: Back at the Burgundian Court

Only two months after the end of the Augsburg Reichstag, on November 2, 1500, Schubinger was again employed as a “joueur de lut” (lute player) by Philip the Fair, as in 1497, with an annual salary of 270 livres.[58] This began a second period of more than five years of service at the Burgundian court,[59] characterized not least by participation in the Archduke’s first journey to Spain. Philip and his entourage set off from Brussels on November 4, 1501, and reached Spain at the end of January 1501. In the spring of 1503, they took a longer return journey that led through France and Savoy to the Tyrol, where Philip met his father in September, and ended with their arrival in Mechelen in early November 1503.

For the first time, several reports from these years specifically relate to certain performances by Schubinger. We know that he played at a service at the collegiate church of Sint Rombout in Mechelen on Candlemas 1501.[60] More importantly, through a description of Philip’s journey to Spain written by Antoine de Lalaing, a chamberlain at the Burgundian court, we know about Schubinger’s involvement in two significant events: the High Mass on Pentecost Sunday (May 15) 1502 at the Cathedral of Toledo, attended by Philip, his wife Joanna, and her parents Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile; and the Mass on Easter Sunday (April 16) 1503 in Bourg-en-Bresse, the then residence of Philip’s sister Margaret of Austria and her husband, Duke Philibert of Savoy.[61]

Lalaing’s description of both occasions explicitly mentions that the singers and Schubinger played the cornett together: “avoecq les chantres jouoit de son cornet maistre Augustin lequel foisoit bon à ouyr” (together with the singers, Master Augustin played his cornett, which was beautiful to hear). This provides the second oldest clear evidence for the then-emerging practice of combining vocalists and wind players after the payment record for the “in den Zinken singenden” boys (singing with the cornetts) at the Reichstag of 1500 (» H. Kap. „Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang“). It is remarkable that Lalaing even reported this at all, since contemporary chroniclers usually omitted detailed information about musical performances, let alone the names of the musicians involved. Aside from Schubinger’s reputation and the quality of his playing, it was probably the novelty and thus the unfamiliarity of this practice that drew Lalaing’s attention.

So far, the secondary literature has assumed that Schubinger accompanied Philip on his second journey to Spain, which began in January 1506; during this trip, Philip died unexpectedly on September 25. This assumption is based on the identification of Schubinger with Augustin de (la) Scarparye (also Scarperye, de Carperie, etc.), a trumpeter who appears in several documents of the Burgundian court from 1501 to 1506.[62] However, this identification is incorrect. These are two different people, as evidenced by the Ordonnance de l’hotel issued by Philip on the occasion of his first journey to Spain in 1501. In this document, both musicians are listed—Augustin de Scarparye (possibly referring to Scarperia near Florence) among the trumpeters, and Schubinger separately among other instrumentalists, namely three “musette” players and a fife-drum pair.[63] While Augustin de la Scarparye is repeatedly documented in connection with Philip’s second journey to Spain, there is no evidence that Schubinger was at the Burgundian court from January 1506 onward. In fact, he was back in Germany by early June at the latest, as indicated by a payment from the city of Nördlingen to him and an unnamed trombonist:[64]

Back at Maximilian I’s Court

Schubinger must have returned to Germany before June 1506 to re-enter Maximilian I’s service. The Nördlingen source refers to him as a musician of the “king,” which in the context of a Swabian imperial city likely meant the Roman king, i.e., Maximilian, and not the King of Castile. Furthermore, a letter from Lorenz Behaim to Willibald Pirckheimer from June 1506 explicitly mentions the “Roman king” as Schubinger’s employer (» H. Kap. Eine süddeutsche Humanistenkorrespondenz).

As often discussed, Maximilian’s itinerant lifestyle and governance, which still adhered to the medieval “traveling kingship” tradition, required similar mobility from his musicians. However, this did not mean that the court musicians were always in the monarch’s retinue. Instead, they often travelled to his various destinations ahead of or behind him, or they made longer or shorter stops at different locations separate from the main court camp, remaining “on call” to be summoned as needed. This high degree of mobility applied not only literally but also figuratively Only on exceptional occasions such as Imperial Diets did Maximilian gather all his musicians around him. The norm was that the emperor surrounded himself with parts of his court music, that is, with specific ensembles or groups of musicians or even just individual musicians, depending on the occasion, necessity, or desire.[65]

It can not only be assumed in principle that this flexible utilisation also affected Schubinger, but can be traced in concrete terms, at least in some cases, thanks to a comparatively denser source situation. Examples include the years 1507/1508 and 1512.

1507/08: Nördlingen – Augsburg – Constance – Innsbruck – Mechelen

Maximilian arrived in Alsace from Innsbruck in mid-February 1507, where he stayed until his departure to the Imperial Diet in Constance in April, in time for its opening on 30 April. Meanwhile, Schubinger was in Nördlingen around February 19 and a month later in Augsburg.[66] Although his name is not explicitly mentioned in any sources related to the Imperial Diet, it can be assumed that Schubinger was summoned to the assembly in Constance sometime during April or May. Maximilian summoned his entire court music to this event, including the full chapel (which likely arrived in Constance as early as February), the trumpet corps, and players of cornetts and trombones, who performed at banquets, a fireworks display, and church services in conjunction with the chapel.[67] After the closure of the Imperial Diet in July 1507, Maximilian set off for Innsbruck, while the chapel began a long stationing in Constance, lasting until May 1509. This period proved particularly productive; Henricus Isaac began working on his Propers cycle known as Choralis Constantinus).[68] Only in two cases is there more detailed information about the whereabouts of the instrumentalists after the Imperial Diet. Paul Hofhaimer settled permanently in Augsburg in 1507 on Maximilian’s orders.[69] Schubinger did not stay long with the chapel, since his accommodation and hospitality costs were reimbursed by the Tyrolean Treasury in Innsbruck at the end of November 1507.[70] At this time, Maximilian was no longer in the Tyrol, but had been traveling in the Allgäu since early November. Schubinger’s initial destination is unclear. However, an undated payment recorded in the account book of the city of Mechelen, covering expenses from November 1, 1507, to October 31, 1508,[71] suggests that he rejoined the court camp during the second half of 1508, when Maximilian was in the Netherlands for the preparation and conclusion of the League of Cambrai.

1512: Innsbruck – Trier – Mechelen

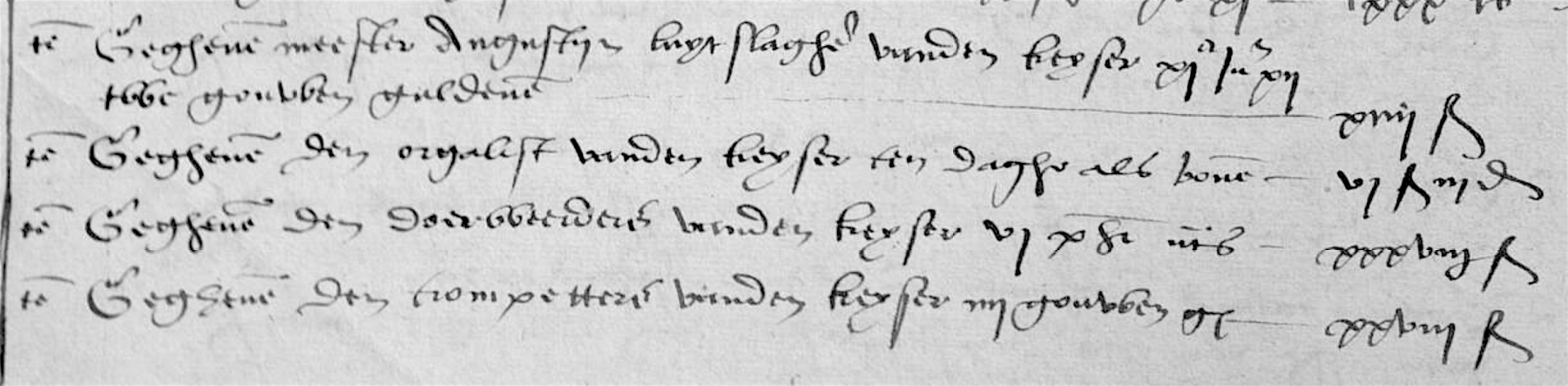

At the beginning of 1512, Maximilian was in Upper Austria, where he also took his chapel.[72] He then travelled through Bavaria to Trier, arriving in mid-March, a month before the opening of the Imperial Diet on April 16. Schubinger is documented in Innsbruck at the beginning of that month, where he received reimbursement of expenses from the Tyrolean Treasury on April 8.[73] It can be assumed that Schubinger was called to Trier around this time. This is supported by the fact that the Imperial Diet Chronicle of Peter Maier, a secretary to the Bishop of Trier, reports on church services of Maximilian I’s chapel with instrumental participation, particularly a mass on Cantate Sunday (May 9) “die ist discantiert” (that was sung polyphonically) and “darinn mit zincken vnd basunen geblasen” (played with cornetts and trombones).[74] In the second half of May, Maximilian departed from the Imperial Assembly to the Netherlands. Another payment from the city of Mechelen to “meester Augustyn luytslagher vanden keyser” (Master Augustin, lutenist of the emperor) confirms that Schubinger (along with his trumpeters and an unnamed organist) accompanied him.[75]

In mid-July, the emperor left the Netherlands for Cologne, where the Imperial Diet had been moved from Trier. He arrived on 16 July. After the Diet concluded at the end of August, Maximilian remained in Cologne until early November. He then travelled to Alsace, where he spent most of the time until March 1513. Whether Schubinger was part of the emperor’s entourage in Cologne is unknown. In any case, they had gone their separate ways by November at the latest, when Schubinger made another stop in Augsburg.[76]

Augsburg with Citizenship

Since the end of his service for Philip the Fair and his return to Maximilian I’s court, Schubinger was frequently documented in Augsburg. He stayed there partly with his employer but also several times independently of the main court camp.[77] This corresponds to a known pattern, since Augsburg, alongside Innsbruck, was the preferred place where Maximilian’s musicians, sometimes individually, sometimes in smaller groups, set up their quarters between their stays at court.[78]

Although there are no indications that Schubinger, during his service with Maximilian, settled permanently in Augsburg, as Paul Hofhaimer did from 1507, a lasting closer connection to his hometown can be assumed. He retained his citizenship,[79] and at least periodically, his family probably remained in Augsburg during his absence. This is suggested by the fact that only his wife appears in the tax records for many years.[80] Being recorded in the tax books usually required personal presence in the city, at least during the tax survey conducted in October/November.[81] It is thus plausible that Schubinger’s wife remained in Augsburg while he was away. Furthermore, the tax books, organized by tax districts, reveal that the Schubingers lived at the Rossmarkt in the Jakobervorstadt until 1505. By 1507 they had moved to the area known as “Kappenzipfel”, where the famous Fuggerei was built around 1520.[82]

It is noticeable that the tax records for Schubinger and his wife record that no amount was to be paid, or the note “dat nihil” (pays nothing) is found.[83] The reason for this cannot be definitively determined, but it is possible that Schubinger – like Paul Hofhaimer – enjoyed an imperial tax exemption.[84]

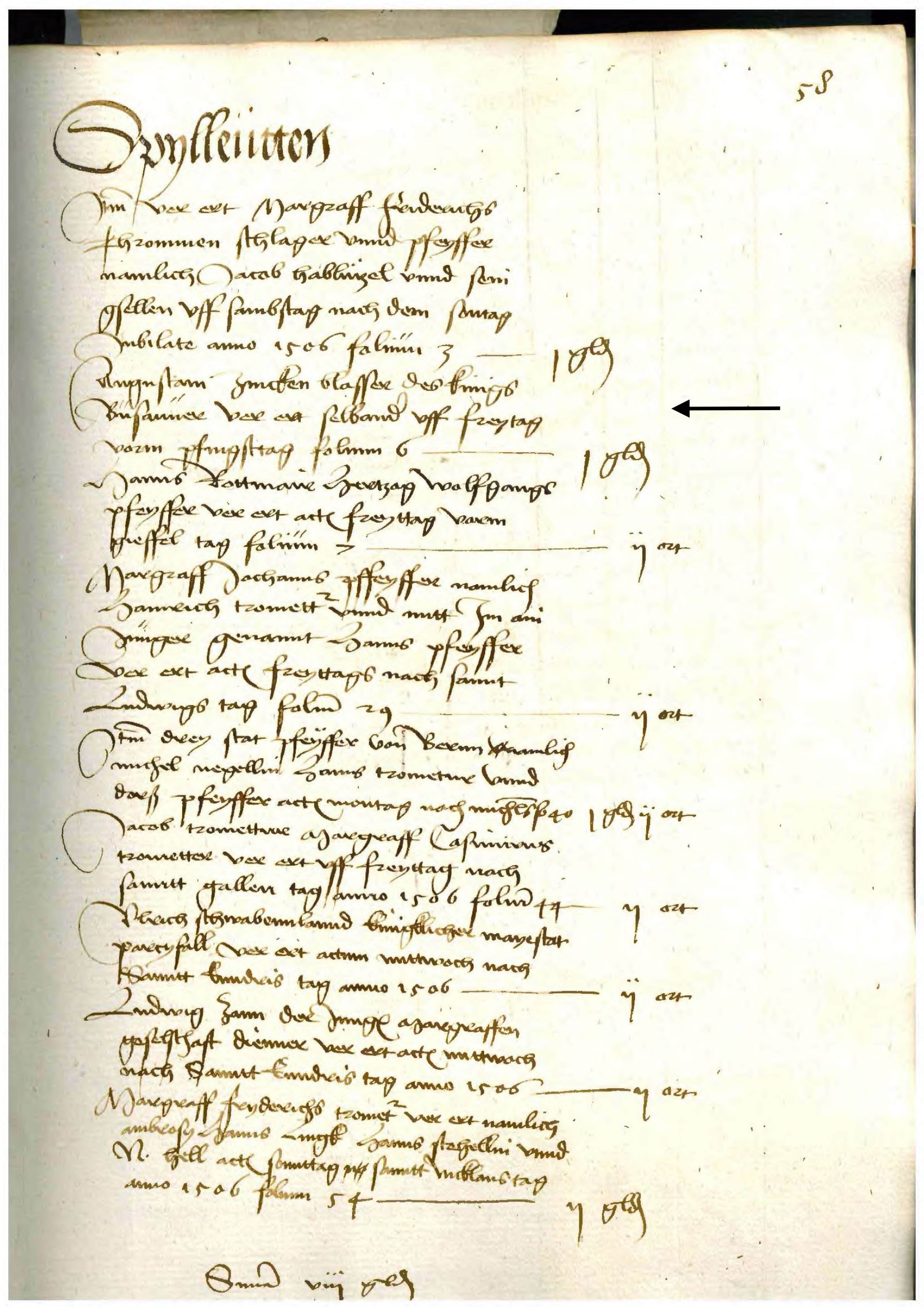

We know of Schubinger’s stays in Augsburg primarily through the city’s expenditure books, the so-called Baumeisterbücher. These books record numerous payments to servants, especially musicians of princes of the Holy Roman Empire, particularly Maximilian I, each year under the category “varende leute” (travelling persons).[85] It is not entirely clear what prompted the city to make these payments, which typically amounted to two gulden per person. Since, with few exceptions, these were instrumental musicians, the payments are most plausibly explained as compensation for performances at typical events such as entries, celebrations, or dance events, either alongside the city’s own pipers, or instead of them.[86]

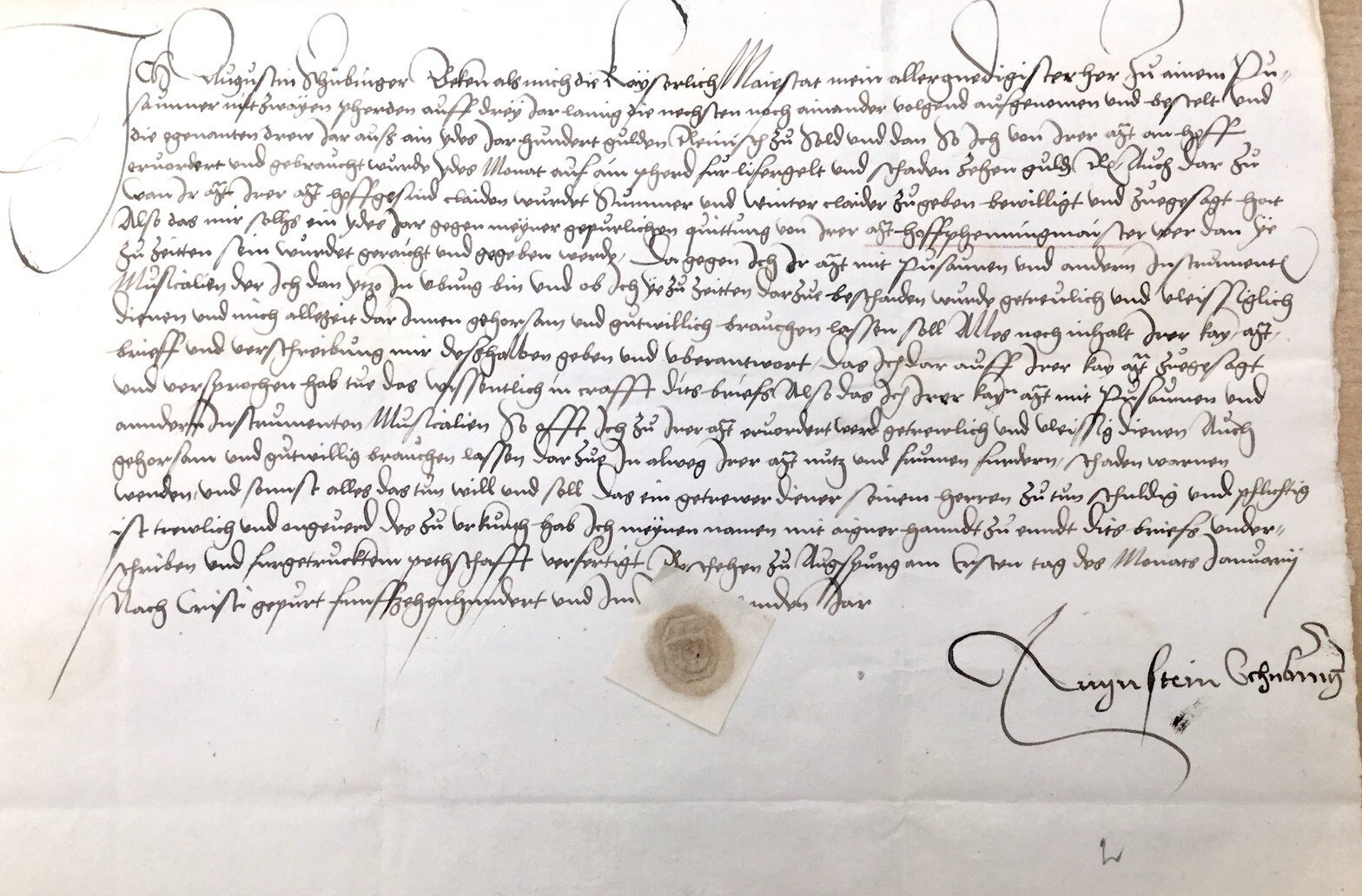

Schubinger’s Appointment in 1514

Documents from the year 1514 provide a closer look at the terms of Schubinger’s employment at Maximilian’s court. The letter of appointment is dated January 1 1514 and covers the next three years.[87] The corresponding contract of service is personally signed by Schubinger:

Fixed-term appointments, which could indeed accumulate to long-term employment relationships, were not uncommon at Maximilian’s court. For example, the trombonist Hans Steudl, who served Maximilian for many years,[88] was reappointed on January 1, 1514, for three years, just like Schubinger.[89] The composition of the remuneration was also typical, consisting of a salary, expenses for the maintenance of a horse, at a rate of 10 florins per horse,[90] and an allowance for livery. Due to the high prices of textiles, the allowance for livery significantly boosted the income. For instance, in July 1531, after his retirement, (» Ch. The Provision Letter of 1523 and the Last Years) Schubinger received an allocation of 13 gulden, 30 kreuzers, and twelve pfennigs for clothing, roughly one and a half times his active monthly salary.

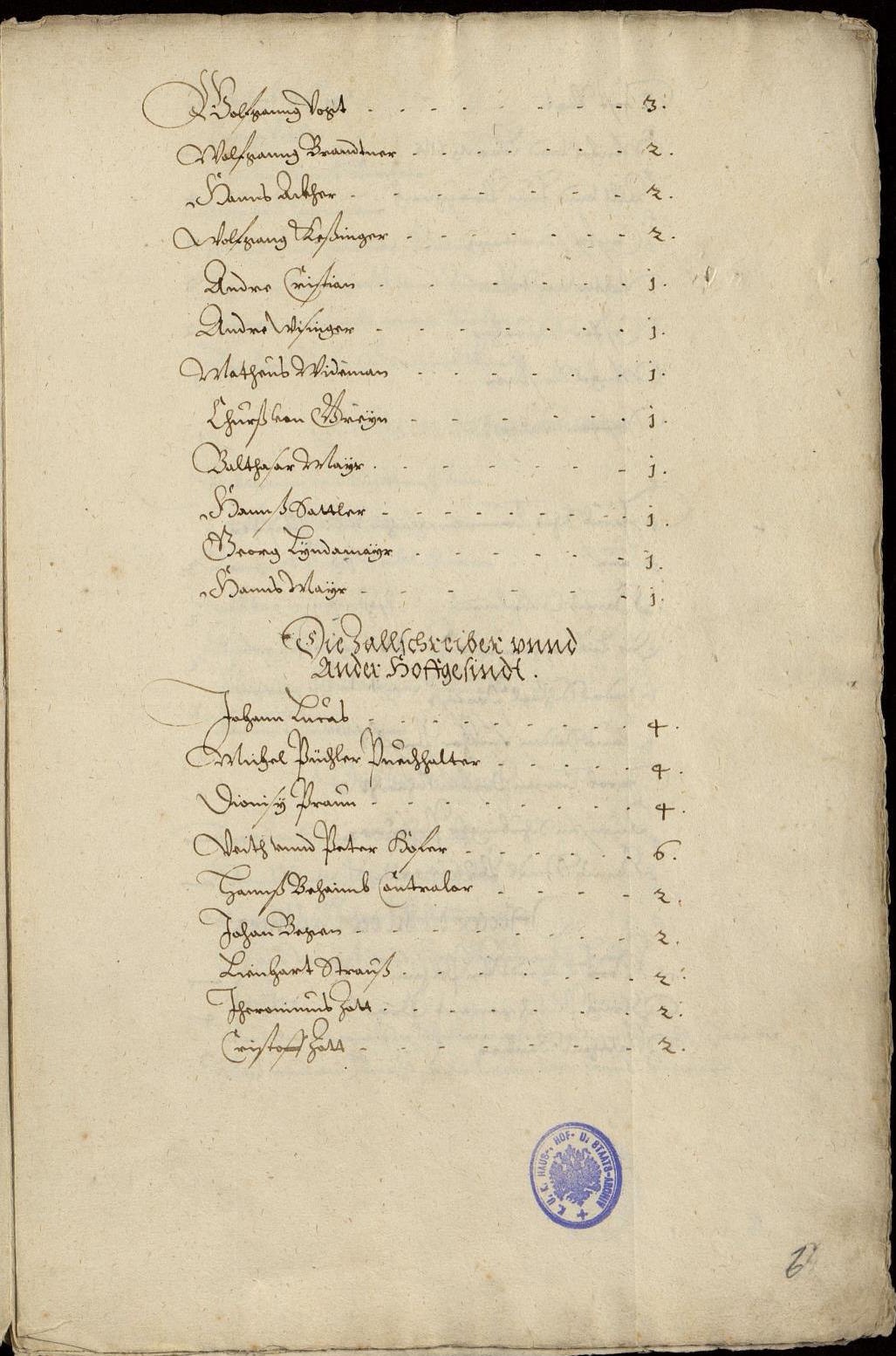

Schubinger in the Court Personnel List of 1519

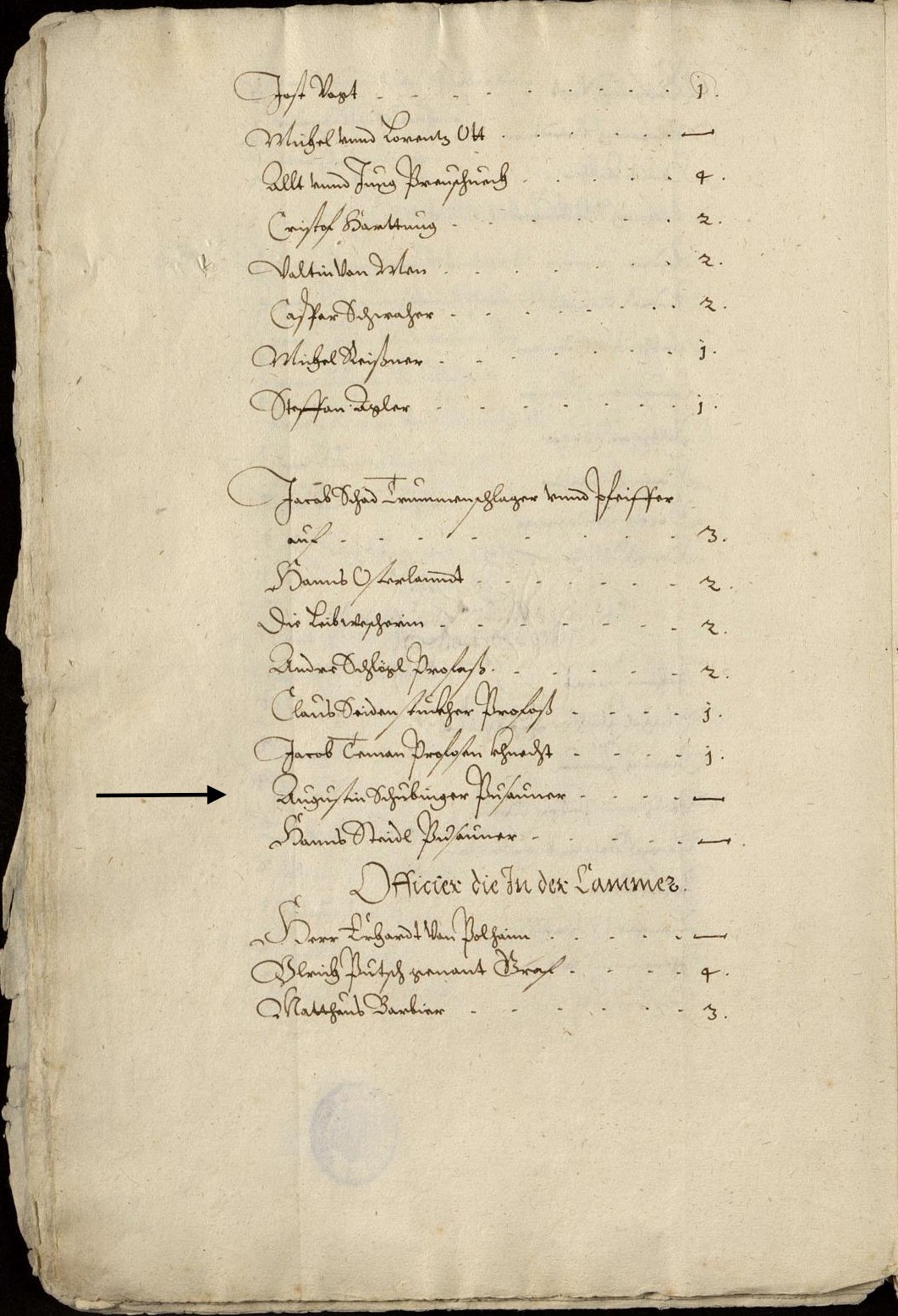

In sources from Maximilian’s court, Schubinger is mentioned for the last time in a list of the court personnel that was created in January 1519, immediately after the emperor’s death in Wels. Here, he appears – once again along with the trombonist Hans Steudl – under the category “zallschreiber vnd ander hoffgesind” (clerks and other court servants):

The fact that Schubinger and Steudl are listed at the end of this category (see arrow on the second page) can be explained by the absence of a number indicating the horses assigned to them or the delivery money to be paid for them. Nicole Schwindt inferred from this that Steudl and Schubinger simply did not have their own horses and travelled “wie im virtuellen Triumphzug […] auch im wirklichen Leben mit dem Kapellwagen” (in real life with the chapel wagon, as in the virtual Triumphzug).[91] However, this blanket conclusion is questionable. As the aforementioned employment documents from 1514 show, Schubinger was entitled to money for a horse at that time (and Steudl even for two horses). Moreover, the court personnel list from 1519 reveals that many higher-ranking and high-ranking servants were also not granted horses,[92] as were the “Personen so zu Innsprugg sein” (persons in Innsbruck) listed separately in the second part of the directory (with the exception of the falconers). This suggests that the 1519 personnel list does not reflect the fundamental contractual entitlement to horses or delivery money but only made a provision for the current situation and possibly only granted horse allowances to those court members who still had some travel activity, such as from their current location to one of the typical “home bases” of the court, such as Innsbruck or Augsburg.

More significant, however, is the classification of Schubinger and Steudl under “ander hofgesind” (other court servants). This presumably reflects the recurring problem throughout the sixteenth century of how to classify players of cornetts, trombones, and string instruments within the traditional court organisational scheme. Traditionally, the court music organisation units included (only) the chapel on one side and the trumpet corps on the other. Although cornettists and trombonists probably collaborated with the chapel in practice, they did not quite fit the institution “chapel” in the traditional sense of an association of clerics and singers. On the other hand, while they shared with the trumpeters the characteristic of being instrumentalists, they were also active in the field of polyphonic “art music” and thus musically, socially, and functionally represented a different sphere than the paramilitary corps of field or natural trumpeters. It is symptomatic of this “intermediate status” in the sixteenth century that cornettists, trombonists, and string players were sometimes listed with the trumpeters, sometimes with the chapel, or (like Schubinger and Steudl in 1519) in separate categories in the Habsburg court personnel lists.[93]

1519–1523: Ferdinand I.

From 1519 to 1522, Schubinger enjoyed the ‚usual‘ allowance of two guilders from the city of Augsburg for four years.[94] It seems likely that he initially stayed in his hometown after the death of Maximilian I., as many former servants of the Emperor, including some musicians, temporarily settled there from January 1519, waiting until Maximilian’s successor, Charles V, wished to employ them, or whether they needed to look for new job opportunities.[95]

For the approximately sixty-year-old Schubinger, the death of Maximilian I did not herald the end of his active career and permanent retreat to Augsburg. Instead, he entered the employment of Ferdinand I, the grandson of Maximilian, born in 1503. Ferdinand spent the years from 1518 to 1521 at the court of his aunt, Margaret of Austria, in the Low Countries. Following an agreement with his brother Charles V to divide the Habsburg territories between them, Ferdinand took over the rule of the Austrian hereditary lands in 1521/22. A letter of provision, with which Ferdinand I granted Schubinger an annual pension in 1523, speaks of the services the musician had rendered to the Archduke (» Ch. The Provision Letter of 1523 and the Last Years). Additionally, a record in the account book of Mechelen, the residence of Margaret of Austria, from 1520 probably refers to Schubinger. Under the section “van den officiers van don Fernando,” payments to several members of the Archduke’s household are listed, including trumpeters and a “tamboryn” as well as “Meester augustijn vuyt duytschlant die op thuereken speelt” (“Master Augustin from Germany, who plays the horn [= cornett?]”).[96] The addition “from Germany” is probably related to the fact that almost all members of Ferdinand’s household at that time came from Burgundy and Spain, making a German origin a distinctive identifying feature. Not least, Schubinger appears in the account books of Ferdinand’s treasurer general, Gabriel von Salamanca, from the period 1522/23: » Abb. Schubinger in Gabriel von Salamancas Rechnungsbüchern 1522/23.

The mention of Schubinger in sources related to the early court of Ferdinand has further significance. Together with other references, it suggests that Ferdinand had a wind band, specifically a cornett-trombone ensemble, well before the year 1527, which has so far been considered the “actual” beginning of his court music (» I. Kontinuität und Wandel, Kap. Ferdinands und Annas Zink-Posaunen-Ensemble).

The Provision Letter of 1523 and the Last Years

Habsburg rulers customarily supported long-serving members of the court in old age or after the end of their active service through a “provision” or pension. Schubinger too received such a pension in 1523. This provided him with a lifelong pension of 40 gulden annually, and simultaneously released him from all service obligations to the House of Habsburg.

Schubinger’s Provision Letter of 1523

Maister Augustin Schubinger / pusawner / xl gulding rh provison / Wir Ferdinand von gots gnaden prinz und infant in his-/panien Erzherzog zu österreich, herzog zu Burgundi / Steyr, kerndten und Crain & Grave zu Tirol & / Bekennen für uns und unser erben offennlich / mit diesem brief, daz wir unnseren getreuen maister / Augustin Schubinger pusawner, umb seiner getreuen / vleissigen diennste willen so er weiland unnseren / lieben herren und anherren kaiser maximilian hoch- [fol. 76v] loblichen gedechtnius, lannge zeit an Irer mt hof und / nachmals unnseres lieben herrn und brueder / kaiser karlen und unns, bis auf heut dato be-/wissen, unnd getan hat, zu ergezlichait aller der-/selben seiner dienste und annordnungen nichts / ausgenommen, so er zu gedachten unnseren lieben / herrn und brueder, und unns zuhaben vermainit, / zu seiner fursehung vierzigk guldin Reinisch / järlicher provison sein lebenlanng von den ein-/komen und gevellen der tirolischen camer / geordnet, unnd verschrieben haben, thun das auch / wissentlich hirmit in crafft dies brieffs, alß, daz er uns hinfür solch virzighte guldin Reinisch / provision, von bemelter tirolischer camer haben, / die ime auch järlich sein lebenlanng, durch / unsere gegenwirtig unnd künfftig raiträte dere ober-/österreichischen land von den einkommen / der selben unnser tirolischen camer, gegen seinen / quittungen, zu halben jarszeiten, geraicht unnd / bezalt, Und mit der ersten bezalung / von heut dato über ain halb jahr dem negsten / angefanngen werden, innhalt unns sonderen / bevelchs auf dieselben RaitRäte deshalben von / unns ausgegangen, Doch soll er wider bemelten / unnsern lieben herrn und Brueder kaiser karlen / unns unnd unnser haus österreich niemands weiter / wer der sey / nit dienen, sonder sich in allweg halten [fol. 77r] als ainen getreuen diener und provisioner geburt und zuesteet, alles treulich unnd ungeverlich, mit / urkundt dis brieffs, Geben zu Innsprugg / am ersten tag des monats Augusti, Nach Cristi / unnseres lieben herren gepurde, fünffzehnhundert / unnd ins dreyunndzwainzigistes jahres, / durch f.d. Rabenhaupt, unnd Rhta v. Waldenburger underschriben.

A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Kopialbücher, Geschäft von Hof, Bd. 87 (1523), fol. 76r-77r.

Whether the mention of Charles V as Schubinger’s employer was merely ‚pro forma‘, due to Charles’s position as head of the dynasty at the time, or whether Schubinger actually worked for Charles, cannot be determined. He might have had the opportunity to serve at events such as the king’s coronation in Aachen in 1520 or the Imperial Diet in Worms in 1521, but there is no evidence of Schubinger’s presence at these events.

If the payments of Schubinger’s provision were fully recorded in the Raitbücher (payment records) of the Innsbruck Treasury,[97] which can generally be assumed,[98] he, like many court servants, fell victim to the notoriously poor payment practices of the Habsburg rulers, as the annual payments to him were mostly well below the promised 40 guilders.[99]

Aside from his age, several factors suggest that the now elderly Schubinger, probably in his seventies, returned to his home town after 1523. He – and not just his wife – reappears in the Augsburg tax records,[100] and received annual payments from the city treasury from 1527 to 1531.[101] The payments from the Innsbruck Treasury were received on his behalf by his brother Ulrich or Marx Perner, a former trumpeter of Maximilian I:[102]

Augustin Schubinger Pusauner inabslag / seiner provison, zuhanden seines brudern / Ulrichen Schubinger Pusauner zu Salzburg / laut bevelch und quittung datum am xj tag octobris Anno xxiiij / xiij gulden (Augustin Schubinger, trombonist in compensation of his provision, to be handed to his brother Ulrich Schubinger, trombonist in Salzburg, according to order and receipt dated 11 October, year 1524 / 13 gulden).[103]

The Raitbücher of the Innsbruck Treasury record several payments to Schubinger from May to July 1531 “in Abschlag seiner Provision” (in deduction of his provision), with the explicit addition in May, “inansehung das er in schwerer krankhait vnd todtsnöten ligt” (in view of his severe illness and imminent death). These are the last (currently known) documents related to this key representative of instrumental music around 1500.

[1] A-Wn Cod. 2835 („Was in diesem püech geschriben ist, das hat kaiser Maximilian im xvc und xii Iar mir Marxen Treytzsaurwein seiner kay. Mt. secretarÿ müntlichen angeben.“), fol. 9r; Digital copy: https://digital.onb.ac.at/RepViewer/viewer.faces?doc=DTL_2985406&order=1…. Edition: Schestag 1883, 160.

[2] See Lütteken 2011, 174–181; Heidrich 2004, 58–63; » I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I (Martin Kirnbauer).

[3] Initial insights into the biographies of the members of the Schubinger family are mainly owed to Keith Polk. See especially Polk 1989a (with numerous source references); Polk 1989b.

[4] See e.g., D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 55 (1457), fol. 112v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-03uw/1), vol. 56 (1458), fol. 120v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-0436/1), vol. 57 (1459), fol. 122v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-04cw/1).

[5] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 45 (1447), fol. 82r–82v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-06yu/1); cf. also Polk 1992a, 237.

[6] Generally on the institution of urban wind ensembles in late medieval Germany, see Polk 1987; Polk 1992a, 108–114; Green 2005; Green 2011; Neumeier 2015, 143–172; specifically on Augsburg, see Green 2012. These studies will be expanded here in » E. Musiker in der Stadt to cities of the Austrian Region.

[8] Polk 1989a, 498, note 1; Polk 1989b, 90, note 6; Polk 1987, 179.

[9] Moreover, the Augsburg accounting books from 1521 record a trumpeter named Jörg Schubinger in the service of Cardinal Matthäus Lang; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 115 (1521), fol. 32v (“Item i guldin Jorigen Schubinger des Bischoffs von Saltzburg trumetter”), see Birkendorf 1994, vol. 3, 247. Further details, particularly the family relationship to other Schubingers, about this musician are currently unknown.

[11] Polk 1989a, 495, speculates, with a view to the later careers of his sons, about a stay in Italy, which is not documented.

[12] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 70 (1477), fol. 92v.

[13] Green 2005, 22–23.

[14] D-Asa Ratsbücher, vol. 10 (1482–1484), fol. 124r; see Green 2005, 23.

[15] The entries in the Augsburg accounting books that record Schubinger as a town piper are: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 74 (1481), fol. 64v; vol. 75 (1482), fol. 62v; vol. 76 (1483), fol. 53v; vol. 77 (1484), fol. 60r; vol. 78 (1485), fol. 52v; Ratsprotokolle vol. 10 (1484), fol. 124r; Baumeisterbücher, vol. 79 (1486), fol. 62r; vol. 80 (1487), fol. 65r. (The accounting books from the years 1478 to 1481 have not survived).

[16] For example, at the end of Maximilian I’s reign, the trumpet corps included Ludwig (Lutz) Mayer (Mair) and his sons Georg (Jurig) and Christoph. See the court personnel list of 1519 in Fellner/Kretschmayr 1907, 141, as well as Senn 1954, 20 and 22; Wessely 1956, 104–106. On Vienna musician families, see » E. Instrumentalisten und ihre Kunden. Cf. also the detailed reconstruction of family relationships within the urban instrumental ensembles of Florence in McGee 1999, 732–736.

[17] Schubinger, whose annual salary (totaling 36 fl.) was paid in four tranches on Ember Days, received his last payment on March 31, 1487, proportionally for the three-week period between Ember Day before Reminiscere (March 7) and the end of the month; see D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 80 [1487], fol. 65r: “Augustin Schubinger busauner […] Rt. ij v ß für 3 wochen antzal der quattember vnd ist daruff abgeschiden zu vnnserm Herren dem Ro. Kaÿser vnd vff seiner Kayserlichen gnaden schreiben seins dinsts erlassen. Samstag vor Iudica [March 31].” In 1488, Schubinger is already documented as “Emperor’s Trombonist” in the Augsburg accounting books, under the category “varende levte” where payments to outsiders were recorded; see Baumeisterbücher, vol. 81 [1488], fol. 16r: “Item ij fl Augustin kayserlicher busaner Samstag vor Reminiscere.” Polk 1989a, 501, mistakenly refers to “Emperor” as Maximilian I, who was not crowned Roman-German Emperor until 1508.

[18] Among others, D-Asa Steuerbuch 1504, fol. 17v (category d); Baumeisterbücher, vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v; vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28v. The identity of this “Augustin pfeiffer” with Schubinger is shown in the following entry concerning Schubinger’s wife in the tax book 1509, fol. 16r (category a): “magdalena schubingerin Augustein pfeiffers weib”.

[19] See Wessely 1958, 94; McDonald 2021, 177–178; » I. The court chapel of Maximilian I. (Grantley McDonald), Kap. Finances.

[20] Wessely 1958, 174, according to: Finance and Court Treasury Archives Vienna, Lower Austrian Treasury, files 14, no. 113.

[21] Cf. on the now well-documented instrumental music in Florence of the fifteenth century: Zippel 1892; Polk 1986; McGee 1999; McGee 2000; Polk 2000; McGee 2005; McGee 2008.

[22] McGee 2008, 185–186, 202.

[23] McGee 1999, 730–731; McGee 2000, 212–213.

[24] Cf. general literature on the alta cappella: Polk 1975; Welker 1983; Polk 1992a, 60–70, estimating that around 100 cities and 150 princes in the Holy Roman Empire employed an alta cappella (68); Tröster 2001; Neumeier 2015, especially 46–54. On practice in the Austrian region, see » E. Kap. Repräsentation und Unterhaltung; » I. Kap. Musica, Schalmeyen.

[25] The exact origin of musicians from “Alemania” is often not determinable. According to contemporary Italian usage, “Alemania” included the entire territory of the Holy Roman Empire, including regions like Flanders and Alsace. See Böninger 2006, 9–10.

[26] Cf. especially Polk 1994a.

[27] Lockwood 1984, 321–326; Lockwood 1985, 110 and 112, who also identified a son of Michel named Alberto (Albrecht), documented as a piffaro at the court of Ferrara in 1510/11 and 1517–1520.

[28] Ulrich is last documented in Mantua in October 1519; see Prizer 1981, 160. Contrary to the speculation that he may have remained in Mantua until 1522 (Polk 1989a, 502; Filocamo 2009, 235, note 17), it should be noted that Ulrich was employed by Archbishop Matthäus Lang in Salzburg in December 1519; see the service agreement (“Abred”) text in Hintermaier 1993, 38; see previously the note in Senn 1954, 21.

[29] Lockwood 1984, 190.

[30] McGee 1999, 732; McGee 2008, 162–163.

[31] D’Accone 1993; Zavanello 2005, 35–45.

[32] McGee 1999, 740–743; see also McGee 2005, 145–149; McGee 2008, 178–189.

[33] See the letter from Bartolomeo Tromboncino to Lorenzo de’ Medici dated June 10, 1489; edited in: Becherini 1941, 108–109.

[34] Letter from Michel Schubinger to Lorenzo de’ Medici dated June 7, 1489, in: Becherini 1941, 107–108. See also McGee 2008, 185–186. The stay in Milan may have been related to the wedding of Gian Galeazzo Maria Sforza and Isabella of Aragon on February 2. Details are unknown. It is certain, however, that Schubinger was not in the entourage of Friedrich III, who was in the Netherlands at that time.

[35] This document was first highlighted by Böninger 2006, 127. An in-depth analysis of the historical implications can be found in Schwindt/Zanovello 2019.

[36] About Cornelio di Lorenzo: D’Accone 1961, 334, 337, and 341–343.

[37] Schwindt/Zanovello 2019. See also Schwindt 2018c, 259–260.

[39] D-Asa, Baumeisterbücher, vol. 89 (1495), fol. 17r: “Augustin Schubinger der K Mt Trumbetter.” Senn 1954, 21, mentions (but without further source reference) an “apparently temporary” presence of Schubinger in Innsbruck in 1493.

[40] A 1495/96 payment by the city of Basel to “des romischen konigs zinken bloser” may also refer to Schubinger. See Ernst 1945, 222; Polk 1989b, 88.

[41] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 255–256; Schwindt 2018c, 94–95.

[42] Payment record January 1497, F-Lad B 2159, fol. 178r–178v.

[43] Haggh 1988, 219; Polk 1992b, 88.

[44] Appointment document March 10, 1497, F-Lad B 2160, No. 71187. My heartfelt thanks to Grantley McDonald for bringing this and the document mentioned in note 43 to my attention.

[45] Bessey et al (Eds.) 2019, 192.

[46] Bessey et al. (Eds.) 2019, 23–24. I thank Werner Paravicini for relevant information (email, February 4, 2022).

[48] Unless otherwise mentioned, the information about Maximilian’s whereabouts here and in the following is based on Regesta Imperii XIV (online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/regesten/baende.html), Stälin 1860 sowie Kraus 1899.

[49] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v. The payment note concerning Schubinger is not dated, but the preceding and following notes are, respectively, “Samstag vor katharina,” i.e., November 24, and “Samstag post lucie,” i.e., December 15.

[50] Wessely 1956, 115.

[51] RI XIV,3,1 n. 9792, in: Regesta Imperii Online, http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1500-01-30_4_0_14_3_1_814_9792. See the text of the letter in: Bertolotti 1890, 25. Based on this letter, the literature sometimes claims that Schubinger was in Mantua in January 1500; see Polk 1989a, 502; Filocamo 2009, 238. According to Filocamo, Schubinger is also mentioned in the spring of 1505 in the correspondence between Isabella and Alfonso d’Este. This possibly forms the basis of Polk 1989a, 501, unsubstantiated statement that Schubinger was active in Mantua in 1505. Definitive clarification will only be possible after an autopsy of the letters, which has yet to be undertaken.

[52] Wessely 1956, 116; Luger 2020, 118 and 136.

[53] Wessely 1956, 101–102.

[54] Schubinger, Jobst, and Jörg Nagel, as well as Jörg Holland, also received a payment from the city; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 99 (1505), fol. 27v–28; see Polk 1992b, 86.

[55] As suspected by Kelber 2018, 48, note 90.

[56] In: Hegel (Ed.) 1894, 83. See also Kelber 2018, 115.

[57] Schweiger 1931/32, 367.

[58] Straeten 1885, 172.

[59] Further payments from the Burgundian court to Schubinger are documented in: F-LadB B 2173 (Registres de comptes de la recette générale des finances 1501), fol. 73r–v; B 2180 (1502), fol. 154r and 186r (see van Doorslaer 1934, 39, and 163); B 2191 (1505), fol. 318r (see Fiala 2002, 379).

[60] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41281 (Stadsrekeningen Mechelen 1500/1501), fol. 192v: Payment to “Meester Augustyn diener ons genedige Herrn Hertoge Phillips van dat hij op ons liever vrouwen lichtmes dach speelde te hoogmissen In Sinte Rombouts kerke.” See also Polk 2005a, 65

[61] Gachard (Ed.) 1876, 178 and 287. See also Straeten 1885 1885, 158, and Polk 1989a, 501, who mistakenly identify Lausanne instead of Bourg-en-Bresse as the location of the Easter 1503 service.

[62] See van Doorslaer 1934, 51; Straeten 1885, 162–165; Pietzsch 1963, 746; Haggh 1980, 172–176; Ferer 2012, 33.

[63] Bessey et al. (Eds.) 2019, 350 and 355.

[64] It is also possible that Schubinger was the “des Ro. Ko zincken plaser” (imperial cornett player) documented in Nuremberg in 1506. See D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 407v: “Item i gulden des Ro. Ko zincken plaser”.

[65] Cf. Schwindt Schwindt 2018c, especially 53–56.

[66] Stadtarchiv Nördlingen, Stadtkammerrechnungen 1507, fol. 60v: “Augustain Zinkenblasser Kl. Mayt. busawnner verert selbannd auff aftermontag nach sanct vallentainstag [19. Februar]”; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 101 (1507), fol 24r: “Samstag nach Letare [20. März]. […] Item ij guldin Augustin Kö mayt Busaner.” Also in 1507 is a likely reference to Schubinger, though not precisely dated, in: D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 426v: “Item i gulden der Romischen Kaiserlichen mt zinckenplaser.”

[67] See the detailed references in Kelber 2018 LIT, 58–59, 142; Grassl 2019, 239.

[68] Cf. the comprehensive account of this partly immensely agile and stimulating, partly quiet and productive period of music in Maximilian’s orbit in Schwindt 2018c, 188–194.

[69] Schuler 1995, 13–14 and 18–19.

[70] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 51 (word and page identical in vol. 52), fol. 239r: “Augustin schubinger pausauner geben / am xxij tag november zu seiner / außlosung hier, laut seiner quittung / iij gulden”.

[71] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mecheln 1507/1508), fol. 211r.

[73] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 58 (1512), fol. 299v (identical wording in vol. 59, fol. 139r–v): “Augustin Busaner x gulden an seinem Lifergelt.”

[74] See references in Grassl 2019, 241.

[75] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41291 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen, 1. Nov. 1511–31. Oct. 1512), fol. 209v.

[76] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 106 (1512), fol. 30v: “Samstag post katherine [27 November] / Item ij gulden dem Augustein pfeiffer Kay mt diener.”

[77] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 101 (1507), fol. 24r: “Samstag nach Letare [20 March]. […] / Item ij guldin Augustin Kö mayt Busaner”; vol. 103 (1509), fol. 24r: “Samstag post Cantate [12 May]. / Item ij guldin dem Augustein Kay mayt Busaner”; vol. 106 (1512), fol. 30v: “Samstag post Katherine [27 November] / Item ij gulden dem Augustein pfeiffer Kay mt diener”; vol. 108 (1514), fol. 26r: “Samstag nach Egidy [2 September] / Item ij guldin Augustein Busaner Kay mayt diener”; vol. 111 (1517), fol. 30r: “Samstag nach Egidij [5 September] / Item iiij guldin vlrichen vnd Augustein von augsburg busanern”; vol. 112 (1518), fol. 31r: “Samstag Leonhardj [6 November] / Item ij guldin augustein von Augsburg Kay mt. busaner.”

[78] Schwindt 2018c, 202–207.

[79] This is evident from the form of Schubinger’s entry in the Augsburg tax books, which lacks the designation typical for foreigners or non-citizens. For a detailed discussion of these sources and the Augsburg tax system of the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period: Clasen 1976 LIT; Krug 2006.

[80] D-Asa Steuerbücher 1495, fol. 14v (category c); 1501: fol. 18v (category d); 1505, fol. 17v; 1507, fol. 15r; 1508, fol. 15v (category c); 1509, fol. 16r (category a).

[81] Clasen 1976, 17–18.

[82] The claim that Schubinger was the owner of a house at Rossmarkt (so Busch-Salmen 1992, 65), cannot be verified based on the tax books.

[83] The Augsburg tax books from 1521 and 1522 mention a “Magdalena Schubingerin” with a tax payment; D-Asa tax books 1521, fol. 18v (category d), 1522, fol. 18r (category b). This person was likely not Schubinger’s wife (but perhaps his unmarried daughter?), because wives were usually recorded with their husband’s surname preceded by their first name and followed by the suffix “in” or with a reference to their marital status (e.g., in 1509, Schubinger’s wife: “magdalena schubingerin Augstein pfeiffers weib”). See Clasen 1976, 19.

[84] For Hofhaimer’s tax exemption, which was not fully accepted by the city authorities, see Nedden 1932/1933, 28–29; Schuler 1995.

[85] Böhm 1998, 166–168.

[86] Schwindt 2018c, 202–203; Schwindt 2020, 63–64; Birkendorf 1994, vol. 3, 243. For municipal expenses for performances by instrumentalists, see also » E. Städtisches Musikleben.

[87] A-Whh Reichskanzlei, Reichsregisterbücher QQ (Maximilian I.: Reichs- und Hauskanzleiregistraturbuch 1514), fol. 36v–37r; online: https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=1274877&DEID=10&S….

[88] For Steudl, see Schwindt 2018a, 2–4.

[89] Appointment document: A-Whh Reichskanzlei, Reichsregisterbücher QQ (Maximilian I.: Reichs- und Hauskanzleiregistraturbuch 1514), fol. 36r–36v; service contract: A-Whh Urkundenreihe, Familienurkunden 969. For other examples of (often three-year) appointments, see RI XIV,2 n. 7032; RI XIV,3,1 n. 11552; RI XIV,3,2 n. 10718, n. 14172; RI XIV,4,1 n. 16514, n. 16810; Kostenzer 1970, 80, 82, 88 and 93; see also Gänser 1976, 30 and 185.

[90] See generally Zolger 1917, 43; Gänser 1976, 47–50; Noflatscher 2017, 425–426.

[91] Schwindt 2018a, 3; Schwindt 2018c, 53.

[92] As with the treasurer Jacob Villinger, who according to his appointment letter from 1512 was entitled to horses. See Fellner/Kretschmayr 1907, 51 and 142.

[93] See examples in Wessely 1958, 408, 410; Pass 1980, 350, 354, and 392; Grassl 2011, 120–121 and 129. For the case of the “geyger” Caspar Egker, who is listed under “Annder Officir” in the directory of Maximilian’s remaining court staff from 1520, see Koczirz 1930/1931, 531–532. For this period, see » I. Kap. Ferdinands und Annas Zink-Posaunen-Ensemble.

[94] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 113 (1519), fol. 30r: “am hailigen pfingstabent [12 June] / Item ij gulden Augstein Schubinger Kay mayt hochloblicher gedachtnis Busaner gewesen ist”; vol. 114 (1520), fol. 32r: “Samstag nach Letare [24 March] / Item ij guldin Augustein Schubinger weyland Kay trumeter”; vol. 115 (1520), fol. 32v: “Samstag post Johannes Baptiste [29 June] / Item ij gulden Augustein Schübingern Kay mayt. busaner”; vol. 116 (1522), fol. 35v: “Samstag post Udalricj [5 July] / Item ij guldin. Augustein Schubinger Kay. mt busawner”.

[95] See Schwindt 2018a, 14; Schwindt 2018c, 207; Bente 1968, 293–294.

[96] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41298 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen, 1. Nov. 1519–31. Okt. 1520), fol. 232v. For the meaning of “thuereken” as cornett, see Polk 1992b, 88, who cites the reference not in connection with Ferdinand, but with “musicians in the retinue of Maximilian I.” Historians have also overlooked the Mechelen city accounts as a source for reconstructing Ferdinand’s court during his time in the Netherlands; see Castrillo-Benito 1979, 426–427; Rill 2003, 37–46.

[97] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 73 (1524), fol. 194v; vol. 74 (1525), fol. 157v; vol. 75 (1526), fol. 147v (1527 missing); vol. 76 (1528), fol. 140v; vol. 77 (1529), fol. 167v; vol. 78 (1530), fol. 178r–v; vol. 79 (1531), fol. 170r–171r.

[99] Payments ranged from 1524 to 1529 between four and 13 gulden; only in 1530 and 1531 did the Innsbruck Treasury allocate 89 and 48 gulden, 31 kreuzers, and three vierers (partly not in cash but by covering clothing costs), but even then, the total amount due over the years was far from reached.

[100] Once again without an amount specified; D-Asa tax book 1528, fol. 23v (category c); tax book 1529, fol. 23r (category b).

[101] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher vol. 121 (1527), fol. 36r: “Samstag nach trinitatis / Item ij fl. Augustein Schubinger k. mt. pusauner”; vol. 122 (1528), fol. 36v: “Samstag nach margrethe / Item ij fl augustein schubinger verert”; vol. 124 (1530), fol. 35r: “Samstag nach Reminiscere / Item ij guldin Augustein Schubinger”; vol. 125 (1531), fol. 36r: “Uff 5. Januarij / Item ij gulden Augustein Schubinger”.

[103] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 73 (1524), fol. 194v.