Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.

Hofmusik und Repräsentation

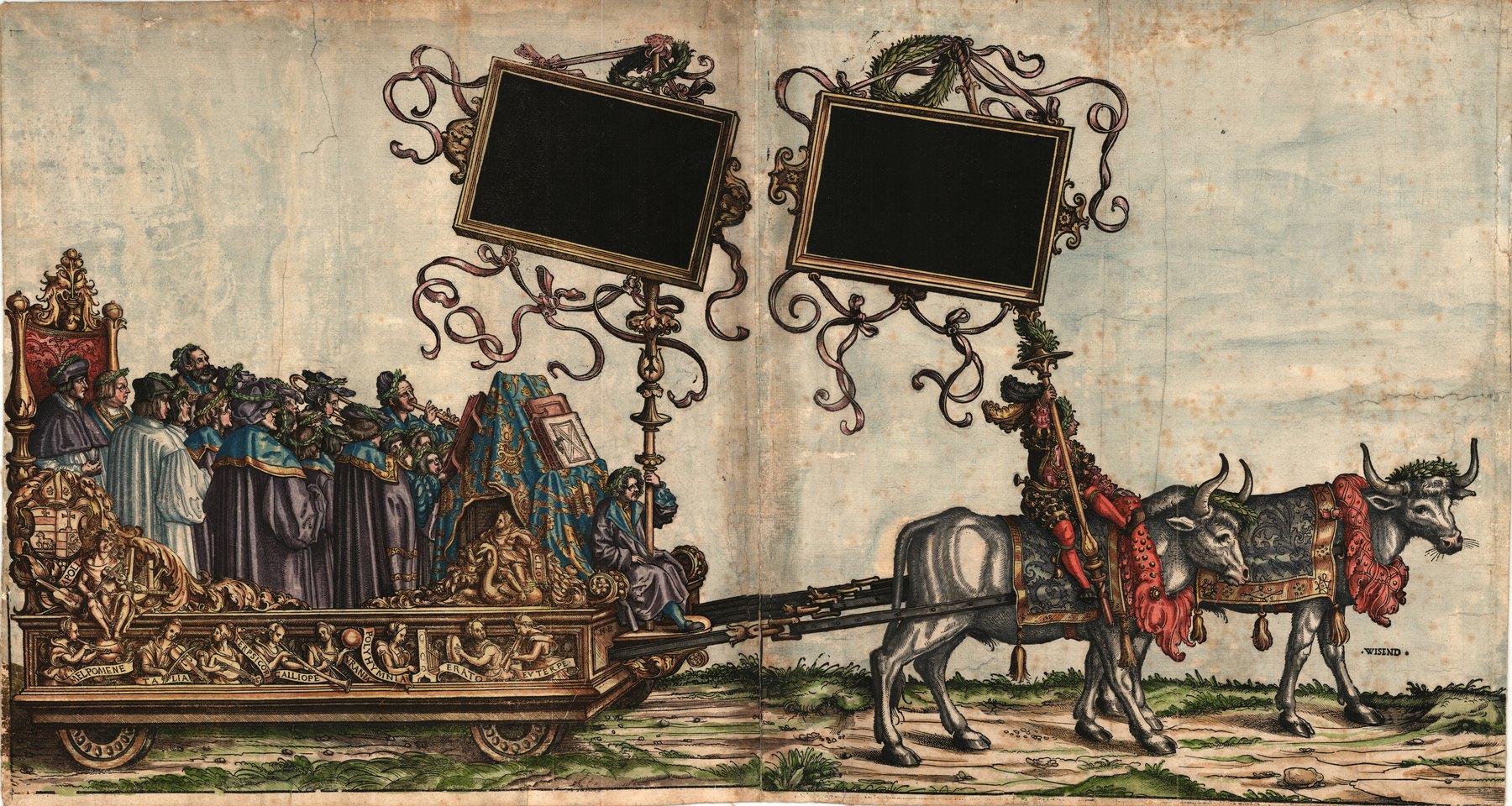

Der Reichtum und Umfang des musikalischen Repräsentationsapparates von Kaiser Maximilian I. (1459–1519) wird anschaulich in den Holzschnitten des sogenannten Triumphzugs – allerdings sollte dabei nicht vergessen werden, dass es sich bei diesem ebenso ambitiösen wie kostspieligen Bilderprojekt nicht um eine realistische Darstellung seiner Hofkapelle handelt, sondern um ein stark idealisiertes Wunschbild „zu lob vnnd Ewiger gedächtnüs“ des um seine Reputation besorgten Monarchen.[1] In dem in zusammengesetztem Zustand wohl über 100 Meter langen Bilderfries finden sich neben dem Wagen mit der eigentlichen Hofkapelle (betitelt „Musica Canterey“ mit dem Kapellmeister Georg Slatkonia und Sängern) noch vier weitere Musikerwagen, nicht zu vergessen die stattliche Anzahl der im Zug vertretenen Trompeter und Pauker, „Burgundisch pfeyffer“ sowie Pfeifer und Trommler. Die viel bescheidenere historische Realität des maximilianischen Musikapparates bildet sich hingegen in den Rechnungsbüchern ab, etwa in dem Verzeichnis anlässlich der Auflösung der Hofkapelle 1520 nach dem Tod Maximilians: Hier figurieren insgesamt 13 „Trumetter vnd paugker“, 19 Sänger und etwa 20 Knaben als „Discantisten“ sowie ein „organista“ in der „Capellen oder Cannthorey“; unter den übrigen Chargen wird schließlich nur noch ein „geyger“ aufgeführt.[2] Diese Diskrepanz erklärt sich aus den unterschiedlichen Funktionen der Musiker: Die Sänger wurden für die Gottesdienste benötigt, die Trompeter und Pauker waren in erster Linie ein optisch-akustisches heraldisches Zeichen und stellten als die vielzitierte „Ehr und Zier“ ein unverzichtbares Statussymbol des Herrschers dar.[3] Die übrigen Musiker hingegen dienten vor allem der sogenannten „Kurzweil“ und wirkten nur indirekt repräsentativ, etwa bei Reichstagen oder als musikalische Botschafter, wenn sie, gekleidet in den Farben des Herrschers, beispielsweise als des „zwayen siner Maiestat Luttenschlager“ in den Reichsstädten und bei Fürstenhöfen auftraten und dafür stattliche Geldgeschenke erhielten.[4] Venezianische Gesandte, die Maximilian 1492 in Strassburg trafen, berichten von der Ehre, die sie durch den Besuch der königlichen Musiker in ihrem Quartier erhielten: Es erschienen 14 Trompeter mit großen Pauken, aber auch Pfeifer, Trommler und Lautenspieler. Weiter drei Brüder mit ihrem Vater, die ein Claviorganum (ein Tasteninstrument, dass Orgel und Cembalo kombiniert), Laute und Fiedel spielten.[5] Auch dieses kunstreiche Familienunternehmen wird ausdrücklich als zum Hofstaat gehörig bezeichnet, obwohl sie archivalisch bislang dort nicht dokumentiert werden konnten.

Wohl vor allem die repräsentative Funktion – mehr noch als sein eigenes musikalisches Bedürfnis – erklärt das Interesse Maximilians, herausragende Instrumentalmusiker mit seinem Hof zu verbinden. Bekanntlich galten die Musik und die Musiker an einem Hof als wichtiger Bestandteil des Herrscherruhms.[6] In diesem Sinne sind auch die Berichte über Maximilians besondere Liebe zur Musik als Teil eines Herrscherlobs zu verstehen, wie dies etwa in der Biographie seines humanistisch geschulten Leibarztes Johannes Cuspinianus zu lesen ist:

„Musices vero singularis amator, quod vel hinc maxime patet, quod nostra aetate musicorum principes omnes in omni genere musices omnibusque instrumentis in ejus curia veluti in fertilissimo agro succreverint, veluti fungi unâ pluviâ nascuntur.“[7]

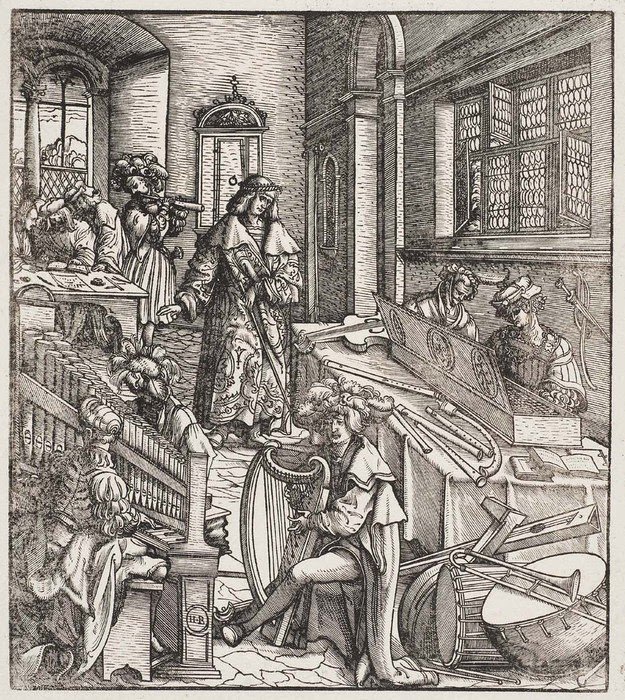

(Er war ein einzigartiger Musikliebhaber, was schon daraus deutlich hervorgeht, daß alle großen Meister der Tonkunst unserer Zeit in jeder Musikgattung und auf allen Instrumenten an seinem Hof sich wie auf fruchtbarsten Acker entfalteten wie Pilze, die nach nur einem Regenschauer wachsen.)Ganz ähnlich zu verstehen ist die oft zitierte Passage im Epos Weißkunig, ein dem Triumphzug vergleichbares ambitiöses Publikationsprojekt Maximilians. Hier wird berichtet, wie der junge König, ein idealisierter Alter ego Maximilians, eine „Canterey“ einrichtet, „mit ainem sölichen lieblichn gesang, von der menschen stymm wunderlich zu hören, vnd söliche liebliche herpfen, von Newen wercken, vnd mit suessem saydtenspil, das Er alle kunig übertraff, vnd Ime nyemandts geleichen mocht, sölichs unnderhielt Er, fur vnd fur, das ainem grossen furstenhof geleichet, […]“ (mit einem lieblichen Gesang menschlicher Stimmen, die wunderlich zu hören sind, und lieblich klingenden Harfen, und neuen Instrumenten, und mit süssem Saitenspiel, dass er damit alle Könige übertraf und ihm niemand hierin vergleichbar war. Und eine solche Musik unterhielt er andauernd, wie es einem grossen Fürstenhof gebührt).[8] Auf der dazugehörigen Abbildung sieht man den Weißkunig inmitten von Instrumentalmusikern, denen er mit einem langen Stab buchstäblich den „Takt“ angibt (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33).[9] Anders gelesen zeigt die Abbildung, dass alle Musik am Hofe auf sein eigentliches Zentrum, den Herrscher, zurückgeht und -verweist.

Die Musiker am Hof Maximilians I.

Betrachtet man die lange Liste der in Rechnungsbüchern Maximilians aufgeführten Instrumentalmusiker – darunter übrigens auch eine Musikerin, „Lucia Torerin Lauttenslagerin“, wenn diese auch keine fixe Charge bekleidete –,[10] so stellen die Trompeter und Pauker (die ja ein zusammengehöriges Ensemble bildeten) die zahlenmässig stärkste Gruppe dar (» H. Zugtrompete), gefolgt von Posaunisten (» H. Posaune) sowie Pfeifern und Trommlern (letztere beiden wiederum ein Ensemble, das neben militärischen Aufgaben vor allem für die Begleitung von Tänzen verantwortlich war: » H. Einhandflöte und Trommel).[11] Die Posaunisten werden gelegentlich mit den Trompetern genannt, konnten aber auch mit anderen Musikern auftreten. Weiter sind mehrere Lautenisten genannt, die sowohl solistisch als auch im Ensemble agierten. Schließlich ist immer ein Organist aufgeführt, über lange Jahre ist dies Paul Hofhaimer (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » C. Musik für Tasteninstrumente und » I. Hofhaimer), der aber in der Regel mit der „Canterey“ oder „Capellen“, also den Sängern verbunden war.

Pfeifer und Trommler

In der repräsentativen Anordnung des Triumphzugs figurieren zu Beginn des Zuges „Pfeyffer vnd Trumlslager“, unter denen im schriftlichen Bildprogramm namentlich „Annthonj von Dornstet“ herausgehoben wird.[12] Neben der militärischen Funktion dieses Ensembles mit Kampf- und Marschsignalen wird in dem die Abbildung begleitenden Reim auch die „kurtzweyl“ genannt. Darunter ist hier vor allem das Aufspielen zu den Tänzen am Hof zu verstehen (»H. Einhandflöte und Trommel), wie dies in einer Vielzahl von Bildern im Freydal zu sehen ist, ein weiteres Buchprojekt Maximilians I. mit einem autobiographischen Bericht von seiner Brautfahrt zu Maria von Burgund.[13] Einen guten Eindruck von der Bedeutung dieser Musiker für Maximilian gibt ein Schreiben von 1495, in dem er dringend bittet, die wegen unbezahlter Schulden in Worms festsitzenden Musiker auszulösen und sofort nach Mailand zu senden, „dann wir tanzen hie stetige an ain Pfeifer und auf ainer Stelzen“.[14]

„Musica Lauten und Rybeben“: Lauten und Streichinstrumente

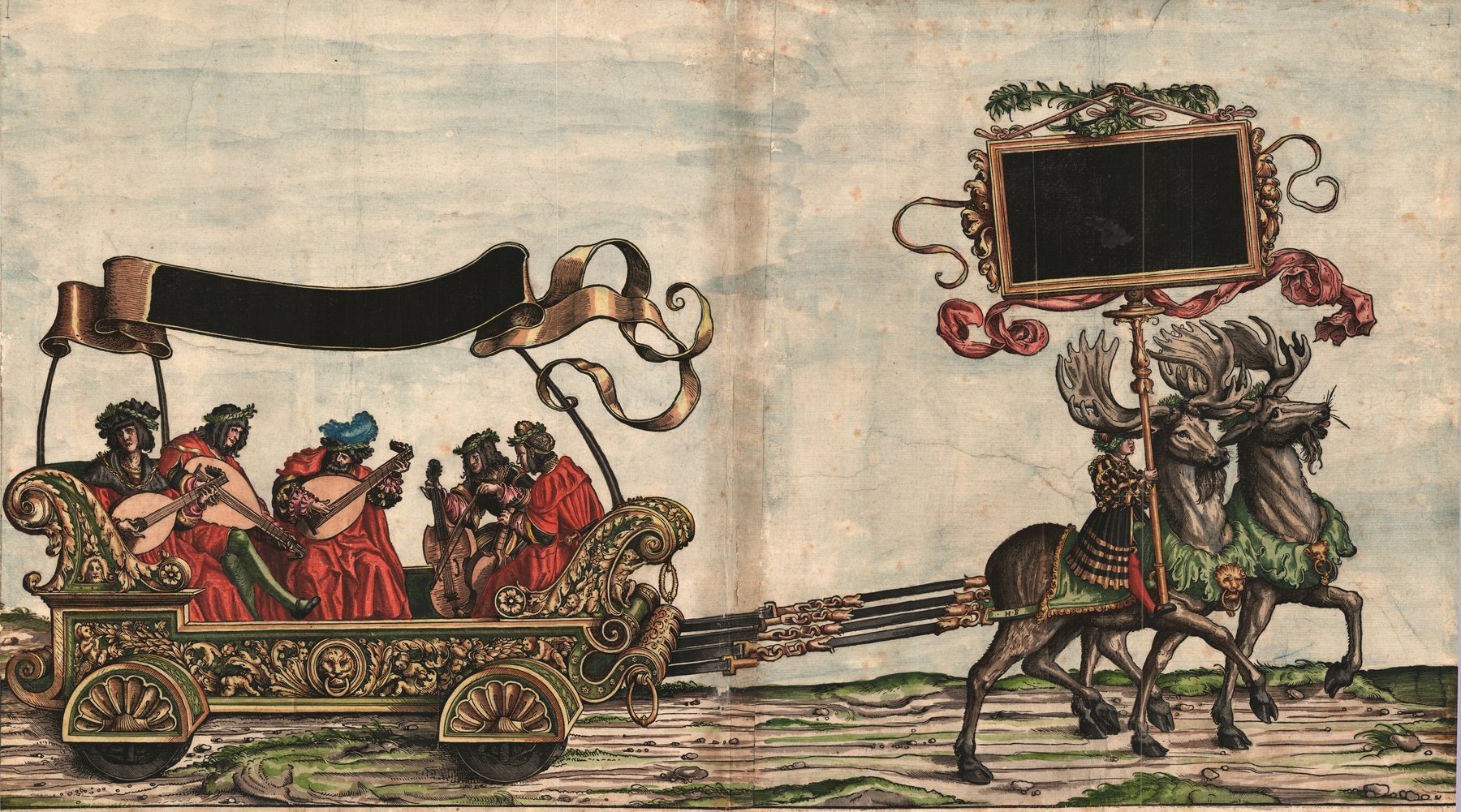

Im Triumphzug folgt etwas nach den Pfeifern und Trommlern der erste Musikerwagen, betitelt „Musica Lauten und Rybeben“ (» Abb. Triumphzug Lauten), auf dem fünf Musiker sitzen, die drei verschieden große Lauten (»H. Laute; » H. Quinterne) und zwei grössere Streichinstrumente spielen. Diese vertikal gehaltenen Instrumente können als Viole da gamba (»H.Renaissancegambe) bezeichnet werden, die Bezeichnung am maximilianischen Hof war dafür „Ribebe“. Dieser Name lässt sich von dem arabischen Rebab (rabāb) ableiten und ist bislang vor allem in Italien als Bezeichnung für ein grösseres Streichinstrument belegt. In jedem Fall handelt es sich um ein Lehnwort, das Instrument wurde also mit einer fremden Herkunft verbunden; allerdings unterscheidet es sich optisch von zeitgenössischen italienischen Darstellungen. Als „Maister“, also der hervorragendste dieser Musiker, wird ein gewisser Artus genannt, der wohl durch einen bereits älteren Mann in der Mitte des Wagens verkörpert ist. Dieser Artus hieß tatsächlich Albrecht Morhanns, firmierte aber als Artus von Enntz Wehingen.[15] Geboren um 1460 nahm er als Leibeigener an der berühmten Pilgerfahrt des Freiherrn Werner von Zimmern 1483 ins Heilige Land teil, betraut mit den Aufgaben eines Barbiers und Lautenspielers. Ausdrücklich wegen seiner besonderen Künste als Lautenist versuchte ihn Maximilian in sein Gefolge zu ziehen, so wurde er 1489 „seiner kunst schickligkeit und genediger neygung willen“ von seiner Leibeigenschaft freigesprochen. In der Folge lässt sich Artus als „des Rö. kunigs luttesschlaher“ belegen, oftmals wird er dabei mit einem zweiten Lautenisten genannt, mit dem er offenbar im Duo auftrat.[16] Ein solches Lauten-Duo ist im 15. und frühen 16. Jahrhundert gut belegt: Ein Spieler, als „tenorista“ bezeichnet, spielt den Tenor bzw. gibt ein klangliches Gerüst vor (etwa eines Liedes, einer Motette oder einer Bassedanse), während der andere Spieler, der „diskantista“, darüber improvisiert. Kennzeichen dieser Spielweise ist die Verwendung eines Plektrums, etwa ein Federkiel, mit der besonders rasche und virtuose Läufe möglich waren.[17]

Einer der jüngeren Musiker auf dem gleichen Wagen könnte Adolf Blindhamer (ca. 1480–vor 1532) darstellen, der 1503 erstmals am Hof als Lautenist belegbar ist.[18] Den Titel „lawtenslaher kays. Mt“ behielt er bis zum Tode Maximilians bei, obwohl er 1514 in Nürnberg als Bürger aufgenommen wurde, um „den Jungen auf der lauten und anndern Instrumenten“ Unterricht zu erteilen. Besonders bedeutsam ist, dass sich ein Manuskript mit Kompositionen und Einrichtungen für die Laute von Blindhamer erhalten hat, das Einblick in die konkrete Musik der Lautenisten am Hofe Maximilians bietet (vgl. Kapitel Lautenintabulierungen von Adolf Blindhamer). Hier zeigt sich eine polyphone Spielweise, bei der mehrere Stimmen zugleich mit den Fingern gezupft werden.

Die genannten „Rybeben“ wurden wohl von den gleichen Musikern gespielt, galten Laute und Gambe doch noch länger als zusammengehörige bzw. ähnliche Instrumente, wie die frühesten Lehrwerke für diese beiden Instrumente belegen (z. B. die von Hans Judenkünig, Wien 1523, oder von Hans Gerle, Nürnberg 1532) und wie es die gleichartige Einrichtung der Saiten und Bünde bzw. Stimmung auch nahelegt. Es wurde vermutet, dass die Nennung von drei bis vier „geyger“‘ des Kaisers (erstmals 1515) sich auf ein Ensemble solcher Gamben beziehe, wie es zur gleichen Zeit auch an italienischen Höfen belegt ist.[19] Dies muss allerdings Vermutung bleiben, da außer der wenig spezifischen Angabe „kay. Mt. Geygern“ nicht mehr als die Namen der Spieler bekannt sind (Caspar und Gregor Egkern, Jorigen Berber und Heronimus Hager), nichts aber zu ihren Instrumenten. Caspar Egkern erscheint einige Jahre zuvor auch als „Kay. Mayt. busaner“ bzw. „Kay Mayt pfeyffer“, demnach war er nicht auf ein bestimmtes Instrument beschränkt.[20]

„Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen krumphörner“: Schalmeien, Posaunen und Krummhörner

Als „Maister“ des zweiten Musikerwagens des Triumphzugs, „Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen, krumphörner“ (» Abb. Triumphzug Bläser), wird Hans Neuschel (ca. 1470–1533) genannt, der aber tatsächlich gar nie festes Mitglied der maximilianischen Hofkapelle war, sondern als Trompetenmacher und Stadtpfeifer in Nürnberg wirkte.[21] So sehr ihn Maximilian offenbar schätzte und oft beim Nürnberger Rat als Musiker anforderte, Neuschel seinerseits war über diese Ehre nicht nur glücklich, musste er doch wegen der Reisen zu Maximilian, die ihn manchmal „lenger dann jar und tag“ beanspruchten, seine übrige Kundschaft vernachlässigen: „das ihm dadurch sein werkstat ganz erniderlegt und er in seinem abwesen von seinem handwerk feiern, dadurch seine kunden und kaufleut verlieren und des, so er mit solchem seinem handel verdienen und erarbeiten mog, empern und allein vil schulden, darein er hievor, als er kais. maj. ein zeitlang nachgeraist sei, muss gewarten“ (Dadurch liegt ihm seine Werkstatt brach und er muss seinem Handwerk fern bleiben, wodurch er Kunden und Kaufleute verliert, und ihm das Geld fehlt, was er ansonsten verdienen würde, und viele Schulden machen muss, indem er dem Kaiser nachreisen muss).[22] Posaunisten wie Neuschel, oder der an anderer Stelle im Triumphzug genannte Hans Stewdl (oder Steydlin), waren Spezialisten, die bei besonderen Gelegenheiten gemeinsam mit den Sängern auftraten. So heißt es beispielsweise 1512 beim Reichstag in Trier, der Kaiser habe „Misse gehoret, die ist discantirt. Darinn mitl zincken vnd basunen geblasen“.[23] Demnach bliesen eine oder mehrere Posaunen die Unterstimmen einer vokal aufgeführten polyphonen Messe mit, während ein Zinkenspieler die Oberstimme spielte und vermutlich auch dazu improvisierte. Auch ist denkbar, dass ein Posaunist einen neuen bzw. zusätzlichen Contratenor spielte. (Einen möglichen Klangeindruck eines solchen „lauten“ Ensembles vermittelt » Hörbsp. ♫ La la hö hö.)

Genau diese Situation ist im Triumphzug auf dem Wagen der „Musica Canterey“ (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei) dargestellt, wo neben den Sängern ein Zinkenspieler und ein Posaunist zu sehen sind, laut dem Bildprogramm sollen hier Augustin Schubinger und Hans Stewdl dargestellt sein. Schubinger (» G. Augustin Schubinger) war offenbar der Spezialist für das Zinkspiel zu seiner Zeit (»H.Zink). Er stammte aus einer Augsburger Stadtpfeiferfamilie, die eine Vielzahl von herausragenden Bläsern hervorbrachte.[24] Augustin dürfte um 1460 geboren worden sein und ist ab 1477 als Stadtpfeifer in Augsburg belegt. Zeitweilig auch in Diensten des Markgrafen von Brandenburg und von Maximilians Vater, Friedrich III., lässt er sich zwischen 1489–93 in Oberitalien und vor allem in Florenz nachweisen, wo ja auch Heinrich Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) wirkte. Nach dem Sturz der Medici kehrte Augustin in habsburgische Dienste zurück; auch hier wiederum in einer gewissen Parallele zu Isaac, der wenige Jahre später wieder an Maximilians Hof kam. Er scheint sich erst allmählich auf dem Zink spezialisiert zu haben, wird er am Beginn seiner Karriere noch als „pfeifer“, worunter allgemein ein professioneller Musiker und Spieler von Blasinstrumenten verstanden werden kann, dann als „busauner“, womit bereits eine gewisse Spezialisierung auf Contratenor-Partien angedeutet ist, sowie auch als Lautenist genannt. Dies zeigt, dass Instrumentalmusiker in aller Regel auf mehreren Instrumenten bewandert waren. Im Anstellungsvertrag von Augustins jüngerem Bruder Ulrich beim Salzburger Erzbischof wird 1519 festgehalten, dass er seinem neuen Herrn „mit ribeben, geygen, pusawn, pfeiffen, lawtten und annders instrumentn in der musiken, darauf er etwas khann“ dient.[25] Mit Ausnahme von Tasteninstrumenten sind hier alle denkbaren Blas-, Zupf- und Streichinstrumente aufgeführt, die ganz offensichtlich zu beherrschen waren und wohl auch beherrscht wurden.

„Musica Rigal vnd possetif“: Tasteninstrumente

Der dritte Musikerwagen des Triumphzugs mit dem Titel „Musica Rigal vnd possetif“ (» Abb. Triumphzug Regal) zeigt nur einen einzigen Musiker: Paul Hofhaimer (1459–1537; » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » I. Hofhaimer) – und als sehr realistisches Detail einen Kalkanten, der die Blasebälge des Orgelpositivs bedient und ohne den jede Orgel bis zur Erfindung der mit einem Elektromotor angetriebenen Luftversorgung stumm bleiben musste. Hinter Hofhaimer sind weitere, in Transportkästen versteckte Tasteninstrumente zu sehen (laut dem Text soll eines ein Regal darstellen, das andere könnte ein Clavicytherium sein – ein Tasteninstrument mit aufrechten Saiten und einer Zupfmechanik wie beim Cembalo). Hofhaimer war seit jungen Jahren den Habsburgern als Organist verbunden, ab 1490 in Diensten Maximilians und sehr oft mit ihm auf Reisen; berühmt ist seine Klage, wie „ayn zigeyner“ umherziehen zu müssen (vgl. » I. SL Life as an Emperor’s musician).[26] Schon aus diesem Grunde waren transportable Tasteninstrumente notwendig, Hofhaimer spielte aber auch auf großen Kirchenorgeln (» Orgel). Im Auftrag Maximilians beaufsichtigte er auch den Bau von großen Orgelwerken, wie etwa in Innsbruck und Salzburg.[27] All diese Tasteninstrumente hatten aber nicht nur eine praktisch-musikalische Funktion, sondern trugen ebenso wie die darauf in seinem Namen spielenden Musiker zu dem Ansehen Maximilians bei. Das zeigt sich beispielsweise im Bericht der Gesandten aus Worms vom Reichstag in Köln 1505, die den Kirchgang Maximilians „mit sengern busunern pfyffern und orgeln und sunderdemselben mit aynem nüwen instrument der music uns gantz frembd kummen, auch demselben keynen nammen gebben“ (mit Sängern, Posaunisten, Pfeifern und Orgel und auch mit einem neuen Musikinstrument, das uns unbekannt war und für das wir keinen Namen kennen) schildern.[28] Es folgt die verwunderte Beschreibung eines Regals mit stark verkürztem Resonanzkörper und Zungenpfeifen, die im Instrumentenkorpus verborgen sind, – und welches so scheinbar ohne Pfeifen spielt. Das Aufsehen, das solche „nüwen instrument“ sowie die darauf spielenden Instrumentalkünstler erregten, gibt exemplarisch auch der Bericht über die Feierlichkeiten der sogenannten Doppelhochzeit 1515 in Wien (» D. Royal Entry) Ausdruck:

“Hat der bischof von Wienn vnd kay. Ma. Capelln mit allerlay seitenspiln das hochambt gesungen / darunter vil newe vnd kunstliche saitenspil die man vor iar nit gehabt als das man Regal nennet vnd das ain Munch an alle pfeiffen erfunden / vnd aines das vogelgesang representiert / welche dan maister Paul organist der künstlichest in allen landen geschlagen hat.”[29]

(Der Bischof von Wien hat mit der kaiserlichen Kapelle mit verschiedenen Instrumenten das Hochamt zelebriert, darunter gab es viele neue und kunstvolle Instrumente (‚saitenspil‘), die es früher noch nicht gab, wie das so genannte Regal ohne jede Orgelpfeifen, das ein Mönch erfunden hat, und ein anderes, das den Vogelsang imitiert, welche der Organist Meister Paul in allen Landen vorgespielt hat.)Ganz ähnlich ist auch der berühmte Holzschnitt von Hans Weiditz zu verstehen, der Kaiser Maximilian, die Messe hörend zeigt (» Abb. Kaiser Maximilians Kapelle). Hier sitzt, den kaiserlichen Sängern gegenüber, Hofhaimer an einem aufsehenerregenden Orgelinstrument, dem sogenannten „Apfelregal“. Der kuriose Name geht auf das Aussehen der Pfeifen zurück, „dass es wie ein Apfell vffm Stiel stehet“, d.h. über den kurzen Zungenpfeifen (der „Stiel“) steht ein runder Resonanzkörper (der „Apfel“).[30] Die eigentlich recht lauten Regale klingen dadurch weicher und auch leiser – und sehen aufsehenerregend aus.

„Musica süeß Meledey“: Instrumentalensembles

Schliesslich folgt im Triumphzug ein vierter Musikerwagen, „Musica süeß Meledey“ (» Abb. Triumphzug Süße Melodie), dessen „Maister“ Maximilian aber noch nicht bestimmt hatte. Zu sehen sind insgesamt acht Musiker, deren Instrumentarium genau festgelegt war:

„ain tämerlin, ain quintern, ain große laüten, ain Rÿbeben, ain Fydel, ain klain Raůschpfeiffen, ain harpfen, ain große Raůschpfeiffen.“[31]Während diese Angaben für die ausführenden Illustratoren offenbar eindeutig waren, ist heute die genaue Identifizierung der Instrumente schwieriger. Das „tämerlin“ ist eine Einhandflöte und Trommel, eine Art von Ein-Mann-Tanzmusikensemble, wie es etwa im Freydal mehrfach dargestellt ist. Mit „quintern“ und „große lauten“ ist ein Duo zweier unterschiedlich großer Lauten bezeichnet. Weiter folgen eine Viola da gamba und eine Fiedel oder Proto-Violine sowie eine Harfe. Bei den zwei Rauschpfeifen handelt es sich um Holzblasinstrumente, deren Rohrblatt ähnlich wie beim Krummhorn in einer Windkapsel steckt. Alle die genannten Instrumente spielten in dieser Konstellation wohl nicht gemeinsam, vielmehr sind hier verschiedene Einzelensembles zusammen dargestellt. Die Unverträglichkeit zeigt sich bereits in der unterschiedlichen Lautstärke der Instrumente, die auch die spätmittelalterliche Unterscheidung zwischen „bas“ (leise) und „haut“ (laut) spiegelt. Bezeichnet ist damit zugleich auch eine Differenzierung des Spielortes, einem Musizieren von (leisen) Saiteninstrumenten in der Kammer und vor wenigen Zuhörern gegenüber einem Aufspielen von (lauten) Blasinstrumenten im Freien oder einem großen Saal.

Die Instrumentalmusik am Hofe Maximilians I.

Lässt sich das Personal der maximilianischen Instrumentalmusik aufgrund von Archivalien und Dokumenten noch einigermassen leicht erfassen, so ist es ungleich schwieriger, die von diesen Musikern gespielte Musik zu identifizieren bzw. überhaupt zu greifen. Das liegt vor allem daran, dass die instrumental aufgeführte Musik zu dieser Zeit noch kaum aufgezeichnet wurde, sondern eine buchstäblich schriftlose Praxis war. In diesem Sinne „improvisierten“ die Musiker auch nicht, sondern sie musizierten ganz selbstverständlich sozusagen „auswendig“, sei es auf der Basis einer mündlichen Tradierung oder als ad hoc-Entstehung.[32] Schriftliche Aufzeichnungen waren vor allem für Vokalmusik üblich – entsprechend zeigt im Triumphzug nur der Wagen der „Musica Canterey“ ein Notenpult, alle übrigen Musiker musizieren ohne Noten. Spezifische Schriften für Instrumentalmusik, sogenannte Tabulaturen, existierten zu Beginn des 16. Jahrhunderts für Tasteninstrumente und Laute. Und in beiden Aufzeichnungsweisen ist tatsächlich auch Musik von Musikern Maximilians überliefert: von Paul Hofhaimer und von Adolf Blindhamer (vgl. Kapitel “Lute Intabulations by Adolf Blindhamer”). Weitere Quellen für auch instrumental aufzuführende Musik erschließen sich anhand des Titelblatts eines in vier Stimmbüchern gedruckten Liederbuchs (Fünfundsiebzig hübsche Lieder, Köln: Arnt von Aich, 1514-1515): „In dissem buechlyn fynt man .Lxxv. hübscher lieder myt Discant. Alt. Bas. vnd Tenor. lustick zů syngen. Auch etlich zů fleiten / schwegelen / vnd anderen Musicalisch Instrumenten artlichen zů gebrauchen.“[33] Demnach können die Lieder, für die sich im Stimmbuch für den Tenor separat stehende Liedtexte finden, auch instrumental aufgeführt werden. Bei Aichs Liederbuch handelt es sich den Nachdruck von mindestens zwei Sammlungen der Schöffer-Werkstatt, die Repertoire aus dem Umkreis Maximilians enthielten.[34] Damit lassen sich auch die beiden Augsburger Liederdrucke „Aus sonderer künstlicher Art“ (» 1512) und “[68 Lieder]” (» 1513), die in der Offizin von Erhart Oeglin erschienen, für eine Instrumentalmusik Maximilians reklamieren, wenn auch festgehalten werden muss, dass es sich hierbei klar um vokal konzipierte Musik handelt, die nur alternativ auch instrumental aufgeführt werden konnte.

Etwas anders sieht dies bei einer handschriftlichen Quelle aus, für die ebenfalls eine lose Verbindung zum Repertoire der Musiker Maximilians vermutet wurde: Im „Augsburger Liederbuch“, einer zwischen 1505 und 1515 entstandenen Musikhandschrift mit einem gemischtem Inhalt von Liedern, Chansons und Motetten (u. a. von Josquin Desprez, Jacob Obrecht, Heinrich Isaac (» D-As Cod. 2o142a), Alexander Agricola und Ludwig Senfl (» G. Kap. Senfls musikgeschichtliche Bedeutung) sowie auch einigen Tanzsätzen.[35] Diese hier meist unbezeichneten Sätze lassen sich als italienische Tänze identifizieren, wie sie Musiker wie etwa Schubinger aus ihrem Dienst in Italien mitbrachten. Allerdings gibt die schriftlich fixierte Musik nur eine ungefähre Vorstellung von ihrer mitreißenden Aufführungspraxis. Die in der Literatur in diesem Zusammenhang zitierte Äusserung Maximilians, der 1479 aus den Niederlanden schreibt, seine Pfeifer hätten ihn „schier drei oder viermahlen zue Todt gepfiffen“ bezieht sich allerdings auf pfeifende Kanonenkugeln, deren Beschuss er durch französische Büchsenmeister ausgesetzt war.[36]

Lautenintabulierungen von Adolf Blindhamer

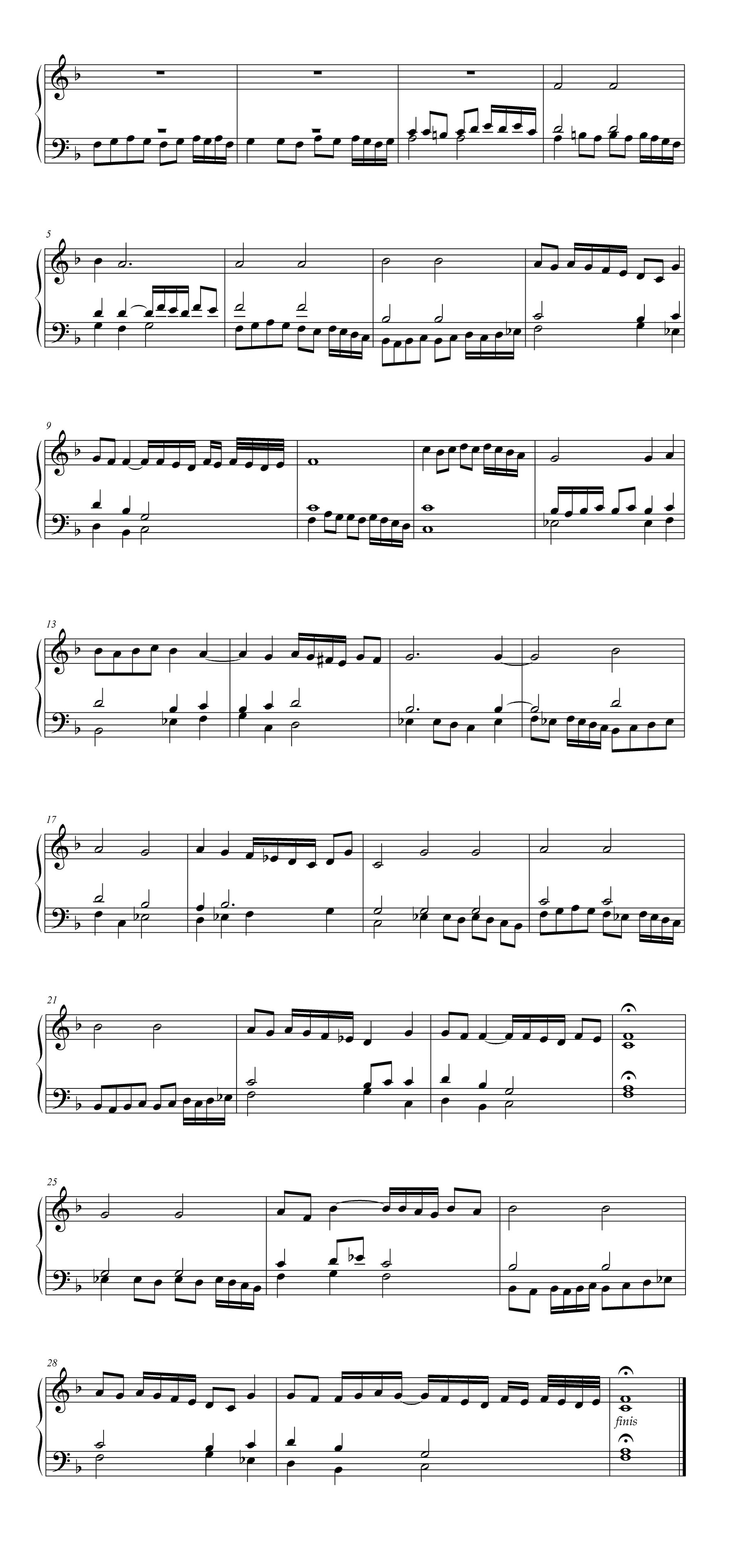

Ein schmales Manuskript mit Lautenintabulierungen Blindhamers (» A-Wn Mus. Hs. 41950), ist mit einer mutmasslichen Datierung um 1525 nicht nur eine der frühesten erhaltenen Quellen mit Lautenmusik, sondern auch fast die einzige Quelle aus dieser Zeit, die komplexere Musik eines professionellen Spielers aufzeichnet und nicht didaktisch vereinfachte Musik für Anfänger.[37] Es enthält ein langes Praeambulum (eine fantasieartig freie Form), weiter hier so bezeichnete „Mutetae“ (gemeint sind Instrumentalsätze) sowie Intabulierungen von Vokalsätzen und einige Tanzsätze. Neben Blindhamer selbst werden mehrere Komponisten genannt: Josquin Desprez, Paul Hofhaimer (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » I. Hofhaimer), Heinrich Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) und Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl). Hierbei handelt es mit Ausnahme von Josquin um Musiker, die eng mit Maximilian verbunden sind. Diese Nähe erklärt vielleicht auch die Existenz eines Unikums, einer also nur in dieser Handschrift überlieferten Muteta mester paulus hofhamer (» Notenbsp. Muteta mester paulus hofhamer).

Der Titel trägt den Zusatz „mit 3 stymen“, was bedeutet, das bei der Intabulierung drei Stimmen berücksichtigt wurden (andere Intabulierungen in der Quelle nennen sogar vier Stimmen, was als Hinweis auf die besondere Kunstfertigkeit des Intabulators wie des Spielers zu verstehen ist, mehrere kontrapunktisch geführte Stimmen in den Lautensatz zu retten und zu spielen). Musikalisch fallen weiter die virtuosen Umspielungen auf, in der Zeit „Colorierung“ genannt. Blindhamers mutmaßlicher Schüler Hans Gerle beschreibt sein Spiel folgendermassen:

„Es hat auch gedachter Adolff (damit sein kunst vnd schickligkait erweittert werde) diese art gefürt / die dann alle Künstner der Musick vnd derselben Instrumenten haben sollen / wenn er bey verstendigen der Musica / oder vor berümbten Syngern geschlagen / hat er sich gleichwol zuuor in seinen Preambeln dermassen hören lassen / das sein geradigkait vnd kunst gewaltig erschinen ist / zusampt dem / so er zu einem gesatzten stücklein gegriffen / hat er das erstlich / wie es in noten gestanden / mit wenig Coloraturen / zum andern mit wolgestelten leuflein geziert / vnd zum dritten durch die Proportion geschlagen vnd volfürt / Vnd doch einer solchen gestalt / damit der süssigkait vnd vollkomenheyt des gesangs nichts benomen worden ist.“[38]Nach einem Präludieren, das neben dem Einstimmen des Instrumentes auch dem der Zuhörer diente und virtuose Passagen beinhaltete, spielte Blindhamer eine schriftlich fixierte Komposition, etwa die Intabulierung eines mehrstimmigen Vokalsatzes. Diese erklang ein erstes Mal nur kaum verziert, darauf folgte eine mit Läufen und Umspielungen stark ornamentierte Version. Schließlich konnte die Vorlage bei einer weiteren Wiederholung auch noch rhythmisch variiert werden, wobei in keinem Fall die zugrundeliegende Komposition verfremdet wurde. Bemerkenswert ist auch das hier erwähnte mehrfache, dabei stets variierte Spiel der in der Regel ja nur kurzen Stücke.

Der nur als Lautenintabulierung erhaltene Satz von Hofhaimer weist auf die großen Lücken hin, mit denen in der Überlieferung von Musik gerechnet werden muss, denn sicher handelt es sich hier nicht um eine Originalkomposition Hofhaimers für Laute, sondern nur um eine Adaption für dieses Instrument. Solche Lücken sind beachtlich in der überlieferten Musik von Paul Hofhaimer: Von ihm, der 1480 als Organist am Habsburgerhof in Innsbruck auf Lebenszeit angestellt wurde, ist erstaunlicherweise kaum liturgische Orgelmusik erhalten, obwohl hierin seine hauptsächliche Tätigkeit und sein Ruhm begründet lag. Die für ihn so bedeutsame Erhebung in den Ritterstand 1515 erfolgte in Wien im Rahmen der Doppelverlobung der Enkel Maximilians. Im Anschluss an die Zeremonie spielten die kaiserlichen Trompeter eine Fanfare und die kaiserliche Kapelle sang das Tedeum und „in Organis Magister Paulus, qui in universa Germania parem non habet, respondit“ (auf der Orgel antwortete Meister Paul, der in ganz Deutschland keinesgleichen hat).[39] Dieses „Beantworten“ beschreibt die sogenannte Alternatim-Praxis, bei der die Verse des Hymnus abwechselnd gesungen und von der Orgel gespielt werden. Der Organist basiert seinen Part auf dem liturgischen Tenor und zeigt sein Können darin, wie kunstvoll er den Cantus firmus einkleidet. Erhalten sind von Hofhaimer gerade nur zwei solcher Orgelversetten, die vielleicht von seinen Schülern aufgezeichnet wurden – Hofhaimer selbst extemporierte sie wohl. Sein Schüler Hans Buchner beschreibt verschiedene Verfahren einer solchen Choralbearbeitung (sogar am Beispiel des Tedeums), die Praxis Hofhaimers erschließt sich aber auch aus den beiden erhaltenen Orgelstücken. Vor allem im „Recordare“, basierend auf dem liturgischen Tenor, das aber auch wie ein Hymnus einem Salve Regina angehängt wurde, zeigen sich die vielfältigen Möglichkeiten eines Umgangs mit dem Cantus firmus, der in dem dreistimmigen Satz in verschiedenen Stimmen und kontrapunktischen Techniken erklingt.[40]

[1] Zum Triumphzug, seinen unterschiedlichen Versionen und der komplexen Entstehungsgeschichte informiert Appuhn 1979 und Michel/Sternath 2012; zur Bedeutung für Maximilian Müller 1982; zum Verhältnis zwischen Abbildung und Realität Polk 1992; das Zitat stammt aus der frühesten erhaltenen Formulierung des ikonographischen Programms des Triumphzugs 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (Zitat aus den Augsburger Baumeisterbüchern von 1491, den Kassenbüchern des Rats über Ein- und Ausgaben).

[5] Vgl. Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] Vgl. Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Zitiert nach Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] Vgl. Schwindt 2012.

[10] Sie erhält im Juni 1520 bei der Auflösung der Hofkapelle nach dem Tode von Maximilian die hohe Summe von 50 Gulden „zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung“; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Wie beispielsweise „Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher“, die 1491 ausdrücklich für ihre Dienste „bei Tanz“ an der Fasnacht bezahlt werden; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] Für eine Zusammenstellung der musikrelevanten Abbildungen siehe Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] Vgl. Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[17] Vgl. Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] Vgl. Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (dort auch zum Folgenden).

[20] Laut Zahlungen in den Augsburger (D-As) Baumeisterbüchern Nr. 103 (1509), fol. 24v, und Nr. 104 (1510), fol. 28; freundliche Mitteilung von Keith Polk.

[21] Vgl. Jahn 1925, 10 ff., und Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] Vgl. Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] Vgl. Brief von Paul Hofhaimer an Joachim Vadian am 14. Mai 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So der Wortlaut in der Formulierung des ikonographischen Programms in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] Vgl. Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, Titelblatt des Tenor-Stimmbuchs; zur Datierung siehe Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] Vgl. Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] Vgl. Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[36] Senn 1954, 26. Die Korrektur nach dem Schreiben Maximilians in A-Wn, Cod. 10100b, 15r–v, ediert bei Kraus 1875, 39 verdanke ich Grantley McDonald, der auch auf das Geschützmodell der ‚Lauerpfeif‘ hinwies (KHM Wien, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, A 74), bei der seitlich zum Geschützrohr zwei Pfeifen mit Labium angebracht sind, mit denen Pfeiftöne erzeugt werden können; siehe Krammer 2025.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; Faksimile und Beschreibung in Kirnbauer 2003. Lautentabulaturen der nächsten Generation aus dem süddeutschen Sprachraum beschreibt » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] Vgl. Moser 1966, 26 und 182, Fußnote 35.

[40] Vgl. Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; siehe auch » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Martin Kirnbauer: „Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).