Schlaglicht: Life as an Emperor's Musician

One of the most widely acclaimed musicians of the early sixteenth century, celebrated in both image and verse, was the Imperial court organist Paul Hofhaimer (1459-1537). Born in the small Austrian town of Radstadt, it would seem that Hofhaimer soon developed the musical skills and royal connections that paved the way for a highly successful career at court. An ode to the musician, written by the humanist Conrad Celtis and published in the Harmoniae poeticae of 1539 (» I. Kap. A book in memory of Hofhaimer), seems to refer to the tuition on the organ received by Hofhaimer at the court of Emperor Friedrich III. In 1478, he entered the service of the Emperor’s cousin Archduke Sigmund, at Innsbruck, transferring his allegiance to Friedrich’s son, the ever-itinerant King of the Romans Maximilian I, in 1490 (» I. Kap. Music traditions of the Innsbruck court).[1] While employed by Sigmund and Maximilian, Hofhaimer not only acquired the reputation of a gifted performer (no doubt aided by his travels in Maximilian’s entourage), but was also called on for his expertise in the construction and repair of organs and for his teaching of young organists, including several sent to him by the Saxon court.[2] Yet, Hofhaimer’s accomplishments extended beyond performance and teaching on the organ to include the composition of music for instruments and also voice. While, unfortunately, few examples of his pieces for organ have survived (perhaps indicating that much of his playing in this respect was improvised), several German songs and some Latin-texted works written by the organist are known to us today.[3]

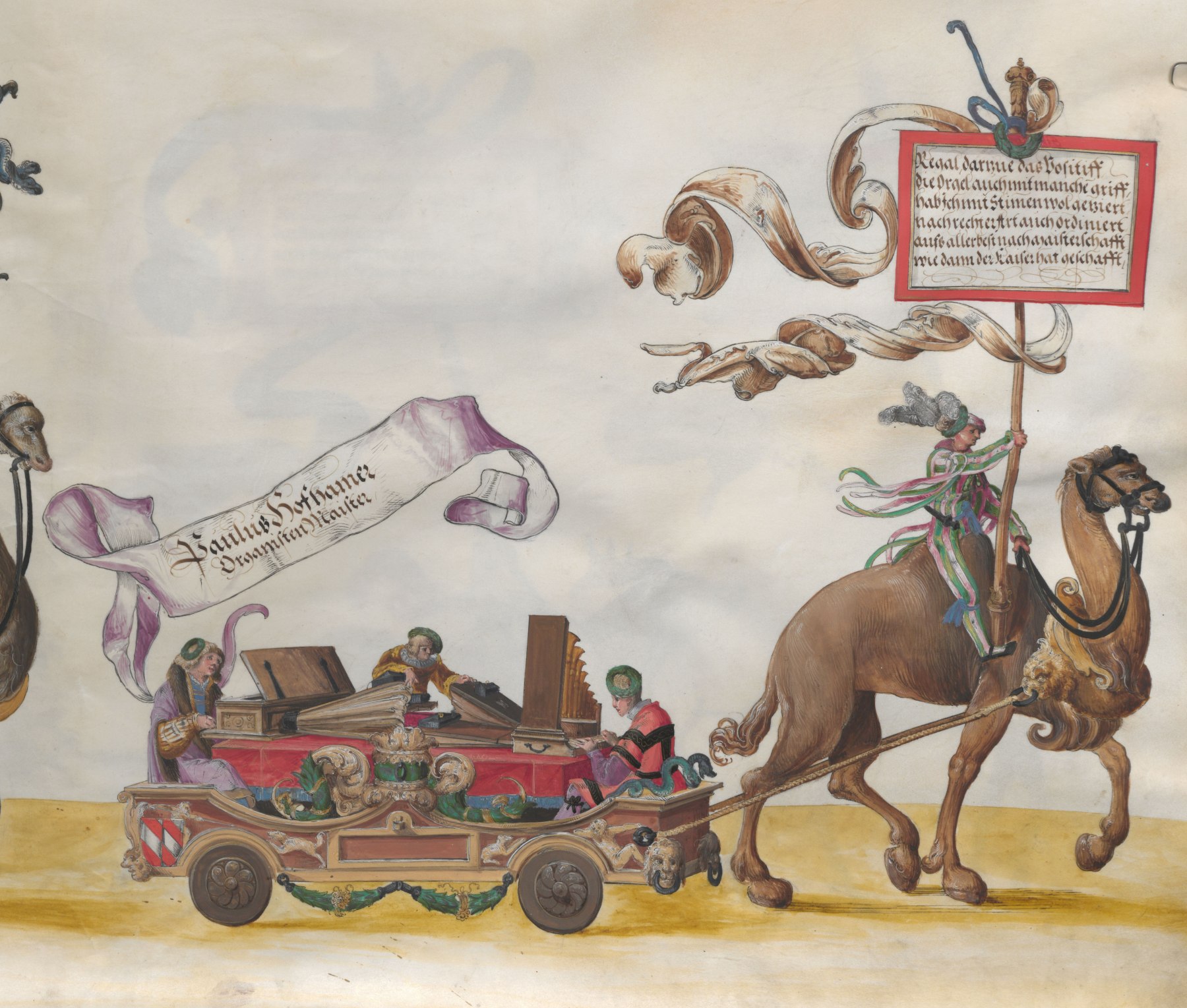

Maximilian’s admiration of Hofhaimer’s musical abilities is reflected in the organist’s central position amongst the musical carts of the Emperor’s Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Regal). The plans for this publication, dictated by Maximilian to his secretary Marx Treitzsaurwein, included the following instructions for the depiction of Hofhaimer:

Auf demselben Wägenle solle sein Rygal vnd Schalmeyenpossetif vnnd darauf man schlagen solle. Item der maister solle sein Maister pauls Organist, vnnd sein Reim auf die maynung gemacht werden: Wie Er auf des kaisers Angeben die Musica künstlichen gemert vnd erclert hab.[4]

(On the same small cart, there should be a regal and a ‘shawm-positive’, on which there should be people playing. Item the master should be Master Paul, organist, and his rhyme should have the following sense: How, on order of the Emperor, he skilfully extended and enlightened music.)[5]

Although the original coloured drawings of the musicians in the Triumphzug – the design on which the woodcuts were based – have been lost, a late sixteenth-century copy (A-Wn Cod. Min. 77) indicates that there were striking differences between these original illustrations and the final prints. The hand-drawn miniature of Hofhaimer (» Abb. Hofhaimer in the Triumphzug drawings) seems to follow the Emperor’s original instructions closely in the instruments it depicts: Hofhaimer, identified by his banderole on the left, plays a regal while his colleague plays a positive organ that has shawm-like pipes, both musicians connected by a single calcant. In the woodcut (» Abb. Triumphzug Regal), Hofhaimer is the only musician to be seen, surrounded by various keyboard instruments and this time playing on a standard positive organ, its bellows again operated by a calcant. Despite the differences between the two images, both present possible portraits of the celebrated organist (although the reliability of the copies of the miniatures are naturally called into question in this respect).[6] Furthermore, both images point to Hofhaimer’s heightened social status as a result of his employment, and ennoblement, by Maximilian: the coat of arms that had been bestowed on him in 1515 is clearly displayed in both the manuscript and wood-cut images as a further mark of respect for this most esteemed instrumentalist.[7]

Hofhaimer’s rise to noble status

An appointment at the court of Maximilian I would have been one of the greatest possible achievements of a professional musician working at the turn of the sixteenth century. Instrumentalists in Maximilian’s employ benefitted not only from much-needed financial support but also from their association with one of the most politically and musically significant institutions of the age (» I. Instrumentalkünstler). Yet, what was life really like for a musician in the emperor’s service? Did this really bring the rewards one might expect of a position at the imperial court? A letter written by Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadianus on 6 November 1515 (» Abb. Hofhaimer’s letter to Vadian) sheds important light on the different sides of such a prized post.[8]

It is the first paragraph of this letter that is particularly interesting in this respect. Here, Hofhaimer writes:

Ersamer hochgelerter gunstiger lieber herr Maister Joachim[.] Mein willig dinst seind euch altzeit zuvoran berayt und fug euch zu wissen das ich seyd der zeit als ich von Wyenn haym khummen bin[,] pald widerumb ausreyten han müssen und bey kayserlicher Majestät zu Ynnsprugk und anderer ennde wol vj wochenlanng ausbeliben[;] han euch deshalben dye ding nit ee schicken mugen biß ich ytz widerumb haym bin khümmen. Unnd schik euch hyemit in aynem Ror verpetschafft iiij augspurger ellen atlas zu aynem Wammas als ich euch verhayssen hab[.] Dabey ligen zway Wappen[:] das ayn mit dem lateinischen Titel wellet dem Ludwico Sennfel geben[,] das ander mit dem Teütschen titel wellet dem Wolfgango Organisten geben[;] dann di kayserliche Majestät hat ytz zu Ynsprugk in ansechung meiner emphangen Ritterlichen Eer mich noch höcher gefreyet unnd geadelt[,] mich Turnierersgnoß gemacht als ir an dem helmm diser Wappen sechen werd[;] Auch mir im Thewtsch den titel geben das man mir schreyben unnd mich nennen sol her Paulsen Hofhaimer kayserlicher Majestät obristen Organisten und nymmer Maister Pauls etc.[9]

(Venerable, most learned, gracious dear Sir, Master Joachim. As always, I offer my obedient service to you and can inform you that as soon as I returned home from Vienna, I had to ride out again to his Imperial Majesty in Innsbruck and remained there for some six weeks; I was therefore not able to send you the item until I returned home just now. And I am sending you herewith, in a sealed tube, four Augsburg cubits of atlas [i.e. satin cloth] for a doublet, as promised. With it there are two coats of arms: the one with the Latin title is to be given to Ludwig Senfl, the other with the German title to the organist Wolfgang; for in view of my receipt of the honour of chivalry, His Imperial Majesty has now further celebrated and ennobled me in Innsbruck, has made me a fellow of the joust, as you will see from the helmet on this coat of arms; and also gave me the German title, with which I should be addressed in writing and known: Herr Paul Hofhaimer, chief organist of His Imperial Majesty and no longer Master Paul etc.)

Hofhaimer makes reference to several recent honours bestowed on him by the emperor — the culmination of decades in Maximilian’s service and a reflection of the great esteem in which he was held by his employer. The organist had recently returned from the magnificent double wedding in Vienna that had united the House of Habsburg with the Hungarian royal dynasty (» D. SL Music for a Royal Entry). There, he had been knighted by his sovereign and, as Hofhaimer explains to Vadianus, further accolades then followed in Innsbruck (» I. Memorialkultur. Remembering Paul Hofhaimer). The tax books of Augsburg, where Hofhaimer was then resident, reflect this change in his status: whereas in 1508 he is identified there as ‘maister pawls organist’, in 1516 he receives the title ‘Her[r] Pauls hofhaimer Ritter Kay[serlicher] M[ajestä]t Organist’ (Herr Paul Hofhaimer, Knight. His Imperial Majesty’s Organist).[10]

Though Hofhaimer’s rise to noble status was not without precedent (the organist Conrad Paumann was likewise the recipient of a knighthood), it was nevertheless unusual — he was the only musician in Maximilian’s employ to be honoured in this way, having previously been the beneficiary of several other favours bestowed by the emperor.

Financial rewards

Under his previous employer, Archduke Sigmund (» I. Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck), Hofhaimer already appears to have enjoyed great acclaim, fast becoming one of the best-paid employees of the court through a substantial salary and subsistence allowance, as well as additional payments such as for instrument repairs and teaching.[11] Hofhaimer’s salary continued after he entered the service of Maximilian in 1490, with the sovereign doubling his income to 200 guilders in June 1494. Similar increases followed in later years.[12] Financial records of the court also include regular references to extraordinary rewards made to the organist. For example, in 1493, Maximilian had the mortgage and interest paid off on Hofhaimer’s home in the Silbergasse, Innsbruck, which was also newly roofed and painted at the expense of the emperor in 1497. Other privileges included a tun of wine received by the organist in January 1498.[13]

Although other court musicians did not enjoy the same rights as the acclaimed organist, the earnings from their posts enabled many to make similar investments in their homes.[14] The trumpeter Konrad Tollenstein was able to build two houses through his (albeit sometimes delayed) salary payments: one in ‘Aintzing’ (presumably the nearby Tyrolean village of Inzing) in 1504, and then two years later, in Innsbruck.[15] Tollenstein’s trumpeter colleague Hans Kugelmann was recorded as lodging with him when Maximilian’s entourage returned to Innsbruck in 1518.[16]

For musicians of the court like Hofhaimer, arrangements were made which would provide for their families after their demise. Such financial undertakings were pledged to Hofhaimer back in 1480, when part of his salary was promised to his first wife Susanna in case of his death; these terms were again affirmed by Maximilian in 1493, after the organist married for a second time.[17] A similar agreement was reached for the piper Anthoni Dornstetter (» I. Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I) in 1503, when a portion of his 100 guilder income was likewise guaranteed to his wife, should the need arise.[18]

The itinerant court

Yet, despite the benefits enjoyed by many of those in the employ of the emperor, a post at the royal court was not without hardship. In his letter above, Hofhaimer alludes to the strains of his role there, which required him to move frequently from city to city – in this case, from his home in Augsburg to Vienna, and then to Innsbruck. This itinerancy was a long-standing requirement of an appointment at the court: within the first year of Hofhaimer’s post there, he was first made to travel to Linz, then to Augsburg or Ulm and later ‘zu der Kü[niglichen] M[aje]st[ät] gen Wien oder wo er die vindet’ (to his Royal Majesty in Vienna, or wherever he is to be found).[19] In another letter to Vadianus, dated 14 May 1524 and written after Hofhaimer had entered the service of the Archbishop of Salzburg, he declared: ‘Ich dannck got, das ich nymmer wye ayn zigeyner umraysen bedorff.’ (I thank God that I no longer have to travel like a gypsy). [20]

The monetary and other rewards received by Maximilian’s musicians were often incentives to fulfil the peripatetic demands of their posts. For example, when Hofhaimer’s income was doubled on 5 June 1494, this was on the condition that he would be ready to serve at Imperial Diets and when otherwise required.[21] Similar instructions were given to the organist in subsequent years, those of 1506 noting provision for two horses and two companions for his travels.[22] In 1507, on the orders of the court, Hofhaimer moved to Maximilian’s beloved and more conveniently located Augsburg, so that, as the emperor instructed the city, so wir Ine erfordern, desst furderlicher zu uns komen mög’ (when we require him, the same can come to us more swiftly).[23] These demands were evidently met in the years that followed: for example, on 21 December 1512, his secretary Marx Treitzsaurwein wrote to the Augsburg council to request that the organist attend Maximilian at the Imperial Diet in Worms.[24]

Hofhaimer was not the only employee burdened by the travels of the court; his musician colleagues were likewise often part of the entourage that accompanied the emperor through his territories. The trombonist Hans Neuschel, who was employed on an ad hoc basis with no regular salary, received regular requests to leave his hometown of Nuremberg in order to serve Maximilian, which he did with some reluctance (» I. Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I). Other instrumentalists were more closely tied to the political demands of the emperor’s reign. The court’s financial accounts include several payments for travel expenses and horses for the group of brass instrumentalists and drummers who were permanently employed there. As such, like Hofhaimer, they were often called on to join Maximilian at significant political gatherings. However, their additional involvement in his military campaigns brought further challenges. In 1500, the brass instrumentalist Jacob Nagel was awarded payment ‘fur seinen schaden Im Sweytzer krieg’ (for his injuries in the Swiss war) and in 1514, the trumpeter Urban Tollenstein fell in the war against Venice, his widow receiving a pension of 32 guilders annually for life.[25]

Financial constraints

It was not only the peripatetic nature of the court that the musicians found troublesome. The financial constraints of Maximilian’s reign also had implications for those in his service and the delayed payment of salaries could cause great hardship for instrumentalists and their families. The trumpeters of the court seem to have been particularly affected by these financial difficulties. In 1514, after concerns about the welfare and family of the trumpeter Jörg Tuttenkofer were registered with the court, he received 400 of the 640 guilders owed to him. Tuttenkofer also transferred to a new post as a messenger once he was unable to continue as a brass instrumentalist due to loss of his teeth.[26]

The frequent expenses incurred by musicians for accommodation and food during their travels also often went unpaid. At the Imperial Diet in Worms 1495, there were such long delays in payments for the trumpeters’ lodgings that the instrumentalists remained there until the following year. The same trumpeters would not receive their overdue salaries until 1497 and even then, their travel expenses remained unresolved.[27] These financial difficulties continued for the rest of Maximilian’s reign: in autumn 1518, his entourage was denied lodgings in Innsbruck, as a result of long-standing overdue payments by the court. The music-loving emperor departed his residence just two days later, never to return.[28]

The bestowal of Hofhaimer’s knighthood, as described in his letter to Vadianus, clearly indicates the extent to which Maximilian was willing to honour one of his musicians, and many instrumentalists similarly enjoyed the status and salary associated with an appointment at the imperial court. Yet, even for the most privileged of these musicians, the reality of such a post was not without its challenges. As Hofhaimer indicates in his letter, the court’s travels were relentless and burdensome – even more so for those who did not enjoy the same income or favours as the acclaimed organist. Instrumentalists of lesser status often endured great hardship caused by financial losses, some of which were not recovered during the emperor’s lifetime.

[1] Moser 1929, 9-10, 16-17.

[2] In 1494, the Saxon Dukes Friedrich and Johann wrote to Archduke Sigmund to request that Hofhaimer accept their ‘diener vnd lieben getrewen Linharten Argen’ as a pupil (see zur Nedden 1932-3, 27); in 1516, it was agreed that Hofhaimer would accept a further two pupils from the Saxon court, both for a period of two years: see Moser 1929, 45-6.

[3] Paul Hofhaimer 2004 und 2009.

[4] Schestag 1883, 158-9.

[5] This and the following translations by Helen Coffey.

[6] The charcoal drawing by Albrecht Dürer once thought to depict Hofhaimer (and used as book cover in Moser 1929) probably represents a different person, according to information gratefully received from Prof. Artur Rosenauer, Wien.

[7] Myers 2007, 16-17.

[8] Kantonsbibliothek Vadiana, St. Gallen, VadSlg Ms. 30, Brief 60: Paul Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadian, Augsburg, 6 November 1515. See also » I. Memorialkultur. Remembering Paul Hofhaimer.

[9] Abbreviated words here have been expanded in full (additional letters italicised) and punctuation has been added in square brackets for clarity. For a full transcript, see Arbenz 1890-1913, i, 67.

[10] Schuler 1995, 19-20.

[12] Schwindt 2018c, 60.

[13] Senn 1954, 31-2; Moser 1929, 23, 178-9.

[14] On musicians’ home ownership, see Busch-Salmen 1992.

[15] Busch-Salmen 1992, 65; Senn 1954, 20.

[17] Senn 1954, 12; Moser 1929, 17.

[18] Wessely 1956, 98.

[19] Moser 1929, 19.

[20] Arbenz 1890-1913 iii, 70.

[21] Moser 1929, 179.

[22] Senn 1954, 32. Hofhaimer was likewise provided with a horse by the court in 1494; see Moser 1929, 179.

[23] Schuler 1995, 18. See also Schwindt 2018, 60.

[24] Schuler 1995, 20.

[25] Wessely 1956, 108; Waldner 1897/98, 32; Senn 1954, 21-22.

[26] Waldner 1897/98, 53; Senn 1954, 20.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Helen Coffey: “Life as an Emperor’s musician” in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/kapitel/schlaglicht-life-emperors-musician> (2021).