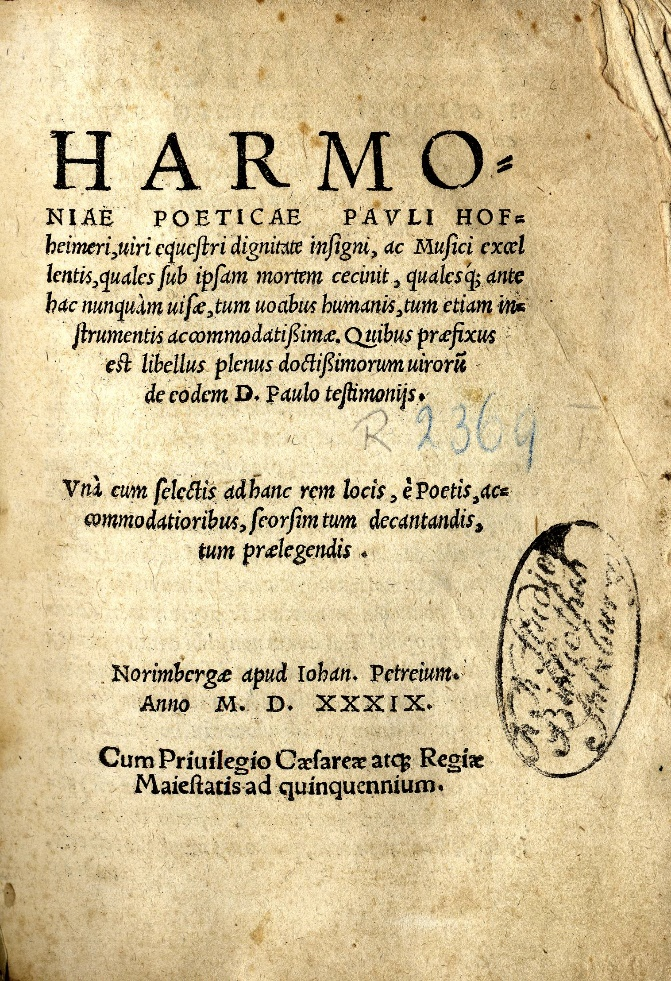

A book in memory of Hofhaimer: the Harmoniae poeticae of 1539

In 1530 a young Bavarian humanist and musician, Johannes Stomius, established a private Latin school at Salzburg. Before long Stomius had become one of Hofhaimer’s intimate circle, and the old man entrusted to him the task of publishing the literary testimonials he had been collecting over the years, in a collection dedicated to Matthaeus Lang. In return, Hofhaimer agreed to compose a series of homophonic settings of poems by Horace, Ovid, Vergil and Prudentius, which were to be used in Stomius’ school. The models for this collection were Celtis’ edition of » Melopoiae (1507), composed by Petrus Tritonius and others (» I. Odengesang), Ludwig Senfl’s » Varia carminum genera (1532) and Sebastian Forster’s » Harmoniae Prudentianae (1533).[13] Given Hofhaimer’s diffidence about his own standing amongst the humanists at court, it is ironic that his last works should have been exercises in that most humanistic of musical genres, the humanist ode-setting. In 1537, while completing his cycle of settings of Prudentius, Hofhaimer died. Once a legal wrangle over the fate of Hofhaimer’s papers had been settled, the collection » Harmoniae poeticae was printed at Nuremberg by Johannes Petreius in 1539.

The resulting publication is really two books in one.[14] The larger part of the book comprises Hofhaimer’s ode settings (» Hörbsp. ♫ Iam satis terris und » Hörbsp. ♫ Maecenas atavis), to which Stomius added another nine by Senfl, one by Hofhaimer’s assistant organist Gregor Peschin, and one by an anonymous composer, perhaps Stomius himself. The ode settings are preceded by thirty-seven pages of poems and letters collected over the years by Hofhaimer, the so-called libellus, introduced by Stomius’ dedication of the whole work to Matthaeus Lang .[15] The keynote of Stomius’ dedication is “memory”:

“[…] what is left to commend this great man and to promote his immortal fame, than to recall in the memory of men the lively powers of his mind, to examine his talents and evaluate them carefully? These cannot be appreciated anywhere more clearly than in his offspring, that is, in his writings and in the success of his students. […] It seemed a great shame to me that, either through ignorance or the ingratitude of the age, people gave no more thought to Paul’s memory, the one thing he most cared about. For this reason I wanted to save something, if only a shadow, of his memory from oblivion.”

Stomius presents memory as something that is constantly threatening to be lost. He reminds Lang that “if the lawyer Georg Teisenperger had not been so diligent about preserving the memory of the deceased, those papers would have perished entirely.” Stomius also presents a conscious reminiscence of Hofhaimer’s attitude to the question of fame and memory:

“I often remember him saying that he, already on the threshold of old age, was not motivated by the desire for glory, but since the writings of those great men had been preserved, he was reluctant to let them perish, not so much for his own sake as for that of Germany as a whole, so that we might have some means to defend ourselves against those foreigners who accuse us of being ignorant in this art.”

In the light of Hofhaimer’s correspondence with Vadianus, his protestations cannot but strike the reader as disingenuous.

Amongst the earliest of the texts in the libellus are those by Celtis (who died in 1508) and Fantin Memmo, evidently written not long after his brother Dionisio’s return to Venice from his apprenticeship under Hofhaimer in 1507. Towards the end of the collection are also several elegies. Surprisingly, some of these were written in the second decade of the sixteenth century, more than twenty years before Hofhaimer’s death. At least one (possibly two) was written in 1513 by Vadianus, who describes himself as “an admirer of [Hofhaimer’s] talent and skill.” Another, by Riccardo Sbruglio, was written after Hofhaimer’s elevation to the peerage in 1515, but before Maximilian’s death in 1519. Sbruglio also contributed a lament on the death of Hofhaimer’s second wife Margarete, who died in 1518, and probably also an epitaph to Hofhaimer’s father, which concludes: “Why is Paul remembered with such reverence on earth? He was the invincible master of harmony.” (Again this epitaph touches upon the theme of remembrance, “Gedechtnus”.) The latest poems in the libellus are laments written after Hofhaimer’s death, including two by Stomius, one by one of his students, and two by the Salzburg statesman Hieronymus Anfang. The contents of the libellus were thus written over the course of thirty years or more, and represent a collection of texts carefully selected – and in some cases actively solicited – to project a carefully cultivated image of their subject, Hofhaimer.

The » Harmoniae poeticae thus serves not only as a collection of music, but equally as an analogue in print to Maximilian’s cenotaph at Innsbruck, an artistic memorial planned by its subject over many years, and brought to completion after his death through the force of his personality and the loyalty of those who survived him. In his panegyric on Hofhaimer, Vadianus had written that “there is no truer mark of a prince than if he loves, fosters and protects those endowed with exceptional talent in the honest arts, for this is the way for them to achieve eternal remembrance. The Emperor Maximilian has come to realise this with others, but especially with Paul [Hofhaimer].”[16] It is understandable that Hofhaimer, whose artistic excellence reflected glory on his patron, should have wanted to create a similar monument to himself, mindful of Maximilian’s injunction that a man should take care that his memory last longer than the final stroke of the bell at his funeral. Just as Maximilian had been involved in the creation of his own cenotaph for some seventeen years before his death, Hofhaimer collected literary testimonia in his own honour for over three decades. The similarities between Maximilian’s cenotaph and Hofhaimer’s Harmoniae poeticae are made particularly clear in one of Vadianus’ epitaphs to the composer; here the poet imagines Hofhaimer addressing the reader after his death, concluding with an artful literary allusion to Ovid:

Attamen, ut cernis, iaceo sine luce cadaver,

Marmoreusque premit membra sepulta lapis.

Tu, si nomen amas Pauli, sique ars tibi cordi est,

Qua valuit, vivo flumine saxa riga.

Manibus et functis vitam requiemque precator

Caetera de nobis fama superstes erit.[17]

(But now, as you see, I lie here, a corpse shut up in the darkness,

And a marble slab weighs down my buried limbs.

If you love the name of Paul, and if you treasure the art

In which he excelled, shed a tear upon this stone.

Pray for the souls of the departed, for their eternal life and their rest;

Of all we are, only our reputation shall survive.)

[13] See » I. Odengesang.

[14] Modern edition: McDonald 2014.

[15] McDonald 2014, 2-41.

[16] McDonald 2014, 12: “Neque est quicquam (ut in summa referam) Principe magis dignum, quam si quibusque ingenuis artibus præstantes animos amet, foueat, tueatur. Datur enim ex hoc æternæ sibi memoriæ occasio. Hoc diuus Maximilianus, cum in alijs, tum in Paulo cognouit.”

[17] McDonald 2014, 34; cf. Moser 1929, 67.

Herrmann 1997 | Hirzel 1909 | Hofhaimer 1539 | Moser 1932/1933 | Näf 1945 | Reutter 1997 | Sallaberger 1997 | Schuler 1995

[1] Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesarchiv, Hs 208/1, fol. 86v. All English translations in the present article are by Grantley McDonald.

[2] Modena, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio Principi Esteri 1623, b.2/3,2,11, 1r; cf. Ludwig Fökövi, “Musik und musikalische Verhältnisse am Hofe von Matthias Corvinus”, in: Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch 1900, 1 ff.; Moser 1929, 18 and n. 40, 173-174.

[3] Modena, Archivio di Stato, CPE Minute b.1644/1,2,9, 1r; cf. Moser 1929, 173-174.

[4] McDonald 2014, 20-21; cf. Moser 1929, 37, 40-41.

[5] McDonald 2014, 26-27.

[6] We are grateful to Prof. Artur Rosenauer, University of Vienna, for this information (Red.).

[7] McDonald 2014, 28-33; cf. Moser 1929, 28 and 183.

[8] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60; full text in Moser 1929, 37-38.

[9] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 65; full text in Moser 1929, 38-39.

[10] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60.

[11] “… als zu eyner gezeugnuss, das mich dy Walchen, so doch subtyl synd, auch lobten, und von der musick, so mir got geben hat, auch hyelten”: Letter of 7 February 1518, St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 116; cf. Moser 1929, 40.

[12] McDonald 2014, 6-13; extracts in Moser 1929, 42-44.

[13] See » I. Odengesang.

[14] Modern edition: McDonald 2014.

[15] McDonald 2014, 2-41.

[16] McDonald 2014, 12: “Neque est quicquam (ut in summa referam) Principe magis dignum, quam si quibusque ingenuis artibus præstantes animos amet, foueat, tueatur. Datur enim ex hoc æternæ sibi memoriæ occasio. Hoc diuus Maximilianus, cum in alijs, tum in Paulo cognouit.”

[17] McDonald 2014, 34; cf. Moser 1929, 67.