Hofhaimer and Joachim Vadianus

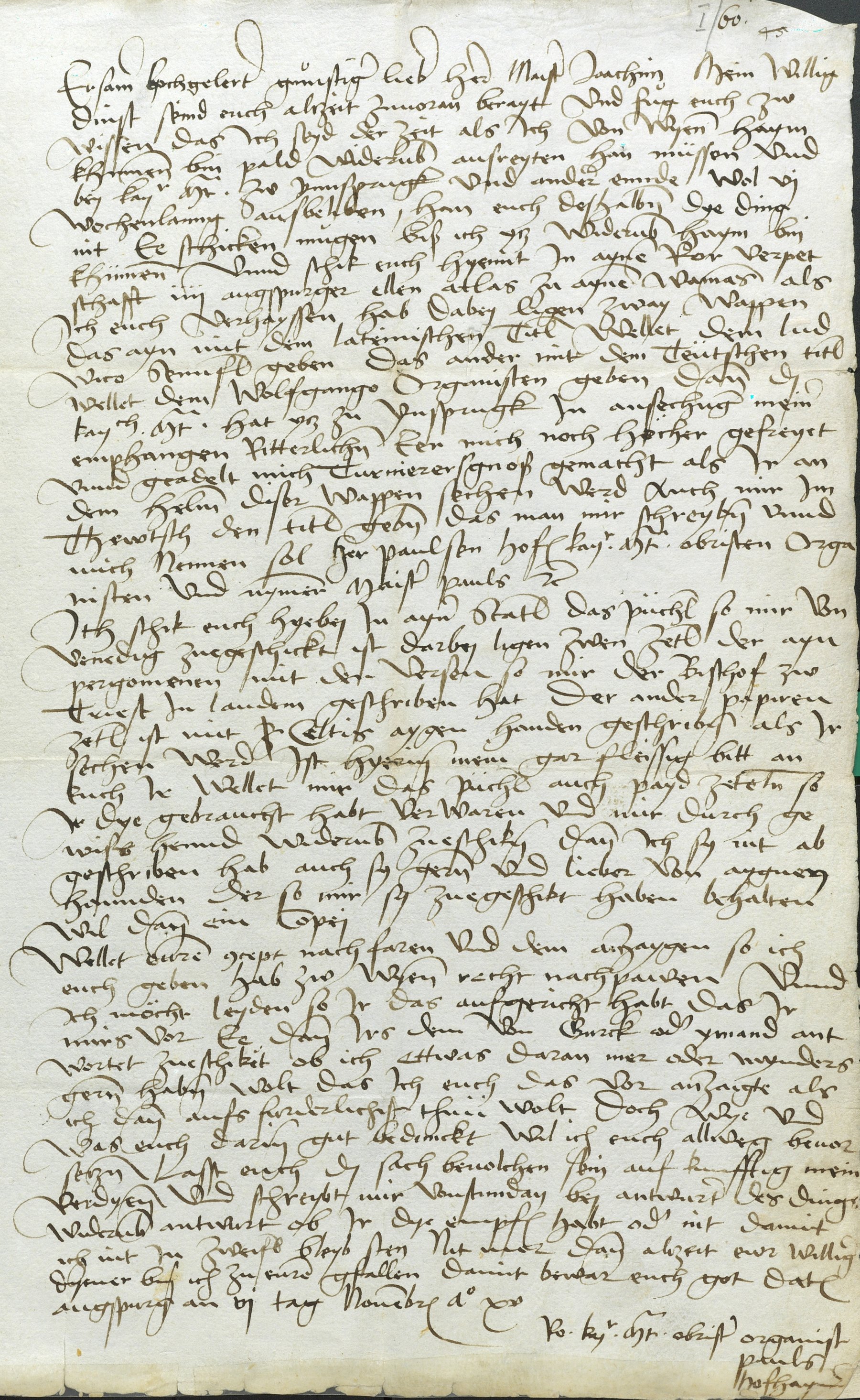

One literary figure with whom Hofhaimer cultivated a particular relationship was Joachim Vadianus, Conrad Celtis’ successor as professor of poetry at Vienna (» I. Innsbruck court). Amongst the hundreds of letters Vadianus preserved were nine from Hofhaimer. The first of these was written on 6 November 1515 ( » Abb. Hofhaimer’s letter to Vadian).[8]

Abb. Hofhaimer’s letter to Vadian

Another letter from Hofhaimer to Vadianus (Nuremberg, 17 April 1516) contains a request that Vadianus should write an elegant Latin panegyric, not so much in praise of Hofhaimer’s musicianship and character as of music itself (“mir ze eren und lob ze machen in Latein, […] zu zyr der loblichen khünst musica mer dann meiner person halb”).[9] Hofhaimer’s insistence that Vadianus should write his panegyric in that language rather than in German says much about the identity of those he hoped to impress. But the requested letter was intended to be useful as well as flattering. Hofhaimer realised that his patron Maximilian was not going to live for ever, and that he might need to present his credentials soon to a new potential patron. Hofhaimer’s instinct was sound. Soon after Maximilian’s death in 1519, his successor Charles V dismissed the entire court chapel, and all its members were sent in search of new patrons.

Already in his first letter to Vadianus of 6 November 1515, Hofhaimer wrote that Maximilian had recently bestowed yet another honour upon him, that of “jousting companion” (turnierersgnoß), and had decreed that from thenceforth, “one should write to me and address me as ‘Herr Paul Hofhaimer, chief organist to his Royal Majesty,’ and no longer as ‘Master Paul.’”.[10] He also sent two copies of his coat of arms, presumably painted on cards or pieces of parchment, which Vadianus was to pass on to Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl) and Wolfgang Grefinger. Hofhaimer also sent Vadianus the poems written earlier by Celtis and Fantin Memmo (brother of Dionisio), the latter “as evidence that the Italians, who are so subtle, have also praised me, and hold in high regard the music that God has given me.”[11]

Vadianus was evidently too busy to carry out Hofhaimer’s request, or put off by his importunity. Hofhaimer bombarded him with increasingly impatient reminders until Vadianus finally delivered the desired letter – two years late.[12] However, there were certain details in the letter with which Hofhaimer was not entirely satisfied, and he sent back a list of suggested improvements. Vadianus, now occupied in the implementation of the reformation in St Gallen, never implemented Hofhaimer’s corrections, despite the further intervention of friends. However, by this stage Hofhaimer had found employment at the court of Matthaeus Lang, cardinal archbishop of Salzburg, one of the late emperor’s most trusted advisors. Lang wanted to transplant something of the splendour of Maximilian’s court to Salzburg, and appointed several musicians previously in the imperial service to work at his cathedral, including Hofhaimer, the singer Wilhelm Waldner, whom he appointed to direct the choir, and the now elderly composer Heinrich Finck, who grumbled that his tasks did not extend beyond training the choirboys at the cathedral.

[8] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60; full text in Moser 1929, 37-38.

[9] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 65; full text in Moser 1929, 38-39.

[10] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60.

[11] “… als zu eyner gezeugnuss, das mich dy Walchen, so doch subtyl synd, auch lobten, und von der musick, so mir got geben hat, auch hyelten”: Letter of 7 February 1518, St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 116; cf. Moser 1929, 40.

[12] McDonald 2014, 6-13; extracts in Moser 1929, 42-44.

[1] Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesarchiv, Hs 208/1, fol. 86v. All English translations in the present article are by Grantley McDonald.

[2] Modena, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio Principi Esteri 1623, b.2/3,2,11, 1r; cf. Ludwig Fökövi, “Musik und musikalische Verhältnisse am Hofe von Matthias Corvinus”, in: Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch 1900, 1 ff.; Moser 1929, 18 and n. 40, 173-174.

[3] Modena, Archivio di Stato, CPE Minute b.1644/1,2,9, 1r; cf. Moser 1929, 173-174.

[4] McDonald 2014, 20-21; cf. Moser 1929, 37, 40-41.

[5] McDonald 2014, 26-27.

[6] We are grateful to Prof. Artur Rosenauer, University of Vienna, for this information (Red.).

[7] McDonald 2014, 28-33; cf. Moser 1929, 28 and 183.

[8] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60; full text in Moser 1929, 37-38.

[9] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 65; full text in Moser 1929, 38-39.

[10] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60.

[11] “… als zu eyner gezeugnuss, das mich dy Walchen, so doch subtyl synd, auch lobten, und von der musick, so mir got geben hat, auch hyelten”: Letter of 7 February 1518, St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 116; cf. Moser 1929, 40.

[12] McDonald 2014, 6-13; extracts in Moser 1929, 42-44.

[13] See » I. Odengesang.

[14] Modern edition: McDonald 2014.

[15] McDonald 2014, 2-41.

[16] McDonald 2014, 12: “Neque est quicquam (ut in summa referam) Principe magis dignum, quam si quibusque ingenuis artibus præstantes animos amet, foueat, tueatur. Datur enim ex hoc æternæ sibi memoriæ occasio. Hoc diuus Maximilianus, cum in alijs, tum in Paulo cognouit.”

[17] McDonald 2014, 34; cf. Moser 1929, 67.