Memorialkultur. Remembering Paul Hofhaimer

Maximilian I’s sense of self-presentation

„Wer ime in seinem leben kain gedachtnus macht, der hat nach seinem tod kain gedächtnus und desselben menschen wird mit dem glockendon vergessen.“

(Whoever does not set up a monument to himself during his life enjoys no memory after his death. Such a man is forgotten as soon as the bell ceases to toll.”)

— Maximilian I, Weißkunig

Emperor Maximilian I understood the power of the arts to promote his image and perpetuate his name. The keyword of his cultural programme was “Gedechtnus”, which may be translated as memory, memorialization or even fame. Maximilian carried out this programme in several ways, to spread his own fame and ensure that he would be remembered in future ages as an outstanding scion of an outstanding family, notable for his power, wealth, political skill and artistic sensitivity. He used portraiture, both during his life and even afterwards. He used performances of music, such as Isaac’s motet Virgo prudentissima, whose text by Georg Slatkonia includes a prayer for the House of Habsburg. He also used liturgical foundations for himself and other members of his family and court. Maximilian was also quick to realize the potential of print in his programme, whether through the production of the chivalric epic » Theuerdank, or through print graphics such as the monumental Triumphzug and Ehrenpforte. Closely involved in the conception and realization of these projects were artists of all kinds attached to the court. Maximilian also used sculpture, notably in his cenotaph in the court church in Innsbruck. The centrepiece of this tomb, first planned in 1502, is an effigy of Maximilian in prayer, mounted upon a sarcophagus and surrounded by twenty-eight figures of his ancestors and role-models, as well as the busts of twenty Roman emperors (» Abb. Cenotaph of Maximilian I). Maximilian was closely involved in the execution of the project over the next seventeen years, although the monument was still unfinished at his death in January 1519, and had to be completed by his heirs. However, the cenotaph stands as lasting witness to Maximilian’s concern for self-presentation and self-memorialization, that is, for his “Gedechtnus”.

Paul Hofhaimer’s way to fame

Though chronically short of funds, Emperor Maximilian I believed that his court should showcase the glory to which his office aspired (» I. Maximilians Monumente). Amongst those employed to create this image of glory and grandeur were musicians, including the trumpet corps, players of loud and soft instruments (» I. Instrumentalkünstler bei Hofe), the court chapel (Hofkapelle), the composer Henricus Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) and the organist Paul Hofhaimer (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik, Kap. Organisten, » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik, Kap. Hofhaimer).

Hofhaimer was born in 1459 in modest circumstances at Radstadt, about seventy kilometres south-east of Salzburg. Although reportedly an autodidact on the organ, he soon attracted attention for his playing, and at the age of nineteen he was employed as organist in the chapel of Archduke Sigmund of Tyrol (» D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck). In the pay records of the Innsbruck court in 1478, Hofhaimer’s name appears as a late addition to the list of four chaplains (probably singers), with the additional note: “his Grace wants to keep him” (“wil jn unser g. h. behalden”).[1] In 1489, Hofhaimer was already so famous that Beatrice of Hungary tried to attract him to her court at Buda: thus she wrote a letter (Buda, 28 September 1489) to Ercole d’Este, Duke of Ferrara, asking him to send his cantor Johannes Martini to Sigmund’s court at Innsbruck to recruit Hofhaimer for her.[2] Ercole’s reply (Ferrara, 24 December 1489) explains that Martini’s mission to Innsbruck had been delayed, because it was known that Hofhaimer was present at the court of King Maximilian, but when the king was coming to the Innsbruck court, Martini, a good friend of Hofhaimer, would immediately be sent there to recruit Hofhaimer for Queen Beatrice’s service.[3] The recruitment came to nothing, however, because Hofhaimer evidently preferred to hitch his fortunes to the new rising star than to risk an uncertain future abroad.

Hofhaimer and the literary and visual arts

At the court of Maximilian, Hofhaimer associated not only with musicians, but also with important literary figures such as Conrad Celtis (» I. Odengesang), Pietro Bonomo and Joachim Vadianus. Indeed, Hofhaimer generally preferred their company to that of other musicians. Normally somewhat abrasive, he was (according to his friend Johannes Stomius) unusually cheerful and relaxed in the company of scholars and poets. However, he had never enjoyed a literary education, and sometimes felt on the back foot with his literary friends, as shown by the tone of his correspondence with Vadianus, in turns ingratiating and demanding. While several of his colleagues, such as the singer Gregor Valentinian or the composer Heinrich Finck, wrote fluent Latin, Hofhaimer’s extant letters are in a workmanlike German. However, several of his literary associates wrote Latin poems and prose pieces in his honour, which he treasured throughout his life, though it is not clear how much of them he understood. Some of these tributes were quite elaborate, such as a small red book containing a letter and poem in Hofhaimer’s honour, sent from Venice by a former student, Dionisio Memmo, along with an embroidered hat.[4]

Hofhaimer’s likeness was preserved by several artists, such as Hans Weiditz (» Abb. Kaiser Maximilians Kapelle), Lucas Cranach and Hans Burgkmair, who depicted him in one of the grand expressions of Maximilian’s “Gedechtnus”, the Triumphzug. (» Abb. Triumphzug, Regal). A poem in Hofhaimer’s honour commissioned by Fantin Memmo mentions a bronze portrait medal of Hofhaimer, which is now lost or unidentified.[5] The subject of the charcoal drawing by Dürer once thought to depict Hofhaimer probably represents a different person.[6]

At the 1515 conference between Maximilian, Sigismund of Poland and Ladislaus of Hungary and Bohemia (» D. Royal Entry), Hofhaimer was honoured by the three monarchs: Maximilian dubbed him a Knight of the Golden Spur, and the other monarchs bestowed similar honours. This occasion was marked by literary testimonials from Philipp Gundelius, Riccardo Sbruglio and Willibald Pirckheimer, and transcripts of these documents were likewise treasured by Hofhaimer.[7]

Hofhaimer and Joachim Vadianus

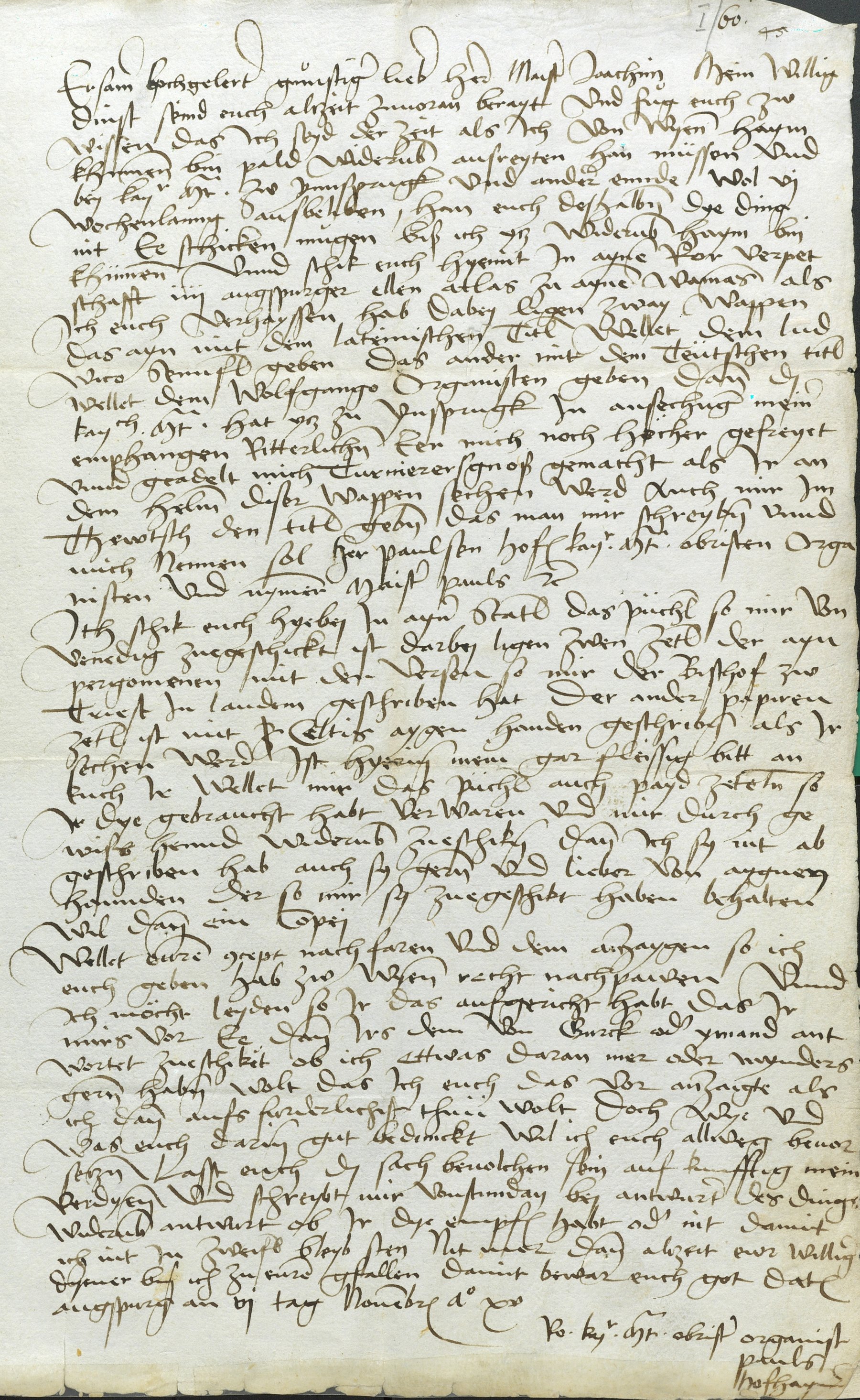

One literary figure with whom Hofhaimer cultivated a particular relationship was Joachim Vadianus, Conrad Celtis’ successor as professor of poetry at Vienna (» I. Innsbruck court). Amongst the hundreds of letters Vadianus preserved were nine from Hofhaimer. The first of these was written on 6 November 1515 ( » Abb. Hofhaimer’s letter to Vadian).[8]

Abb. Hofhaimer’s letter to Vadian

Letter by Paul Hofhaimer to the humanist Joachim Vadian, Augsburg, 6 November 1515 (CH-SGv VadSlg Ms. 30, Brief 60). With permission.For an English translation and further commentary, see » I. SL Life as an emperor’s musician (Helen Coffey).Another letter from Hofhaimer to Vadianus (Nuremberg, 17 April 1516) contains a request that Vadianus should write an elegant Latin panegyric, not so much in praise of Hofhaimer’s musicianship and character as of music itself (“mir ze eren und lob ze machen in Latein, […] zu zyr der loblichen khünst musica mer dann meiner person halb”).[9] Hofhaimer’s insistence that Vadianus should write his panegyric in that language rather than in German says much about the identity of those he hoped to impress. But the requested letter was intended to be useful as well as flattering. Hofhaimer realised that his patron Maximilian was not going to live for ever, and that he might need to present his credentials soon to a new potential patron. Hofhaimer’s instinct was sound. Soon after Maximilian’s death in 1519, his successor Charles V dismissed the entire court chapel, and all its members were sent in search of new patrons.

Already in his first letter to Vadianus of 6 November 1515, Hofhaimer wrote that Maximilian had recently bestowed yet another honour upon him, that of “jousting companion” (turnierersgnoß), and had decreed that from thenceforth, “one should write to me and address me as ‘Herr Paul Hofhaimer, chief organist to his Royal Majesty,’ and no longer as ‘Master Paul.’”.[10] He also sent two copies of his coat of arms, presumably painted on cards or pieces of parchment, which Vadianus was to pass on to Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl) and Wolfgang Grefinger. Hofhaimer also sent Vadianus the poems written earlier by Celtis and Fantin Memmo (brother of Dionisio), the latter “as evidence that the Italians, who are so subtle, have also praised me, and hold in high regard the music that God has given me.”[11]

Vadianus was evidently too busy to carry out Hofhaimer’s request, or put off by his importunity. Hofhaimer bombarded him with increasingly impatient reminders until Vadianus finally delivered the desired letter – two years late.[12] However, there were certain details in the letter with which Hofhaimer was not entirely satisfied, and he sent back a list of suggested improvements. Vadianus, now occupied in the implementation of the reformation in St Gallen, never implemented Hofhaimer’s corrections, despite the further intervention of friends. However, by this stage Hofhaimer had found employment at the court of Matthaeus Lang, cardinal archbishop of Salzburg, one of the late emperor’s most trusted advisors. Lang wanted to transplant something of the splendour of Maximilian’s court to Salzburg, and appointed several musicians previously in the imperial service to work at his cathedral, including Hofhaimer, the singer Wilhelm Waldner, whom he appointed to direct the choir, and the now elderly composer Heinrich Finck, who grumbled that his tasks did not extend beyond training the choirboys at the cathedral.

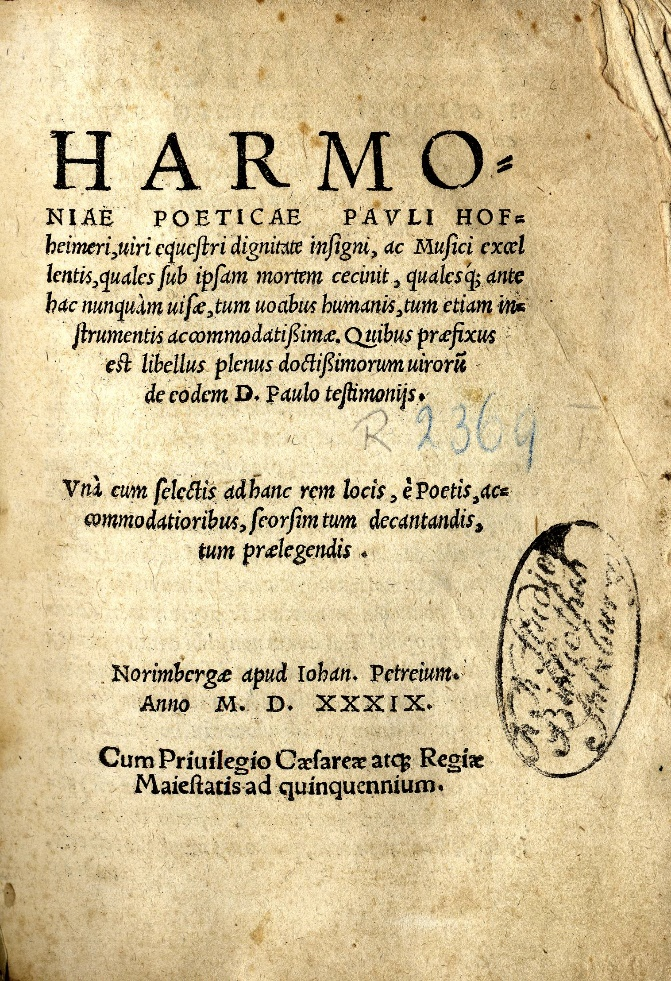

A book in memory of Hofhaimer: the Harmoniae poeticae of 1539

In 1530 a young Bavarian humanist and musician, Johannes Stomius, established a private Latin school at Salzburg. Before long Stomius had become one of Hofhaimer’s intimate circle, and the old man entrusted to him the task of publishing the literary testimonials he had been collecting over the years, in a collection dedicated to Matthaeus Lang. In return, Hofhaimer agreed to compose a series of homophonic settings of poems by Horace, Ovid, Vergil and Prudentius, which were to be used in Stomius’ school. The models for this collection were Celtis’ edition of » Melopoiae (1507), composed by Petrus Tritonius and others (» I. Odengesang), Ludwig Senfl’s » Varia carminum genera (1532) and Sebastian Forster’s » Harmoniae Prudentianae (1533).[13] Given Hofhaimer’s diffidence about his own standing amongst the humanists at court, it is ironic that his last works should have been exercises in that most humanistic of musical genres, the humanist ode-setting. In 1537, while completing his cycle of settings of Prudentius, Hofhaimer died. Once a legal wrangle over the fate of Hofhaimer’s papers had been settled, the collection » Harmoniae poeticae was printed at Nuremberg by Johannes Petreius in 1539.

The resulting publication is really two books in one.[14] The larger part of the book comprises Hofhaimer’s ode settings (» Hörbsp. ♫ Iam satis terris und » Hörbsp. ♫ Maecenas atavis), to which Stomius added another nine by Senfl, one by Hofhaimer’s assistant organist Gregor Peschin, and one by an anonymous composer, perhaps Stomius himself. The ode settings are preceded by thirty-seven pages of poems and letters collected over the years by Hofhaimer, the so-called libellus, introduced by Stomius’ dedication of the whole work to Matthaeus Lang .[15] The keynote of Stomius’ dedication is “memory”:

“[…] what is left to commend this great man and to promote his immortal fame, than to recall in the memory of men the lively powers of his mind, to examine his talents and evaluate them carefully? These cannot be appreciated anywhere more clearly than in his offspring, that is, in his writings and in the success of his students. […] It seemed a great shame to me that, either through ignorance or the ingratitude of the age, people gave no more thought to Paul’s memory, the one thing he most cared about. For this reason I wanted to save something, if only a shadow, of his memory from oblivion.”

Stomius presents memory as something that is constantly threatening to be lost. He reminds Lang that “if the lawyer Georg Teisenperger had not been so diligent about preserving the memory of the deceased, those papers would have perished entirely.” Stomius also presents a conscious reminiscence of Hofhaimer’s attitude to the question of fame and memory:

“I often remember him saying that he, already on the threshold of old age, was not motivated by the desire for glory, but since the writings of those great men had been preserved, he was reluctant to let them perish, not so much for his own sake as for that of Germany as a whole, so that we might have some means to defend ourselves against those foreigners who accuse us of being ignorant in this art.”

In the light of Hofhaimer’s correspondence with Vadianus, his protestations cannot but strike the reader as disingenuous.

Amongst the earliest of the texts in the libellus are those by Celtis (who died in 1508) and Fantin Memmo, evidently written not long after his brother Dionisio’s return to Venice from his apprenticeship under Hofhaimer in 1507. Towards the end of the collection are also several elegies. Surprisingly, some of these were written in the second decade of the sixteenth century, more than twenty years before Hofhaimer’s death. At least one (possibly two) was written in 1513 by Vadianus, who describes himself as “an admirer of [Hofhaimer’s] talent and skill.” Another, by Riccardo Sbruglio, was written after Hofhaimer’s elevation to the peerage in 1515, but before Maximilian’s death in 1519. Sbruglio also contributed a lament on the death of Hofhaimer’s second wife Margarete, who died in 1518, and probably also an epitaph to Hofhaimer’s father, which concludes: “Why is Paul remembered with such reverence on earth? He was the invincible master of harmony.” (Again this epitaph touches upon the theme of remembrance, “Gedechtnus”.) The latest poems in the libellus are laments written after Hofhaimer’s death, including two by Stomius, one by one of his students, and two by the Salzburg statesman Hieronymus Anfang. The contents of the libellus were thus written over the course of thirty years or more, and represent a collection of texts carefully selected – and in some cases actively solicited – to project a carefully cultivated image of their subject, Hofhaimer.

The » Harmoniae poeticae thus serves not only as a collection of music, but equally as an analogue in print to Maximilian’s cenotaph at Innsbruck, an artistic memorial planned by its subject over many years, and brought to completion after his death through the force of his personality and the loyalty of those who survived him. In his panegyric on Hofhaimer, Vadianus had written that “there is no truer mark of a prince than if he loves, fosters and protects those endowed with exceptional talent in the honest arts, for this is the way for them to achieve eternal remembrance. The Emperor Maximilian has come to realise this with others, but especially with Paul [Hofhaimer].”[16] It is understandable that Hofhaimer, whose artistic excellence reflected glory on his patron, should have wanted to create a similar monument to himself, mindful of Maximilian’s injunction that a man should take care that his memory last longer than the final stroke of the bell at his funeral. Just as Maximilian had been involved in the creation of his own cenotaph for some seventeen years before his death, Hofhaimer collected literary testimonia in his own honour for over three decades. The similarities between Maximilian’s cenotaph and Hofhaimer’s Harmoniae poeticae are made particularly clear in one of Vadianus’ epitaphs to the composer; here the poet imagines Hofhaimer addressing the reader after his death, concluding with an artful literary allusion to Ovid:

Attamen, ut cernis, iaceo sine luce cadaver,

Marmoreusque premit membra sepulta lapis.

Tu, si nomen amas Pauli, sique ars tibi cordi est,

Qua valuit, vivo flumine saxa riga.

Manibus et functis vitam requiemque precator

Caetera de nobis fama superstes erit.[17](But now, as you see, I lie here, a corpse shut up in the darkness,

And a marble slab weighs down my buried limbs.

If you love the name of Paul, and if you treasure the art

In which he excelled, shed a tear upon this stone.

Pray for the souls of the departed, for their eternal life and their rest;

Of all we are, only our reputation shall survive.)The survival of Hofhaimer’s reputation

Hofhaimer’s reputation of course survived for centuries, although it is questionable whether he would have enjoyed all its later manifestations. The 19th-century plaque on his Salzburg dwelling (» Abb. Hofhaimers Gedenktafel) suggests a connection between “Gedechtnus” and place, which is already envisaged in the very idea of the epitaph: the famous man is best remembered in the place where he actually is (or was). Thus the visitor to Salzburg who stands in front of the musician’s former house in the Pfeifergasse is in reality paying respect to a place of life – and death.

[1] Innsbruck, Tiroler Landesarchiv, Hs 208/1, fol. 86v. All English translations in the present article are by Grantley McDonald.

[2] Modena, Archivio di Stato, Carteggio Principi Esteri 1623, b.2/3,2,11, 1r; cf. Ludwig Fökövi, “Musik und musikalische Verhältnisse am Hofe von Matthias Corvinus”, in: Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch 1900, 1 ff.; Moser 1929, 18 and n. 40, 173-174.

[3] Modena, Archivio di Stato, CPE Minute b.1644/1,2,9, 1r; cf. Moser 1929, 173-174.

[4] McDonald 2014, 20-21; cf. Moser 1929, 37, 40-41.

[5] McDonald 2014, 26-27.

[6] We are grateful to Prof. Artur Rosenauer, University of Vienna, for this information (Red.).

[7] McDonald 2014, 28-33; cf. Moser 1929, 28 and 183.

[8] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60; full text in Moser 1929, 37-38.

[9] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 65; full text in Moser 1929, 38-39.

[10] St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 60.

[11] “… als zu eyner gezeugnuss, das mich dy Walchen, so doch subtyl synd, auch lobten, und von der musick, so mir got geben hat, auch hyelten”: Letter of 7 February 1518, St Gallen, Kantonsbibliothek, Vadianische Sammlung ms 30, nº 116; cf. Moser 1929, 40.

[12] McDonald 2014, 6-13; extracts in Moser 1929, 42-44.

[13] See » I. Odengesang.

[14] Modern edition: McDonald 2014.

[15] McDonald 2014, 2-41.

[16] McDonald 2014, 12: “Neque est quicquam (ut in summa referam) Principe magis dignum, quam si quibusque ingenuis artibus præstantes animos amet, foueat, tueatur. Datur enim ex hoc æternæ sibi memoriæ occasio. Hoc diuus Maximilianus, cum in alijs, tum in Paulo cognouit.”

[17] McDonald 2014, 34; cf. Moser 1929, 67.

Herrmann 1997 | Hirzel 1909 | Hofhaimer 1539 | Moser 1932/1933 | Näf 1945 | Reutter 1997 | Sallaberger 1997 | Schuler 1995

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Grantley McDonald: „Memorialkultur. Remembering Paul Hofhaimer“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/memorialkultur-remembering-paul-hofhaimer> (2017).