Lute Intabulations by Adolf Blindhamer

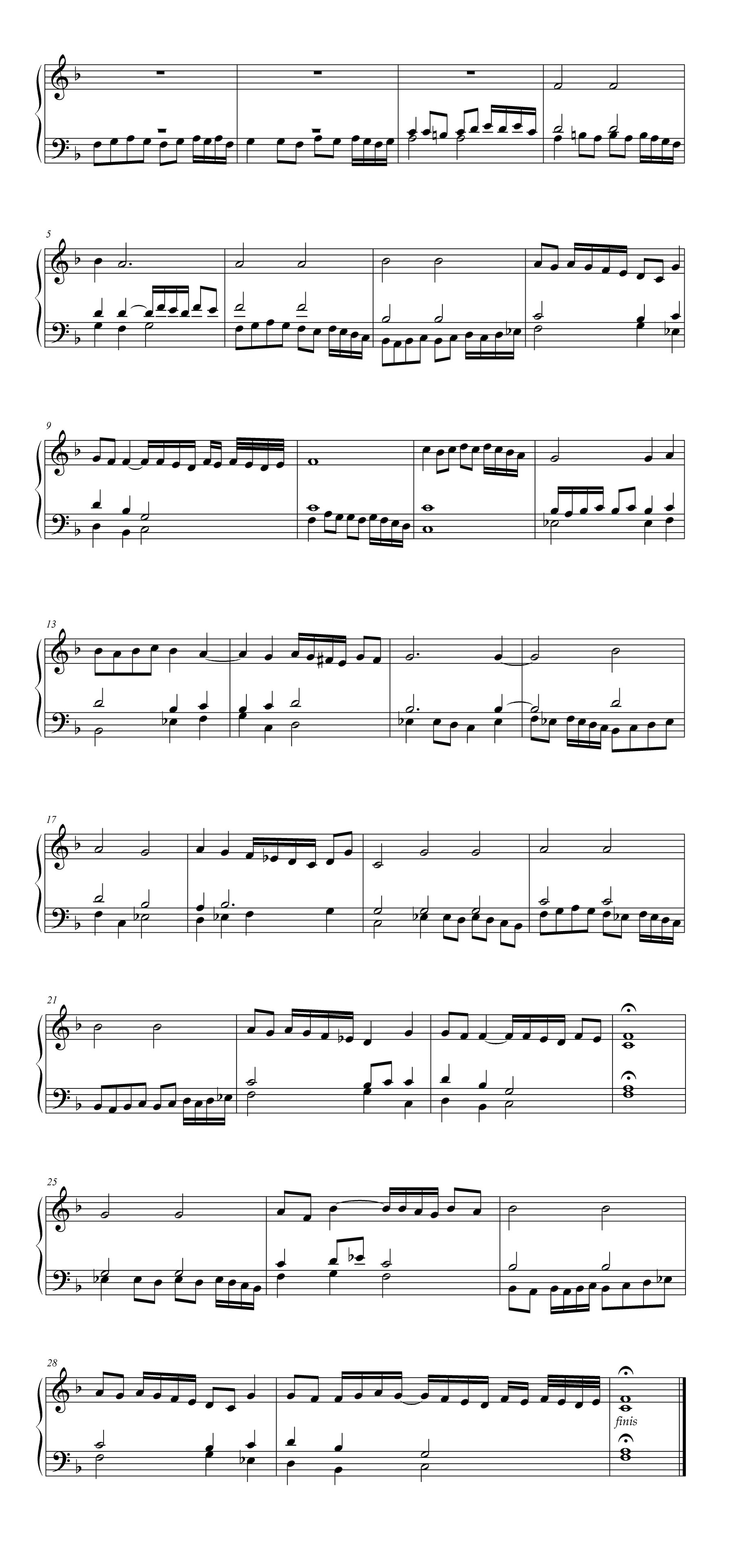

A slender manuscript with lute intabulations by Blindhamer (» A-Wn Mus. Hs. 41950), with an estimated date of around 1525, is not only one of the earliest surviving sources of lute music but also almost the only source from this period that records more complex music by a professional player rather than didactically simplified music for beginners.[37] It contains a long praeambulum (a fantasia-like free form), followed by instrumental pieces designated here as “Mutetae”, as well as intabulations of vocal compositions and some dance pieces. Besides Blindhamer himself, several composers are named: Josquin Desprez, Paul Hofhaimer (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » C. Paul Hofhaimer), Heinrich Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac), and Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl). Except for Josquin, these musicians were closely associated with Maximilian. This closeness perhaps also explains the existence of a unique piece, a “Muteta mester paulus hofhamer” (» Notenbsp. Muteta mester paulus hofhamer), which is only preserved in this manuscript.

The title carries the addition “mit 3 stymen” (with 3 voices) meaning that three voices were considered in the intabulation (other intabulations in the source even mention four voices, which indicates the special skill of both the intabulator and the player in preserving and playing, in the lute version, multiple contrapuntal voices). Musically, the virtuosic embellishments, called “coloration” at the time, stand out. Blindhamer’s presumed student Hans Gerle describes his playing as follows:

“Es hat auch gedachter Adolff (damit sein kunst vnd schickligkait erweittert werde) diese art gefürt / die dann alle Künstner der Musick vnd derselben Instrumenten haben sollen / wenn er bey verstendigen der Musica / oder vor berümbten Syngern geschlagen / hat er sich gleichwol zuuor in seinen Preambeln dermassen hören lassen / das sein geradigkait vnd kunst gewaltig erschinen ist / zusampt dem / so er zu einem gesatzten stücklein gegriffen / hat er das erstlich / wie es in noten gestanden / mit wenig Coloraturen / zum andern mit wolgestelten leuflein geziert / vnd zum dritten durch die Proportion geschlagen vnd volfürt / Vnd doch einer solchen gestalt / damit der süssigkait vnd vollkomenheyt des gesangs nichts benomen worden ist.”[38]

(Adolf (so that his art and skill may be extended) practiced this way, which all musicians and players of these instruments should follow. When he played before knowledgeable musicians or renowned singers, he first let himself be heard in his preludes, so that his precision and artistry appeared mightily. Additionally, when he played a written piece, he first played it with few embellishments, then adorned it with well-placed runs, and finally played it through proportional variations, without taking away the sweetness and completeness of the song.)

After a prelude, which served both to tune the instrument and to attune the listeners and included virtuosic passages, Blindhamer played a written composition, such as the intabulation of a polyphonic vocal piece. The piece was played first with few embellishments, followed by a version with many runs and elaborations. Finally, the piece could be rhythmically varied in another repetition, without distorting the underlying composition. Remarkable is the repeated, always varied performance of usually short pieces mentioned here.

The piece by Hofhaimer, preserved only as a lute intabulation, highlights the significant gaps in the musical transmission that must be expected, as this is certainly not an original composition by Hofhaimer for the lute, but only an adaptation for this instrument. Such gaps are notable in the surviving music of Paul Hofhaimer. Although he was employed for life as an organist at the Habsburg court in Innsbruck in 1480, surprisingly little of his liturgical organ music has been preserved, even though this was the basis of his activity and fame. The elevation to knighthood in 1515, so important to him, took place in Vienna during the double wedding of Maximilian’s grandchildren. Following the ceremony, the imperial trumpeters played a fanfare, and the imperial chapel sang the Te Deum, and “in Organis Magister Paulus, qui in universa Germania parem non habet, respondit” (on the organ responded Master Paul, who has no equal in all of Germany).[39] This “responding” describes the so-called “alternatim practice,” in which the versets of a liturgical chant are alternately sung and played on the organ. The organist based his part on the liturgical tenor and demonstrated his skill by how artfully he adorned the cantus firmus. Only two of Hofhaimer’s organ settings have survived, perhaps recorded by his students—Hofhaimer himself probably extemporised them. His student Hans Buchner describes various methods of such chorale settings (even using the example of the Te Deum), but Hofhaimer’s practice also emerges from the two surviving organ pieces. Especially in the Recordare, based on the liturgical tenor, which was also appended to a Salve Regina like a hymn, the varied ways of handling the cantus firmus are evident, sounding in different voices and contrapuntal techniques in the three-voice setting.[40]

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; facsimile and description in Kirnbauer 2003. For lute tablatures of the next generation from the southern German-speaking area, see » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] See Moser 1966, 26 and 182, footnote 35.

[40] See Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; see also » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

[1] For information on the Triumphzug, its different versions, and its complex history, see Appuhn 1979 and Michel/Sternath 2012; on its significance for Maximilian, see Müller 1982; on the relationship between depiction and reality, see Polk 1992; The quotation comes from the earliest surviving formulation of the iconographic program of the Triumphzug in 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (quotation from the Augsburg Baumeisterbücher of 1491, the council’s account books for income and expenses).

[5] See Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] See Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Quoted in Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] See Schwindt 2012.

[10] She received 50 guilders “zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung” (for her maintenance and living) in June 1520 when the court chapel was dissolved after Maximilian’s death; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Such as “Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher”, who were expressly paid for their services “bei Tanz” at the 1491 carnival; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] For a compilation of music-related illustrations, see Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] See Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[16] Polk 1992, 86 (with references from Augsburg archives).

[17] See Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] See Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (including the following).

[20] According to payments in the Augsburg (D-As) Baumeisterbuch 103 (1509), fol. 24v, and 104 (1510), fol. 28; kindly communicated by Keith Polk.

[21] See Jahn 1925, 10 ff., and Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] See Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] See the letter from Paul Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadian on May 14, 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So the wording in the formulation of the iconographic program in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] See Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, title page of the tenor partbook; for dating, see Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] See Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] See Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[36] Senn 1954, 26, referring to Maximilian’s letter in A-Wn, Cod. 10100b, fol. 15r–v, edited in Kraus 1875, 39. I owe the correction in this context to Grantley McDonald, who also drew my attention to the ‘Lauerpfeif’ (KHM Vienna, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, A 74), a cannon with two pipes attached to the side of the gun barrel that can be used to produce whistling sounds; see Krammer 2025.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; facsimile and description in Kirnbauer 2003. For lute tablatures of the next generation from the southern German-speaking area, see » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] See Moser 1966, 26 and 182, footnote 35.

[40] See Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; see also » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Recommended Citation:

Martin Kirnbauer: “Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).