Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I

Court Music and Representation

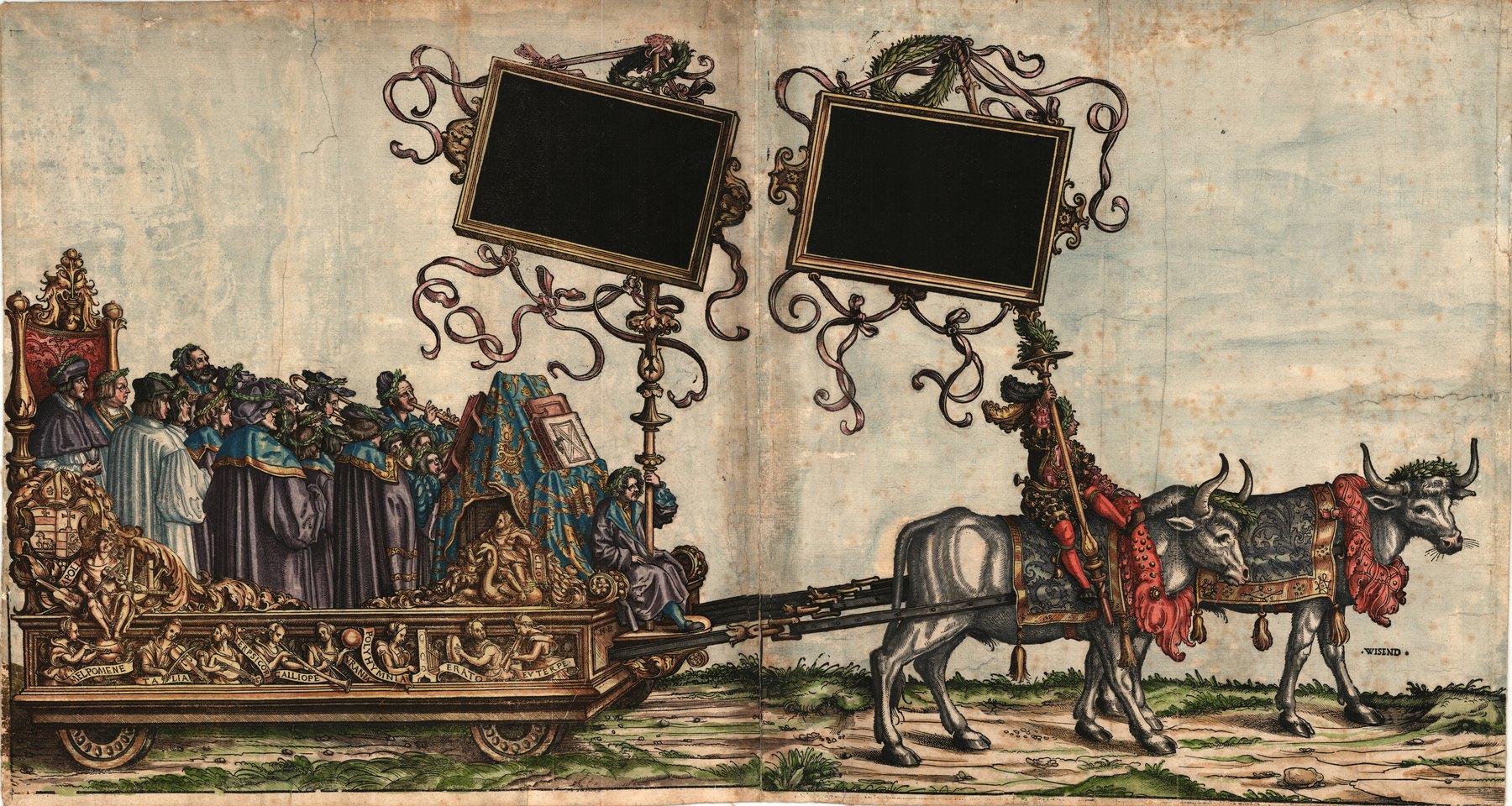

The wealth and extent of the musical representation apparatus of Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) is vividly illustrated in the woodcuts of the so-called Triumphzug. However, it should not be forgotten that this ambitious and costly visual project is not a realistic depiction of his court chapel but rather a highly idealized vision “zu lob vnnd Ewiger gedächtnüs” (for praise and eternal remembrance) of the reputation-conscious monarch.[1] The image frieze, which in its assembled state is over 100 metres long, includes, in addition to the carriage with the actual court chapel (titled “Musica Canterey” with the chapel master Georg Slatkonia and singers), four other carriages with musicians, not to mention a considerable number of trumpeters and drummers, “Burgundisch pfeyffer” (Burgundian pipers), as well as pipers and drummers, who are all represented in the procession. The more modest historical reality of Maximilian’s musical apparatus is reflected in the account books, such as the inventory on the occasion of the dissolution of the court chapel in 1520 after Maximilian’s death: Here, there are a total of thirteen “Trumetter vnd paugker” (trumpeters and timpanists), nineteen adult singers, about twenty boys as “Discantisten” (trebles), and one “organista” in the “Capellen oder Cannthorey” (chapel or cantorey); among the other ranks, only one “geyger” (string instrument player) is listed.[2] This discrepancy is explained by the different functions of the musicians: The singers were needed for worship services, while the trumpeters and drummers primarily served as a visual and acoustic heraldic sign and were considered the much-cited “Ehr und Zier” (honour and ornament), an indispensable status symbol of the ruler.[3] The other musicians, however, primarily served the so-called “Kurzweil” (diversion) and were only indirectly representative, for example at imperial diets or as musical ambassadors, when they performed, dressed in the ruler’s livery, in imperial cities and at princely courts, for example as “zwayen siner Maiestat Luttenschlager” (two of His Majesty’s lutenists), receiving substantial monetary gifts for their performances.[4] Venetian envoys who met Maximilian in Strasbourg in 1492 reported the honour they received through the visit of the royal musicians to their quarters: fourteen trumpeters with large drums appeared, as well as pipers, drummers, and lutenists. Additionally, three brothers with their father, who played a claviorganum (a keyboard instrument that combines organ and harpsichord), lute, and fiddle.[5] This artistic family enterprise is also explicitly described as belonging to the court, although they have not yet been documented archivally.

The representative function—more so than his own musical needs—primarily explains Maximilian’s interest in associating outstanding instrumental musicians with his court. It is well known that music and musicians at a court were considered an important part of the ruler’s glory.[6] In this sense, reports of Maximilian’s special love for music can be understood as part of a ruler’s praise, as can be read in the biography of his humanistically trained personal physician Johannes Cuspinianus:

“Musices vero singularis amator, quod vel hinc maxime patet, quod nostra aetate musicorum principes omnes in omni genere musices omnibusque instrumentis in ejus curia veluti in fertilissimo agro succreverint, veluti fungi unâ pluviâ nascuntur”[7]

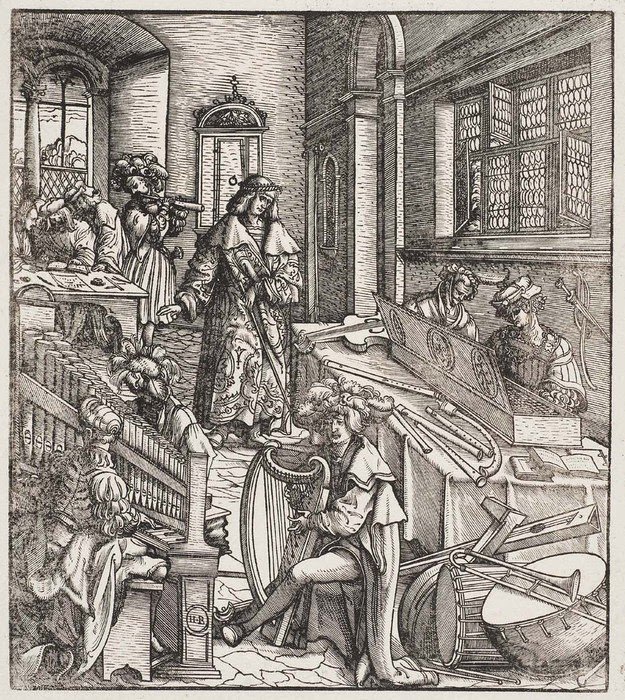

(He was a unique lover of music, which is especially evident from the fact that all the great masters of music in our time in every genre and on all instruments flourished at his court, as if on the most fertile soil, just like mushrooms that shoot up after a single rain-shower.)The often-cited passage in the epic poem Weißkunig (The White [or Wise] King), an ambitious publication project comparable to the Triumphzug, is to be understood in a similar way. Here, it is reported how the young king, an idealised alter ego of Maximilian, establishes a “Canterey” (chapel), “mit ainem sölichen lieblichn gesang, von der menschen stymm wunderlich zu hören, vnd söliche liebliche herpfen, von Newen wercken, vnd mit suessem saydtenspil, das Er alle kunig übertraff, vnd Ime nyemandts geleichen mocht, sölichs unnderhielt Er, fur vnd fur, das ainem grossen furstenhof geleichet, […]” (with such sweet singing, wonderful to hear from human voices, and such lovely harps, new instruments, and sweet string music, that he surpassed all kings, and none could compare to him. Such music he maintained continuously, as befits a great princely court).[8] In the accompanying illustration, the Weißkunig can be seen amidst instrumental musicians, literally giving them the “beat” with a long staff (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33).[9] Interpreted differently, the illustration shows that all music at the court traces back to and references its actual centre, the ruler.

The Musicians at the Court of Maximilian I

Considering the long list of instrumental musicians recorded in Maximilian’s account books—including, by the way, a female musician, “Lucia Torerin Lauttenslagerin” (lutenist) although she did not hold a fixed position[10]—the trumpeters and drummers (who formed an ensemble) made up the largest group (» H. Zugtrompete), followed by trombonists (» H. Posaune) as well as pipers and drummers (» H. Einhandflote & Trommel). These latter two groups also formed an ensemble responsible for both military duties and dance accompaniment.[11] The trombonists are occasionally mentioned alongside the trumpeters, but could also perform with other musicians. Additionally, several lutenists are listed, who played both solo and in ensemble. Finally, there is always an organist recorded. For many years this was Paul Hofhaimer (»C. Organs and organ music; » I. Paul Hofhaimer), who was generally associated with the “Canterey” (cantorey) or “Capellen” (chapel), that is, the singers.

Pipers and Drummers

In the representative arrangement of the Triumphzug, the procession begins with “Pfeyffer vnd Trumlslager” (pipers and drummers), among whom “Annthonj von Dornstet” is prominently mentioned in the written program.[12] Besides the military function of this ensemble, which gave signals in battles and marches, the accompanying verses also mention the piper’s role in providing “kurtzweyl” (entertainment). This primarily refers to playing for dances at the court (»H.Einhandfloete & Trommel), as seen in numerous images in Freydal, another book project by Maximilian I with an autobiographical account of his journey to his wedding with Mary of Burgundy.[13] A good impression of the importance of these musicians to Maximilian is conveyed by a letter of 1495, in which he urgently requests the release of musicians detained in Worms due to unpaid debts and their immediate dispatch to Milan, “dann wir tanzen hie stetige an ain Pfeifer und auf ainer Stelzen” (as we dance here constantly without a piper and on one chopine shoe).[14]

“Musica Lauten und Rybeben”: Lutes and String Instruments

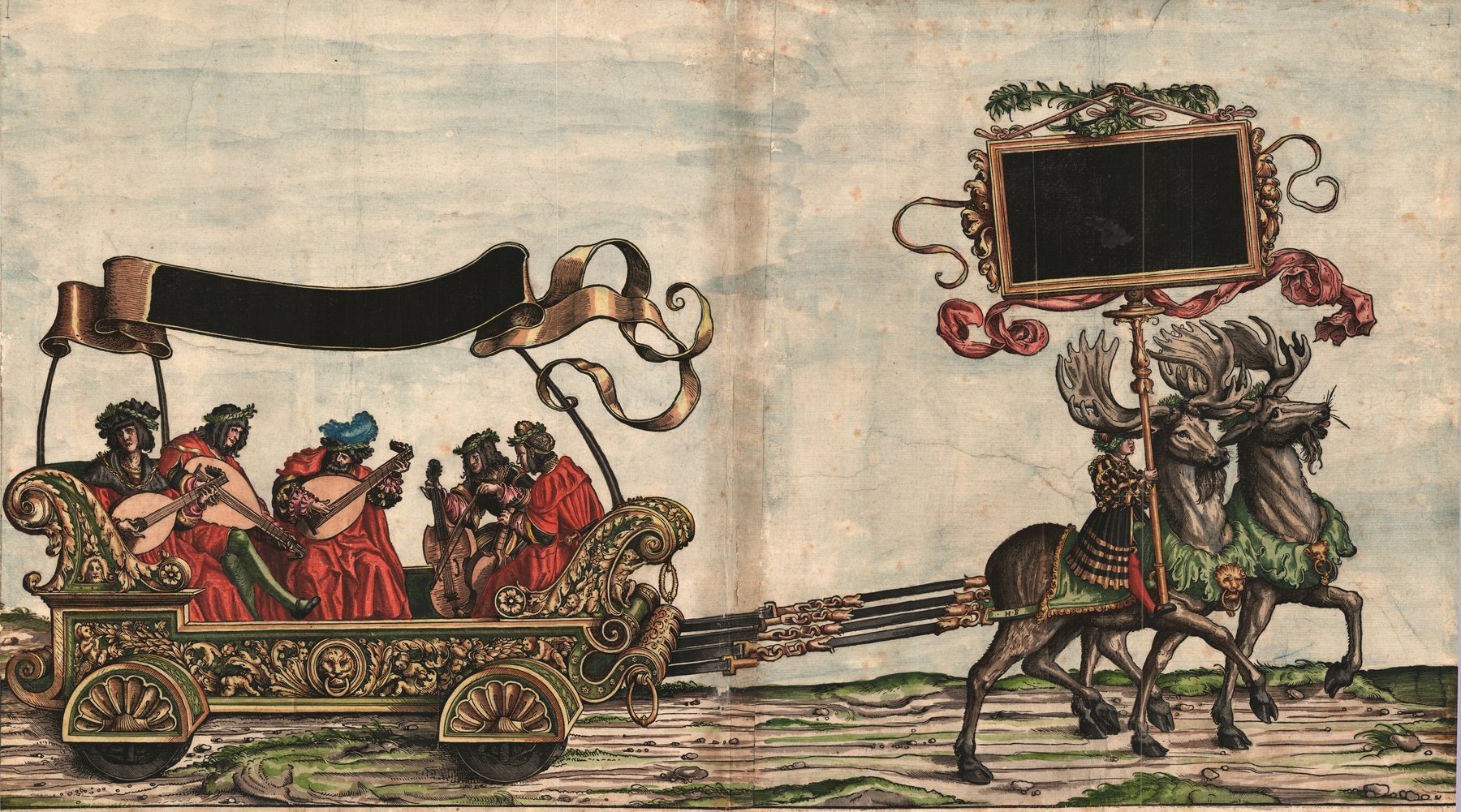

In the Triumphzug, following soon after the pipers and drummers, the first musicians carriage is shown, titled “Musica Lauten und Rybeben” (Music: lutes and viols) (» Abb. Triumphzug Lauten), on which five musicians are seated, playing three lutes of different sizes and two larger string instruments. These vertically-held instruments can be described as violas da gamba (H.»Renaissancegambe), known at Maximilian’s court as “Ribebe.” This name is derived from the Arabic rebab (or rabāb) and was used primarily in Italy to refer to a larger string instrument. In any case, it is a loan-word, associating the instrument with foreign origins; however, these instruments differ visually from contemporary Italian images. The “Maister,” or the most distinguished of these musicians, is a certain Artus, presumably the older man in the middle of the carriage. This Artus was actually named Albrecht Morhanns, but he was known as Artus von Enntz Wehingen.[15] Born around 1460, he participated in the famous pilgrimage of Baron Werner von Zimmern to the Holy Land in 1483 as a serf, charged with the duties of a barber and lutenist. Maximilian specifically sought to bring him into his retinue due to his exceptional skills as a lutenist, and in 1489, he was freed from serfdom “seiner kunst schickligkeit und genediger neygung willen” (for the sake of his artistic skill and gracious inclination). Subsequently, Artus is documented as “des Rö. kunigs luttesschlaher” (the lute player of the Roman king), often mentioned alongside a second lutenist with whom he apparently performed as a duo.[16] Such a lute duo is well-documented in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries: one player, known as the “tenorista,” played the tenor or provided a sonic framework (for example, of a song, motet, or basse danse), while the other player, the “diskantista,” improvised over it. A hallmark of this playing style is the use of a plectrum, such as a quill, enabling particularly swift and virtuosic runs.[17]

One of the younger musicians on the same carriage could be Adolf Blindhamer (c. 1480–before 1532), who is documented as a lutenist at the court for the first time in 1503.[18] He retained the title “lawtenslaher kays. Mt” (lutenist to His Imperial Majesty) until the death of Maximilian, although in 1514 he was received as a citizen in Nuremberg to teach “den Jungen auf der lauten und anndern Instrumenten” (the young people on the lute and other instruments). Particularly significant is that a manuscript with compositions and arrangements for the lute by Blindhamer has been preserved, providing insight into the concrete music of the lutenists at Maximilian’s court (» Kap. Lute Intabulations by Adolf Blindhamer). This reveals a polyphonic playing style, where multiple voices are plucked simultaneously with the fingers.

The lutes and “Rybeben” were probably played by the same musicians, since the lute and viol were long considered related or similar instruments, as evidenced by the earliest instructional books for these instruments, such as those by Hans Judenkünig (Vienna 1523) or Hans Gerle (Nuremberg 1532), and as suggested by the similar setup of the strings, frets and tuning. It has been speculated that the mention of three to four “geyger” of the emperor (first noted in 1515) refers to an ensemble of such viols, as documented at Italian courts at the same time.[19] However, this must remain speculative, as besides the vague designation “kay. Mt. Geygern” (geyger to His Imperial Majesty) only the names of the players are known (Caspar and Gregor Egkern, Jorigen Berber, and Heronimus Hager), but nothing about their instruments. Caspar Egkern appears a few years earlier also as “Kay. Mayt. busaner” (trombonist to His Imperial Majesty) or “Kay Mayt pfeyffer” (piper to His Imperial Majesty), so he was not limited to a specific instrument.[20]

“Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen krumphörner”: Shawms, trombones und crumhorns

Hans Neuschel (c. 1470–1533) is named as the “Maister” of the second musicians carriage in the Triumphzug, “Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen, krumphörner” (Music: shawms, trombones und crumhorns) (» Abb. Triumphzug Bläser). He was never a permanent member of Maximilian’s court chapel, but worked as a trumpet maker and city piper in Nuremberg.[21] Although Maximilian evidently valued him and often requested him from the Nuremberg council as a musician, Neuschel himself was not entirely happy about this honour, as the travels to Maximilian, which sometimes occupied him “lenger dann jar und tag” (longer than a year and a day), caused him to neglect his other customers: “das ihm dadurch sein werkstat ganz erniderlegt und er in seinem abwesen von seinem handwerk feiern, dadurch seine kunden und kaufleut verlieren und des, so er mit solchem seinem handel verdienen und erarbeiten mog, empern und allein vil schulden, darein er hievor, als er kais. maj. ein zeitlang nachgeraist sei, muss gewarten” (because his workshop was completely idle and he had to abstain from his craft in his absence, thereby losing his customers and traders, and forgoing the income he would otherwise earn, and expecting only debts because he had to follow the emperor).[22] Trombonists like Neuschel, or Hans Stewdl (or Steydlin), who is mentioned elsewhere in the Triumphzug, were specialists who performed with the singers on special occasions. For example, it is noted that during the Imperial Diet in Trier in 1512, the emperor had “Misse gehoret, die ist discantirt. Darinn mitl zincken vnd basunen geblasen” (heard Mass, which was sung in discant [polyphony]. Therein, cornets and trombones played).[23] This suggests that one or more trombones played the lower parts of a vocally performed polyphonic Mass while a cornet player played the upper part and presumably improvised. It is also conceivable that a trombonist played a new or additional contratenor part. (A possible impression of such a “loud” ensemble is provided by » Hörbsp. ♫ La la hö hö.)

This exact situation is depicted in the Triumphzug on the carriage of the “Musica Canterey” (Music: chapel) (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei) where alongside the singers, a cornet player and a trombonist can be seen. According to the pictorial programme, Augustin Schubinger and Hans Stewdl are depicted here. Schubinger (» G. Augustin Schubinger ) was evidently the specialist for cornet playing in his time (»H. Zink / Cornett). He came from an Augsburg city piper family that produced many outstanding wind players.[24] Augustin was probably born around 1460 and is documented as a city piper in Augsburg from 1477. Temporarily also in the service of the Margrave of Brandenburg and Maximilian’s father, Frederick III, he can be traced between 1489 and 1493 in northern Italy and especially in Florence, where Henricus Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) also worked. After the fall of the Medici, Augustin returned to Habsburg service; again, in a certain parallel to Isaac, who returned to Maximilian’s court a few years later. Schubinger seems to have gradually specialized in the cornet, as at the beginning of his career he is still referred to as a “pfeifer,” generally understood to be a professional musician and player of wind instruments, then as a “busauner” (trombonist), indicating a certain specialisation in contratenor parts, and also as a lutenist. This shows that instrumental musicians were generally proficient in several instruments. In the employment contract of Augustin’s younger brother Ulrich with the Archbishop of Salzburg in 1519, it is stated that he serves his new lord “mit ribeben, geygen, pusawn, pfeiffen, lawtten und annders instrumentn in der musiken, darauf er etwas khann” (with viols, fiddles, trombones, pipes, lutes, and other instruments in music, on which he can play).[25] With the exception of keyboard instruments, all conceivable wind, plucked, and string instruments are listed here, which were quite evidently mastered and probably played.

“Musica Rigal vnd possetif”: Keyboard Instruments

The third musician carriage in the Triumphzug, titled “Musica Rigal vnd possetif” (Music: regal and positive organ) (» Abb. Triumphzug Regal) features only one musician: Paul Hofhaimer (1459–1537; » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » C. Paul Hofhaimer). The image also includes a realistic detail, a bellows operator, who operates the bellows of the positive organ, without whom any organ would remain silent until the invention of the electrically driven air supply. Behind Hofhaimer, more keyboard instruments can be seen hidden in transport cases (according to the text, one is supposed to be a regal, the other could be a clavicytherium—a keyboard instrument with upright strings and a plucking mechanism like a harpsichord). Hofhaimer had been associated with the Habsburgs as an organist since his youth, serving Maximilian from 1490 and often traveling with him; his lament about having to wander like “ayn zigeyner” (like a gypsy) is famous (see » I. SL Life as an Emperor’s musician).[26] For this reason, portable keyboard instruments were necessary, but Hofhaimer also played on large church organs (» Orgel). On Maximilian’s behalf, he also supervised the construction of large organ works, such as in Innsbruck and Salzburg.[27] All these keyboard instruments had not only a practical musical function but also contributed to Maximilian’s reputation, as did the musicians who played them in his name. This is exemplified in the report of the envoys from Worms at the Imperial Diet in Cologne in 1505, describing Maximilian’s church attendance “mit sengern busunern pfyffern und orgeln und sunderdemselben mit aynem nüwen instrument der music uns gantz frembd kummen, auch demselben keynen nammen gebben” (with singers, trombonists, pipers, and organs, and also with a new musical instrument that was entirely unfamiliar to us and for which we had no name).[28] This is followed by a description of a regal with a greatly shortened resonator and reed pipes hidden inside the instrument’s body, making it seem to play without pipes. The sensation caused by such “new instruments” and the instrumental artists who played them is exemplified in the report on the festivities of the so-called Double Wedding in Vienna in 1515 (» D. Royal Entry):

“Hat der bischof von Wienn vnd kay. Ma. Capelln mit allerlay seitenspiln das hochambt gesungen / darunter vil newe vnd kunstliche saitenspil die man vor iar nit gehabt als das man Regal nennet vnd das ain Munch an alle pfeiffen erfunden / vnd aines das vogelgesang representiert / welche dan maister Paul organist der künstlichest in allen landen geschlagen hat.”[29]

(The Bishop of Vienna and the imperial chapel sang the High Mass with all kinds of instruments [saitenspil], including many new and artful instruments that had not been used before, such as the so-called regal without any organ pipes, invented by a monk, and another that imitated birdsong, which Master Paul, the most skilful organist in all lands, played.)A similar understanding can be applied to the famous woodcut by Hans Weiditz, which shows Emperor Maximilian attending Mass (» Abb. Kaiser Maximilians Kapelle). Here, opposite the imperial singers, Hofhaimer sits at a striking organ instrument, the so-called “Apfelregal.” The curious name comes from the appearance of the pipes, “dass es wie ein Apfell vffm Stiel stehet” (which stand like an apple on a stem), that is, above the short reed pipes (the “stem”) stands a round resonator (the “apple”).[30] The otherwise quite loud regals thus sound softer and quieter, and look striking.

“Musica süeß Meledey”: Instrumental Ensembles

Finally, in the Triumphzug, there is a fourth musicians carriage, “Musica süeß Meledey” (Music: sweet melody) (» Abb. Triumphzug Süße Melodie), whose “Maister” Maximilian had not yet determined. A total of eight musicians are depicted, with their instrumentation precisely specified:

„ain tämerlin, ain quintern, ain große laüten, ain Rÿbeben, ain Fydel, ain klain Raůschpfeiffen, ain harpfen, ain große Raůschpfeiffen.“ (a tämerlin, a quintern, a large lute, a Rÿbeben, a fiddle, a small rauschpfeife, a harp, a large rauschpfeife)[31]While these specifications were apparently clear to the illustrators, the exact identification of the instruments today is more difficult. The “tämerlin” is a one-handed flute and drum, a type of one-man dance music ensemble, as depicted several times in Freydal. “Quintern” and “large lute” refer to a duo of two differently sized lutes. Next are a viola da gamba, a fiddle or proto-violin, and a harp. The two rauschpfeifen are woodwind instruments with reeds enclosed in a wind cap, similar to the crumhorn. The named instruments did probably not play all together in this combination; rather, different individual ensembles are depicted here. The incompatibility is already evident in the different volume levels of the instruments, reflecting the late medieval distinction between “bas” (soft) and “haut” (loud). This also signifies a differentiation of performance venues, with (soft) string instruments being played in the chamber for a few listeners, versus (loud) wind instruments being played outdoors or in a large hall.

Instrumental Music at the Court of Maximilian I

While the personnel of Maximilian’s instrumental music can be relatively easily identified through archival records and documents, it is much more challenging to identify or even grasp the music played by these musicians. This is primarily because instrumental music at that time was rarely recorded and was essentially a non-written practice. In this sense, the musicians did not “improvise,” but rather they played “by heart,” so to speak, either based on oral tradition or as ad hoc creations.[32] Written records were mainly typical for vocal music – accordingly, in the Triumphzug, only the carriage of the “Musica Canterey” shows a music stand, while all other musicians perform without musical notation. Specific writings for instrumental music, known as tablatures, existed at the beginning of the sixteenth century for keyboard instruments and lutes. Indeed, music by Maximilian’s musicians is preserved in both notations: by Paul Hofhaimer and Adolf Blindhamer (Kap. Lute Intabulations by Adolf Blindhamer). Further sources of instrumental music can be identified from the title page of a songbook printed in four partbooks (Seventy-Five Beautiful Songs, Cologne: Arnt von Aich, 1514-1515): “In dissem buechlyn fynt man .Lxxv. hübscher lieder myt Discant. Alt. Bas. vnd Tenor. lustick zů syngen. Auch etlich zů fleiten / schwegelen / vnd anderen Musicalisch Instrumenten artlichen zů gebrauchen” (In this book one finds seventy-five beautiful songs with Discant, Altus, Bass and Tenor, pleasant to sing. Also some to play on flutes, shawms, and other musical instruments).[33] Accordingly, the songs, for which the lyrics are found separately in the tenor partbook, can also be performed instrumentally. Aich’s book is a reprint of at least two books printed by the Schöffer workshop, containing repertoire from Maximilian’s circle.[34] Therefore, the two Augsburg song prints “Aus sonderer künstlicher Art” (of special artistic kind) (» 1512) and “[68 Songs]” (» 1513), published by Erhart Oeglin, can also be claimed for Maximilian’s instrumental music, although it must be noted that this is clearly vocal music that could also be performed instrumentally.

This looks somewhat different in the case of a manuscript source for which a loose connection to the repertoire of Maximilian’s musicians is also suspected: the “Augsburger Liederbuch” (» D-As Cod. 2o 142a), a music manuscript created between 1505 and 1515, containing a mixed content of songs, chansons, and motets (including works by Josquin Desprez, Jacob Obrecht, Heinrich Isaac, Alexander Agricola, and Ludwig Senfl (» G. Kap. Senfls musikgeschichtliche Bedeutung) as well as some dance pieces.[35] These mostly untitled pieces can be identified as Italian dances, as brought back by musicians like Schubinger from their service in Italy. The statement by Maximilian, often cited in the literature in this context, in which he wrote from the Netherlands in 1479 that his pipers had “almost played him to death three or four times,” actually refers to whistling cannonballs fired at him by French gunners.[36]

Lute Intabulations by Adolf Blindhamer

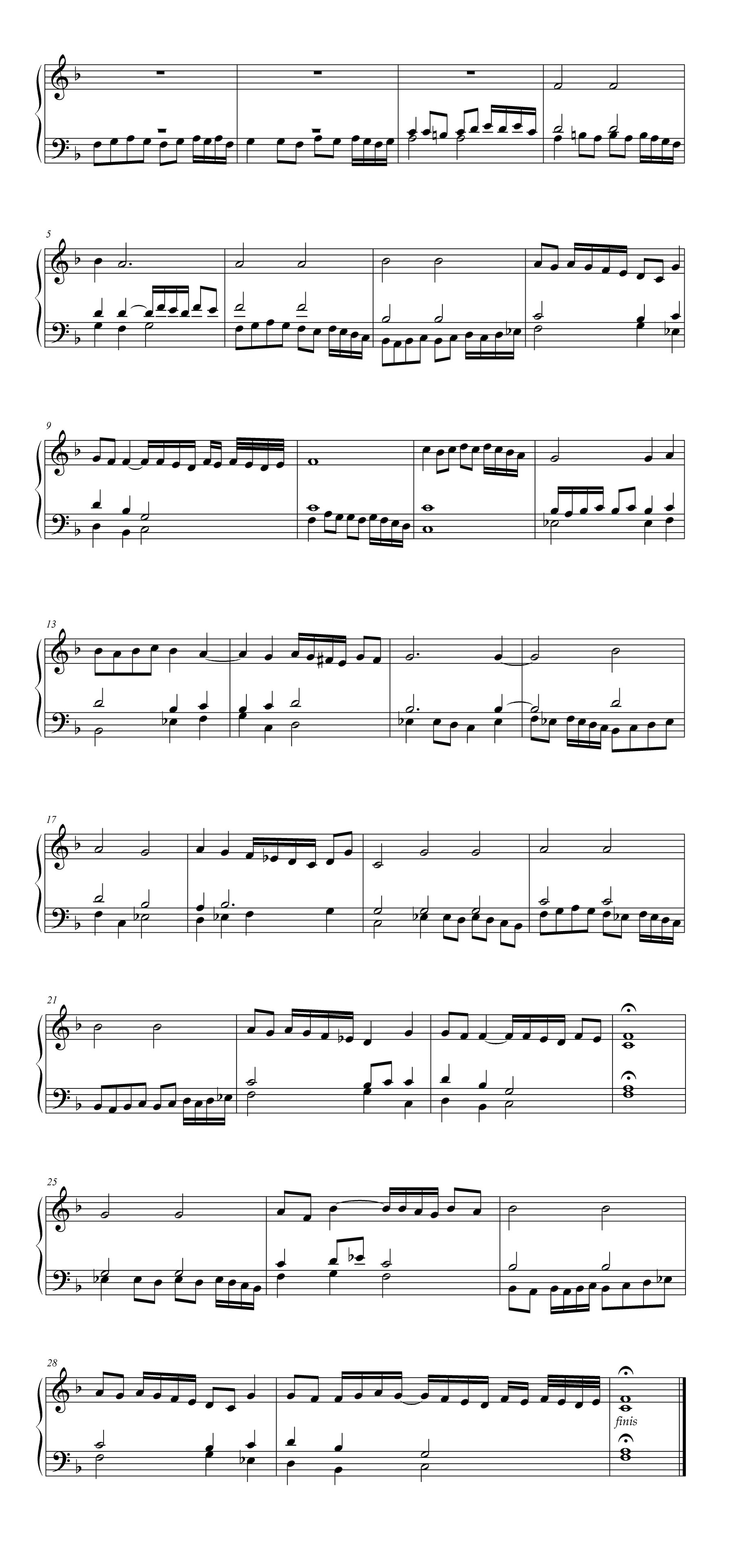

A slender manuscript with lute intabulations by Blindhamer (» A-Wn Mus. Hs. 41950), with an estimated date of around 1525, is not only one of the earliest surviving sources of lute music but also almost the only source from this period that records more complex music by a professional player rather than didactically simplified music for beginners.[37] It contains a long praeambulum (a fantasia-like free form), followed by instrumental pieces designated here as “Mutetae”, as well as intabulations of vocal compositions and some dance pieces. Besides Blindhamer himself, several composers are named: Josquin Desprez, Paul Hofhaimer (» C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik; » C. Paul Hofhaimer), Heinrich Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac), and Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl). Except for Josquin, these musicians were closely associated with Maximilian. This closeness perhaps also explains the existence of a unique piece, a “Muteta mester paulus hofhamer” (» Notenbsp. Muteta mester paulus hofhamer), which is only preserved in this manuscript.

The title carries the addition “mit 3 stymen” (with 3 voices) meaning that three voices were considered in the intabulation (other intabulations in the source even mention four voices, which indicates the special skill of both the intabulator and the player in preserving and playing, in the lute version, multiple contrapuntal voices). Musically, the virtuosic embellishments, called “coloration” at the time, stand out. Blindhamer’s presumed student Hans Gerle describes his playing as follows:

“Es hat auch gedachter Adolff (damit sein kunst vnd schickligkait erweittert werde) diese art gefürt / die dann alle Künstner der Musick vnd derselben Instrumenten haben sollen / wenn er bey verstendigen der Musica / oder vor berümbten Syngern geschlagen / hat er sich gleichwol zuuor in seinen Preambeln dermassen hören lassen / das sein geradigkait vnd kunst gewaltig erschinen ist / zusampt dem / so er zu einem gesatzten stücklein gegriffen / hat er das erstlich / wie es in noten gestanden / mit wenig Coloraturen / zum andern mit wolgestelten leuflein geziert / vnd zum dritten durch die Proportion geschlagen vnd volfürt / Vnd doch einer solchen gestalt / damit der süssigkait vnd vollkomenheyt des gesangs nichts benomen worden ist.”[38]

(Adolf (so that his art and skill may be extended) practiced this way, which all musicians and players of these instruments should follow. When he played before knowledgeable musicians or renowned singers, he first let himself be heard in his preludes, so that his precision and artistry appeared mightily. Additionally, when he played a written piece, he first played it with few embellishments, then adorned it with well-placed runs, and finally played it through proportional variations, without taking away the sweetness and completeness of the song.)After a prelude, which served both to tune the instrument and to attune the listeners and included virtuosic passages, Blindhamer played a written composition, such as the intabulation of a polyphonic vocal piece. The piece was played first with few embellishments, followed by a version with many runs and elaborations. Finally, the piece could be rhythmically varied in another repetition, without distorting the underlying composition. Remarkable is the repeated, always varied performance of usually short pieces mentioned here.

The piece by Hofhaimer, preserved only as a lute intabulation, highlights the significant gaps in the musical transmission that must be expected, as this is certainly not an original composition by Hofhaimer for the lute, but only an adaptation for this instrument. Such gaps are notable in the surviving music of Paul Hofhaimer. Although he was employed for life as an organist at the Habsburg court in Innsbruck in 1480, surprisingly little of his liturgical organ music has been preserved, even though this was the basis of his activity and fame. The elevation to knighthood in 1515, so important to him, took place in Vienna during the double wedding of Maximilian’s grandchildren. Following the ceremony, the imperial trumpeters played a fanfare, and the imperial chapel sang the Te Deum, and “in Organis Magister Paulus, qui in universa Germania parem non habet, respondit” (on the organ responded Master Paul, who has no equal in all of Germany).[39] This “responding” describes the so-called “alternatim practice,” in which the versets of a liturgical chant are alternately sung and played on the organ. The organist based his part on the liturgical tenor and demonstrated his skill by how artfully he adorned the cantus firmus. Only two of Hofhaimer’s organ settings have survived, perhaps recorded by his students—Hofhaimer himself probably extemporised them. His student Hans Buchner describes various methods of such chorale settings (even using the example of the Te Deum), but Hofhaimer’s practice also emerges from the two surviving organ pieces. Especially in the Recordare, based on the liturgical tenor, which was also appended to a Salve Regina like a hymn, the varied ways of handling the cantus firmus are evident, sounding in different voices and contrapuntal techniques in the three-voice setting.[40]

[1] For information on the Triumphzug, its different versions, and its complex history, see Appuhn 1979 and Michel/Sternath 2012; on its significance for Maximilian, see Müller 1982; on the relationship between depiction and reality, see Polk 1992; The quotation comes from the earliest surviving formulation of the iconographic program of the Triumphzug in 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (quotation from the Augsburg Baumeisterbücher of 1491, the council’s account books for income and expenses).

[5] See Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] See Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Quoted in Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] See Schwindt 2012.

[10] She received 50 guilders “zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung” (for her maintenance and living) in June 1520 when the court chapel was dissolved after Maximilian’s death; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Such as “Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher”, who were expressly paid for their services “bei Tanz” at the 1491 carnival; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] For a compilation of music-related illustrations, see Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] See Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[16] Polk 1992, 86 (with references from Augsburg archives).

[17] See Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] See Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (including the following).

[20] According to payments in the Augsburg (D-As) Baumeisterbuch 103 (1509), fol. 24v, and 104 (1510), fol. 28; kindly communicated by Keith Polk.

[21] See Jahn 1925, 10 ff., and Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] See Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] See the letter from Paul Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadian on May 14, 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So the wording in the formulation of the iconographic program in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] See Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, title page of the tenor partbook; for dating, see Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] See Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] See Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[36] Senn 1954, 26, referring to Maximilian’s letter in A-Wn, Cod. 10100b, fol. 15r–v, edited in Kraus 1875, 39. I owe the correction in this context to Grantley McDonald, who also drew my attention to the ‘Lauerpfeif’ (KHM Vienna, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, A 74), a cannon with two pipes attached to the side of the gun barrel that can be used to produce whistling sounds; see Krammer 2025.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; facsimile and description in Kirnbauer 2003. For lute tablatures of the next generation from the southern German-speaking area, see » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] See Moser 1966, 26 and 182, footnote 35.

[40] See Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; see also » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Recommended Citation:

Martin Kirnbauer: “Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).