The Secular Songs of the Monk of Salzburg

This article was written in the context of the ERC project ‘Music and Late Medieval European Court Cultures’ at the University of Oxford. This project has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 669190).

A Panopticum of Medieval Song

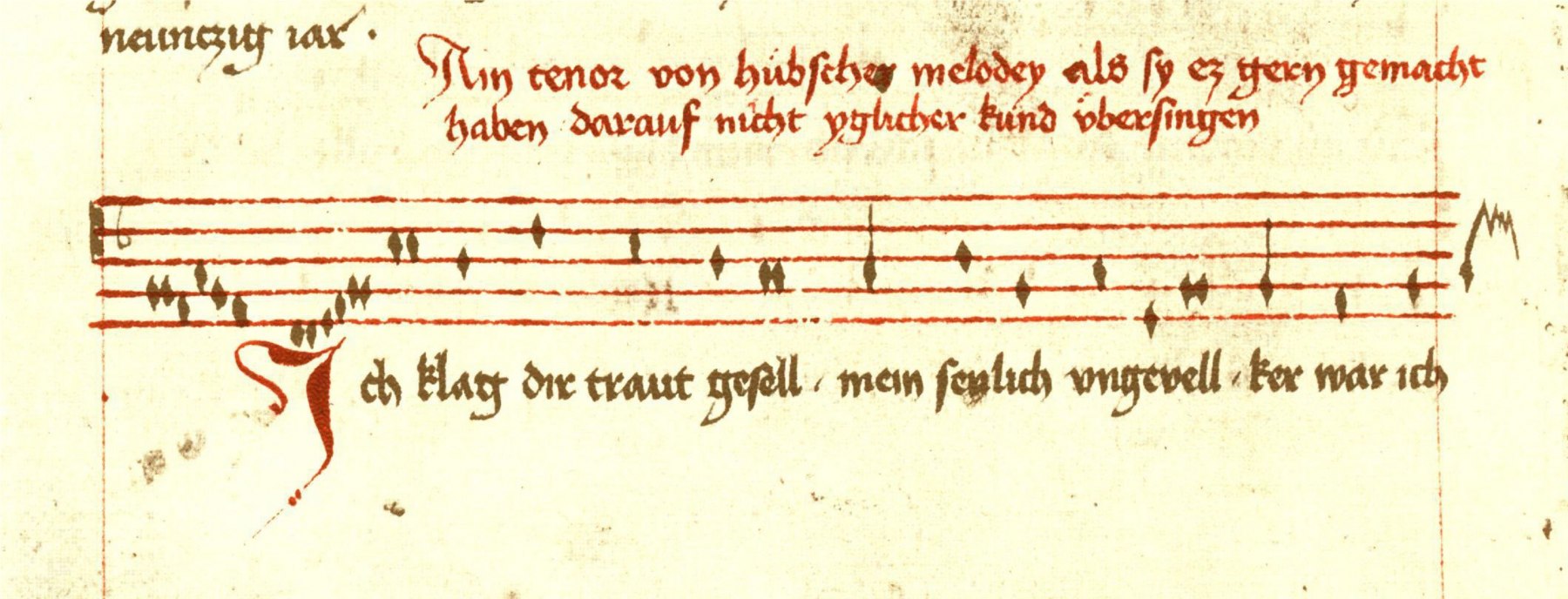

The fifty-seven secular songs attributed to the Monk of Salzburg constitute one of the most important corpora of vernacular German song in the later Middle Ages. [1] They form one half of an extensive œuvre, the remainder of which is made up of forty-nine religious songs, many of them translations of Latin sequences and hymns (on these see » B. Geistliche Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg).[2] The secular songs consist of seven polyphonic compositions—the earliest notated vernacular secular polyphony in the German-speaking lands—and fifty monophonic pieces. Sixteen of the monophonic pieces have a repeating form that bears some similarity to the ballade, but which are most likely not descended from contemporary French formes fixes.[3] (» Chap. The Monk’s Refrain Songs). Twenty-four of the monophonic pieces have a strophic form without Stollen, three of which are labelled in the Mondsee-Vienna manuscript as a “tenor” (» Fig. Ich klag dir, traut gesell).

Although the melodies for these pieces are through-composed, this is not necessarily true of the texts, which show a taste for elaborate rhyme-schemes, and often indeed use something resembling bar form. This disparity has led Reinhard Strohm to suggest that “tenor” in fact implies a melody that was transmitted without words and could be underlaid with words at will.[4] The remainder of the secular songs have idiosyncratic forms that evade classification. The Monk uses these forms to create songs that engage with various topics, including the life of the courtier, as well as the problems facing lovers, most prominently separation and the klaffer, the people who spread rumours at court. Some songs, such as the polyphonic Martinmas songs W54* Wolauf, lieben gesellen unverczait and W55* Martein, lieber herre and New Year songs such as W29 Ain gelügkleich iar nach deiner gier, are tied to particular seasons or festivals, but the majority are not occasional.

The Transmission of the Secular Songs of the Monk

The label “Monk of Salzburg” is probably a cipher for more than one member of the archiepiscopal court of Salzburg. Although composed under the auspices of Archbishop Pilgrim II of Salzburg, who ruled 1365-1396 (on Pilgrim, see » Ch. Salzburg under Archbishop Pilgrim II), the Monk’s secular songs are almost entirely transmitted in manuscripts from the first half and middle of the fifteenth century.[5] By far the most important source for the Monk’s secular songs is the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift, A-Wn Cod. 2856 (on which see » A. SL Die Notation der “Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift”).[6] Here almost 90 folios (three-quarters of the song collection that is sandwiched between legal texts and Konrad von Megenberg’s Buch der Natur) are devoted to fifty-three songs by the Monk, and only four of the secular songs are not recorded in it. In contrast to the extensive and scattered transmission of the religious songs, this most important witness to the secular songs was most likely produced alongside three other major witnesses in the Salzburg region in the mid-fifteenth century.[7] D, as the manuscript is known, is known to have been in the collection of the Salzburg goldsmith Peter Spörl in 1465, around a decade after its probable date of production. The scattered transmission of the Monk of Salzburg songs is considerable, and new concordances continue to appear, such as the one in » A-Wn Cod. 5455 (discussed by Marc Lewon: “A-Wn Cod 5455, fol. 180v – German “Tenors” from Vienna University” in: Musikleben–Supplement).

Ich klag dir traut gesell

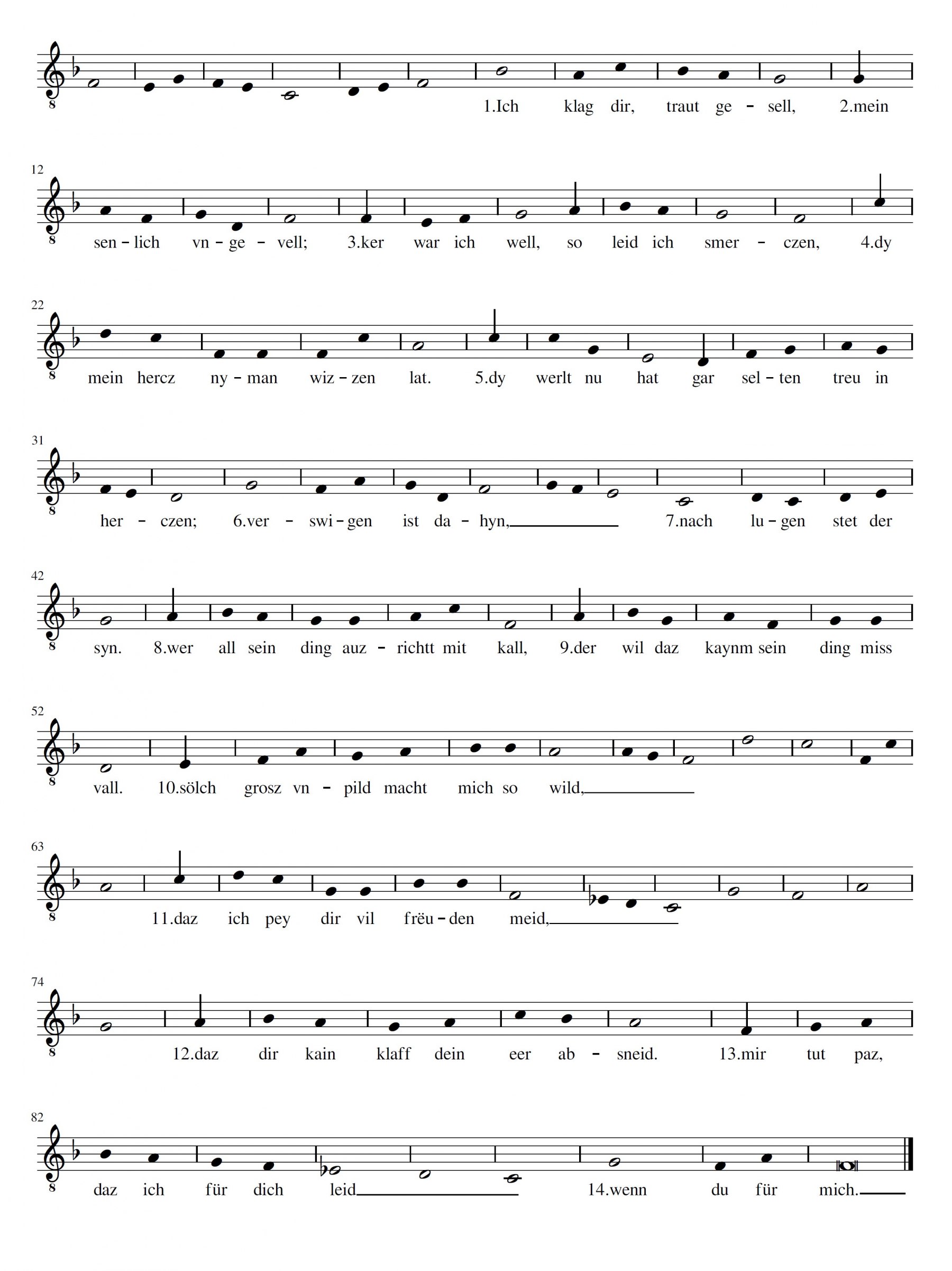

One of the tenores, Ich klag dir, traut gesell (W8), offers a typical instance of the concerns addressed in the Monk’s songs, and also exemplifies the masterful manipulation of metrics that makes the corpus such an important one. The tenor has the strophic form ●3a3a(3a)3’b 4c(2c)3’b 3d3d 4e4e(3f)3f ●4g ●4g4g3X. Here the symbol ● represents a melisma, bracketed rhymes are internal to the line, and X, following Germanist practice, represents the “Kornreim”, where a single rhyme sound returns in each strophe, bound to the same melodic phrase. Along with the intricacy of their rhyme patterns, the initial melisma and Korn are two of the principal hallmarks of the tenor form, one of the distinctive characteristics of the Monk’s songs (» Mus. ex. Ich klag dir, traut gesell).

Ich klag dir is also one of the handful of songs for which manuscript D offers hints on possible performance practice.

Ain tenor von hübscher melody,

Als sy ez gern gemacht haben,

Darauf nicht yglicher kund übersingen.(A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they used to like to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing discant to this.)

It appears, then, that this song was used as the basis for discantus.[8] In terms of its content, Ich klag dir, traut gesell is typical of the content of the love lyrics which make up a large proportion of the secular songs produced in Salzburg. In it, the singer addresses his beloved, discussing his fear of rumours that prevents him from achieving happiness with her, and bemoans the lack of honour in the world.

The Monk of Salzburg thereby typifies the Liebeslied discourse of the later Middle Ages, in which love affairs—as opposed to the forlorn longings of the Minnesänger for distant courtly ladies—have instead become more solid relationships, where separation of apparently mutually affectionate couples (rather than the lady’s refusal to unbend to the singer) is the source of greatest concern.[9] In this song, the lovers are separated by the fear of public discovery, and the male singer here longs for the day of their reunion (Str. 2, 13–14): “wy pald nymt end mein langez we,|wenn ich dich sich” (how soon my long woe will end when I see you), before he goes on to voice the concerns of the courtier about the reliability of those around him with secrets:

Bedenk, mein lobster hort,

Das pöse falsche wort

Groz lib zestort, und bis verswigen.

Dy lëut sint nu so wandelbër,

Sy sagent mër vnd lazzent nicht geligen (Str. 3, 1–5)(Remember, my darling treasure, that evil, false words can destroy the greatest man, and keep silence. People now are so changeable, they tell such stories and do not stop)

The song thus combines an exposition of the dangers of life at court in general, above all the possibility for rumours to circulate, even when—and perhaps particularly because—they are baseless, with a measure of laudatio temporis acti, or the praise of times past. It thus effectively examines the ramifications of the petty personality politics and the in-fighting of the courtly milieu, exploiting the possibilities of intricate and inventive rhyme schemes to imitate the echo-chamber of the court.

Salzburg under Archbishop Pilgrim II

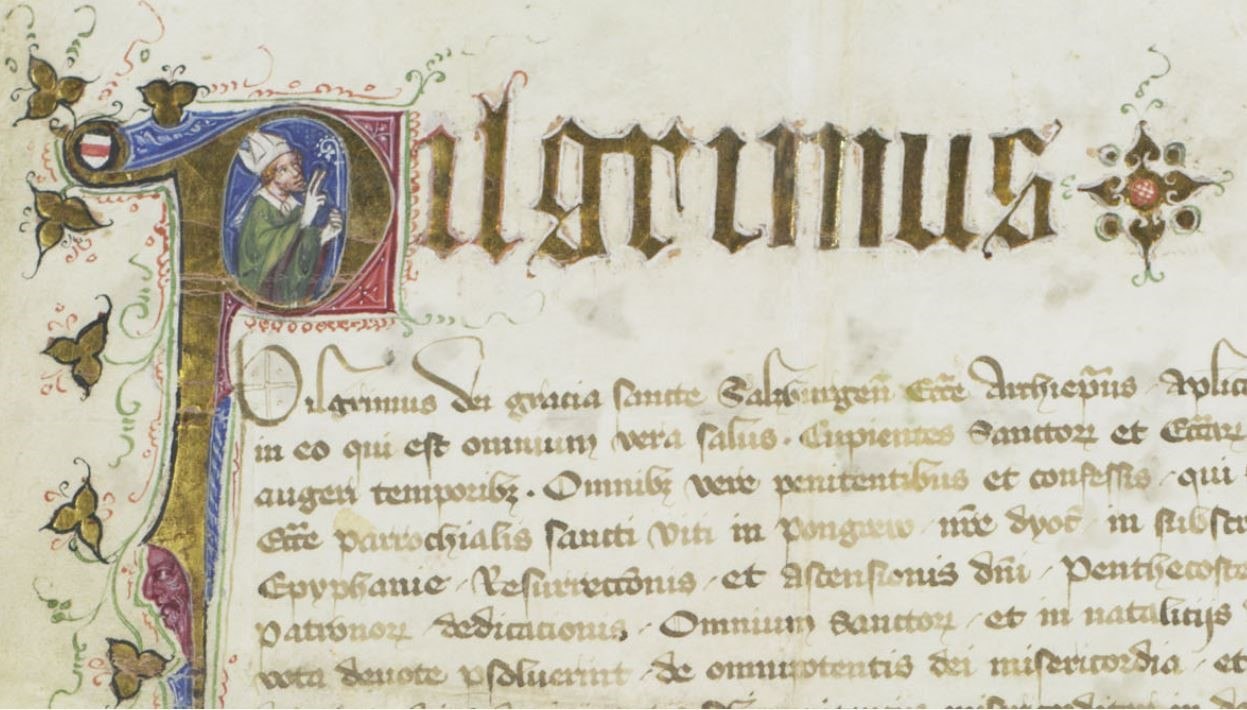

The specific historical court that is the implicit background to the Monk’s songs is that of Archbishop Pilgrim II von Puchheim, who ruled Salzburg as an independent ecclesiastical principality between 1365 and 1396. (See » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim)

The archbishop’s worldly authority extended over most of the current Bundesland Salzburg and included possessions in Styria and Carinthia, and in Carniola in modern Slovenia. Simultaneously, Salzburg’s ecclesiastical ambit (the two did not always overlap) extended over suffragans in modern Bavaria (Freising, Regensburg, Passau and Chiemsee), in Carinthia (Lavant, Gurk) and Styria (Seckau), as well as Brixen/Bressanone in modern Italy. Enjoying close connections with the King of the Romans Wenceslas in Prague, as well as long-standing familial ties to the Habsburg dukes of Austria, Archbishop Pilgrim and his court were well-placed to benefit from the cultural capital of the time.[10]

Pilgrim’s reign was a combination of great political exploits on a regional, indeed continental, scale, improved fiscal security and management of the Hochstift’s resources (notably the essentially important salt-works, but also shipping along the Salzach). It is no surprise that his portrait was painted even in charters concerning his ordinary ecclesiastical administration: see » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim.

Thus when Pilgrim’s tombstone described him as being ‘potens in opere et sermone’ [‘powerful in deed and word’], this is not merely empty rhetoric.[11] The thirty years of his reign were a period of great expansion of the Hochstift Salzburg, and saw it reach its greatest territorial extent with the acquisition of the provostship of Berchtesgaden in 1393.[12]

While the horizons of the Hochstift at large expanded, the court itself became more introverted, as more positions of authority in Salzburg were handed off to Pilgrim’s close relatives. Multiple brothers and brothers-in-law became Hauptmann of Salzburg (the master of the Hohensalzburg fortress high above the city and officer responsible for law and order).[13] Similarly, the suffragan bishoprics of Chiemsee and Seckau went to Pilgrim’s nephews, Georg and Johann von Neidperg respectively.[14] This flourishing nepotism was accompanied by an apparent reduction in the size of the archbishop’s privy council (although it has been suggested that this is the contrast between a larger ‘plenary’ council and a smaller daily circle[15]). Pilgrim’s reign also sees the appearance of new office-holders in the council, which until the beginning of the fourteenth century had been largely clerical: now these were mainly laymen, Vizedom (1360), Oberster Schreiber and Hauptmann (1370), Domdechant as official and the chancellor (1377), and Hofmarschall (1382).[16] This change in the composition of the court no doubt had its effect on the artistic production in Salzburg.

The Court in the Songs of the Monk

The historical court of the Archbishop of Salzburg has its literary-musical echo in a number of the Monk’s songs. One of the most interesting of these is W19, Wier, wier der fünfzehent an der schar, which, on behalf of all the members of the court, addresses all the women who have injured them. Imitating exactly the form of a charter, from the introductory formula to the place and date at its end, Wier, wier is typical of the ingenious and playful approach to song-writing in Salzburg. Proposed by Franz Viktor Spechtler to have been composed at the Reichstag in Nuremberg in 1387, it is above all interested in the responsibilities of the good member of the courtly society,

Gesellschaft ist also gericht,

Das kain artikel sey nicht pricht.

Ein schalkch verirret gar die slicht;

Wie wol sölich dingk durch guet geschicht,

der volg yem unnser keiner gicht;

Den süll wir hassen vestiklich,

Wenen wir sein purgersinn unstët (Str. 2, 5–11)(Courtly society is so inclined that it breaks no article of faith. A trouble-maker confuses the flow of things. However easily such a thing could happen for the best of reasons, no one among us will follow such a canker. We should instead hate him with passion, if we think his civic sense is insecure.)

Those, the song goes on, who are inconstant will not be allowed into the council. The courtly society is one that depends on trust. Where elsewhere (as in Ich klag dir, traut gesell) the songs play through notions of loyalty under the guise of the amatory relationship, in Wier, wier, the importance of trust to one’s social standing is discussed more or less openly here. While the amatory metaphor (one that reaches back to the earliest days of Minnesang in the twelfth century; see » B. Minnesang und alte Meister) is evoked at the beginning of W19, this song is all about standards in public life and conformity to conventions, something underscored in playful fashion by its already mentioned imitation of a charter.

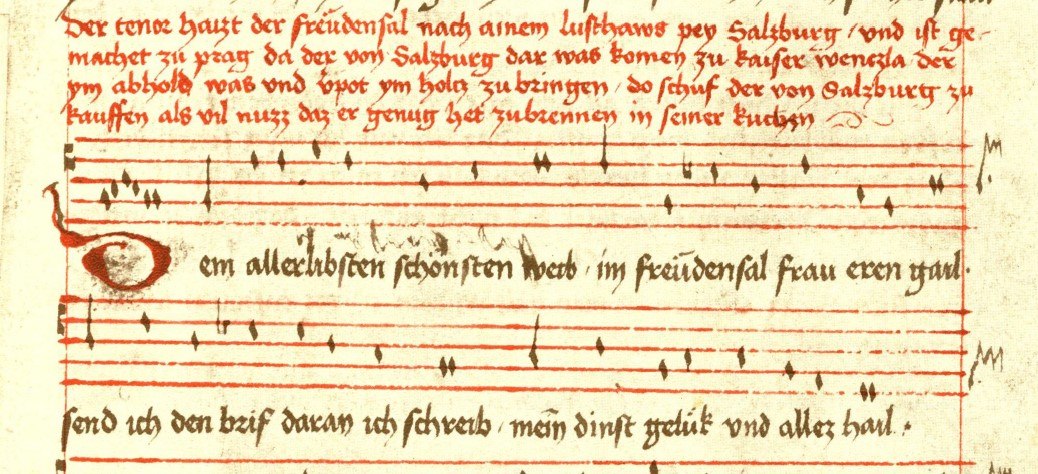

One of the most commented pieces in the Monk’s secular corpus, Der frëudensal: Dem allerlibsten schönsten weib (W7), which takes the form of a letter to “frau Erengail” (Lady Greedy-for-Honour) is dated to carnival (Fastnacht) 1392. The supposed writer describes himself in the piece as “pilgreim”, a play on the name of the Archbishop that fed the idea, now generally abandoned, that Pilgrim von Puchheim was himself the Monk.[17] This connection to the prelate is made all the more concrete by the rubric appended to the poem in MS D (A-Wn Cod. 2856), f.190r. It describes the occasion for the apparent composition of the song Dem allerlibsten schönsten weib, the tenor of which it calls “Der Freudensaal”, during a visit by Pilgrim von Puchheim to the King of the Romans Wenceslaus IV in Prague. (See » Fig. Der tenor haizt der freudensaal: Monk of Salzburg)

Der tenor haizt der Frëudensal nach ainem lusthaws pey Salzburg, und ist gemacht zu Prag, da der von Salzburg da was komen zu kaiser Wenczla, der ym abhold was und verpot ym holz zu bringen. do schuf der von Salzburg zu kauffen als vil nuzz, daz er genug het zu brennen in seiner kuchen. (D, f. 190r)

(This tenor is called ‘The House of Joy’, after a pleasure house near Salzburg, and was made in Prague, when the Salzburger (sc. Archbishop Pilgrim) had gone there to see Emperor Wenceslas, who was unkind to him and forbade anyone to bring him wood. So the Salzburger required so many nuts to be bought that he would have enough to burn in his kitchen.)

The most extensive of any of the rubrics in the manuscript, it alleges that the song was composed in Prague, although Pilgrim is not recorded as having visited the city that year. Whether accurate or not, the rubric responds to the reality effects written into the song text and offers the fifteenth-century user a substitute connection with the fourteenth-century events described.

The Monk’s Refrain Songs

One of the peculiarities of the Salzburg corpus is the group of sixteen songs using a form that combines elements of the virelai and ballade. These were a mainstay of French vernacular song culture from the mid-thirteenth century and found their classical expression in the work of Guillaume de Machaut.[18] The cluster of songs in Salzburg exhibiting this form type has normally been interpreted as evidence of the closeness of cultural as well as diplomatic ties between the Hochstift and the French-speaking world (for another instance of these connections, see » Ch. Networking the Monk of Salzburg: Ju, ich jag). It has also been suggested, though this seems highly unlikely, that inspiration came more or less directly from Machaut himself by way of Prague, where he was secretary to King John of Luxemburg for more than a decade, and where Archbishop Pilgrim visited John’s grandson Wenceslas IV, King of the Romans, on a number of occasions (» Ch. The Court in the Songs of the Monk).[19] The refrain songs produced in Salzburg share with the French type, exemplified by Machaut, the general AABB form, but depart in the greater length of their refrain, which always follows the strophe (whereas Machaut’s sometimes precede it), and the prevalence of a brief initial melisma to both A sections. As such it is most probable that the Salzburg refrain songs drew their inspiration from earlier German traditions or perhaps from Romance trends from before the crystallization of the classical formes fixes.

For example, the May song W50, Seint röslein, plüemlein maniger lay has the form:

A

A

B

B (Refrain)

●4aaa6b

●4ccc6b

4dedd(d)ffe

4ghgg(g)iih

The singer focusses on how he can win “von prawnen wolgemuet|ain krënzlein […] von meiner liebsten frawen” and dance with her in the circle. The association of the chaplet with female virginity, a standard topos since the earliest courtly love-lyric, is heightened by the fact that this one is made of marjoram, which flowers in the autumn and was valued as an aphrodisiac.[20] Beyond this, the colour brown was traditionally associated with the female genitalia. The second strophe leaves the allusive in favour of the obscene, talking about flowers that lie above the “Happy Valley” (“frëwdental”, Str. 2, 1). Evidently, the fact that these songs were produced in the shadows of a Prince of the Church had little impact on their contents. It is perhaps a little more surprising that the same material could be found in a monastic context: the first strophe of this song was copied into » D-Mbs Clm 14256 (f.105r) at the Abbey of St Emmeram in Regensburg alongside the Monk’s translation of the Easter sequence Mundi renovatio.[21]

Who sang for whom in Salzburg?

The question of exactly who composed the songs often only labelled as münchs in many of the manuscript sources has elicited many different answers (on this question see further Stefan Engels » Kap. Widersprüchliche Forschungsmeinungen zum Mönch and » Kap. Schriftliche Zeugnisse über den Mönch). As noted (» Kap. A Panopticum of Song) it is highly unlikely that all 106 songs attributed to the Monk were indeed composed by a single individual. Christoph März, in his edition of the secular songs, attempted to attribute each of the secular songs to one of three ‘layers’(Schichten). Layer II, that furthest from the core—and thus furthest from the individual “Monk”—is particularly rich in refrain forms. This invites the suggestion that the refrain songs offered a flexible basis for less gifted poets among the courtiers at Salzburg to join in the common interest in vernacular song. For example, the songs W48, W49 and W53 (all in März’s Layer II, and all unique to the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift, A-Wn Cod. 2856) are marked by a certain derivative quality. W48, ‘Ich het czu hannt gelocket mir’, as Ingrid Bennewitz-Behr proposed, imitates a song by Heinrich von Mügeln.[22] The fact that it might be doing this in the female voice makes it unique in the Monk corpus, where female voices only appear in the context of dialogue songs such as the polyphonic pieces W3, 4 and 5, and the tenor-type song W57* (W4: » Hörbsp. ♫ Untarnslaf – Das kchúhorn).

The presence of female voices supports the idea that the Monk songs were responding to a highly varied audience.[23] Salzburg was thus, it seems, a court where participation in the making and appreciation of song was constitutive to the establishment and delineation of a courtly community. We can perhaps also draw comparisons with narrative sources from the time.[24]

Networking the Monk of Salzburg: Ju, ich jag

As has already been noted, the Monk’s secular songs record the extensive cultural networks that fed Salzburg in the fourteenth century. Most prominent among these is the Monk’s three-part canon Ju, ich jag, which is a contrafactum of the Old French chace Umblemens vos pri merchi.[25]

By and large, the Monk does not seem to engage with the French text. The label “chace” implies a hunting scene, but beyond the nod in the Monk’s incipit (“I hunt with my heart by day and night”), Ju, ich jag is not about hunting nor even, really, a chase of any kind.[26] Rather it is for the most part a highly detailed description of the perfect courtly lady, as a kind of projection screen for male desire and medieval discourses on beauty. Following the ancient topos whereby external beauty reflected inner virtue, the singer declares that his lady is perfect in every respect:

Sust all tail hant gelück und hail,

Ynnikleichen, mynniklichen,

Schön polieret, durch visieret.

Des mues ymmer haben dangk

Die lieb natur,

Dy pildet sülch figure. (E2, 41–46)(And so all parts have joy and salvation,

Inwardly, lovingly,

Finely polished, thoroughly sculpted

For that we must forever thank lovely Nature,

Who shapes such figures.)“Polieret” and “durch visieret”, seem to indicate that the Monk was indeed, in some measure, acquainted with French, and that therefore—presuming that he was in possession of both text and melody of Umblemens—it was indeed a choice available to him to engage with the French song or not. It is witnessed only once in its entirety and with music in the Ivrea manuscript (I-IV 115), but is also mentioned in the Trémoïlle manuscript (» F-Pn nouv. acq. fr. 23190).[27] The first of these witnesses was probably compiled around 1385 by Savoyard clerics at Ivrea in northern Italy; the manuscript testifies to strong ties to the Valois court in Paris, and by extension to the Papal court at Avignon.[28] The second witness is in the index to the now lost Trémoïlle manuscript, which seems to have been copied by one of Charles V’s chaplains, Michel de Fontaine, most likely for Jean II or the duke of Burgundy.[29] Ju, ich jag in this way bears witness to the adoption in Salzburg of musical art produced for the very highest ranks of fourteenth-century French society.

The Reception of the Monk’s Secular Songs

The earliest traces of the Monk’s songs point to a perhaps unsurprising popularity among monastic and clerical milieux, for example at St Emmeram’s abbey in Regensburg[30] (see » Ch. The Monk’s Refrain Songs), and at Göttweig, where a Latin version of the Martinmas canon W55*, Ain radel: Martein, lieber herre, was composed.[31] (This last can be heard here: » Audio ♫ Martein, lieber herre.) This parallels the early appearance of religious songs by the Monk in the Engelberg manuscript (» CH-EN, Cod. 314), where the future abbot Walther Mirer appears to have copied three of the Monk’s translations, G6, G40, and G47 before 1380, most probably not long after their composition.[32] Further important evidence of the circles in which the Monk’s music first achieved popularity is the witness to the Monk’s ‘Taghorn’ and a number of refrain songs among similar compositions by other poets in the Sterzing miscellany (» I-VIP o. Sign.). This manuscript from the first decade of the fifteenth century, perhaps compiled among the cathedral canons of Brixen or at the Augustinian house at Neustift/Novacella,[33] bears witness to the tastes of a noble, secular-clerical milieu, similar to that which had originally given rise to the songs in Salzburg.[34]

Later in the fifteenth century, a number of cases bring the Monk into contact with Oswald von Wolkenstein, active around half a century after the Monk (see » B. Oswalds Lieder). While these are above all cases of the Monk and Oswald being transmitted together (for instance Oswald’s Mittit ad virginem alongside the Monk’s translation in MS A, » D-Mbs Cgm 715), there are two instances in which it seems that Oswald did indeed know songs by the Monk. First, the Monk’s W15, Ain liblich weib, der zarter leib, a song with a curious form that combines elements of the tenores and the refrain songs, is imitated by Oswald in his Kl 78, Mich tröst ein adeliche mait (März 1999, 404–406), which systematically re-uses the same rhyme sounds. It has also been suggested, although it is hard to prove conclusively, that Oswald knew Iu ich jag (W31, » Ch. Networking the Monk of Salzburg: Ju ich jag), and quoted in his song Kain ellend tet mir nie so and (Kl. 30).[35]

Any direct knowledge may have come via the Augustinian foundation at Neustift or the cathedral convent at Brixen (a suffragan see of Salzburg), with which Oswald had long-standing connections, not least that his son Michael became a cathedral canon in Brixen in 1440.[36]