Ich klag dir traut gesell

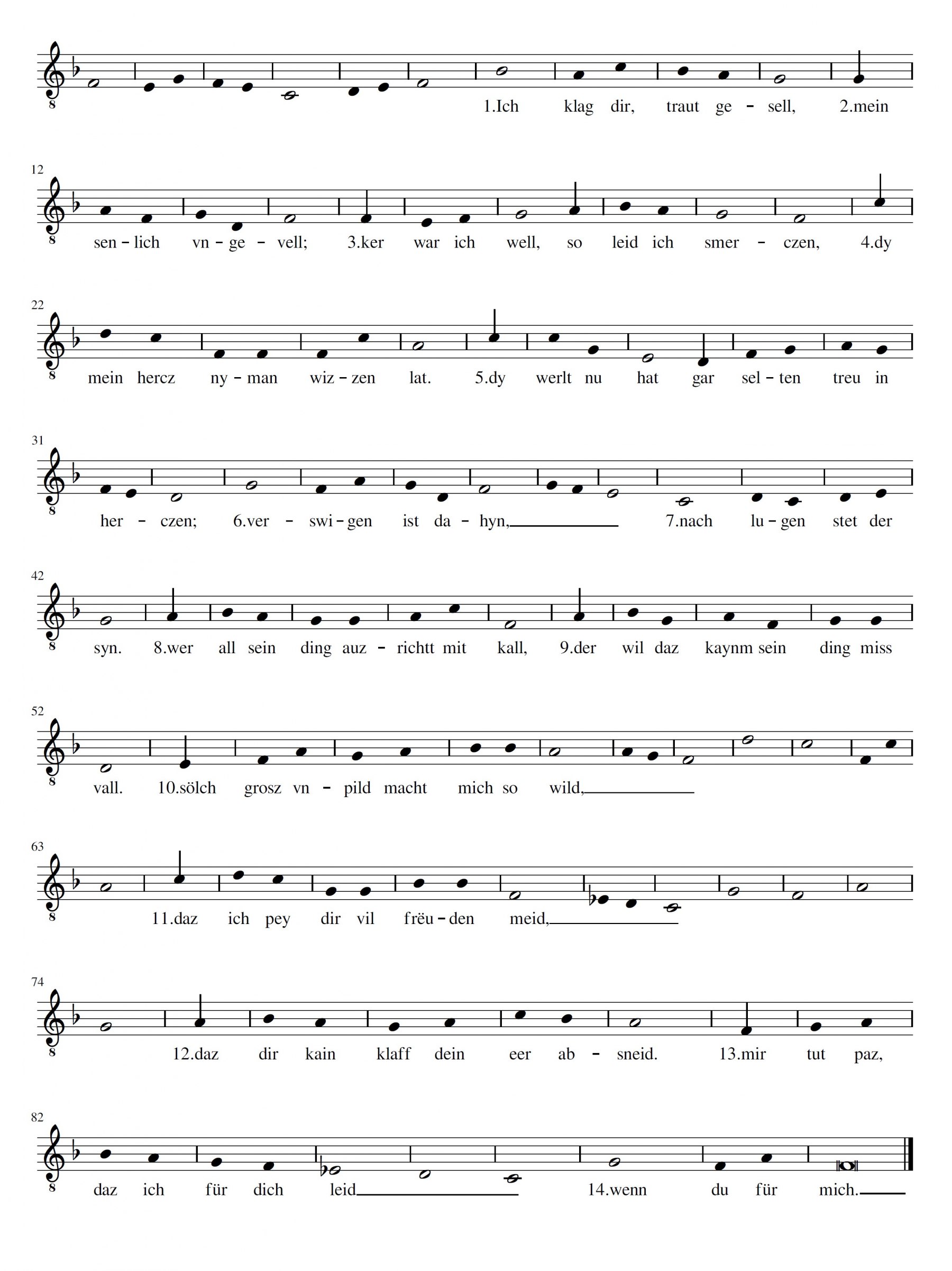

One of the tenores, Ich klag dir, traut gesell (W8), offers a typical instance of the concerns addressed in the Monk’s songs, and also exemplifies the masterful manipulation of metrics that makes the corpus such an important one. The tenor has the strophic form ●3a3a(3a)3’b 4c(2c)3’b 3d3d 4e4e(3f)3f ●4g ●4g4g3X. Here the symbol ● represents a melisma, bracketed rhymes are internal to the line, and X, following Germanist practice, represents the “Kornreim”, where a single rhyme sound returns in each strophe, bound to the same melodic phrase. Along with the intricacy of their rhyme patterns, the initial melisma and Korn are two of the principal hallmarks of the tenor form, one of the distinctive characteristics of the Monk’s songs (» Mus. ex. Ich klag dir, traut gesell).

Ich klag dir is also one of the handful of songs for which manuscript D offers hints on possible performance practice.

Ain tenor von hübscher melody,

Als sy ez gern gemacht haben,

Darauf nicht yglicher kund übersingen.

(A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they used to like to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing discant to this.)

It appears, then, that this song was used as the basis for discantus.[8] In terms of its content, Ich klag dir, traut gesell is typical of the content of the love lyrics which make up a large proportion of the secular songs produced in Salzburg. In it, the singer addresses his beloved, discussing his fear of rumours that prevents him from achieving happiness with her, and bemoans the lack of honour in the world.

The Monk of Salzburg thereby typifies the Liebeslied discourse of the later Middle Ages, in which love affairs—as opposed to the forlorn longings of the Minnesänger for distant courtly ladies—have instead become more solid relationships, where separation of apparently mutually affectionate couples (rather than the lady’s refusal to unbend to the singer) is the source of greatest concern.[9] In this song, the lovers are separated by the fear of public discovery, and the male singer here longs for the day of their reunion (Str. 2, 13–14): “wy pald nymt end mein langez we,|wenn ich dich sich” (how soon my long woe will end when I see you), before he goes on to voice the concerns of the courtier about the reliability of those around him with secrets:

Bedenk, mein lobster hort,

Das pöse falsche wort

Groz lib zestort, und bis verswigen.

Dy lëut sint nu so wandelbër,

Sy sagent mër vnd lazzent nicht geligen (Str. 3, 1–5)

(Remember, my darling treasure, that evil, false words can destroy the greatest man, and keep silence. People now are so changeable, they tell such stories and do not stop)

The song thus combines an exposition of the dangers of life at court in general, above all the possibility for rumours to circulate, even when—and perhaps particularly because—they are baseless, with a measure of laudatio temporis acti, or the praise of times past. It thus effectively examines the ramifications of the petty personality politics and the in-fighting of the courtly milieu, exploiting the possibilities of intricate and inventive rhyme schemes to imitate the echo-chamber of the court.

[8] On an instance where the Monk’s songs were adopted in a less informal polyphonic context, see Welker 1984/1985, on the use of the Monk’s Taghorn (W2) as a tenor for a two-part setting of the ‘Veni rerum conditor’ in the St Emmeram codex, » D-Mbs Clm 14274.

[9] On the shift in the discourse on love in German lyric during the earlier fourteenth century, see Janota 2007.