Salzburg unter Erzbischof Pilgrim II.

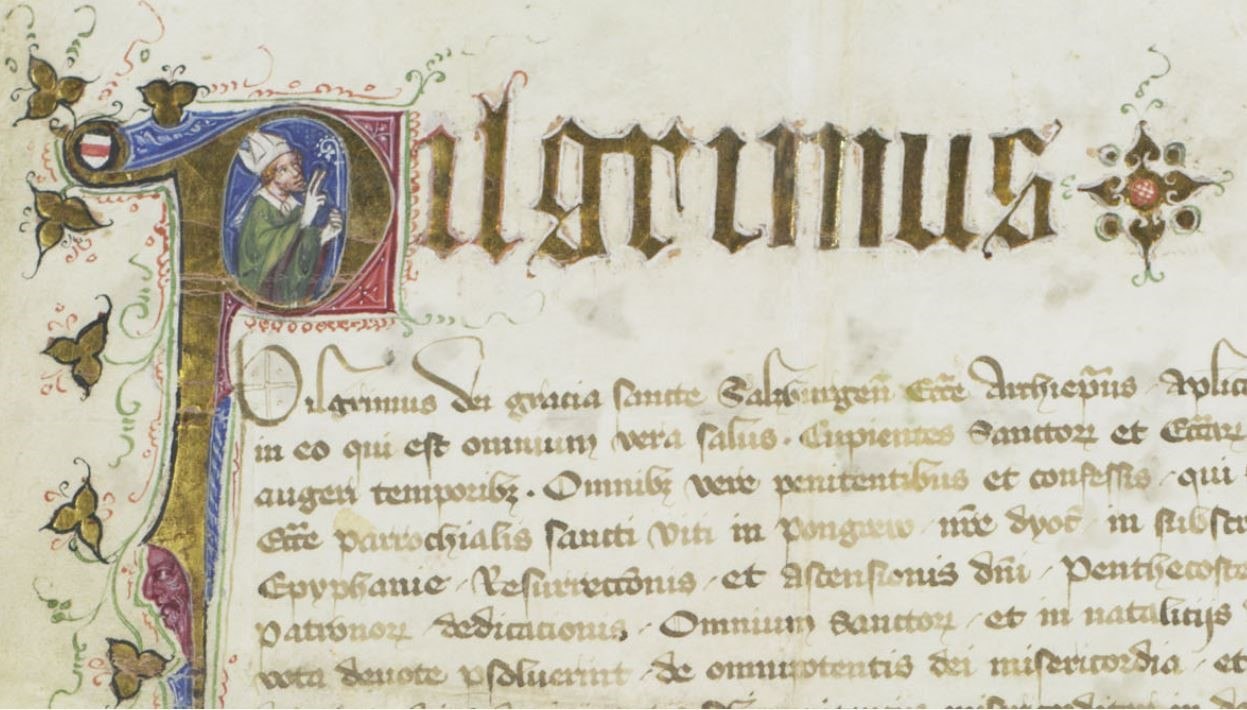

The specific historical court that is the implicit background to the Monk’s songs is that of Archbishop Pilgrim II von Puchheim, who ruled Salzburg as an independent ecclesiastical principality between 1365 and 1396. (See » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim)

The archbishop’s worldly authority extended over most of the current Bundesland Salzburg and included possessions in Styria and Carinthia, and in Carniola in modern Slovenia. Simultaneously, Salzburg’s ecclesiastical ambit (the two did not always overlap) extended over suffragans in modern Bavaria (Freising, Regensburg, Passau and Chiemsee), in Carinthia (Lavant, Gurk) and Styria (Seckau), as well as Brixen/Bressanone in modern Italy. Enjoying close connections with the King of the Romans Wenceslas in Prague, as well as long-standing familial ties to the Habsburg dukes of Austria, Archbishop Pilgrim and his court were well-placed to benefit from the cultural capital of the time.[10]

Pilgrim’s reign was a combination of great political exploits on a regional, indeed continental, scale, improved fiscal security and management of the Hochstift’s resources (notably the essentially important salt-works, but also shipping along the Salzach). It is no surprise that his portrait was painted even in charters concerning his ordinary ecclesiastical administration: see » Fig. Throne Seal Pilgrim’s II. of Puchheim.

Thus when Pilgrim’s tombstone described him as being ‘potens in opere et sermone’ [‘powerful in deed and word’], this is not merely empty rhetoric.[11] The thirty years of his reign were a period of great expansion of the Hochstift Salzburg, and saw it reach its greatest territorial extent with the acquisition of the provostship of Berchtesgaden in 1393.[12]

While the horizons of the Hochstift at large expanded, the court itself became more introverted, as more positions of authority in Salzburg were handed off to Pilgrim’s close relatives. Multiple brothers and brothers-in-law became Hauptmann of Salzburg (the master of the Hohensalzburg fortress high above the city and officer responsible for law and order).[13] Similarly, the suffragan bishoprics of Chiemsee and Seckau went to Pilgrim’s nephews, Georg and Johann von Neidperg respectively.[14] This flourishing nepotism was accompanied by an apparent reduction in the size of the archbishop’s privy council (although it has been suggested that this is the contrast between a larger ‘plenary’ council and a smaller daily circle[15]). Pilgrim’s reign also sees the appearance of new office-holders in the council, which until the beginning of the fourteenth century had been largely clerical: now these were mainly laymen, Vizedom (1360), Oberster Schreiber and Hauptmann (1370), Domdechant as official and the chancellor (1377), and Hofmarschall (1382).[16] This change in the composition of the court no doubt had its effect on the artistic production in Salzburg.

[10] On the Puchheim dynasty, which flourished into the eighteenth century, see Tepperberg 1978.

[11] Pagitz 1968, 140. On the chapel Pilgrim founded, see » B. Geistliche Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg, Kap. Pilgrim II. von Puchheim, and also Hauthaler u. a. 1891, 389–390.

[12] The best account of Archbishop Pilgrim’s life is still Klein 1937/1938.

[13] On the office of Hauptmann, see Spechtler 1963, 176–177.

[14] On Georg, see Klein u. a. 1952, 42.