“Multiple Meanings”: Jacob Obrecht’s Missa Salve Diva Parens and the Coronation of Maximilian

Occasions for the Creation of (Late) Medieval Compositions

For compositions from the (late) Middle Ages, it is rarely possible to determine exact dates or even occasions of origin. Such localizations are most feasible in the realm of the so-called “state motet,”[1], where specifically commissioned Latin texts mention concrete names or events (» D. Isaac und Maximilians Zeremonien, » I. Isaac’s Amazonas, » D. Albrecht II. und Friedrich III.). However, it is exceedingly rare that we can determine specific occasions for the composition of settings of the Mass Ordinary (“Mass settings”). Because they set the fixed liturgical text, such settings are generally suitable for any polyphonically structured Mass celebration.

Nevertheless, there are ways to narrow down the time of origin of a composition—through codicological analysis, for example—and to infer, based on the use of specific textual and musical material, on which days a Mass may have been particularly appropriate. The use of a liturgical melody (e.g., for Easter, Christmas, Marian feasts, specific saints) as a cantus firmus can indicate the liturgical context for which the setting was created. Sometimes, such analysis even allows us to establish a connection to precisely dated Mass foundations.[2]

The following study aims to propose a contextualization for Jacob Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens and present the underlying circumstantial evidence—while fully acknowledging that this can only ever be a well-founded hypothesis rather than definitive proof. Moreover, this example demonstrates how such (hypothetical) localizations can open up perspectives for new interpretative possibilities.

Jacob Obrecht's Missa Salve diva parens and Archduke Maximilian

Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens is the opening piece of the choirbook » A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495, which was produced for Maximilian I around 1508-1510 in connection with his journey to the Netherlandsfollowing his proclamation as Emperor Elect and the conclusion of the “League of Cambrai” (December 10, 1508). The repertoire for this splendid manuscript was generally selected based on its relation to Maximilian himself or his daughter Margaret (see » D. Musikalische Huldigungsgeschenke, Kap. Zum Repertoire der Handschrift A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495). Within the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript complex, the first composition in a codex is typically the one most closely associated with the dedicatee. The opening page is usually also the most richly illuminated, often adorned with the coats of arms of the recipients of the gift—as is the case here, with those of Emperor Maximilian I and his (second) wife, Bianca Maria Sforza (» Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens). Notably, Missa Salve diva parens was already quite old (approximately 25 years) at the time of its inclusion, in contrast to the following repertoire, and underwent a modernizing revision during the copying process (see » C. Medien mehrstimmiger Vokalmusik).

This finding suggests that the Mass was probably associated with a significant event in Maximilian’s life: otherwise, there would be little reason to place such a comparatively “old” work at the forefront of a manuscript explicitly compiled for Maximilian, and to modernize it specifically for this purpose.

Missa Salve diva parens was copied in manuscript at Rome as early as late 1487 or early 1488 in the choirbook » V-VCbav (ehemals I-Rvat) Capp. Sist. 51[3] – and was possibly brought there by Obrecht himself in early 1488.[4] This dating places the composition in a period about which we know extraordinarily little regarding Maximilian’s court music. In 1482, his wife Mary of Burgundy had died in a riding accident, leaving Maximilian (as guardian of their four-year-old son Philip) in charge of Burgundian affairs. The highly renowned Burgundian court chapel, which Mary had inherited from her father in 1477 and which comprised more than twenty singers, seems to have been neglected by Maximilian due to ongoing warfare. Consequently, very little is known about the court’s musical repertoire in the 1480s.[5] A notable testament to Mary’s and Maximilian’s (Marian) piety—expressed in a daily polyphonic Marian Mass—is the richly endowed Mass foundation that Mary of Burgundy arranged on her deathbed for the Church of Our Lady Bruges’, which Maximilian brought into being.[6] However, the repertoire performed there remains unknown.

In the autumn of 1485, Maximilian undertook a large-scale reorganization of the Burgundian court chapel. In anticipation of his reunion with his father, Emperor Frederick III, and in preparation for his hoped-for coronation as king, he recruited the finest and most experienced singers from across Europe and dressed them lavishly in signal red, as described by the Burgundian court chronicler Jean Molinet (1435–1507)[7] The chapel played a key role in the months-long festivities surrounding the royal election and coronation and accompanied Maximilian on his subsequent journey through Artois, Flanders, and Brabant. Thereafter, sources fall silent again—political turmoil, including the Burgundian succession war and ongoing conflicts with France, once more created difficult circumstances. The next documented reference comes only in late 1488 when, after his captivity in Bruges (January–May 1488), Maximilian left the Netherlands and compensated several court chapel members with significant payments (» I. Maximilian’s Court Chapel). By the early 1490s, his son, Archduke Philip, had officially taken over the Burgundian chapel.[8]

The association between Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens and Archduke (later King) Maximilian, suggested by its prominent position in the prestigious choirbook A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495, is particularly noteworthy given the loss of sources concerning the Burgundian-Habsburg court chapel in the 1480s. This composition provides at least one tangible piece of evidence linking Obrecht’s work to the chapel’s repertoire in the later 1480s. Additionally, until now, research had not assumed any connection between Maximilian and Obrecht (c. 1457/58–1505), who began composing Mass settings around 1480 (see » G. Jacob Obrecht).

In addition, the earliest recording of the mass (in I-Rvat Cap. Sist. 51, copied late1487/early 1488) is close in time to a major state event in Maximilian’s life: his coronation as King of the Romans in the spring of 1486 in Aachen. The fact that the second early manuscript source is a fragmentary manuscript (» A-LIb Hs. 529; » C. Medien mehrstimmiger Vokalmusik, Kap. Handschriftliche Quellen zur Missa Salve diva parens) which likely belonged to Maximilian’s circle after his return to the Empire (c. 1490–1492), further supports this connection. These circumstances justify the hypothesis that Obrecht may well have composed Missa Salve diva parens in the context of Maximilian I’s royal coronation.

Emperor Friedrich III and Archduke Maximilian 1485/86: Reunion – Royal Election – Journey to the Netherlands

We are well informed about the long-awaited royal coronation, which was meticulously prepared by Maximilian and his court, through the chronicle of the Burgundian court secretary Jean Molinet. It ultimately became one of the most splendid moments in Maximilian’s life. As early as autumn 1485, the extremely elaborate travel preparations had begun.[9]

Maximilian had not seen his father, Emperor Friedrich III, since leaving for the Netherlands eight years earlier. Their first meeting since then, along with their respective chapels, took place in Aachen: Maximilian arrived there on December 12, and Friedrich III on December 22, 1485. Christmas was celebrated with several masses in Aachen Cathedral, and the rulers visited the church’s sacred relics.[10]

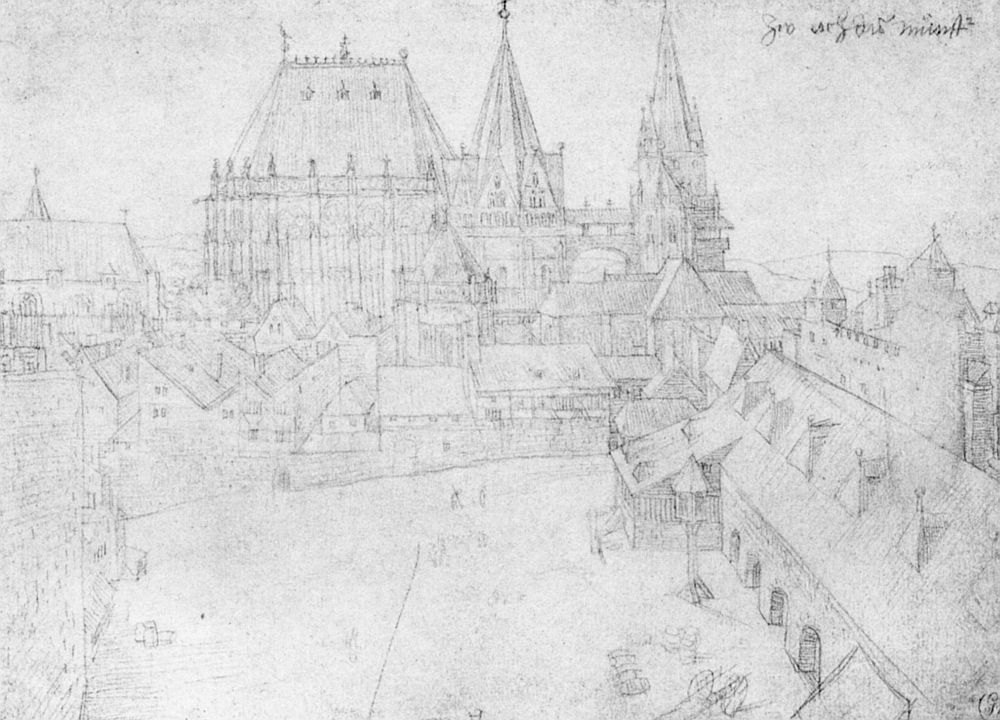

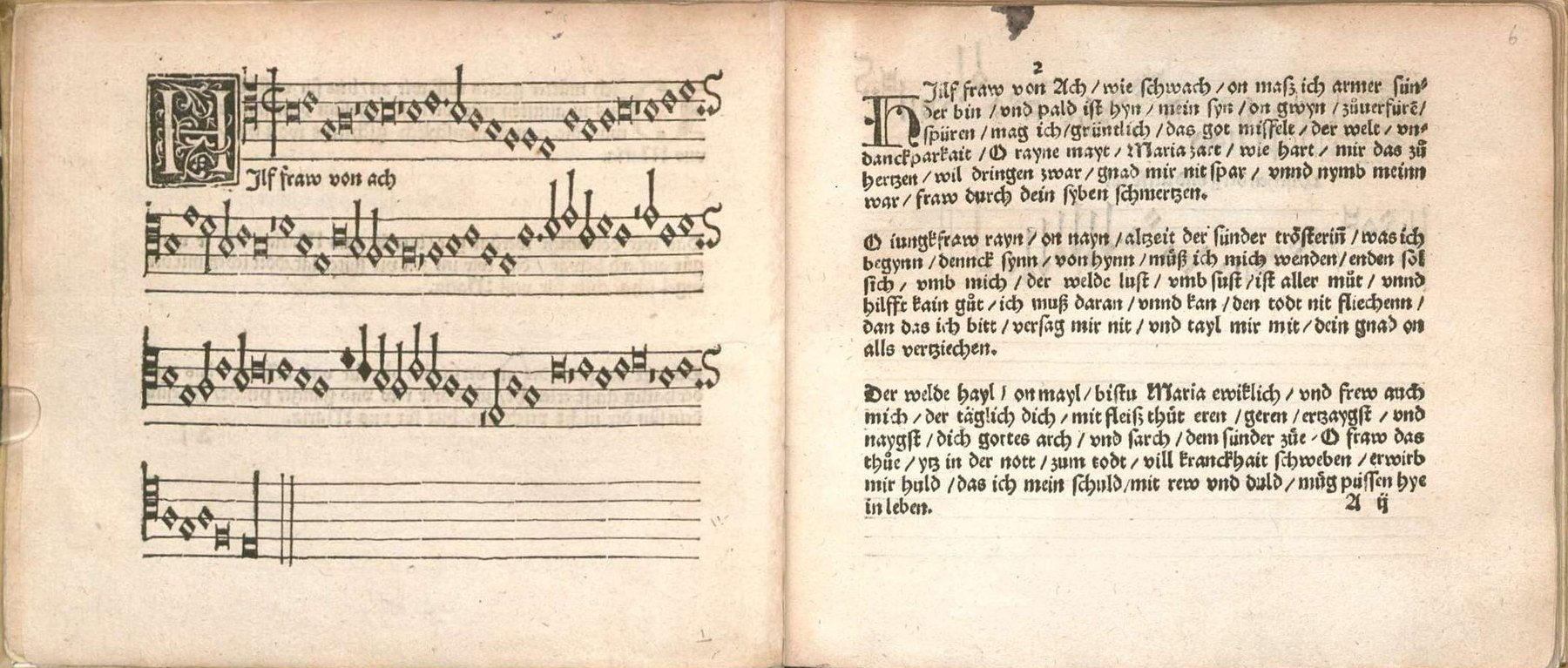

Aachen Cathedral (» Abb. Das Münster von Aachen) was chosen for the staged reunion as a location of both spiritual and political significance. On the one hand, the cathedral was one of the largest pilgrimage centres of its time: among its most outstanding relics were, notably, the robe supposedly worn by Mary at Christ’s birth and the swaddling clothes of the infant Jesus.[11] The song Hilf, Frau von Ach (» Abb. Hilf, Frau von Ach), part of Maximilian’s court chapel repertoire,[12] reflects this context: the “poor sinner” invokes the Holy Mother of God of Aachen (“Ach”). The homorhythmic declamation, interspersed with pauses, of all voices at the conclusion—“[Gnad mir nit] spar || und nimm mein wahr || Frau, durch dein sieben Schmerzen”—resembles similarly evocative musical gestures found in other songs from contemporary religious practice, such as Maria zart (» Hörbsp. ♫ Maria zart).

Additionally, Aachen Cathedral, built under Charlemagne, was the traditional site for royal coronations in the Holy Roman Empire. This made the location of the meeting profoundly symbolic: only recently (around October/November 1485) Emperor Friedrich III, in light of the precarious political situation in the empire, decided to elevate his son Maximilian to kingship during his lifetime, a goal Maximilian himself had pursued for years.[13]

Frederick and Maximilian met at Cologne on 4 January 1486. They celebrated the Feast of the Epiphany (January 6, the Feast of the Three Kings), again symbolically, in Cologne, where the relics of the Three Magi were venerated. On 16 February 1486, Maximilian was finally elected king by the prince-electors at the Imperial Diet in Frankfurt, thereby confirming him as the designated successor to the imperial throne. This was followed by the symbolic enthronement upon the altar.[14]

After Easter, the entourage returned to Aachen, where an exceptionally lavish Adventus (ceremonial entry into the city) was staged. Alongside the group of monastic clergy and Aachen citizens carrying their “Achhörner” (“Aachen horns”), trumpeters and drummers accompanied the relic of Charlemagne, which was carried under a canopy.[15] The grand coronation ceremony in Aachen Cathedral and Charlemagne’s Palatine Chapel took place on 9 April 1486. On the following day, as at Christmas 1485, Maximilian again saw the relics, this time in the presence of his father.[16]

Yet the months-long celebrations, receptions, and elaborately arranged religious ceremonies did not end there. From 20 July to 16 October, 1486, the newly crowned King Maximilian travelled with his father and his son, Archduke Philip, accompanied by their three courts (and likely their chapels as well), at Maximilian’s expense, through the cities and provinces of the Netherlands. They spent extended periods in Leuven, Brussels, Ghent, and Bruges (1–13 August), where they received a triumphant reception.[17] Additionally, after several temporary separations due to Maximilian’s need to engage in the southern war zone, they stayed in Lille and Antwerp. The emperor’s presence greatly enhanced Maximilian’s prestige in the Netherlands while simultaneously serving as a demonstration of power against France, the ongoing adversary in the conflict.[18] The costs of this highly elaborate coronation journey, which lasted almost an entire year, were immense.

“Multiple Meanings” in the Text and Music of the Missa Salve diva parens

In some manuscripts, the tenor voice of Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens includes a text in red ink that does not belong to the ordinary of the mass (» Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens). Such textual annotations usually indicate the material—that is, a liturgical, sacred, or secular melody—on which a cantus firmus mass is based. However, with the characteristically titled Salve diva parens (which is also noted as the mass’s heading in A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495), we face a mystery: this prominently indicated text is not preserved elsewhere.[19]

Text Salve diva parens

Salve diva parens prolis amoenae,

Hail, divine mother of the lovely offspring,

Aeternis meritis virgo sacrata,

through eternal merits, sacred virgin,

Qua lux vera, deus, fulsit in orbem

through whom the true light, God, shone upon the world

Et carnem subiit rector Olympi.

and the ruler of Olympus took on flesh.

The first half of the verse follows the metrical pattern of a hexameter, resembling the opening words of the Introitus of the Marian Mass Salve sancta parens. Its rare, post-classical meter places it within the context of humanist poetry.[20] The content also references Salve sancta parens. Notably, however, the opening words differ in the use of “diva” instead of “sancta.” “Diva” is not a typical epithet for Mary, unlike “sancta” or “vera.” Here, the divine mother is explicitly addressed, followed by her divine son—invoking not only Christian but also mythological connotations, such as Virgil’s Aeneid.

Surprisingly, the ruler is addressed with the non-Christian imagery of the “ruler of Olympus” (“rector Olympi”), intertwining the expected meaning of “Jesus” with that of “Jupiter” (the actual “rector Olympi”[21]). Likewise, the choice of “Olympi” rather than the more customary Christian alternative “caeli” is significant.

Thus, Salve diva parens is a text that formally and thematically adopts liturgical motifs but is not liturgical itself; rather, it is a sophisticated new creation (» I. Humanisten). Christian and mythological elements are interwoven.[22] The text, describing the world’s enlightenment through the incarnation of the ruler, refers not only to God and Christ but also to the ruler in general. This peculiarity is as difficult to reconcile with a pure Marian Mass as is the text’s highly artistic meter.

Just as the Neo-Latin text is deliberately ambiguous (blending Christian-liturgical and mythological-classical terms), the musical construction is similarly double-layered. Some scholars have noted that, while the first notes of the tenor in each mass movement seem to follow a fixed cantus firmus melody, the composition does not consistently maintain it. Instead, the mass appears largely freely composed, employing purely musical construction principles (e.g., motivic-additive structures[23] and cyclic turns; » Hörbsp. ♫ Qui cum Patre).

Both the resonating text and the musical structure of Salve diva parens operate on the principle of the superimposition of two levels. Comparable approaches have been known in the context of ruler representation since the Middle Ages and reached a particular height under Maximilian I (see the chapter “Multiple Meanings”: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler).

“Multiple Meanings”: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler

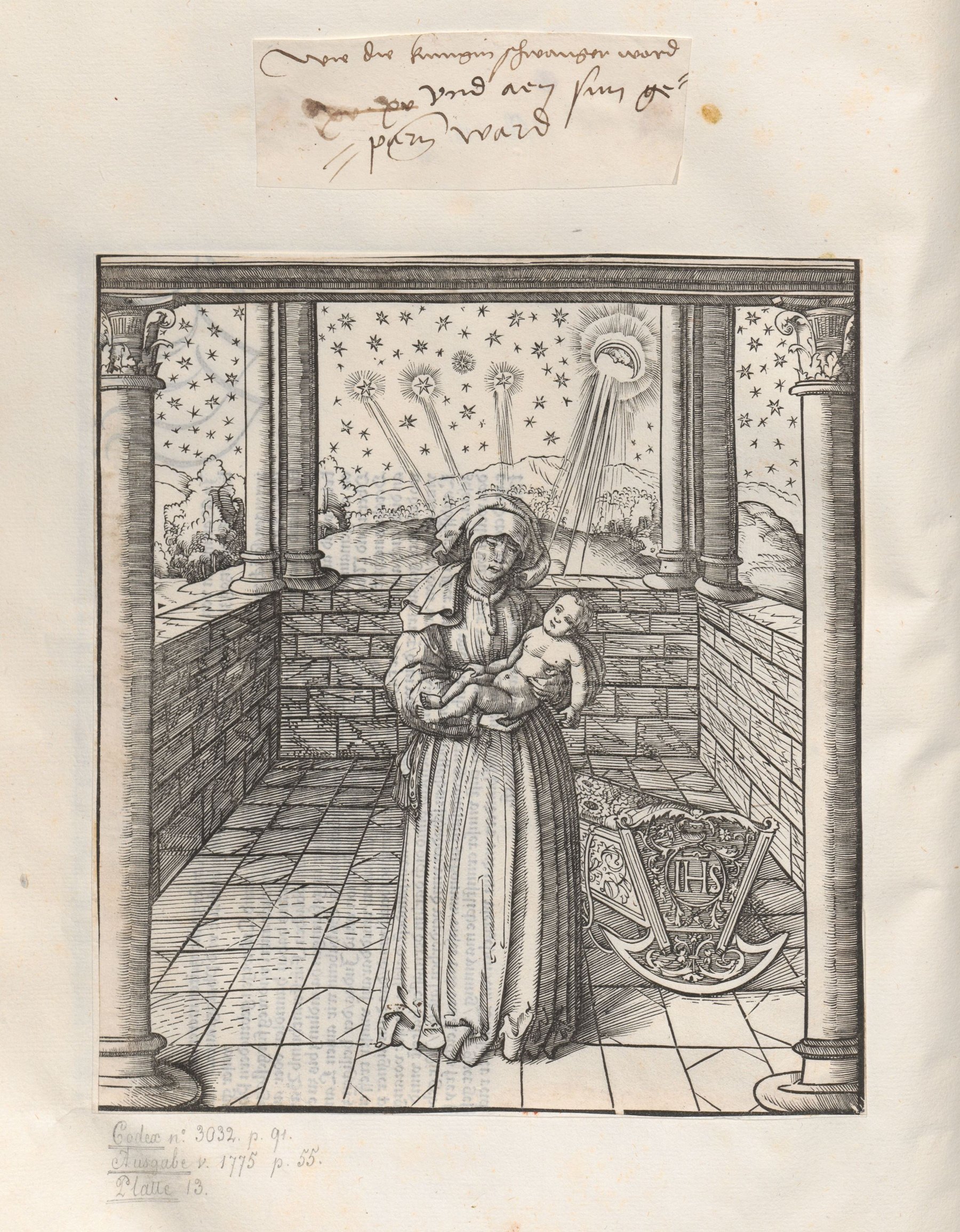

In the Weißkunig (White or Wise King), the German-language (auto-)biography co-authored by Maximilian himself, numerous passages are modeled after the stories of Jesus’s life. Maximilian is staged as a god-like world Saviour—a notion that aligns with the traditional ruler legitimization (that all rightful kings and emperors are chosen and appointed by God[24]) but which in its vividness and intensity goes significantly beyond this tradition. For example, the depiction of the Weißkunig’s birth follows the model of the Gospel of Luke: a brightly shining comet appears as a special “sign and revelation,” and the mother gives birth almost without pain.[25]

The corresponding woodcut makes this particularly evident, as it merges the birth of Christ with that of Maximilian (» Abb. Geburt des Jungen Weißkunig). Although it clearly depicts Maximilian’s (alias Weißkunig’s) birth, the cradle bears the inscription “IHS”—the nomen sacrum for “Jesus”—and the caption states: “How the queen became pregnant and gave birth to a son.”[26] Through this equation, this natural linkage to the sacred sphere, the secular ruler gains divine legitimacy.

Even in the Latin biography written by Joseph Grünpeck, the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani,[27] Maximilian’s divine mission is highlighted from his birth. In the pen drawing The First Bath of the Little Maximilian, attributed to Albrecht Altdorfer, the newborn stands in the bath tub, beside him his cradle, again marked with “IHS”.”[28] Throughout the descriptions of Maximilian’s childhood and life story in the Weißkunig, the Historia, and the Theuerdank, many further parallels to episodes from Jesus’ life are drawn—ranging from the unborn child leaping in the mother’s womb to the carrying of the cross.[29] Art historian Larry Silver expresses his amazement: “What is so impressive […] is the equation of Maximilian with Christ himself, of his mother with Mary, and of his baptizer with Simeon.”[30]

While many of Maximilian’s ancestors were only gradually invoked and staged during his lifetime, the parallel “Maximilian as Jesus” was already well established during the Burgundian period. Jean Molinet, the Burgundian court chronicler, made it his particular concern to legitimize the foreign-born young ruler as a saviour through elaborate rhetorical means. In his Chroniques, he cast Maximilian’s courtship in the words of the Annunciation from the Bible, proclaiming the arrival of the Redeemer: he addresses Duchess Mary with “Tu es bien heurée entre les femmes” (“You are fortunate among women”), and she responds accordingly as the handmaid of the Lord. Maximilian came to Burgundy as lux in tenebris (“light in darkness”), against the resistance of evil forces.[31] (cf. the 3rd line of the text Salve diva parens: “Qua lux vera, deus, fulsit in orbem”; see Kap. „Mehrfacher Sinn“ von Text und Musik der Missa Salve diva parens).

In the context of the royal coronation, this stylization was of particular relevance for Molinet regarding legitimacy. He staged Maximilian as the Messiah: “The Highest King of Kings, the ruler of the world, has graciously looked upon us and, to save us from our captivity, has chosen a pure maiden named Mary, of royal lineage, like a lily among thorns, and from his sovereign throne has sent down to us the Archduke Maximilian, his most beloved son, who, finding himself in this miserable vale of tears full of enemies, has banished the foes with the help of well-meaning people […]”[32] What follows is a rich collection of images from Jesus’ life and passion, among them: Maximilian bore the cross, suffered great anguish, rose again, ascended with supreme glory to his parents and friends, and said to his father: “Pater, manifestavi nomen tuum hominibus” (“I have manifested thy name unto men”) (John 17:6).[33]

Molinet concluded his report on the royal coronation (including the inaugural visits to the Flemish cities) with an extensive chapter titled Le Paradis Terrestre, which is considered the centrepiece of his Chroniques.[34] Here, he offers a comprehensive interpretation of events, comparing the Emperor (Frederick III), the King (Maximilian), and his son Philip to the Holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—though the latter parallel was, admittedly, the most challenging. Philip, Molinet suggests, moved between father and son and flew like the Holy Spirit. But he did not stop there: Molinet’s comparison of Emperor, King, and Duke to the Trinity was embedded in a poetic vision of society, the ciel impérial (“imperial heaven”), where the Moon, Mercury, and Venus symbolized peasants, commerce, and the bourgeoisie. The Sun, central among the planets, was equated with the Church and the ancient church fathers and philosophers; Mars with the nobility; Jupiter, as the son of Saturn and the brightest planet, with the Roman kings, particularly Maximilian; and finally, Saturn, the most distant planet, with the Emperor.[35]

In multiple ways, Molinet’s imagery intertwines sacred and mythical roles for Maximilian: on the one hand, he draws parallels between Emperor, King, and Duke with God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and stylizes the Burgundian Duchess Mary as an analogue to the Mother of God. On the other hand, he compares the social order to the celestial order. The association with “Jupiter,” as demonstrated earlier, resonates in the phrase “rector orbis” in the text of Salve diva parens and frequently reappears in Maximilian panegyrics, most notably in Conrad Celtis’ ode from 1487, in which he celebrates Frederick III’s coronation as a poet laureate, and characterizes the shared rule of Emperor and King.[36]

Thus, Molinet’s Chroniques laid the foundation for what Maximilian would propagate as his self-image throughout his life with particular vigour, though in continuity with the medieval tradition of portraying the secular ruler as christomimetes. According to Hermann Wiesflecker, Maximilian repeatedly compared “the burdens and sorrows of his office with the sufferings of Christ, or with the Egyptian Horus and Osiris, or with Hercules […]. Under the image of Hercules Germanicus, the Emperor was venerated as the saviour of Germany. The divine right of kings, divine sonship, and unity with God apparently made no significant distinction in his religious outlook. The rebirth of man into godlikeness corresponded as much to humanist ideas as the ‘deification’ did to the thoughts of German mysticism.”[37]

Praises of Mary, God, and the Ruler in the Missa Salve diva parens

If one transfers the parallelization of Jesus and Maximilian in their roles as the saviour of the world and bringer of peace, as documented in reports, writings, and images, to Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens, this Marian mass, which employs the theme of the incarnation of “the ruler of Olympus,” simultaneously becomes a mass for the new King Maximilian.

Amongst the several sources that transmit this mass, the humanistic text Salve diva parens is notably underlaid beneath the notes in a few manuscripts, and all of these are connected to Maximilian, either directly (like A-Wn Mus-Hs. 15495) or indirectly (like the relevant fascicle in » D-LEu Ms. 1494)[38][39] Moreover, the text in these sources is not only transmitted as an incipit—as usually happens for reference to a cantus firmus—but is fully written out syllable by syllable under the musical notation (» Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens). This indicates that it was sung simultaneously with the mass text in the relevant voice during performance. It thus clearly had significance in Maximilian’s context. This text, with its refined meter and the incorporation of non-Christian imagery beyond typical Marian texts, can be understood as an example of the blending technique so characteristic of Maximilian I (according to Jan-Dirk Müller: “multiple meaning”[40]). It can refer not only to the Holy Mother Mary and the incarnation of the Saviour Jesus Christ and his reign, but also to the installation of the new King Maximilian I and his hoped-for role as a bringer of peace in the Burgundian Netherlands (see chapter “Multiple Meanings” in the Text and Music of the Missa Salve diva parens und chapter “Multiple Meanings”: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler).

In the artistic design of the splendid manuscript created for Maximilian » A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495, the two interwoven levels are particularly apparent (» Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens). TThe first association upon viewing the illuminations of the opening double page, which also marks the beginning of the Missa Salve diva parens (A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495, fol. 1v-2r) is certainly Christmas. In the image at the top left (Discantus voice), Mary gives life to the new ruler, Jesus. In the image at the top right (Contratenor voice), Maximilian (depicted in his actual portrait) kneels in reverence to the Mother of God. Above the praying Maximilian, at the top edge of the page, the words “O mater dei memento mei” (“O mother of God, remember me”) are inscribed.[41]

These words, which are not set to music in the mass itself, often serve as a closing phrase in Marian prayers. Through their placement on the individually illuminated opening page, Maximilian personally asked the Blessed Virgin Mary for his salvation. (Iconographically, the kneeling emperor and the kneeling Mary are also mirror images of each other.)

The second interpretive level is conveyed through the placement of Maximilian I’s imperial coat of arms as the tenor initial. Here, Maximilian is not depicted as a person but as a ruler. And it is precisely at this point that the text “Salve diva parens” (which is presumably linked to a cantus firmus melody) appears. This means that Maximilian, as King (at the time when this manuscript was written, Emperor), greets the “diva parens,” the divine mother, who in a metaphorical sense has granted him rule.[42]

Each performance of this mass thus functioned not only as praise for the Virgin Mary and her Son Jesus as ruler of the world, but also as a prayer for the new ruler Maximilian I, as both a person and a king. Notably, in the late Middle Ages, the practice of polyphonic music was seen as a representative, symbolic instrument of power, to which the elaborate maintenance of large chapels and scriptoria, as well as preserved media like the magnificent Alamire choir books, impressively testify.

For his long coronation journey of 1485/86, Maximilian spared no expense or effort (» Kap. Jacob Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens und Erzherzog Maximilian). Given that Maximilian had just brought the estates of the Low Countries to his side and was still at war with France, and that Matthias Corvinus had entered the castle of Vienna shortly before, in the summer of 1485, the newly crowned king evidently felt it necessary to cultivate his reputation and demonstrate his strength and power. The re-establishment of the Burgundian chapel just before the coronation fits in this context. Molinet even reports that the newly established chapel made a great impression on the German rulers.[43] In a situation where Maximilian was to be represented as a legitimate king and future emperor, the chapel thus had an almost state-bearing function.

The context of the coronation celebrations proposed here opens up a new interpretive perspective for Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens. The specific mass celebration for which Obrecht composed the mass remains open and must stay that way. However, two occasions are particularly plausible. It could have been intended for the coronation festivities at the Cathedral of St Mary in Aachen, where the symbolism of the famous Marian church merged with that of the traditional coronation church. Even if Obrecht himself was most likely not present at this ceremony, it is still possible that he was commissioned to write this mass beforehand. Equally plausible is the idea that he composed the mass during the immediate post-coronation journey of Maximilian I and his father Frederick III to the Netherlands, specifically for their stay in the city of Bruges (see Kap. Kaiser Friedrich III. und Erzherzog Maximilian 1485/86: Wiedersehen – Königswahl – Reise in die Niederlande), where Obrecht had been serving as succentor (choir director) at the church of St. Donatian since 13 October 1485.

In the late Middle Ages, music in worship often served not only as praise of God but also simultaneously as praise of the ruler. Both functions equally inspired the composers of the time to create outstanding works of art. Therefore, we should not necessarily expect any stylistic difference between music for the praise of God and music for the praise of rulers, and indeed no such a difference is found in contemporary compositions. This is particularly evident when both spheres are explicitly named in the text, as in Heinrich Isaac’s motet Virgo prudentissima (» D. Isaac und Maximilians Zeremonien, Kap. Komponiertes Herrscherlob: Isaacs Motette Optime divino … pastor) or in Benedictus de Opitiis’ motet Summe laudis o Maria (» D. Musikalische Huldigungsgeschenke, Kap. Gedrucktes mehrstimmiges Herrscher- und Marienlob). Another example of this is Obrecht’s lesser-known composition Omnis spiritus laudet,[44] which encapsulates a series of acclamations and prayer sentences in two- to four-voice music and maintains the same style of setting, whether referring to God the Father and Son, the worldly king, or Mary.[45] I also suspect a connection with Maximilian’s coronation journey to the Netherlands in the summer of 1486 in this composition.

More important than the search for specific occasions of creation seems to be the enquiry after the contexts, goals, and expectations in which a given repertoire was created and received. The attempt to think together, as was customary in the Middle Ages, secular and spiritual spheres from the perspective of a modern listener can open entirely new dimensions of perception.

[1] See Dunning 1970.

[2] Basic principles regarding the symbolic relationship between Cantus firmus material and mass composition can be found in Kirkman 2010. Reinhard Strohm can plausibly connect the creation of two Obrecht masses with foundations in Bruges (Strohm 1985, 40 f., 146 f.). For Obrecht’s Missa Sub tuum presidium, see » J. Körper und Seele.

[3] Roth 1998, especially 46 f., 52 f., 55. From Rome, the Mass likely found its way into the extensive choirbook » I-VEcap 761 in the mid-1490s. For the creation time and circumstances of this manuscript, see Rifkin 2009.

[4] The documents regarding the suspected trip to Rome were compiled by Rob C. Wegman (Wegman 1994, 139–144), although he assumes that the Mass was already present in Rome by that time.

[5] The mass repertoire of the Burgundian court chapel from the 1460s and 1470s can be found in the choirbook » B-Br Ms. 5557 (facsimile: Wegman 1989). The six anonymously transmitted L’homme armé masses in the choirbook » I-Nn Ms. VI E 40 are also likely associated to the Burgundian chapel. The “Alamire Manuscripts,” closely associated with the court, were created during or after the reign of Philip the Handsome (» A-Wn Mus. Hs. 15495).

[6] See Strohm 2009.

[7] A detailed account with names of singers, their positions, and musical qualities can be found in Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 469 f.

[8] The date commonly given is 17 November 1492 (see Fiala 2015, 434); Honey Meconi (Meconi 2003, 20–23) interprets the surviving payment records differently and assumes the transfer took place on September 30, 1495; see also Gasch 2015, especially 363 f.

[9] See the descriptions in Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 469–471; see also Cuyler 1973, 32–35.

[10] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 474.

[12] The song is preserved in two contemporary sources that both reflect the repertoire from Maximilian’s court (» B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst unter Maximilian I.; » B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Liederdrucke): in » D-As Cod. 2° 142a (fol. 69v–70r; the tenor incipit of the otherwise textless notation reads „hilff fraw von Ach“) and in the songbook » Aus sonderer künstlicher art… (Augsburg: Erhard Oeglin 1512), where the song appears second after the Marian hymn Dich mütter gottes rüff wir an.

[13] Wolf 2005, 98–102. Friedrich moved the Reichstag, originally scheduled for December 1485 in Würzburg, to January in Frankfurt am Main.

[14] For the election of Maximilian as king, see in detail Wolf 2005, 100–122, especially 115 f. During the altar installation ceremony, the newly elected king was indeed placed on the altar, the throne of Christ; see in detail Bojcov 2007, 243–314: „Die Altarsetzung […] war Teil der Wahlprozedur und war am besten dazu geeignet, einen aus dem Kreis der mehr oder weniger Gleichen auszusondern und über sie [zu] erheben.“ (Bojcov 2007, 292).

[15] See Schenk 2003, 307–313, 336–338; see also » D. Fürsten und Diplomaten auf Reisen.

[16] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 474 und 511. – The Aachen pilgrimage usually took place every seven years.

[17] Custis 1765, 68 f.; see also Wolf 2005, 191–200.

[19] The reconstruction of the Latin text according to Staehelin 1975, 20–23.

[20] The underlying text, a type of hymn strophe, could represent a humanistic expansion of the Marian hymn O quam glorifica luce coruscas (attributed tp Hucbald of Saint-Amand, 840–930), in the same rare meter (catalectic Asclepiadeus minor), especially since the cantus firmus of the mass, notoriously resistant to reconstruction, seems to show similarities with that in Févin’s Missa O quam glorifica (Strohm 1985, 148).

[21] “Rector” does not appear in the New Testament, but frequently in Ovid, especially concerning Augustus and Jupiter; see Flieger 1993, 67–69.

[22] See Stieglecker 2001, 388–391 et passim; for general information on humanistic veneration of saints, see Flieger 1993, 17–122.

[23] See Wegman 1994, 179–183.

[24] Current historical events have their counterparts in the New Testament, which in turn represent the fulfilment of events from the Old Testament in salvation history. “Thus, a legitimization of the Christian ruler from the Old Covenant takes place, which as already appears as the Carolingian-Franconian period, aappears to have been placed alongside the legitimation from the ancient empire as equally important.” (Cremer 1995, 88 f.).

[25] Maximilian I.: Weißkunig 1888, 47–49.

[26] Müller 1982, 147 f.; Dietl 2009, 37–40.

[27] Ca. 1513/14;Maximilian dictated the book in part and corrected it by hand.

[28] » A-Whh Hs. Blau 9 Cod. 24, fol. 38r; see also Silver 2008, 136 f., including the illustration.

[29] Cremer 1995, especially 88–99; Wiesflecker 1971, 65–67.

[30] Silver 2008, 137.

[31] See also Müller 1982, 147 f., 333; Wiesflecker 1971, 121, 131 f.; Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 338.

[32] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 535 (in free translation).

[33] “I have revealed Your name to the people whom You gave Me from the world.” With these words, Christ Himself (here impersonated by Maximilian) declares whose true Son He is, according to the Gospel of John.

[34] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 529–539; see also Frieden 2013; Thiry 1990, 268–270.

[35] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 533–539; see also Müller 1982, 147.

[36] Ode 1,1 Caesar magnificis; see also Mertens 2000, 74 f.; foundational works on this topic: Tanner 1993; Seznec 1953.

[37] Wiesflecker 1991, 355 f.

[38] In the so-called Apel Codex (» D-LEu Ms. 1494), it seems that repertoire from Maximilian’s court was repeatedly included, mediated through the repertoire of the court chapel of Frederick the Wise of Electoral Saxony, who was in close contact with Maximilian from at least 1490; see Lodes 2002, 256–258.

[39] The text might also have been included in the manuscript » A-LIb Hs. 529 (“Linzer Fragments”), but only a small amount of music is preserved there.

[40] Regarding the “multiple meaning” in late medieval poetry, see Wehrli 1984, especially 236–270; Müller 1982, 146–148, also 124–129.

[41] The only other contemporary musical manuscript I know that begins with the words “[O Mater dei] memento mei” is the splendid manuscript B-Br 228, also produced in Petrus Alamire’s workshop. There, the words are attributed to the praying Archduchess Margaret, Maximilian’s daughter; see the illustration Blackburn 1997, 596 f., and Blackburn 1999, 188.

[42] See, among others, Borghetti 2015; Borghetti 2008, especially 208–214.

[43] “[…] lesquelz, ensamble unis, estoffoyent une très bonne chapelle dont il fut grandement honouré et prisiet des princes d’Alemaigne.” (Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 470).

[44] Edition in Maas 1996, 43–47.

[45] In the text sections, first, forgiveness is requested from the Lord and thanks are given to the almighty King. Then, a prayer is made for “our (worldly) King” (“Pro rege nostro”) that the Lord may preserve him and that he may not fall into the hands of the enemies, and that the souls of the faithful may rest in peace. After a spoken “Our Father,” a final prayer to the Virgin Mary is sung, who carried the Son of the eternal Father. The musical petitions to God, for the king, and for Mary are concluded with a four-part “Amen” in each case. The music follows the rhythmic structure (in both the two- and four-part sections) exactly as per the text declamation (see Edwards 2011, 62 f.), and the largely homorhythmic, simple setting does not change throughout the piece, remaining the same for all three thematic areas.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Birgit Lodes: “„Mehrfacher Sinn“: Jacob Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens und die Königskrönung Maximilians”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/mehrfacher-sinn-jacob-obrechts-missa-salve-diva-parens-und-die-konigskronung-maximilians> (2017).