Printed Polyphonic Praises of the Ruler and the Virgin Mary

During his visit to the Netherlands as the newly proclaimed emperor (» Ch. On the Repertoire of the Manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495), Maximilian also paid a splendid visit to the city of Antwerp in September 1508, ahead of negotiations with France. He first invoked the Holy Spirit for guidance, then turned to the Virgin Mary, seeking her protection for his actions with the motet Sub tuum presidium (“Under your protection and shelter…”), a polyphonic setting of an ancient Marian prayer that evidently held special significance for Maximilian (» J. Body and Soul). During this visit, his grandson Charles (» D. Musik für Kaiser Karl V.) was also named Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire.

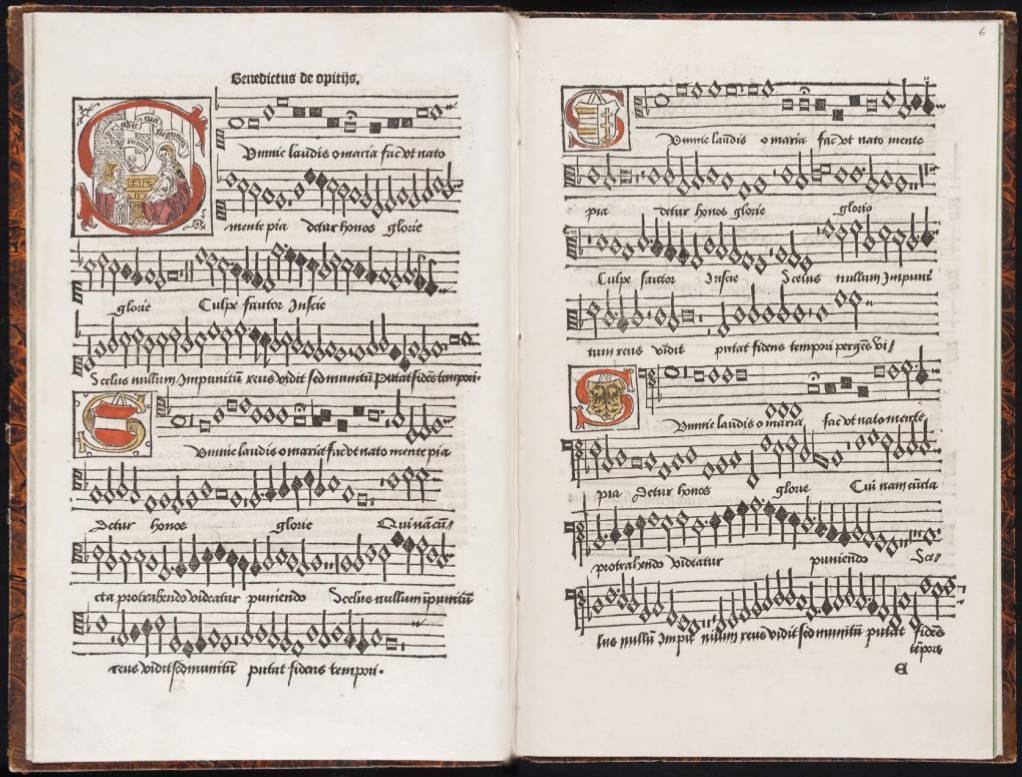

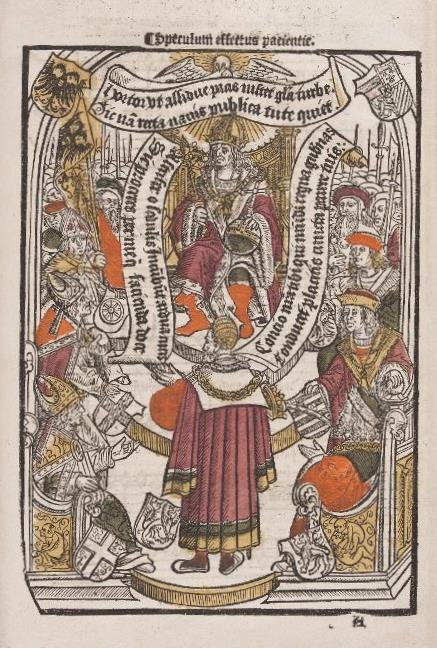

When, in February 1515, the accession of the fifteen-year-old Charles as Duke of Burgundy was staged in Antwerp, the city took the opportunity to commemorate and historicise the last major visit of Maximilian and Charles (that of 1508) in a media-savvy way. A forty-page printed work was produced titled: » Unio pro co[n]servatio[n]e rei publice / Lofzangen ter ere van Keizer Maximiliaan en zijn kleinzoon Karel den Vijfden (Union for the Preservation of the Commonwealth / Songs of Praise in Honor of Emperor Maximilian and His Grandson Charles V). This publication included praise of rulers, God, and the Virgin Mary in a wide variety of textual forms, images, and music:[15] laudatory poems, humanist letters, prayers, full-page woodcuts, and the two motets Sub tuum presidium and Summe laudis o Maria. This edition, issued by the Antwerp printer Jan de Gheet in 1515, is the earliest known print of polyphonic music from the Low Countries.[16] The 17 pages with notes – as in A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 in choirbook arrangement – and text are produced in block printing (woodcut) (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria).

The printed work documents the events in Antwerp in 1508 and focuses on Maximilian’s achievements – his efforts for peace in the empire, unity among the princes, and the promotion of the common good[17]) – which he accomplished through the intercession and support of the Virgin Mary (see, for example, » Abb. Maximilian I. und Kurfürsten). The editions reflects a widely held concept of rulership at the time, vividly illustrated in the initial letter at the beginning of the Discantus part of the motet Summe laudis o Maria (Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Initial): Maximilian is depicted as ruler of the world, entrusted with his high office by God – just as many other rulers were. The Holy Spirit sends down its rays upon him, and Mary provides her indispensable support in the execution of his heavy responsibilities.

The centerpiece of the tribute print is the second motet, Summe laudis o Maria, whose text was written by Petrus de Opitiis, the brother of the composer of both motets, Benedictus de Opitiis (*c. 1476 – †1524).[18] The text of the motet is paraphrased and interpreted section by section in the print, and the motet is also introduced by a Latin poem that makes clear that the motet’s line of thought forms the conceptual foundation of the entire publication.

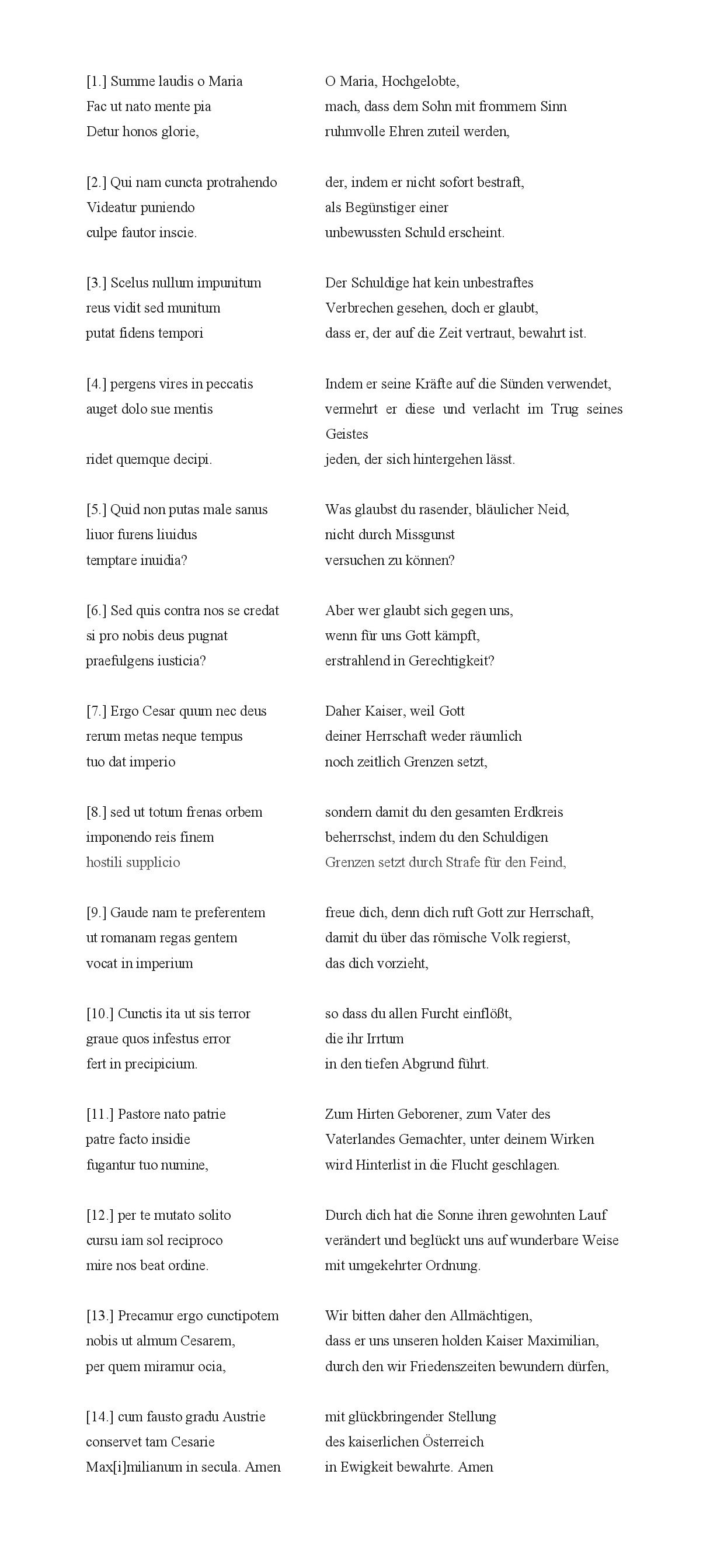

The text of Summe laudis (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Text) begins with a great praise of Mary, and then, through various expressions, addresses the legitimacy of Maximilian as emperor.[19] This was a significant theme in its historical context, since his rightful coronation in Rome had been prevented. The text culminates in an extended praise of the emperor.[20] The structure of the text – with the Marian praise first, followed by the praise of the ruler – thus mirrors that of Heinrich Isaac’s motet Virgo prudentissima (» D. Kap. Musik für den Konstanzer Reichstag 1507).

Visually, the intertwining of Marian devotion and political-secular themes in the Antwerp edition is emphasised by the initial of the motet Summe laudis, which shows Emperor Maximilian singing the words “We flee to you under your protection” (“Sub tuum presidium ad te confugimus”, > Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, » Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Initiale), thereby placing himself under Mary’s protection. Remarkably, the text suggests that the ‘Son of Mary’ is not only Jesus (who is never mentioned by name), but also Maximilian himself, who is to be praised (» D. Ch. ‘Multiple Meanings’: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler).

In his four-voice motet, Benedictus de Opitiis followed the structure of the text and placed clear polyphonic cadences at the end of nearly every textual unit. As was typical for the motet genre at the time, he composed a strongly imitative four-voice texture, and he highlighted certain passages through homorhythmic voice-leading to enhance textual clarity. Examples include the resonant opening section (“Summe laudis o Maria […] glorie”), the encouragement to fight with trust in God (sixth textual section), and the final two sections (13 and 14), where musical punctuation after the words “cunctipotem” and “Maximilianum” emphasises the pleas that God Almighty may preserve the peace-bringing Emperor Maximilian and the Austrian empire for eternity.

[15] The edition was produced in two editions (one with a Dutch summary, the other with a Latin summary) and is available as a facsimile with commentary: Nijhoff 1925, with a transcription of the two motets by Charles Van den Borren as an appendix. See also Schreurs 2001 and Wouters/Schreurs 1995. For a complete digital version of the Latin edition, see: http://depot.lias.be/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE4756261.

[16] A musical edition with the imperial coat of arms and that of the Margraviate of Antwerp had already been produced earlier in Antwerp: » Principium et ars tocius musice, Antwerpen: Jost de Negker (c. 1500–1508). However, this is a depiction of the Guidonian Hand with mensural notation and commentary, not a polyphonic composition. See Schreurs/Van der Stock 1997; a facsimile is also found on 173.

[17] Schlegelmilch 2011, especially 443–447.

[18] Benedictus held the position of organist at the Church of Our Lady in Antwerp from 1512 to 1516 and later moved to the English royal court. Only these two compositions by him are known.

[19] Victoria Panagl particularly highlights the lines “Ergo Cesar quum nec deus / rerum metas neque tempus / tuo dat imperio” (7th stanza; “Therefore, Caesar, since God sets neither spatial nor temporal limits to your rule”), which, as a Virgilian quotation, strongly emphasise Maximilian’s claim to power (as successor to the Roman Empire): In the Aeneid (1.278: “his ego non metas rerum nec tempora pono”), Jupiter speaks these words, looking ahead to the glorious rulers of the Roman Empire (see Panagl 2004, especially 73–81, here 78).

[20] See Dunning 1970, 61–64.