“Multiple Meanings”: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler

In the Weißkunig (White or Wise King), the German-language (auto-)biography co-authored by Maximilian himself, numerous passages are modeled after the stories of Jesus’s life. Maximilian is staged as a god-like world Saviour—a notion that aligns with the traditional ruler legitimization (that all rightful kings and emperors are chosen and appointed by God[24]) but which in its vividness and intensity goes significantly beyond this tradition. For example, the depiction of the Weißkunig’s birth follows the model of the Gospel of Luke: a brightly shining comet appears as a special “sign and revelation,” and the mother gives birth almost without pain.[25]

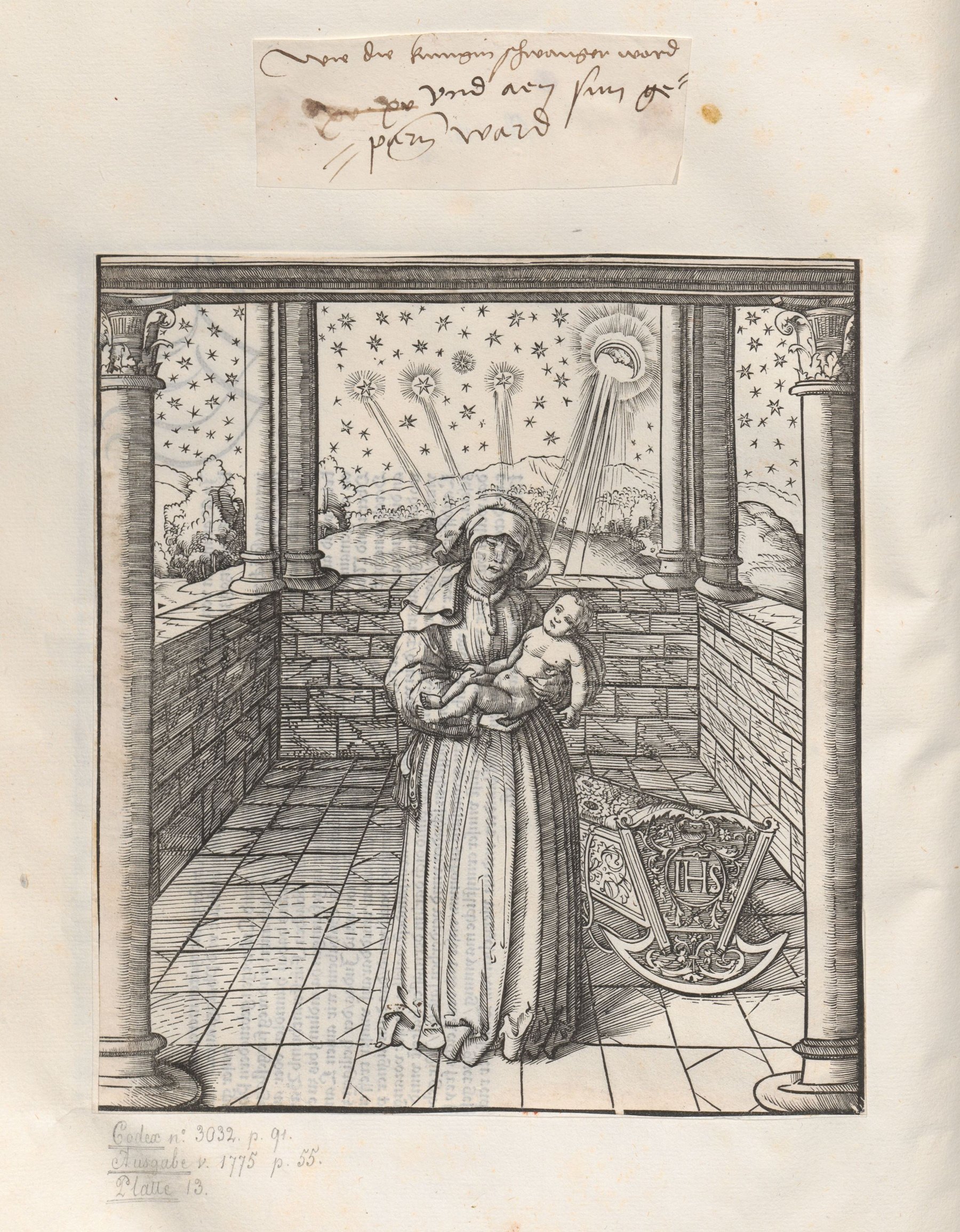

The corresponding woodcut makes this particularly evident, as it merges the birth of Christ with that of Maximilian (» Abb. Geburt des Jungen Weißkunig). Although it clearly depicts Maximilian’s (alias Weißkunig’s) birth, the cradle bears the inscription “IHS”—the nomen sacrum for “Jesus”—and the caption states: “How the queen became pregnant and gave birth to a son.”[26] Through this equation, this natural linkage to the sacred sphere, the secular ruler gains divine legitimacy.

Even in the Latin biography written by Joseph Grünpeck, the Historia Friderici et Maximiliani,[27] Maximilian’s divine mission is highlighted from his birth. In the pen drawing The First Bath of the Little Maximilian, attributed to Albrecht Altdorfer, the newborn stands in the bath tub, beside him his cradle, again marked with “IHS”.”[28] Throughout the descriptions of Maximilian’s childhood and life story in the Weißkunig, the Historia, and the Theuerdank, many further parallels to episodes from Jesus’ life are drawn—ranging from the unborn child leaping in the mother’s womb to the carrying of the cross.[29] Art historian Larry Silver expresses his amazement: “What is so impressive […] is the equation of Maximilian with Christ himself, of his mother with Mary, and of his baptizer with Simeon.”[30]

While many of Maximilian’s ancestors were only gradually invoked and staged during his lifetime, the parallel “Maximilian as Jesus” was already well established during the Burgundian period. Jean Molinet, the Burgundian court chronicler, made it his particular concern to legitimize the foreign-born young ruler as a saviour through elaborate rhetorical means. In his Chroniques, he cast Maximilian’s courtship in the words of the Annunciation from the Bible, proclaiming the arrival of the Redeemer: he addresses Duchess Mary with “Tu es bien heurée entre les femmes” (“You are fortunate among women”), and she responds accordingly as the handmaid of the Lord. Maximilian came to Burgundy as lux in tenebris (“light in darkness”), against the resistance of evil forces.[31] (cf. the 3rd line of the text Salve diva parens: “Qua lux vera, deus, fulsit in orbem”; see Kap. „Mehrfacher Sinn“ von Text und Musik der Missa Salve diva parens).

In the context of the royal coronation, this stylization was of particular relevance for Molinet regarding legitimacy. He staged Maximilian as the Messiah: “The Highest King of Kings, the ruler of the world, has graciously looked upon us and, to save us from our captivity, has chosen a pure maiden named Mary, of royal lineage, like a lily among thorns, and from his sovereign throne has sent down to us the Archduke Maximilian, his most beloved son, who, finding himself in this miserable vale of tears full of enemies, has banished the foes with the help of well-meaning people […]”[32] What follows is a rich collection of images from Jesus’ life and passion, among them: Maximilian bore the cross, suffered great anguish, rose again, ascended with supreme glory to his parents and friends, and said to his father: “Pater, manifestavi nomen tuum hominibus” (“I have manifested thy name unto men”) (John 17:6).[33]

Molinet concluded his report on the royal coronation (including the inaugural visits to the Flemish cities) with an extensive chapter titled Le Paradis Terrestre, which is considered the centrepiece of his Chroniques.[34] Here, he offers a comprehensive interpretation of events, comparing the Emperor (Frederick III), the King (Maximilian), and his son Philip to the Holy Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—though the latter parallel was, admittedly, the most challenging. Philip, Molinet suggests, moved between father and son and flew like the Holy Spirit. But he did not stop there: Molinet’s comparison of Emperor, King, and Duke to the Trinity was embedded in a poetic vision of society, the ciel impérial (“imperial heaven”), where the Moon, Mercury, and Venus symbolized peasants, commerce, and the bourgeoisie. The Sun, central among the planets, was equated with the Church and the ancient church fathers and philosophers; Mars with the nobility; Jupiter, as the son of Saturn and the brightest planet, with the Roman kings, particularly Maximilian; and finally, Saturn, the most distant planet, with the Emperor.[35]

In multiple ways, Molinet’s imagery intertwines sacred and mythical roles for Maximilian: on the one hand, he draws parallels between Emperor, King, and Duke with God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and stylizes the Burgundian Duchess Mary as an analogue to the Mother of God. On the other hand, he compares the social order to the celestial order. The association with “Jupiter,” as demonstrated earlier, resonates in the phrase “rector orbis” in the text of Salve diva parens and frequently reappears in Maximilian panegyrics, most notably in Conrad Celtis’ ode from 1487, in which he celebrates Frederick III’s coronation as a poet laureate, and characterizes the shared rule of Emperor and King.[36]

Thus, Molinet’s Chroniques laid the foundation for what Maximilian would propagate as his self-image throughout his life with particular vigour, though in continuity with the medieval tradition of portraying the secular ruler as christomimetes. According to Hermann Wiesflecker, Maximilian repeatedly compared “the burdens and sorrows of his office with the sufferings of Christ, or with the Egyptian Horus and Osiris, or with Hercules […]. Under the image of Hercules Germanicus, the Emperor was venerated as the saviour of Germany. The divine right of kings, divine sonship, and unity with God apparently made no significant distinction in his religious outlook. The rebirth of man into godlikeness corresponded as much to humanist ideas as the ‘deification’ did to the thoughts of German mysticism.”[37]

[24] Current historical events have their counterparts in the New Testament, which in turn represent the fulfilment of events from the Old Testament in salvation history. “Thus, a legitimization of the Christian ruler from the Old Covenant takes place, which as already appears as the Carolingian-Franconian period, aappears to have been placed alongside the legitimation from the ancient empire as equally important.” (Cremer 1995, 88 f.).

[25] Maximilian I.: Weißkunig 1888, 47–49.

[26] Müller 1982, 147 f.; Dietl 2009, 37–40.

[27] Ca. 1513/14;Maximilian dictated the book in part and corrected it by hand.

[28] » A-Whh Hs. Blau 9 Cod. 24, fol. 38r; see also Silver 2008, 136 f., including the illustration.

[29] Cremer 1995, especially 88–99; Wiesflecker 1971, 65–67.

[30] Silver 2008, 137.

[31] See also Müller 1982, 147 f., 333; Wiesflecker 1971, 121, 131 f.; Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 338.

[32] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 535 (in free translation).

[33] “I have revealed Your name to the people whom You gave Me from the world.” With these words, Christ Himself (here impersonated by Maximilian) declares whose true Son He is, according to the Gospel of John.

[34] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 529–539; see also Frieden 2013; Thiry 1990, 268–270.

[35] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 533–539; see also Müller 1982, 147.

[36] Ode 1,1 Caesar magnificis; see also Mertens 2000, 74 f.; foundational works on this topic: Tanner 1993; Seznec 1953.

[37] Wiesflecker 1991, 355 f.

[1] See Dunning 1970.

[2] Basic principles regarding the symbolic relationship between Cantus firmus material and mass composition can be found in Kirkman 2010. Reinhard Strohm can plausibly connect the creation of two Obrecht masses with foundations in Bruges (Strohm 1985, 40 f., 146 f.). For Obrecht’s Missa Sub tuum presidium, see » J. Körper und Seele.

[3] Roth 1998, especially 46 f., 52 f., 55. From Rome, the Mass likely found its way into the extensive choirbook » I-VEcap 761 in the mid-1490s. For the creation time and circumstances of this manuscript, see Rifkin 2009.

[4] The documents regarding the suspected trip to Rome were compiled by Rob C. Wegman (Wegman 1994, 139–144), although he assumes that the Mass was already present in Rome by that time.

[5] The mass repertoire of the Burgundian court chapel from the 1460s and 1470s can be found in the choirbook » B-Br Ms. 5557 (facsimile: Wegman 1989). The six anonymously transmitted L’homme armé masses in the choirbook » I-Nn Ms. VI E 40 are also likely associated to the Burgundian chapel. The “Alamire Manuscripts,” closely associated with the court, were created during or after the reign of Philip the Handsome (» A-Wn Mus. Hs. 15495).

[6] See Strohm 2009.

[7] A detailed account with names of singers, their positions, and musical qualities can be found in Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 469 f.

[8] The date commonly given is 17 November 1492 (see Fiala 2015, 434); Honey Meconi (Meconi 2003, 20–23) interprets the surviving payment records differently and assumes the transfer took place on September 30, 1495; see also Gasch 2015, especially 363 f.

[9] See the descriptions in Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 469–471; see also Cuyler 1973, 32–35.

[10] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 474.

[12] The song is preserved in two contemporary sources that both reflect the repertoire from Maximilian’s court (» B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst unter Maximilian I.; » B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Liederdrucke): in » D-As Cod. 2° 142a (fol. 69v–70r; the tenor incipit of the otherwise textless notation reads „hilff fraw von Ach“) and in the songbook » Aus sonderer künstlicher art… (Augsburg: Erhard Oeglin 1512), where the song appears second after the Marian hymn Dich mütter gottes rüff wir an.

[13] Wolf 2005, 98–102. Friedrich moved the Reichstag, originally scheduled for December 1485 in Würzburg, to January in Frankfurt am Main.

[14] For the election of Maximilian as king, see in detail Wolf 2005, 100–122, especially 115 f. During the altar installation ceremony, the newly elected king was indeed placed on the altar, the throne of Christ; see in detail Bojcov 2007, 243–314: „Die Altarsetzung […] war Teil der Wahlprozedur und war am besten dazu geeignet, einen aus dem Kreis der mehr oder weniger Gleichen auszusondern und über sie [zu] erheben.“ (Bojcov 2007, 292).

[15] See Schenk 2003, 307–313, 336–338; see also » D. Fürsten und Diplomaten auf Reisen.

[16] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 474 und 511. – The Aachen pilgrimage usually took place every seven years.

[17] Custis 1765, 68 f.; see also Wolf 2005, 191–200.

[19] The reconstruction of the Latin text according to Staehelin 1975, 20–23.

[20] The underlying text, a type of hymn strophe, could represent a humanistic expansion of the Marian hymn O quam glorifica luce coruscas (attributed tp Hucbald of Saint-Amand, 840–930), in the same rare meter (catalectic Asclepiadeus minor), especially since the cantus firmus of the mass, notoriously resistant to reconstruction, seems to show similarities with that in Févin’s Missa O quam glorifica (Strohm 1985, 148).

[21] “Rector” does not appear in the New Testament, but frequently in Ovid, especially concerning Augustus and Jupiter; see Flieger 1993, 67–69.

[22] See Stieglecker 2001, 388–391 et passim; for general information on humanistic veneration of saints, see Flieger 1993, 17–122.

[23] See Wegman 1994, 179–183.

[24] Current historical events have their counterparts in the New Testament, which in turn represent the fulfilment of events from the Old Testament in salvation history. “Thus, a legitimization of the Christian ruler from the Old Covenant takes place, which as already appears as the Carolingian-Franconian period, aappears to have been placed alongside the legitimation from the ancient empire as equally important.” (Cremer 1995, 88 f.).

[25] Maximilian I.: Weißkunig 1888, 47–49.

[26] Müller 1982, 147 f.; Dietl 2009, 37–40.

[27] Ca. 1513/14;Maximilian dictated the book in part and corrected it by hand.

[28] » A-Whh Hs. Blau 9 Cod. 24, fol. 38r; see also Silver 2008, 136 f., including the illustration.

[29] Cremer 1995, especially 88–99; Wiesflecker 1971, 65–67.

[30] Silver 2008, 137.

[31] See also Müller 1982, 147 f., 333; Wiesflecker 1971, 121, 131 f.; Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 338.

[32] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 535 (in free translation).

[33] “I have revealed Your name to the people whom You gave Me from the world.” With these words, Christ Himself (here impersonated by Maximilian) declares whose true Son He is, according to the Gospel of John.

[34] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 529–539; see also Frieden 2013; Thiry 1990, 268–270.

[35] Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 533–539; see also Müller 1982, 147.

[36] Ode 1,1 Caesar magnificis; see also Mertens 2000, 74 f.; foundational works on this topic: Tanner 1993; Seznec 1953.

[37] Wiesflecker 1991, 355 f.

[38] In the so-called Apel Codex (» D-LEu Ms. 1494), it seems that repertoire from Maximilian’s court was repeatedly included, mediated through the repertoire of the court chapel of Frederick the Wise of Electoral Saxony, who was in close contact with Maximilian from at least 1490; see Lodes 2002, 256–258.

[39] The text might also have been included in the manuscript » A-LIb Hs. 529 (“Linzer Fragments”), but only a small amount of music is preserved there.

[40] Regarding the “multiple meaning” in late medieval poetry, see Wehrli 1984, especially 236–270; Müller 1982, 146–148, also 124–129.

[41] The only other contemporary musical manuscript I know that begins with the words “[O Mater dei] memento mei” is the splendid manuscript B-Br 228, also produced in Petrus Alamire’s workshop. There, the words are attributed to the praying Archduchess Margaret, Maximilian’s daughter; see the illustration Blackburn 1997, 596 f., and Blackburn 1999, 188.

[42] See, among others, Borghetti 2015; Borghetti 2008, especially 208–214.

[43] “[…] lesquelz, ensamble unis, estoffoyent une très bonne chapelle dont il fut grandement honouré et prisiet des princes d’Alemaigne.” (Molinet 1935–1937, vol. 1, 470).

[44] Edition in Maas 1996, 43–47.

[45] In the text sections, first, forgiveness is requested from the Lord and thanks are given to the almighty King. Then, a prayer is made for “our (worldly) King” (“Pro rege nostro”) that the Lord may preserve him and that he may not fall into the hands of the enemies, and that the souls of the faithful may rest in peace. After a spoken “Our Father,” a final prayer to the Virgin Mary is sung, who carried the Son of the eternal Father. The musical petitions to God, for the king, and for Mary are concluded with a four-part “Amen” in each case. The music follows the rhythmic structure (in both the two- and four-part sections) exactly as per the text declamation (see Edwards 2011, 62 f.), and the largely homorhythmic, simple setting does not change throughout the piece, remaining the same for all three thematic areas.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Birgit Lodes: “„Mehrfacher Sinn“: Jacob Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens und die Königskrönung Maximilians”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/mehrfacher-sinn-jacob-obrechts-missa-salve-diva-parens-und-die-konigskronung-maximilians> (2017).