Musical Tributes for Maximilian I

On the Musical Sources of Maximilian's Court Chapel

Emperor Maximilian I pursued extensive cultural projects throughout his life. In doing so, he portrayed himself – among other things – as a lover and patron of music, for example in the Weisskunig (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33) or through the depiction of various wagons in the Triumphzug (Triumphal Procession), which representatively display his different musical ensembles (» I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I). He maintained a court chapel with highly trained singers and instrumentalists who regularly had to accompany him on his travels.[1] He also endowed foundations and scholarships for the performance of polyphonic Masses (with and without organ), for instance in Bruges and in Hall in Tyrol (» D. Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens, » D. SL Waldauf-Stiftung).

Although so many sources attest to the rich musical life at Maximilian’s court, almost no musical sources have survived from this context. We have some indirect evidence that members of Maximilian’s chapel acted as music scribes, and this skill was evidently passed down from older to younger singers. Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl) claimed that he alone, as a scribe (“Notist”), had written “sixteen volumes of vocal music” (“sechzechen gesang Buecher”),[2] and there must have been many more. Yet all the music manuscripts produced for Maximilian’s chapel have vanished. They have not – contrary to what Martin Bente argued in his 1968 dissertation[3] – survived in the holdings of the Bavarian State Library.[4]

To gain an impression of the liturgical and sacred music repertoire of Maximilian’s court chapel, one must rely on sources that are, in all likelihood, only indirectly connected to the court. This is often because it has been shown that they were created as copies of courtly sources. During the process of copying, compositions were sometimes adapted or modernised. According to current research, the following sources transmit music closely linked to the repertoire of Maximilian’s chapel: the choir book of the Innsbruck schoolmaster Nicolaus Leopold, in which various scribes recorded repertoire from the Innsbruck court chapel or the parish church (now cathedral) of St. James, Innsbruck, over several decades (» D-Mbs Mus. Hs. 3154);[5] the ‘Augsburg Songbook’ (» D-As Cod. 2° 142a), which, like the ‘Leopold Codex’, contains both secular and sacred compositions;[6] the practical manuscripts among the ‘Jena Choir Books’ (» D-Ju Ms. 30–33 and » D-WRhk Hs. A), some of which were copied for use by the court chapel of Elector Frederick the Wise, from sources related to Maximilian’s chapel;[7] a choirbook compiled from various fascicles written between c. 1500–1508 (» D-Sl Cod.Mus.Fol.I 47) that contains 10 Mass compositions, 1 Agnus, 1 Te Deum and 2 motets;[8] a manuscript compiled around 1520 in various fascicles, known as the ‘Pernner Codex’ (» D-Rp C 120);[9] numerous Munich choirbooks; through the mediation of Ludwig Senfl, containing many compositions by Henricus Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) (e.g., » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 31 with the » Abb. Introitus Resurrexi; D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–39; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 53; » G. Ludwig Senfl);[10] the representative printed motet book Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg 1520; » Abb. Liber selectarum cantionum) and the famous posthumous edition of Isaac’s settings of the Proper of the Mass in three volumes, » Choralis Constantinus (» G. Henricus Isaac, Kap. Isaac als Hofkomponist Maximilians I.). Of course, for all these (and many other potential) sources, research must always plausibly demonstrate the nature of their connection to Maximilian’s court – something that can be more or less conclusive depending on the case. Thus, the question of musical sources for the repertoire performed at Maximilian’s court forms a complex puzzle – and many pieces are certainly lost forever.

Two further sources have a strong connection to Maximilian’s chapel. One is a printed edition dedicated to Maximilian and his grandson Charles (» D. Musik für Kaiser Karl V.), which contains two motets explicitly tailored to Maximilian (» Ch. Printed Polyphonic Praise of the Ruler and the Virgin Mary). The other is a musical manuscript (» A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495; see Kap. Ein Geschenk für den frischgebackenen Kaiser: Das Alamire-Chorbuch A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 and Kap. Zum Repertoire der Handschrift A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495) from the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript complex, which reached Maximilian during his lifetime. Traces of use suggest that it was intensively used.

A Gift for the Newly Crowned Emperor: The Alamire Choirbook A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495

The magnificent choirbook A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 belongs to a group of more than sixty surviving choirbooks and sets of partbooks that are known in current scholarship as the ‘Burgundian-Habsburg music manuscripts.[11] These manuscripts were produced in a highly professional scriptorium located near the Burgundian-Habsburg courts of Archduke Philip the Handsome, Archduchess Margaret of Austria, and Archduke Charles (later Emperor Charles V) in Brussels and Mechelen. Created between approximately 1495 and 1534 – initially on parchment, the highest-quality material – these music manuscripts are often richly illuminated and served, among other purposes, as valuable gifts within Habsburg circles. The deluxe manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 is the first choirbook from this scriptorium to be produced under the direction of the professional copyist, singer, and diplomat Petrus Alamire.

» Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens shows the richly illuminated opening pages of the choir book, which comprises a total of 105 folios (210 pages). The miniatures depict the following: (top left) the Nativity scene (Christmas); (top right) Emperor Maximilian in prayer, with his guardian angel behind him; (bottom left) the coat of arms of Emperor Maximilian; (bottom right) the marital coat of arms of Maximilian and his wife Bianca Maria Sforza. Based on the heraldry, the manuscript can be dated to between spring 1508 (Maximilian’s proclamation as emperor elect) and December 1510 (the death of his wife). See » D. Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens.[12]

The musical notation – typical for the time – is written voice by voice in separate reading fields, not in score format. Top left: Discantus, the highest voice; bottom left: Tenor (note the text “Salve diva parens” instead of “Kyrie eleison”); top right: Altus (here labelled as ‘Contra’[tenor altus]), bottom right: Bassus. This layout is called ‘choirbook format’. A large ensemble (choir) could perform the different parts from this single book (» Abb. Kaiser Maximilians Kapelle). Iconographical representations show that it was also possible for instruments to double individual vocal lines (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei).

On the Repertoire of the Manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495

With the exception of the first composition, Jacob Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens (» D. Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens), all the Masses recorded in the Viennese deluxe choirbook A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 are highly modern works, created by contemporary composers who were (in a narrower or broader sense) associated with the French court: Antoine Févin, Loyset Compère, Antoine Bruhier, Pierrequin Thérache, and the famous Josquin Desprez, who was still alive at the time and whose music was popular at the French court.[13] Compared to earlier manuscripts from the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript complex, the exceptionally strong presence of modern French repertoire represents a striking shift.

The reason for this shift in repertoire appears to lie in the political events of 1507/08: Maximilian had long been striving for the imperial crown, but the French and their allies, the Venetians, successfully blocked his efforts. As a result, Maximilian saw war as inevitable and launched a propaganda campaign against the French and Venetians at the 1507 Imperial Diet in Constance (» D. Isaac und Maximilians Zeremonien, Kap. Musik für den Konstanzer Reichstag 1507). These opponents ultimately prevented Maximilian’s journey to Rome and thus his legitimate coronation as emperor by stationing nearly 10,000 troops near Verona. However, on February 4, 1508, Bishop Matthäus Lang was able to proclaim Maximilian as emperor elect in a solemn ceremony in Trent Cathedral, thereby asserting his claim to the imperial crown. The Pope later confirmed his new imperial title.[14]

Shortly thereafter, in June 1508, the newly crowned Emperor Maximilian travelled to the Netherlands. There, his daughter, Archduchess Margaret, was preparing a major political turn: reconciliation with France. After weeks of negotiations in the autumn of 1508, an agreement was finally reached on December 10, resulting in the formation of the League of Cambrai, which was announced during a festive Mass in the local cathedral. Maximilian signed the treaties on December 26, 1508, and ratified the League at the Brussels court on February 5, 1509. Officially, the League was a pact against the Turks, but in reality, it was also a military alliance (with the stronger of the former enemies) against the Venetians. For both the French King Louis XII and Maximilian, this marked a radical reversal of previous alliance policies. The contemporary “French” repertoire of the manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 appears to reflect this fundamental political shift: The repertoire, apparently acquired during the negotiations with the French court and incorporated into the manuscript, reflects the new political and intellectual orientation that would decisively shape Europe for years to come. Beginning with A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495, this orientation would long remain reflected in the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript tradition.

Printed Polyphonic Praises of the Ruler and the Virgin Mary

During his visit to the Netherlands as the newly proclaimed emperor (» Ch. On the Repertoire of the Manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495), Maximilian also paid a splendid visit to the city of Antwerp in September 1508, ahead of negotiations with France. He first invoked the Holy Spirit for guidance, then turned to the Virgin Mary, seeking her protection for his actions with the motet Sub tuum presidium (“Under your protection and shelter…”), a polyphonic setting of an ancient Marian prayer that evidently held special significance for Maximilian (» J. Body and Soul). During this visit, his grandson Charles (» D. Musik für Kaiser Karl V.) was also named Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire.

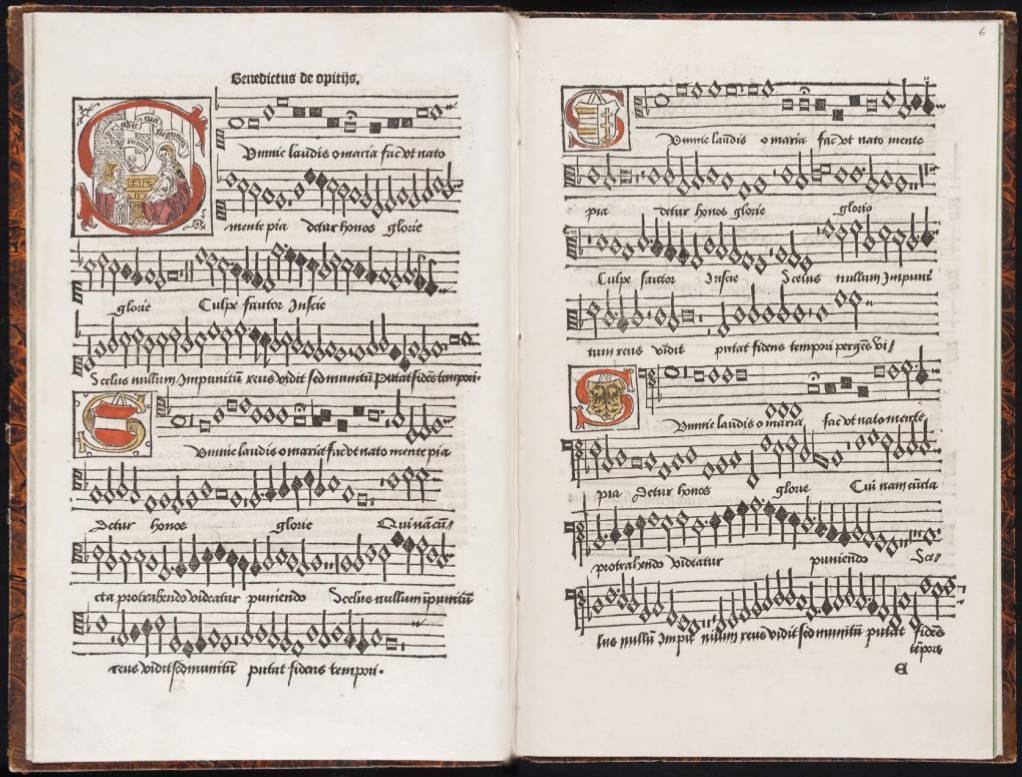

When, in February 1515, the accession of the fifteen-year-old Charles as Duke of Burgundy was staged in Antwerp, the city took the opportunity to commemorate and historicise the last major visit of Maximilian and Charles (that of 1508) in a media-savvy way. A forty-page printed work was produced titled: » Unio pro co[n]servatio[n]e rei publice / Lofzangen ter ere van Keizer Maximiliaan en zijn kleinzoon Karel den Vijfden (Union for the Preservation of the Commonwealth / Songs of Praise in Honor of Emperor Maximilian and His Grandson Charles V). This publication included praise of rulers, God, and the Virgin Mary in a wide variety of textual forms, images, and music:[15] laudatory poems, humanist letters, prayers, full-page woodcuts, and the two motets Sub tuum presidium and Summe laudis o Maria. This edition, issued by the Antwerp printer Jan de Gheet in 1515, is the earliest known print of polyphonic music from the Low Countries.[16] The 17 pages with notes – as in A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 in choirbook arrangement – and text are produced in block printing (woodcut) (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria).

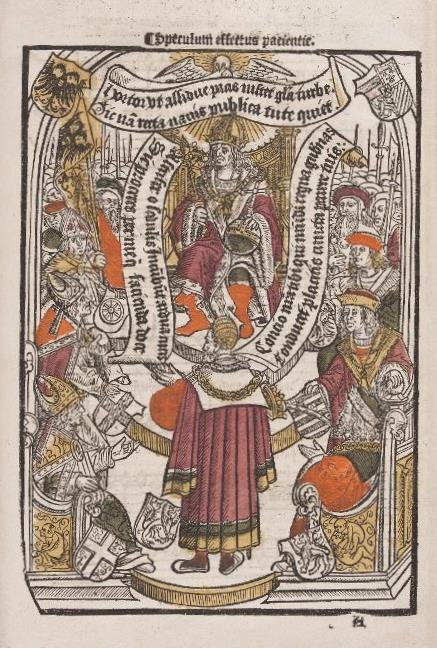

The printed work documents the events in Antwerp in 1508 and focuses on Maximilian’s achievements – his efforts for peace in the empire, unity among the princes, and the promotion of the common good[17]) – which he accomplished through the intercession and support of the Virgin Mary (see, for example, » Abb. Maximilian I. und Kurfürsten). The editions reflects a widely held concept of rulership at the time, vividly illustrated in the initial letter at the beginning of the Discantus part of the motet Summe laudis o Maria (Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Initial): Maximilian is depicted as ruler of the world, entrusted with his high office by God – just as many other rulers were. The Holy Spirit sends down its rays upon him, and Mary provides her indispensable support in the execution of his heavy responsibilities.

The centerpiece of the tribute print is the second motet, Summe laudis o Maria, whose text was written by Petrus de Opitiis, the brother of the composer of both motets, Benedictus de Opitiis (*c. 1476 – †1524).[18] The text of the motet is paraphrased and interpreted section by section in the print, and the motet is also introduced by a Latin poem that makes clear that the motet’s line of thought forms the conceptual foundation of the entire publication.

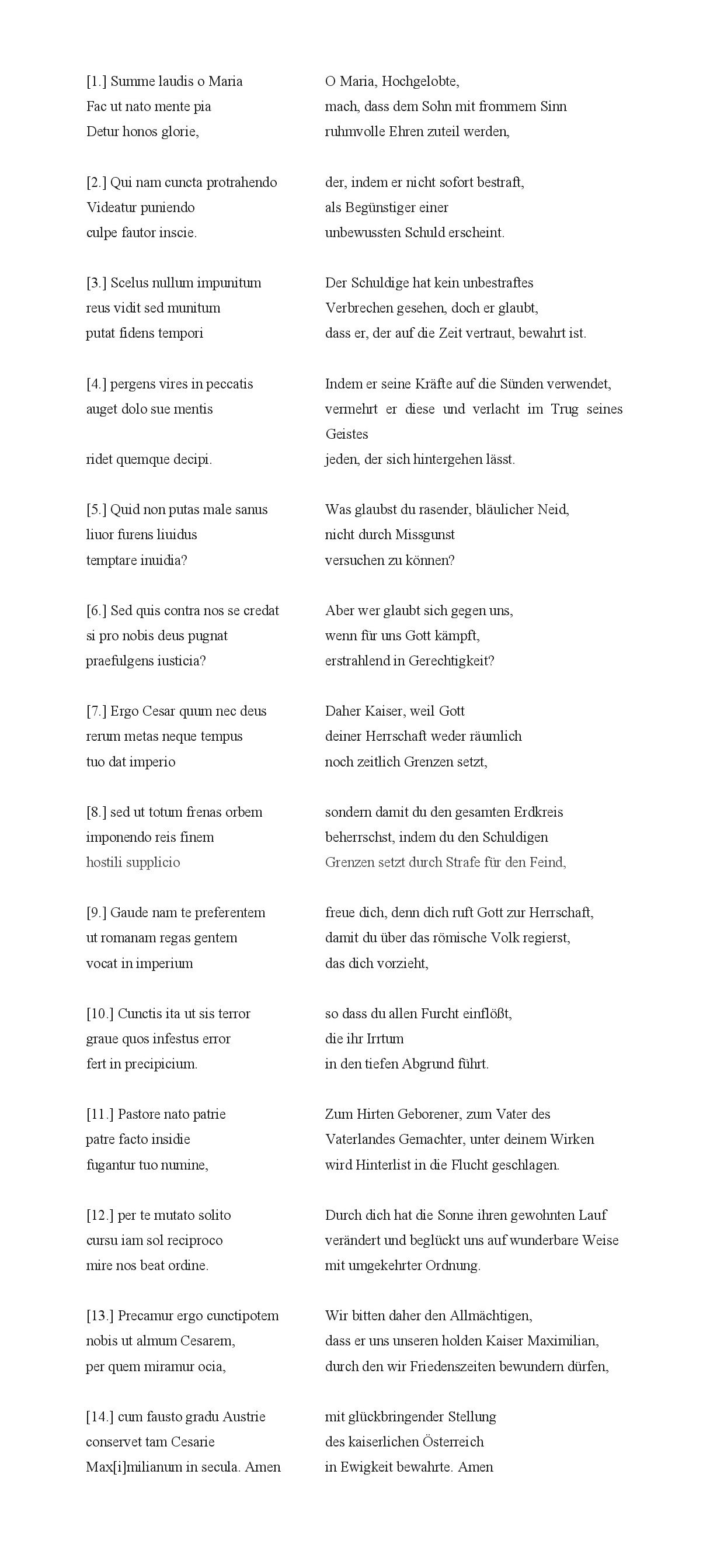

The text of Summe laudis (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Text) begins with a great praise of Mary, and then, through various expressions, addresses the legitimacy of Maximilian as emperor.[19] This was a significant theme in its historical context, since his rightful coronation in Rome had been prevented. The text culminates in an extended praise of the emperor.[20] The structure of the text – with the Marian praise first, followed by the praise of the ruler – thus mirrors that of Heinrich Isaac’s motet Virgo prudentissima (» D. Kap. Musik für den Konstanzer Reichstag 1507).

Visually, the intertwining of Marian devotion and political-secular themes in the Antwerp edition is emphasised by the initial of the motet Summe laudis, which shows Emperor Maximilian singing the words “We flee to you under your protection” (“Sub tuum presidium ad te confugimus”, > Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, » Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Initiale), thereby placing himself under Mary’s protection. Remarkably, the text suggests that the ‘Son of Mary’ is not only Jesus (who is never mentioned by name), but also Maximilian himself, who is to be praised (» D. Ch. ‘Multiple Meanings’: Mary as the Mother of the Future Ruler).

In his four-voice motet, Benedictus de Opitiis followed the structure of the text and placed clear polyphonic cadences at the end of nearly every textual unit. As was typical for the motet genre at the time, he composed a strongly imitative four-voice texture, and he highlighted certain passages through homorhythmic voice-leading to enhance textual clarity. Examples include the resonant opening section (“Summe laudis o Maria […] glorie”), the encouragement to fight with trust in God (sixth textual section), and the final two sections (13 and 14), where musical punctuation after the words “cunctipotem” and “Maximilianum” emphasises the pleas that God Almighty may preserve the peace-bringing Emperor Maximilian and the Austrian empire for eternity.

[1] See most recently Gasch 2015, especially 362–371.

[2] Supplication to King Ferdinand I in the year 1530; A-Whh Finance and Court Chamber Archive, Lower Austrian Chamber, Red No. 7. Printed in Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 3, 248.

[5] Strohm 1993, 519–522; edition in 4 volumes: Noblitt 1987–1996. See » K. The codex of Magister Nicolaus Leopold.

[6] On the secular sources (“songbooks”) associated with Maximilian’s court, see » B. Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst unter Maximilian I. and » B. Kap. Liederdrucke.

[7] See Heidrich 1993.

[8] Lodes 2019.

[9] Birkendorf 1994. The compositions are often recorded without text.

[11] See, among others, Kellman 1999; Bouckaert/Schreurs 2003; Saunders 2010; Burn 2015.

[12] Lodes 2009, 248.

[13] Missa Faisantz regretz and Missa Une mousse de Biscaye – the latter, although transmitted under Josquin’s name, was probably not composed by him.

[14] For the historical-political context, see, among others, Wiesflecker 1971–1986, Vol. 4, 1–27.

[15] The edition was produced in two editions (one with a Dutch summary, the other with a Latin summary) and is available as a facsimile with commentary: Nijhoff 1925, with a transcription of the two motets by Charles Van den Borren as an appendix. See also Schreurs 2001 and Wouters/Schreurs 1995. For a complete digital version of the Latin edition, see: http://depot.lias.be/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE4756261.

[16] A musical edition with the imperial coat of arms and that of the Margraviate of Antwerp had already been produced earlier in Antwerp: » Principium et ars tocius musice, Antwerpen: Jost de Negker (c. 1500–1508). However, this is a depiction of the Guidonian Hand with mensural notation and commentary, not a polyphonic composition. See Schreurs/Van der Stock 1997; a facsimile is also found on 173.

[17] Schlegelmilch 2011, especially 443–447.

[18] Benedictus held the position of organist at the Church of Our Lady in Antwerp from 1512 to 1516 and later moved to the English royal court. Only these two compositions by him are known.

[19] Victoria Panagl particularly highlights the lines “Ergo Cesar quum nec deus / rerum metas neque tempus / tuo dat imperio” (7th stanza; “Therefore, Caesar, since God sets neither spatial nor temporal limits to your rule”), which, as a Virgilian quotation, strongly emphasise Maximilian’s claim to power (as successor to the Roman Empire): In the Aeneid (1.278: “his ego non metas rerum nec tempora pono”), Jupiter speaks these words, looking ahead to the glorious rulers of the Roman Empire (see Panagl 2004, especially 73–81, here 78).

[20] See Dunning 1970, 61–64.

Recommended form of citation:

Birgit Lodes: „Musical Tributes for Maximilian I“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musical-tributes-for-maximilian-i> (2017).