Henricus Isaac’s Amazonas

“Every form of the art”

“I have received a book […] by our favourite Henricus Isaac […] whose compositions have always given me wondrous pleasure […] In that volume I was able to take pleasure in every form of the art. How capable Henricus is in each one anybody with even an elementary knowledge can easily perceive.” Thus wrote the Venetian ambassador Girolamo Donato to Lorenzo de’Medici in 1491, in thanks for the gift of a book of Isaac’s music.[1] The ambassador’s book is unfortunately lost, but Isaac’s surviving music in other sources overwhelmingly confirms the ambassador’s observation on his musical mastery: the dazzling variety of styles and forms, and the sheer quantity of Isaac’s works that has come down to us, are unparalleled by any other composer of his generation. He mastered the art-music of his own and the preceding generation in the way a great river unites its tributary waters and carries them forward. On the basis of such talent and experience, Isaac built a glittering international career supported by the most prestigious patrons of his day, including the Medici in Florence and the Habsburg court. He was appreciated as one of the most outstanding composers of his time, second only to Josquin Desprez in reputation. His service to the chapel of Emperor Maximilian I was honoured by the inclusion of his portrait in Maximilian’s famous Triumphzug.(» Abb. Isaac und Nicodemus).

Three early motets

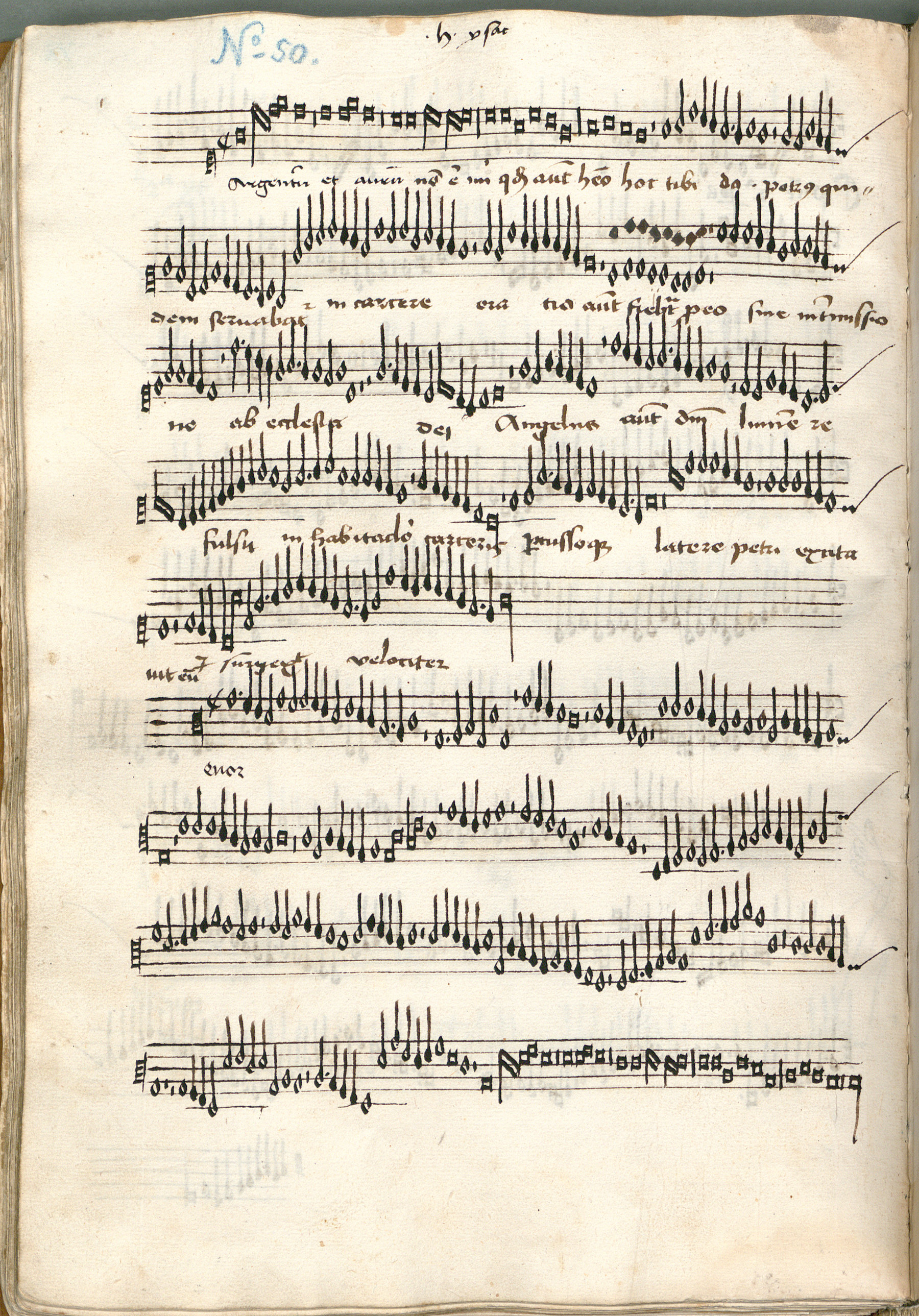

Isaac is first documented, already as an adult, in a casual payment from September 1484, at the Innsbruck court of Duke Sigismund of Tyrol.[2] Whether he was just passing through on the way from his native Low Countries to his first permanent appointment in Italy or whether he had had longer-term central-European connections is not clear. It is possible that his visit had something to do with the sumptuous wedding of Archduke Sigismund in February 1484: Isaac’s paymaster in September was the main organiser of the wedding ceremonies, court councillor and humanist Johannes Fuchsmagen (» I. Humanisten). The oldest source for any of Isaac’s music dates from around the same time, and probably comes from the same place: the so-called Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154), a large composite manuscript assembled between the mid-1460s and c. 1511 (» F. Geistliche Mehrstimmigkeit), which contains three of Isaac’s motets in a layer probably written in Innsbruck in the early 1480s (» Abb. Argentum et aurum).[3] The motets show intimate familiarity with central European musical styles. All three are based on plainchant melodies, and all are distinct in presenting their chant models multiple times.[4]

Argentum et aurum sets an antiphon for St. Peter and Paul in long, equal notes, first in the top voice, then in the bass, then in the tenor (» Abb. Argentum et aurum; » Hörbsp. ♫ Argentum et aurum). Ecce sacerdos magnus, setting an antiphon for a confessor bishop, presents its base melody twice between voice pairs in strict imitation, and finally spread phrase by phrase between all four voices. The final motet, setting the Marian sequence Inviolata, integra, et casta es Maria, is more ambitious, in five voices, and with two of the inner parts presenting the chant melody in canon. Unfortunately no surviving source preserves the second contratenor voice. However, analysis allows the missing voice to be reconstructed with relative security.[5]

From the Battle of Sarzanello to Marian prayer

In 1485 Isaac took up his first known permanent appointment, as a singer at the Baptistry of San Giovanni in Florence.[6] Alongside his sacred duties, he threw himself into other aspects of his new home-city’s musical life.

In the fifteenth century, as now, Carnival season, immediately before Lent, was an especially important moment in the annual calendar. Processions took place, songs were sung in the streets, and music-theatrical events organised. For the 1488 Florence Carnival season, Isaac composed a work on an unprecedented scale celebrating the recent military capture of the fortress of Sarzanello from the Genoese. The piece, A la battaglia, sets a long text in three strophes by Gentile Becchi, bishop of Arezzo and former teacher of Lorenzo de’Medici (» Hörbsp. ♫ A la battaglia).[7] A complete performance, with musical repeats for each strophe, would have lasted about a quarter of an hour. A remarkable series of letters written by an eye-witness tells us that, after a spectacular build-up and secret rehearsals, the work was met with bewilderment by the Florentine public.[8]

The failure may have had more to do with Becchi’s extravagant and slightly ridiculous text than the music. Separated from its original words, Isaac’s battle piece (Battaglia), with its attractive melodies, lively rhythms, and varied textures, was clearly thought worth preserving: sometime in the last decade of the fifteenth century or early in the sixteenth, it entered a German source, the Apel Codex (» D-LEu Ms. 1494), where it was shortened, and retexted with Latin, sacred words in honour of Mary, O praeclarissima atque gloriosa domina totius spirtitualis vitae.[9] A similar process can be seen in the manuscript » PL-Wu Ms. 2016 (c. 1500, Silesia), where the piece was given the text Ave sanctissima civitas divinitatis aeterno, and in the Fridolin Sicher Organ Tablature (CH-SGs Ms. Sang. 530, early sixteenth century, Constance/St. Gallen), where it has the title O dulcedo virginalis.[10]

A model, a mass, and a motet

Like all of his contemporaries, Isaac often based pieces on pre-existent music. The pre-existent material could be sacred or secular, high-class or low, one’s own, by a colleague, or distinguished predecessor. Its use could show off a composer’s talent, pay homage, and add extra layers of meaning. All of these are evident in two works – a motet and a mass cycle setting the five standard mass ordinary texts – that Isaac composed on Comme femme desconfortée, a song probably by the distinguished Burgundian court musician Gilles de Binche dit Binchois (c. 1400–1460; » Hörbsp. ♫ Comme femme).[11] Isaac probably composed both works in Florence in the early 1490s.

Isaac was one of a number of composers, including Josquin, in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth century to incorporate Comme femme into a sacred context.[12] Binchois’s song speaks, unusually, from a female viewpoint, and expresses the singer’s desire to die. In sacred contexts, the originally secular woman was transformed into the Virgin Mary. Isaac used the song’s tenor voice as the backbone for an imposing motet for six voices, Angeli archangeli. Against Binchois’s tenor, the other five voices draw on texts from the liturgy of All Saints. The whole was probably intended to symbolize the Assumption, when Mary was joined by the saints and crowned Queen of Heaven. Isaac used Comme femme again, in a mass cycle of the same title. Here the presence of Binchois’s song (usually paraphrased in the tenor) in each of the movements marks the otherwise neutral ordinary texts as appropriate for Marian feasts.[13]

“I […] will use all my art for his Majesty’s chapel”

The 1490s saw the most dramatic turn-about conceivable in the Florentine musical scene: Lorenzo il Magnifico’s many years of stable patronage ended with his death in 1492, and by 1494 the Dominican friar Girolamo Savanarola had instituted a religious law under which elaborate liturgical music had no place.[14] Isaac not only lost his job as a singer at the Baptistry of San Giovanni, but found himself in an environment in which his very craft as a producer of musical art-works was viewed with suspicion. It was clear that he would have to leave Florence until a more tolerant regime returned.

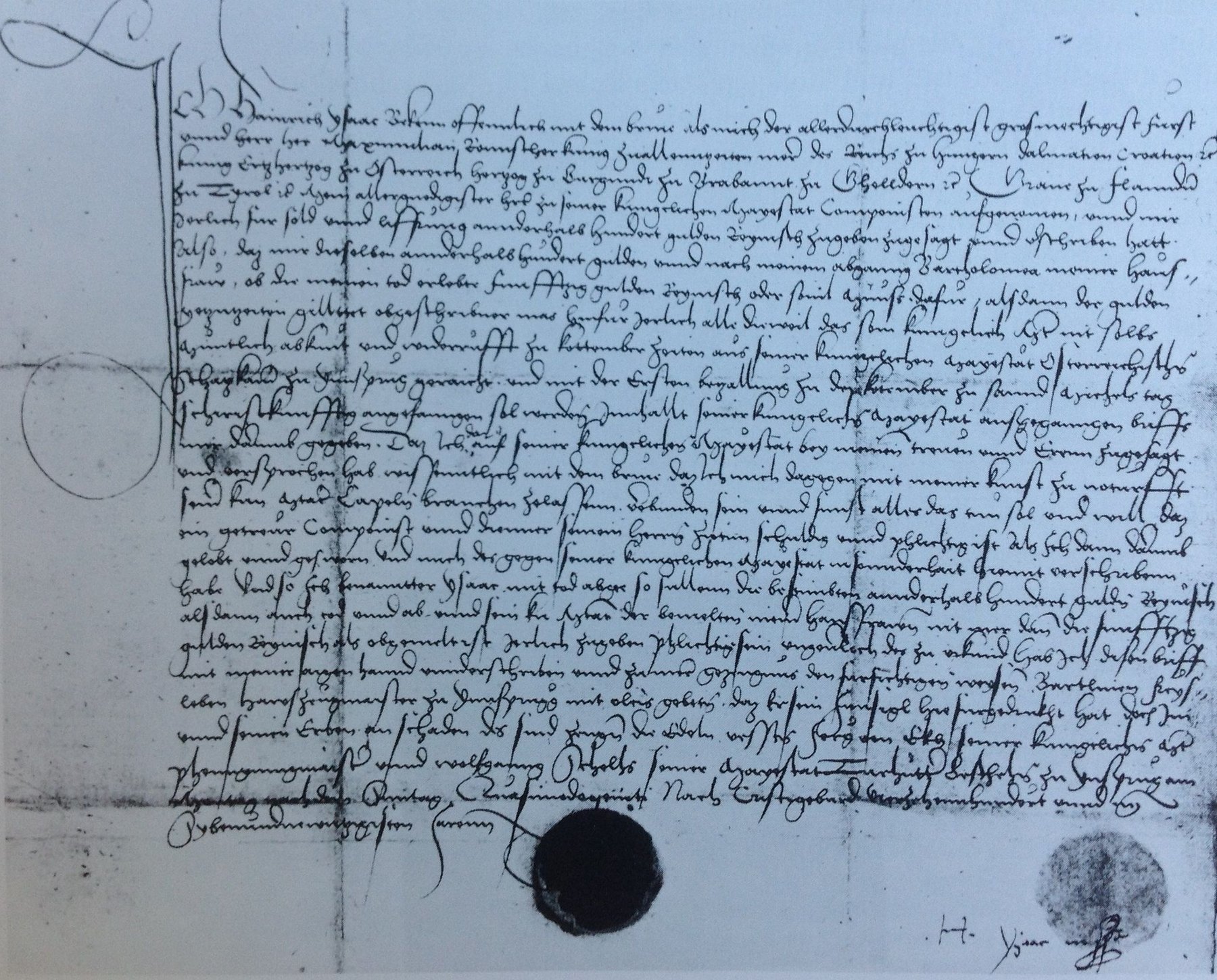

A composer with Isaac’s credentials would not remain unemployed for long. In 1496 he took up a position at the Imperial court of Maximilian I, and left Florence for Vienna. With Isaac’s appointment, Maximilian hoped to elevate his court’s musical standards to a level unrivalled anywhere in Europe. To achieve this, Maximilian took Isaac into his service not as a singer, but as componist—court composer—and, in so doing, Isaac became the first musician known to have been employed exclusively to produce musical works.[15] Maximilian promised Isaac a reasonable salary and a pension for his wife, should she outlive him, and in return, Isaac promised to “use all his art” for Maximilian’s chapel, and to serve as a “true composer” (» Abb. Isaac’s contract).[16]

“Hic maxime Ecclesiasticum ornavit cantum”

What was expected of a “true composer”? Isaac’s contract with Maximilian makes it clear that the emperor wanted music for his chapel, where he hoped to draw together outstanding musical specialists with various skills. Although the contract gives no details about particular genres or works to be composed, insight can be gained by looking at the sacred music that Isaac produced once he entered Maximilian’s service. In particular, he cultivated to an unprecedented degree two regionally specific musical forms almost entirely absent in his earlier work and in the outputs of his contemporaries: the chant-based alternation (alternatim) mass ordinary cycle, and the polyphonic mass proper cycle.

The alternatim ordinary cycle takes the relevant plainchant as its basis in each movement: the Kyrie takes a Kyrie chant, the Gloria a Gloria chant, and so forth. This practice harks back to the earliest polyphonic mass ordinary settings, but had been overshadowed, from the early fifteenth century onwards, by cyclic techniques in which the same borrowed material was cited in each movement. Isaac composed twenty-one alternatim cycles, systematically exploring scorings from three to six voices, and festal types from the most everyday, to the most important, including Easter and solemn and Marian feasts. Sections treating parts of the plainchant in polyphony are typically relatively short, and alternate with either improvised organ music or monophonic chant.[17]

The mass proper refers to those parts of the mass with texts and melodies that change from feast to feast. The practice of setting these in polyphony is traceable to the earliest surviving sources for polyphony of any kind: the first major repertory of practical polyphony, contained in the so-called Winchester Troper (c. 1020–30), consists largely of such settings;[18] so too does the first polyphonic repertory with fixed rhythm, associated with Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.[19] After these spectacular early witnesses, however, the further development of the genre is difficult to trace as it is only poorly represented in sources from the subsequent two centuries. Substantial collections of polyphonic propers appear again from the mid-fifteenth century, the most important ones being connected in some way to the imperial court.[20] These sources suggest that the court regularly sang the introit and sequence polyphonically by the time of Isaac’s appointment, and form the backdrop to his monumental and unparalleled contribution to the genre.

Some 400 of Isaac’s mass proper settings survive, grouped into cycles for feasts throughout the year.[21] Isaac set the introit, alleluia, sequence (if appropriate), and communion. As with the alternatim ordinaries, the settings are based on the relevant plainchant melodies (» Hörbsp. ♫ Puer natus est nobis, Isaac).[22] Isaac’s overwhelming cultivation of the genre in service of the Habsburg chapel inspired envy and long-lasting admiration: early in the production of the imperial series, the court of Elector Friedrich the Wise copied a significant number of the cycles;[23] and in 1507–1508, the cathedral at Konstanz succeeded in recruiting Isaac himself to compose a series of mass propers for high feasts for them.

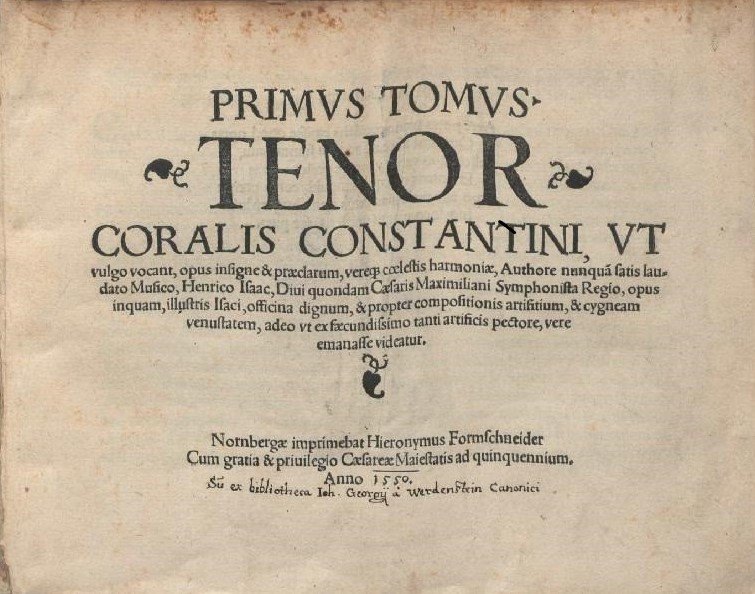

Maximilian clearly sought to monumentalize the liturgy of his chapel with appropriate, chant-based polyphonic music for every occasion. Isaac’s alternatim ordinaries and mass propers were as striking to his contemporaries as they still are to us in this respect. In his summary of Isaac’s achievements, Heinrich Glarean, one of the most important music theorists of the sixteenth century, concluded that, “He embellished plainchant especially; namely he had seen a majesty and natural strength in it which surpasses by far the themes invented in our time.” [24] The status of Isaac’s chant-based music can be judged from the publication, in the mid-sixteenth century, of a three-volume collected edition of his mass propers, under the title » Coralis constantinus (vol. 1: 1550; vols. 2 and 3: 1555; » Abb. Title page Coralis constantinus).[25] At the time, such a single-author edition, produced so long after a composer’s death, was unprecedented. Not even Josquin received such lavish posthumous attention. The print provided a core mass proper repertory for numerous institutions throughout the second half of the sixteenth century.[26]

“Ysaac de manu sua”

A manuscript now in the Deutsche Staatsbibliothek in Berlin (» D-B Mus. ms. 40021) contains three pieces by Isaac that are indicated as in his own hand – “de manu sua”. The three pieces are a setting of a sequence, Sanctissimae virginis, the pilgrim song In Gottes Namen, and the mass Una musque de Biscaye. The mass is actually not in Isaac’s hand, but the remaining two count as the first securely identifiable composer autographs in Western music history.[27] The pages with these compositions on have fold-marks that show that they were sent as letters, and eventually bound into the Berlin manuscript as additions at the start and end of the book. The paper on which they were written dates from c. 1500.[28]

In Gottes Namen, a four-voice setting of the well-known medieval Leise (» B. Geistliches Lied; » J. SL In Gottes namen faren wir), is cleanly written: Isaac had clearly composed the work prior to making this copy, then simply transferred the finished piece to the page that was sent as a letter (Link: » Abb. Isaac In gottes namen). The copy of the four-voice Sanctissimae virginis, setting a plainchant sequence, is different: it was made earlier in the compositional process than In Gottes Namen, and contains revisions and corrections that give insight into Isaac’s compositional methods ( Link: » Abb. Sanctissimae virginis.[29] The layout and alterations suggest he worked phrase by phrase, and polished his initial work while transferring it to paper. The final section of the piece appears in two different versions, with the same top part, but different lower ones.

Turkish dervish-music and European counterpoint

The traumatic effect of the fall of Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Empire, to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 is hard to overestimate. Turkophobia gripped European consciousness for centuries afterwards, crusades were regularly planned, and masses “against the Turks” (“contra turcos”) entered the liturgy with 300-year indulgences for those who celebrated them.[30] Guillaume Du Fay composed four laments on the fall shortly after the event (unfortunately only one now survives), [31] and the long tradition, stretching from the mid-fifteenth through the sixteenth century, of composing mass ordinary settings on the song L’homme armé may owe something to the situation. However, one of the most remarkable musical results of the West’s encounters with the Ottomans is Isaac’s piece usually known as La la hö hö, but called Allahoy in its earliest source.[32] The piece is based around obsessive repetitions of a short motif of two pitches, a step apart, both of which are repeated a number of times. The motif is almost continually present, and transposed to begin on an unusually wide variety of starting-notes (» Notenbsp. La la hö hö). These mark the piece out as curious, if not entirely without parallel.[33] (» Hörbsp. ♫ La la hö hö) What is truly extraordinary is the identification of the motif that inspired the work as a formula recited by Turkish dervishes (“Lā ilāha illa’llāh” – “no God other than Allah”).[34] No other composer in Isaac’s time is known to have been inspired by non-Western musical material.

How and where might Isaac have heard such a formula? The transmission of the piece exclusively in central-European sources suggests that he composed it during his time in the service of Emperor Maximilian I. The Emperor was obsessed with a crusade against the Turks, but this went (only superficially paradoxically) hand in hand with increased diplomatic contacts.[35] Isaac may have heard the formula during such a diplomatic encounter: the first, and most spectacular of these took place in Innsbruck in summer 1497, only shortly after he had entered imperial service. Maximilian welcomed (at Innsbruck) a Turkish embassy that stayed for several months, surrounded by extraordinary local excitement and interest.[36] It is equally possible that Isaac was told about Ottoman music-making by returning ambassadors that Maximilian regularly sent to Constantinople.

A solution to the origin of La la hö hö’s musical material surrounds the work in new mysteries. No surviving source has more than a text incipit, but does that mean that the piece was conceived for instruments rather than voices? The dervish formula is vocal, but if Isaac’s piece did have a text, what form may that have taken? Why did Isaac compose it at all? Purely personal interest seems unlikely, but what was its original context? Theatrical-dramatic? Honorific? Was the piece meant respectfully – perhaps even as a gift to Turkish diplomats – or mockingly? Only hypotheses can be offered in answers to these questions. The story of La la hö hö has an appropriately unexpected postscript: the piece was Christianized – perhaps unwittingly by a composer unaware of its origins – through use as the basis for a mass setting, the Missa Lalahe.

Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen

Among Isaac’s most significant contributions to music in German-speaking lands was his cultivation of German song. Alongside setting earthy, even downright obscene, texts, he played a particularly important role in the development of courtly styles. One song of the latter kind, Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen, is undoubtedly his best-known work, and one with a long and rich reception-history that has shrouded it in some myth and mystery. That Emperor Maximilian wrote the words can be dismissed, though whether the text originally began with a word other than “Innsbruck” is uncertain.[37] Whether Isaac actually composed the tune or simply arranged it is also still debated.[38] The tune’s rhythmic and melodic features, at least, are typical of the late fifteenth century and do not suggest that it was at all ancient then.[39]

Uncertainty over the origins of the song are caused in part by the first surviving source, Georg Forster’s music print » Ein Ausszug guter alter und newer Teutscher Liedlein, dating from 1539, twenty-two years after Isaac’s death.[40] Forster’s edition helped assure the song’s popularity for the rest of the sixteenth century. Much evidence testifies to the song’s popularity. Arrangements survive for lute and organ, the song was reworked by other composers (including Christian Hollander and Jobst von Brandt), and, most importantly, the melody was repeatedly contrafacted.[41] Especially significant in this respect was its mid-sixteenth century adoption into the Lutheran chorale repertory with the sacred text O Welt ich muss dich lassen. In the seventeenth century, the song received a second sacred text, Nun ruhen alle Wälder, in which form it was included by Bach in his passions. The song’s original form was rediscovered in the nineteenth century and reattached to Isaac as Isaac himself was rediscovered and installed as a “German” composer of national(istic) significance.[42] Simultaneously, the melody was absorbed into “folk-music” collections, where it quickly gained an established place, culminating in the twentieth century in National Socialist appropriation as representative of the essence of the German people.[43]

The piece’s extraordinary popularity, and the fact that other sixteenth-century German songs are now relatively unknown, obscure the many ways in which this song is profoundly atypical of its repertory. The six-line poetic form of its strophes is not a familiar pattern, and the placing of the melody in the top voice, with simple harmonization beneath, is not a texture encountered in other German songs of the time. These characteristics recall Isaac’s Italian songs, and seem typical of his desire to fuse national styles. A mass ordinary setting that quotes various songs, the Missa Carminum, offers an alternative arrangement of the melody, in canon between tenor and altus. The mass was once attributed to Isaac, but his authorship has been questioned.[44]

“Isaac, das war der Name sein. Halt wohl, es werd vergessen nit”

Manuscript copies, printed editions, theoretical treatises, and performance traditions, among others, all played a role in perpetuating Isaac’s reputation and keeping his music alive after his death.[45] Behind such perpetuation lay the actions of people in direct contact with, and trained by, Isaac himself. His students may have included Adam Rener, Balthasar Resinarius, and Petrus Tritonius. Most importantly, they included Ludwig Senfl, the leading composer in German-speaking lands after Isaac.[46]

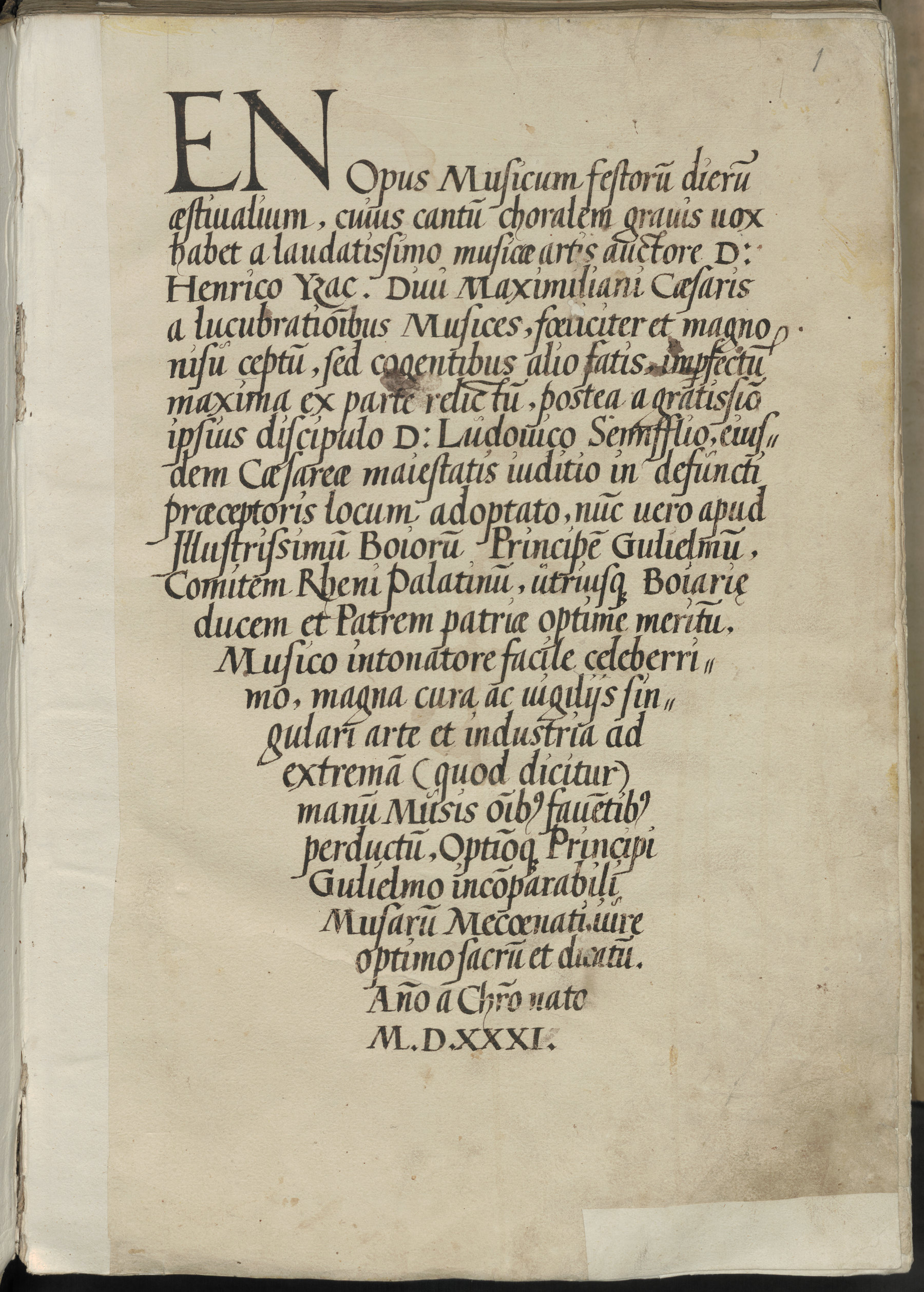

Senfl’s music, both secular and sacred, bears technical and structural traces of his master’s teaching.[47] Furthermore, under Senfl’s supervision, a monumental series of choirbooks were produced in the 1520s and 1530s without which a good deal of Isaac’s sacred music would not have survived.[48] Four of these books, assembled in 1531 and collectively called the Opus musicum manuscripts, present a touching insight into this master-pupil relationship: they contain a series of mass proper settings with the chant in the lowest voice that Isaac had left incomplete, assembled together alongside Senfl’s completions.[49] On the title page of two of the manuscripts Senfl describes himself as Isaac’s “most grateful pupil” (» Abb. Title page En Opus Musicum). In turn, Glarean paid Senfl a compliment that he would undoubtedly have cherished when he observed that the latter had “attained a distinguished name among composers, and one not at all unworthy of his master Heinrich Isaac”.[50] Isaac had become a benchmark by which to judge those that followed.

[1] Blackburn 1996, 21.

[2] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 19; Picker 1991, 4; Senn 1954, 10.

[3] More recent research confirms the date of c. 1476 originally proposed by Thomas Noblitt for the three motets, see » K. 7 The Codex of Nicolaus Leopold. » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154 is viewable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/; Isaac’s motets are on fol. 72v, fol. 73v, and fol. 74v. Modern edition: Noblitt 1987–1996. On dating, see Rifkin 2003, 294–307. On possible identities of the scribes, see Strohm 1993, 519 ff. (though doubted in Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103). See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[4] See, further, Strohm 1993, 526; Kempson 1998, esp. vol. 1, 29–35, 92–106; Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[5] Cumming 2011, with reconstructed score at 268–274.

[6] Relevant documents in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, after D’Accone 1961 and D’Accone 1963.

[7] Complete text given in McGee 1983.

[9] Modern edition of » D-LEu Ms. 1494: Gerber et al. 1956–1975.

[11] The authenticity of Comme femme has been disputed by some, but is accepted in Fallows 2001.

[13] See also Staehelin 1977, vol. 3, 81–86.

[15] Wegman 1996, esp. 461–469; Wegman 2011.

[16] Full document quoted in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 46 f.

[19] See further Burn/Gasch 2011; Strohm 2011.

[20] Especially the Trent Codices and the St. Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); Strohm 2011, 42 ff. and the literature cited there.

[21] It is difficult to specify how many feasts Isaac’s surviving mass propers could cover, given the multiple use of the common of saints, and the uncertaintly around the details of the liturgies for which Isaac composed. An estimate of around 150 days in the year seems reasonable.

[24] Glarean 1547, 460; trans. in Picker 1991, 17 f.

[25] It is generally agreed that the first and third volumes contain imperial music, and the second music for Konstanz; see Burn 2003. Rothenberg 2011a presents an alternative hypothesis.

[26] Among others, the monastery of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, and the monasteries of Neresheim and Ottobeuren; see especially Eichner 2011 and Rimek 2011.

[28] Digitised images of the manuscript, including the two autographs, are available at: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000. The “de manu sua” pieces are at fols. 8 ff., fol. 255v–256v, and fol. 294.

[29] Owens 1997, 258–290.

[30] The earliest mass “contra Turcos” is traceable to 1453/54; Jensen 2007, 117.

[31] The letter in which Du Fay mentions his laments is reproduced in Fallows 1982; Kirkman 2010, 121 f.

[32] Concordances to » D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (c. 1498–1500): D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 (Lalla hoe hoe; 1520s); » A-Wn Mus.Hs.18810 (La la hö hö; 1524–1533). D-B preserves the work in a longer form than the concordances, with a central section absent elsewhere. The longer form is most likely the original; transcriptions of the longer version in Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, and Just 1990/1991, vol. 3. For digitised images of D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 see: http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/view/cim/cim.html; for D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (the piece is at fol. 224v; piece No. 110): http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000.

[33] Somewhat similar is Isaac’s “motet on a fantasia called La mi la sol”, which he composed for a job-interview in Ferrara in 1502, though the basic material of La la hö hö is even more striking in its limitations, and not connected to the piece’s title through solmisation-syllables.

[35] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, passim.

[36] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 156; also Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, 38 n. 24.

[37] Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 255; Staehelin 1989 proposes that the original first word was not “Innsbruck” but “Zurück”.

[38] Strohm argues that he did in Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[39] Strohm 2014, 7.

[40] RISM 1539/27. This source is also now viewable online, at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00074418/images/?viewmode=1.

[41] Salmen 1997, 250.

[42] First in Ernst Ludwig Gerber’s Neues historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig 1812–1814); see Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 258.

[43] Drexel 1997, 285.

[45] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 89–130; Burn 2006.

[46] Strohm, in Strohm/Kempson 2001. On Isaac’s pupils, see Picker 1991, 15 f. On Senfl, see » G. Ludwig Senfl.

[48] Bente 1968; with important revisions in Lodes 2006. Most of the books are viewable at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[49] D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–38, all consultable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[50] Glarean 1547, 261; cited in Picker 1991, 15.

Heidrich 1993 | Hell 1985 | Rothenberg 2011b | Staehelin 2001

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

David Burn: „Henricus Isaac’s Amazonas“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/henricus-isaacs-amazonas> (2016).