“Hic maxime Ecclesiasticum ornavit cantum”

What was expected of a “true composer”? Isaac’s contract with Maximilian makes it clear that the emperor wanted music for his chapel, where he hoped to draw together outstanding musical specialists with various skills. Although the contract gives no details about particular genres or works to be composed, insight can be gained by looking at the sacred music that Isaac produced once he entered Maximilian’s service. In particular, he cultivated to an unprecedented degree two regionally specific musical forms almost entirely absent in his earlier work and in the outputs of his contemporaries: the chant-based alternation (alternatim) mass ordinary cycle, and the polyphonic mass proper cycle.

The alternatim ordinary cycle takes the relevant plainchant as its basis in each movement: the Kyrie takes a Kyrie chant, the Gloria a Gloria chant, and so forth. This practice harks back to the earliest polyphonic mass ordinary settings, but had been overshadowed, from the early fifteenth century onwards, by cyclic techniques in which the same borrowed material was cited in each movement. Isaac composed twenty-one alternatim cycles, systematically exploring scorings from three to six voices, and festal types from the most everyday, to the most important, including Easter and solemn and Marian feasts. Sections treating parts of the plainchant in polyphony are typically relatively short, and alternate with either improvised organ music or monophonic chant.[17]

The mass proper refers to those parts of the mass with texts and melodies that change from feast to feast. The practice of setting these in polyphony is traceable to the earliest surviving sources for polyphony of any kind: the first major repertory of practical polyphony, contained in the so-called Winchester Troper (c. 1020–30), consists largely of such settings;[18] so too does the first polyphonic repertory with fixed rhythm, associated with Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.[19] After these spectacular early witnesses, however, the further development of the genre is difficult to trace as it is only poorly represented in sources from the subsequent two centuries. Substantial collections of polyphonic propers appear again from the mid-fifteenth century, the most important ones being connected in some way to the imperial court.[20] These sources suggest that the court regularly sang the introit and sequence polyphonically by the time of Isaac’s appointment, and form the backdrop to his monumental and unparalleled contribution to the genre.

Some 400 of Isaac’s mass proper settings survive, grouped into cycles for feasts throughout the year.[21] Isaac set the introit, alleluia, sequence (if appropriate), and communion. As with the alternatim ordinaries, the settings are based on the relevant plainchant melodies (» Hörbsp. ♫ Puer natus est nobis, Isaac).[22] Isaac’s overwhelming cultivation of the genre in service of the Habsburg chapel inspired envy and long-lasting admiration: early in the production of the imperial series, the court of Elector Friedrich the Wise copied a significant number of the cycles;[23] and in 1507–1508, the cathedral at Konstanz succeeded in recruiting Isaac himself to compose a series of mass propers for high feasts for them.

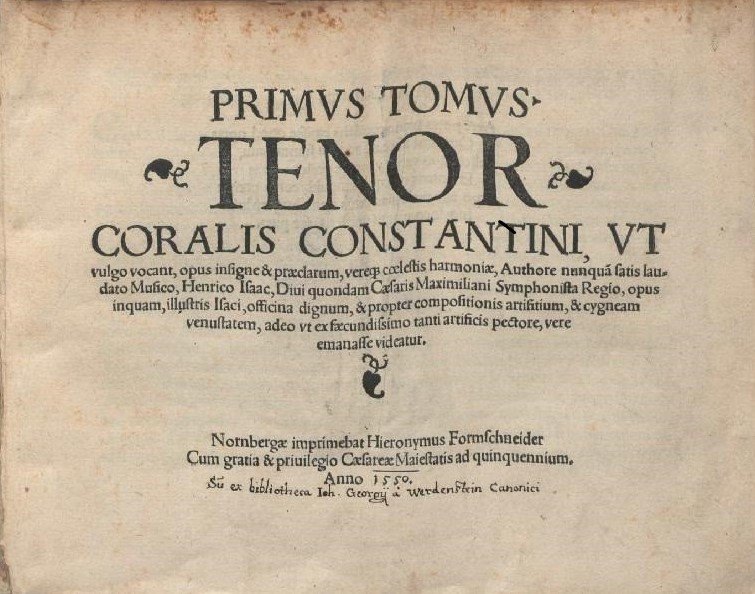

Maximilian clearly sought to monumentalize the liturgy of his chapel with appropriate, chant-based polyphonic music for every occasion. Isaac’s alternatim ordinaries and mass propers were as striking to his contemporaries as they still are to us in this respect. In his summary of Isaac’s achievements, Heinrich Glarean, one of the most important music theorists of the sixteenth century, concluded that, “He embellished plainchant especially; namely he had seen a majesty and natural strength in it which surpasses by far the themes invented in our time.” [24] The status of Isaac’s chant-based music can be judged from the publication, in the mid-sixteenth century, of a three-volume collected edition of his mass propers, under the title » Coralis constantinus (vol. 1: 1550; vols. 2 and 3: 1555; » Abb. Title page Coralis constantinus).[25] At the time, such a single-author edition, produced so long after a composer’s death, was unprecedented. Not even Josquin received such lavish posthumous attention. The print provided a core mass proper repertory for numerous institutions throughout the second half of the sixteenth century.[26]

[19] See further Burn/Gasch 2011; Strohm 2011.

[20] Especially the Trent Codices and the St. Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); Strohm 2011, 42 ff. and the literature cited there.

[21] It is difficult to specify how many feasts Isaac’s surviving mass propers could cover, given the multiple use of the common of saints, and the uncertaintly around the details of the liturgies for which Isaac composed. An estimate of around 150 days in the year seems reasonable.

[22] For an analysis of an introit, see Burn 2010.

[23] Discussed extensively in Burn 2002.

[24] Glarean 1547, 460; trans. in Picker 1991, 17 f.

[25] It is generally agreed that the first and third volumes contain imperial music, and the second music for Konstanz; see Burn 2003. Rothenberg 2011a presents an alternative hypothesis.

[26] Among others, the monastery of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, and the monasteries of Neresheim and Ottobeuren; see especially Eichner 2011 and Rimek 2011.

[1] Blackburn 1996, 21.

[2] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 19; Picker 1991, 4; Senn 1954, 10.

[3] More recent research confirms the date of c. 1476 originally proposed by Thomas Noblitt for the three motets, see » K. 7 The Codex of Nicolaus Leopold. » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154 is viewable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/; Isaac’s motets are on fol. 72v, fol. 73v, and fol. 74v. Modern edition: Noblitt 1987–1996. On dating, see Rifkin 2003, 294–307. On possible identities of the scribes, see Strohm 1993, 519 ff. (though doubted in Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103). See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[4] See, further, Strohm 1993, 526; Kempson 1998, esp. vol. 1, 29–35, 92–106; Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[5] Cumming 2011, with reconstructed score at 268–274.

[6] Relevant documents in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, after D’Accone 1961 and D’Accone 1963.

[7] Complete text given in McGee 1983.

[9] Modern edition of » D-LEu Ms. 1494: Gerber et al. 1956–1975.

[11] The authenticity of Comme femme has been disputed by some, but is accepted in Fallows 2001.

[13] See also Staehelin 1977, vol. 3, 81–86.

[15] Wegman 1996, esp. 461–469; Wegman 2011.

[16] Full document quoted in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 46 f.

[19] See further Burn/Gasch 2011; Strohm 2011.

[20] Especially the Trent Codices and the St. Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); Strohm 2011, 42 ff. and the literature cited there.

[21] It is difficult to specify how many feasts Isaac’s surviving mass propers could cover, given the multiple use of the common of saints, and the uncertaintly around the details of the liturgies for which Isaac composed. An estimate of around 150 days in the year seems reasonable.

[24] Glarean 1547, 460; trans. in Picker 1991, 17 f.

[25] It is generally agreed that the first and third volumes contain imperial music, and the second music for Konstanz; see Burn 2003. Rothenberg 2011a presents an alternative hypothesis.

[26] Among others, the monastery of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, and the monasteries of Neresheim and Ottobeuren; see especially Eichner 2011 and Rimek 2011.

[28] Digitised images of the manuscript, including the two autographs, are available at: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000. The “de manu sua” pieces are at fols. 8 ff., fol. 255v–256v, and fol. 294.

[29] Owens 1997, 258–290.

[30] The earliest mass “contra Turcos” is traceable to 1453/54; Jensen 2007, 117.

[31] The letter in which Du Fay mentions his laments is reproduced in Fallows 1982; Kirkman 2010, 121 f.

[32] Concordances to » D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (c. 1498–1500): D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 (Lalla hoe hoe; 1520s); » A-Wn Mus.Hs.18810 (La la hö hö; 1524–1533). D-B preserves the work in a longer form than the concordances, with a central section absent elsewhere. The longer form is most likely the original; transcriptions of the longer version in Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, and Just 1990/1991, vol. 3. For digitised images of D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 see: http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/view/cim/cim.html; for D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (the piece is at fol. 224v; piece No. 110): http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000.

[33] Somewhat similar is Isaac’s “motet on a fantasia called La mi la sol”, which he composed for a job-interview in Ferrara in 1502, though the basic material of La la hö hö is even more striking in its limitations, and not connected to the piece’s title through solmisation-syllables.

[35] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, passim.

[36] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 156; also Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, 38 n. 24.

[37] Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 255; Staehelin 1989 proposes that the original first word was not “Innsbruck” but “Zurück”.

[38] Strohm argues that he did in Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[39] Strohm 2014, 7.

[40] RISM 1539/27. This source is also now viewable online, at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00074418/images/?viewmode=1.

[41] Salmen 1997, 250.

[42] First in Ernst Ludwig Gerber’s Neues historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig 1812–1814); see Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 258.

[43] Drexel 1997, 285.

[45] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 89–130; Burn 2006.

[46] Strohm, in Strohm/Kempson 2001. On Isaac’s pupils, see Picker 1991, 15 f. On Senfl, see » G. Ludwig Senfl.

[48] Bente 1968; with important revisions in Lodes 2006. Most of the books are viewable at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[49] D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–38, all consultable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[50] Glarean 1547, 261; cited in Picker 1991, 15.