“Isaac, das war der Name sein. Halt wohl, es werd vergessen nit”

Manuscript copies, printed editions, theoretical treatises, and performance traditions, among others, all played a role in perpetuating Isaac’s reputation and keeping his music alive after his death.[45] Behind such perpetuation lay the actions of people in direct contact with, and trained by, Isaac himself. His students may have included Adam Rener, Balthasar Resinarius, and Petrus Tritonius. Most importantly, they included Ludwig Senfl, the leading composer in German-speaking lands after Isaac.[46]

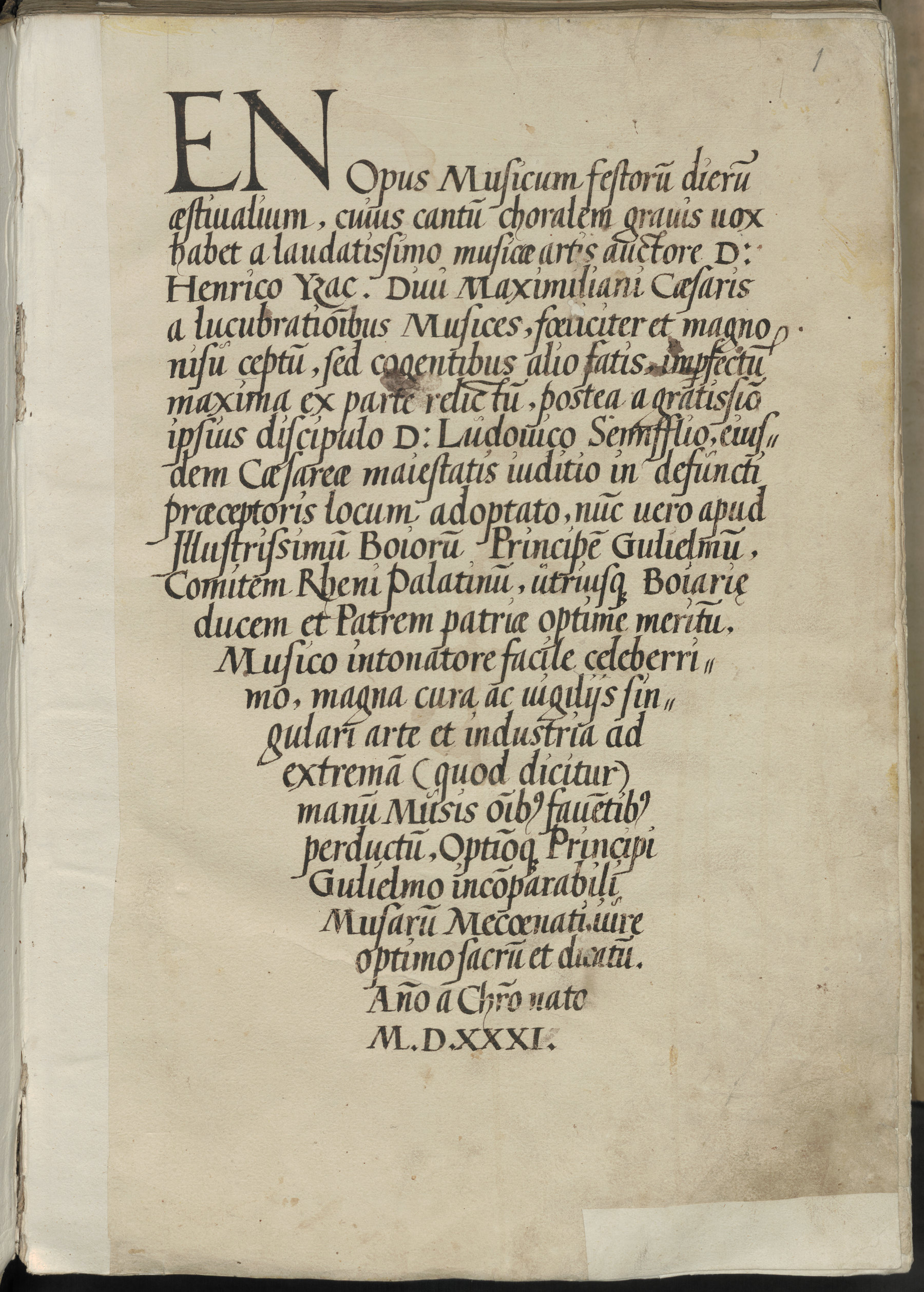

Senfl’s music, both secular and sacred, bears technical and structural traces of his master’s teaching.[47] Furthermore, under Senfl’s supervision, a monumental series of choirbooks were produced in the 1520s and 1530s without which a good deal of Isaac’s sacred music would not have survived.[48] Four of these books, assembled in 1531 and collectively called the Opus musicum manuscripts, present a touching insight into this master-pupil relationship: they contain a series of mass proper settings with the chant in the lowest voice that Isaac had left incomplete, assembled together alongside Senfl’s completions.[49] On the title page of two of the manuscripts Senfl describes himself as Isaac’s “most grateful pupil” (» Abb. Title page En Opus Musicum). In turn, Glarean paid Senfl a compliment that he would undoubtedly have cherished when he observed that the latter had “attained a distinguished name among composers, and one not at all unworthy of his master Heinrich Isaac”.[50] Isaac had become a benchmark by which to judge those that followed.

[45] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 89–130; Burn 2006.

[46] Strohm, in Strohm/Kempson 2001. On Isaac’s pupils, see Picker 1991, 15 f. On Senfl, see » G. Ludwig Senfl.

[48] Bente 1968; with important revisions in Lodes 2006. Most of the books are viewable at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[49] D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–38, all consultable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[50] Glarean 1547, 261; cited in Picker 1991, 15.

Heidrich 1993 | Hell 1985 | Rothenberg 2011b | Staehelin 2001

[1] Blackburn 1996, 21.

[2] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 19; Picker 1991, 4; Senn 1954, 10.

[3] More recent research confirms the date of c. 1476 originally proposed by Thomas Noblitt for the three motets, see » K. 7 The Codex of Nicolaus Leopold. » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154 is viewable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/; Isaac’s motets are on fol. 72v, fol. 73v, and fol. 74v. Modern edition: Noblitt 1987–1996. On dating, see Rifkin 2003, 294–307. On possible identities of the scribes, see Strohm 1993, 519 ff. (though doubted in Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103). See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[4] See, further, Strohm 1993, 526; Kempson 1998, esp. vol. 1, 29–35, 92–106; Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[5] Cumming 2011, with reconstructed score at 268–274.

[6] Relevant documents in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, after D’Accone 1961 and D’Accone 1963.

[7] Complete text given in McGee 1983.

[9] Modern edition of » D-LEu Ms. 1494: Gerber et al. 1956–1975.

[11] The authenticity of Comme femme has been disputed by some, but is accepted in Fallows 2001.

[13] See also Staehelin 1977, vol. 3, 81–86.

[15] Wegman 1996, esp. 461–469; Wegman 2011.

[16] Full document quoted in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 46 f.

[19] See further Burn/Gasch 2011; Strohm 2011.

[20] Especially the Trent Codices and the St. Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); Strohm 2011, 42 ff. and the literature cited there.

[21] It is difficult to specify how many feasts Isaac’s surviving mass propers could cover, given the multiple use of the common of saints, and the uncertaintly around the details of the liturgies for which Isaac composed. An estimate of around 150 days in the year seems reasonable.

[24] Glarean 1547, 460; trans. in Picker 1991, 17 f.

[25] It is generally agreed that the first and third volumes contain imperial music, and the second music for Konstanz; see Burn 2003. Rothenberg 2011a presents an alternative hypothesis.

[26] Among others, the monastery of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, and the monasteries of Neresheim and Ottobeuren; see especially Eichner 2011 and Rimek 2011.

[28] Digitised images of the manuscript, including the two autographs, are available at: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000. The “de manu sua” pieces are at fols. 8 ff., fol. 255v–256v, and fol. 294.

[29] Owens 1997, 258–290.

[30] The earliest mass “contra Turcos” is traceable to 1453/54; Jensen 2007, 117.

[31] The letter in which Du Fay mentions his laments is reproduced in Fallows 1982; Kirkman 2010, 121 f.

[32] Concordances to » D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (c. 1498–1500): D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 (Lalla hoe hoe; 1520s); » A-Wn Mus.Hs.18810 (La la hö hö; 1524–1533). D-B preserves the work in a longer form than the concordances, with a central section absent elsewhere. The longer form is most likely the original; transcriptions of the longer version in Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, and Just 1990/1991, vol. 3. For digitised images of D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 see: http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/view/cim/cim.html; for D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (the piece is at fol. 224v; piece No. 110): http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000.

[33] Somewhat similar is Isaac’s “motet on a fantasia called La mi la sol”, which he composed for a job-interview in Ferrara in 1502, though the basic material of La la hö hö is even more striking in its limitations, and not connected to the piece’s title through solmisation-syllables.

[35] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, passim.

[36] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 156; also Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, 38 n. 24.

[37] Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 255; Staehelin 1989 proposes that the original first word was not “Innsbruck” but “Zurück”.

[38] Strohm argues that he did in Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[39] Strohm 2014, 7.

[40] RISM 1539/27. This source is also now viewable online, at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00074418/images/?viewmode=1.

[41] Salmen 1997, 250.

[42] First in Ernst Ludwig Gerber’s Neues historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig 1812–1814); see Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 258.

[43] Drexel 1997, 285.

[45] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 89–130; Burn 2006.

[46] Strohm, in Strohm/Kempson 2001. On Isaac’s pupils, see Picker 1991, 15 f. On Senfl, see » G. Ludwig Senfl.

[48] Bente 1968; with important revisions in Lodes 2006. Most of the books are viewable at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[49] D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–38, all consultable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[50] Glarean 1547, 261; cited in Picker 1991, 15.