Schlaglicht: Heinrich Isaac‘s Introit Gaudeamus omnes in Domino for the Feast of Mary Magdalen

The form and pre-existent material of the introit

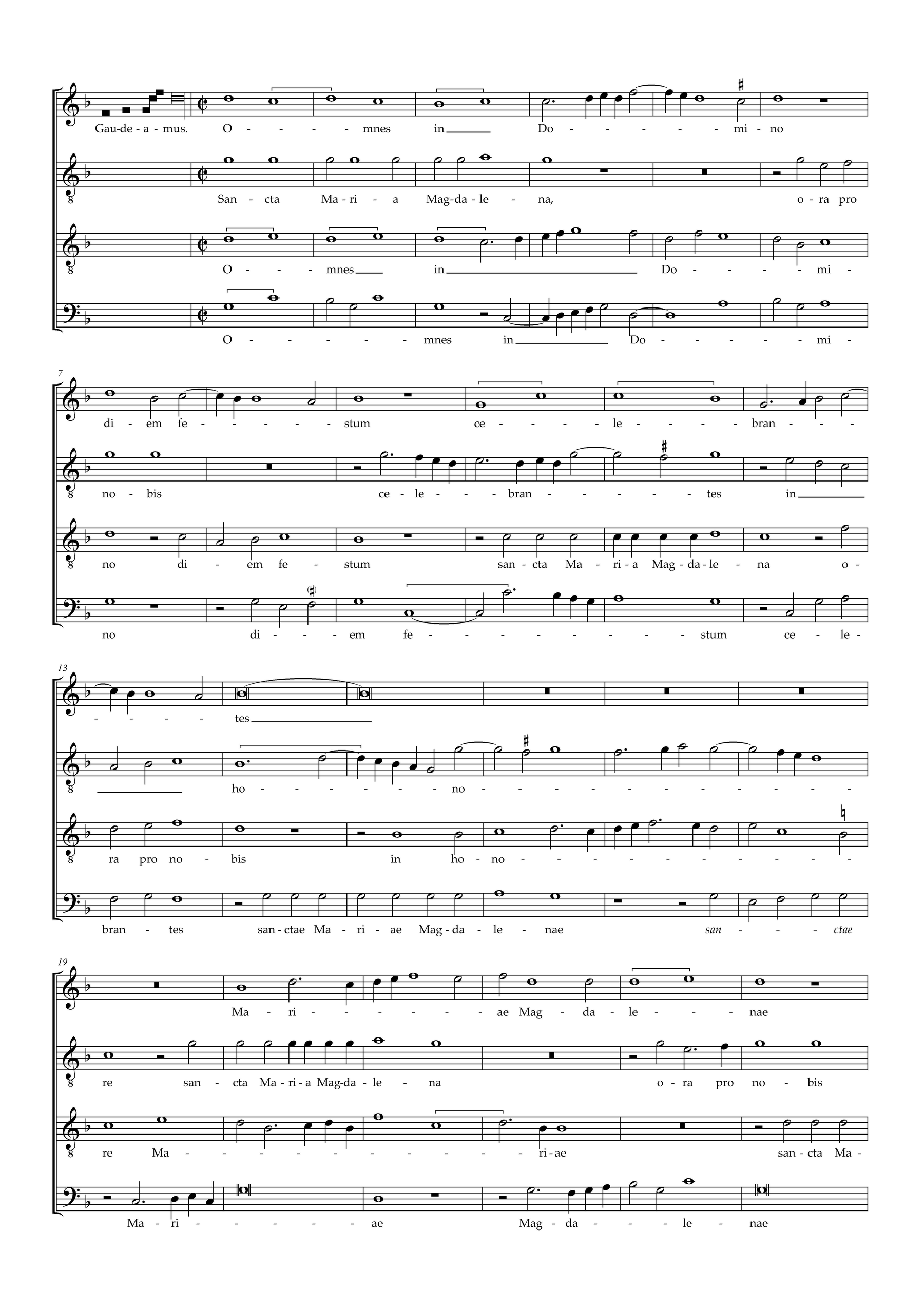

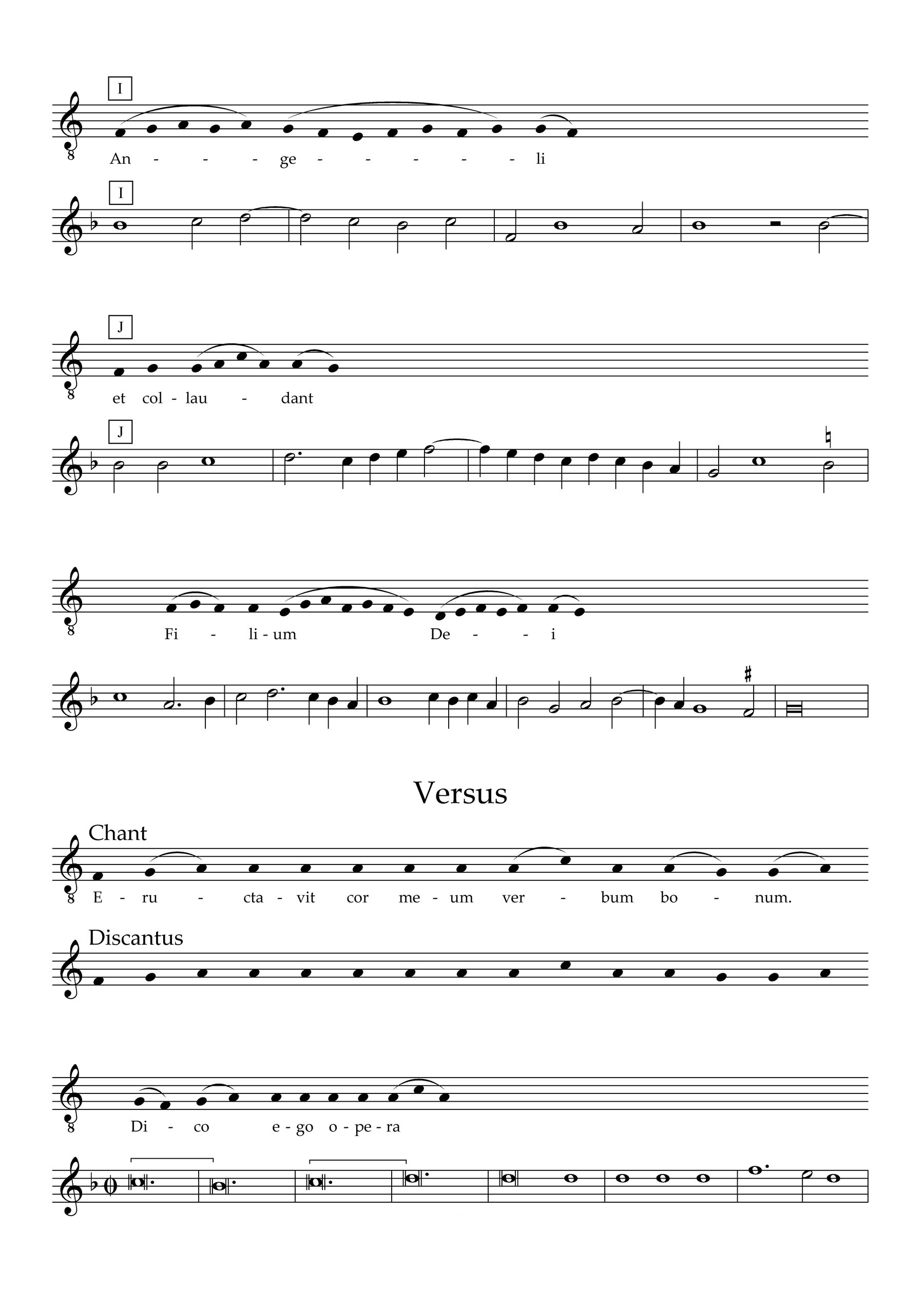

Like every piece in Isaac’s Choralis Constantinus (» I. Isaac’s “Amazonas”), the introit for the feast of Mary Magdalen (» Choralis Constantinus, II/14) is based on a pre-existent piece of Gregorian chant, from which it draws its overall form:

Introit antiphon – Opening intonation in chant (Gaudeamus); the remainder in polyphony

→

Psalm verse (Eructavit) – First half in chant; second half in polyphony

→

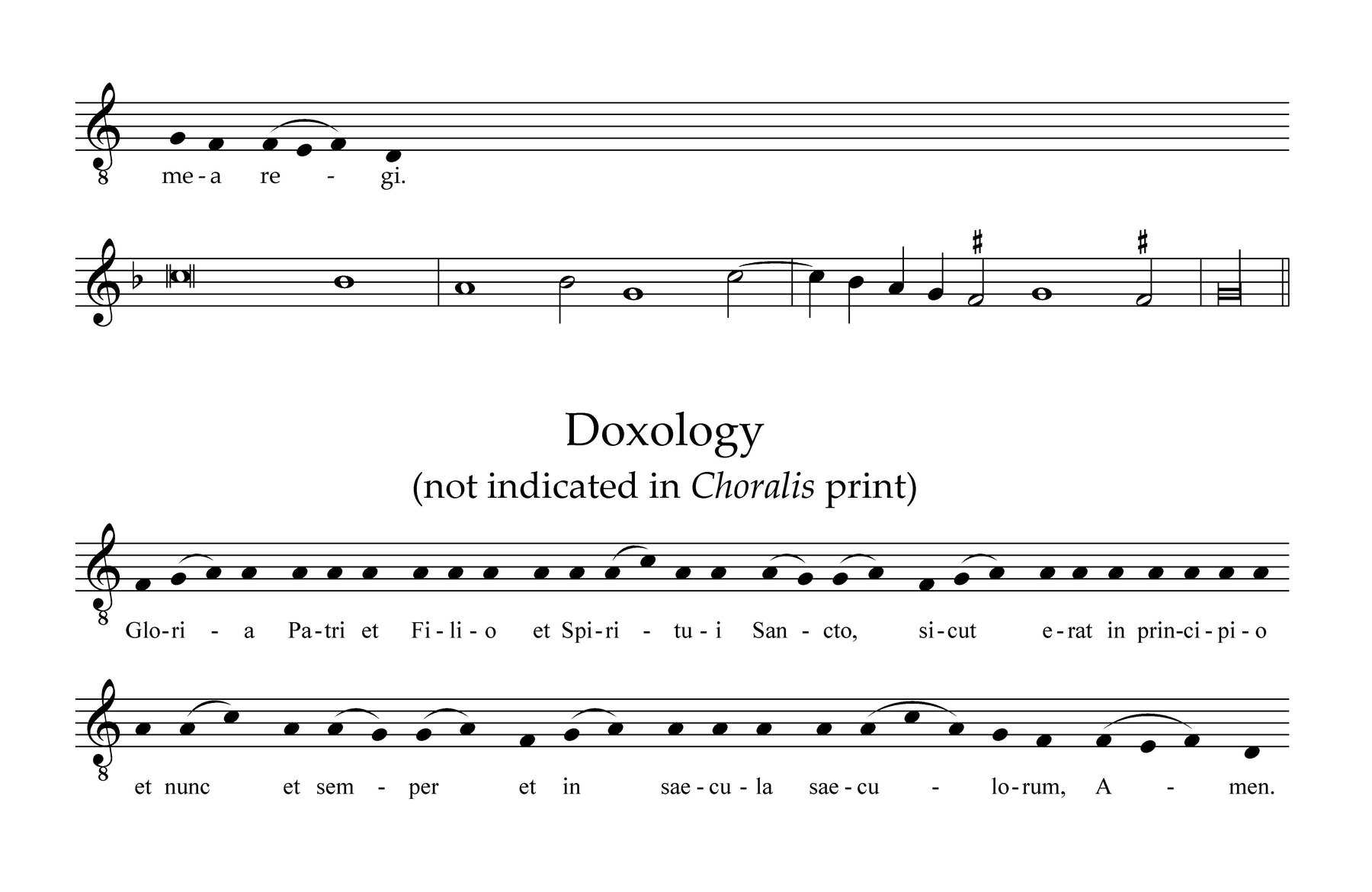

Doxology (Gloria patri) – Never indicated in the print, but must be added by convention

→

Repeat of Introit antiphon.

See » Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, Isaac, full score

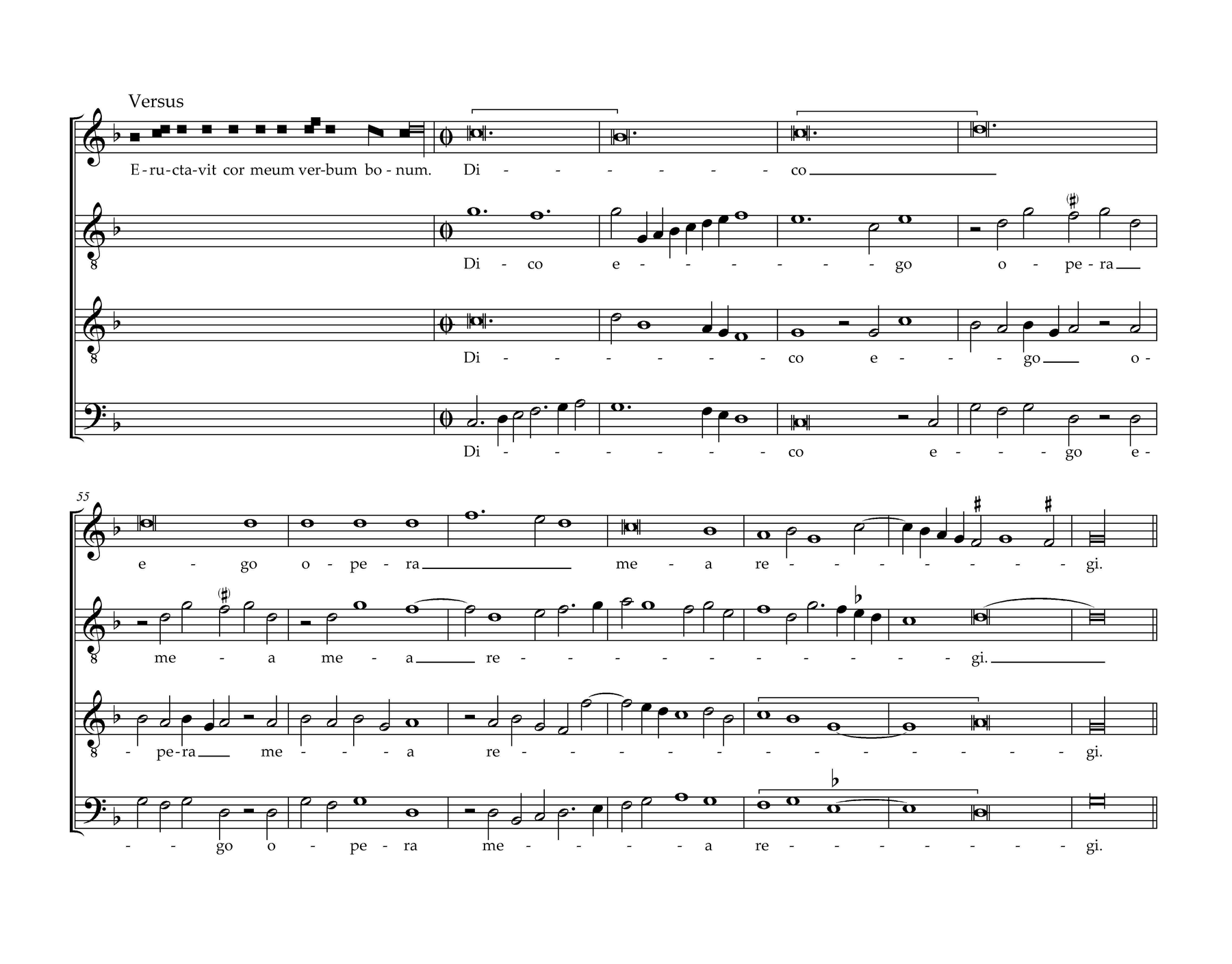

The chant of this introit, Gaudeamus omnes in Domino, was one of the most frequently used in the medieval liturgy. Indeed, the Choralis contains no less than eight different settings that Isaac composed for its various appearances on different feasts. Everyone attending mass on the feast of Mary Magdalen would have intimately known the words and the melody of this chant. As the choir began singing, they would have made constant comparison between the pre-existent material and the polyphony that they heard (» Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, chant).

The way that Isaac treated this chant varies enormously across the Choralis, in its division between the voices, its use to create imitative points, the degree of decoration, its rhythmic patterning, and the use of artifice such as canonic techniques. In the introit for Mary Magdalen, Isaac restricted chant-derived material more-or-less exclusively to the uppermost voice. The first-mode chant is transposed up a fourth, then assigned almost in its entirety to the discantus part. Another voice shares chant-derived material only once in the piece (» Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, chant, Phrase D).

Phrase structure and second chant in Isaac’s setting

The chant is a structured combination of melody and text, each built from intelligible units that Isaac seeked to preserve and emphasise in his setting. Examining how he did this reveals his role as both musical and textual interpreter. First, he used rests to create coherent phrases that follow the word-boundaries of the text. Within each of these phrases, his basic approach was to begin in semibreves that follow the chant exactly, then to move into smaller note-values towards the end, both adding light decoration, such as the filling-in of leaps, and simplifying very long melismas. Most phrases end with the standard renaissance upper-voice cadential formula, requiring some degree of departure from the chant. The quality of these cadences is determined by the lower voices. In almost every instance, Isaac maintained forward-motion through overt interruption or other kinds of incomplete cadencing. A firm halt in the home-key of G-Dorian occurs only at the very end of each section. For Isaac, it was important that his listeners (both human and heavenly) recognise not only the outlined chant-melody, but also its finer structural details. The chant contains an identical motif at three points (» Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, chant, phrases D, G and J). Isaac was careful to preserve this identity through the use of the same distinctive rhythmic-melodic pattern each time.

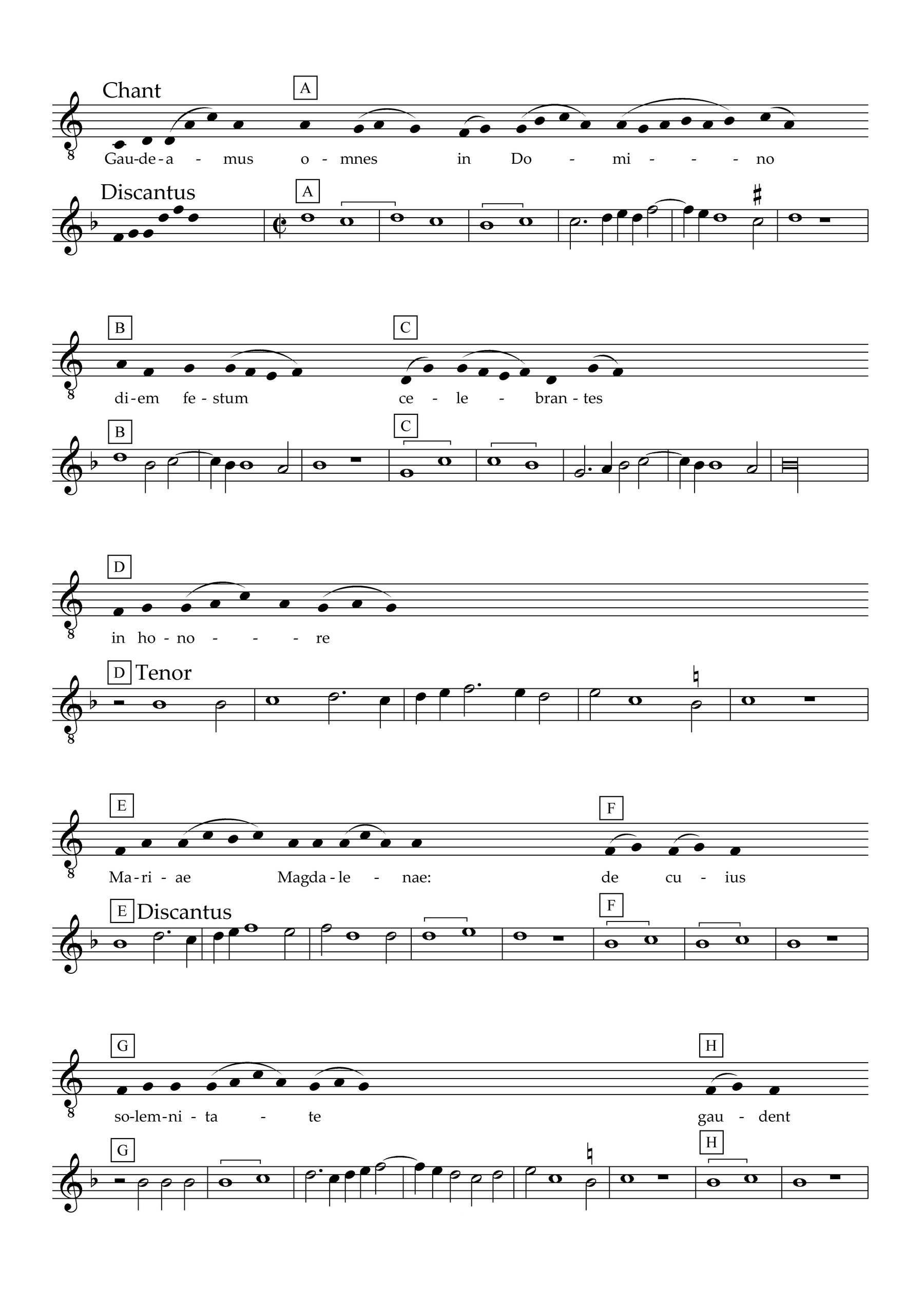

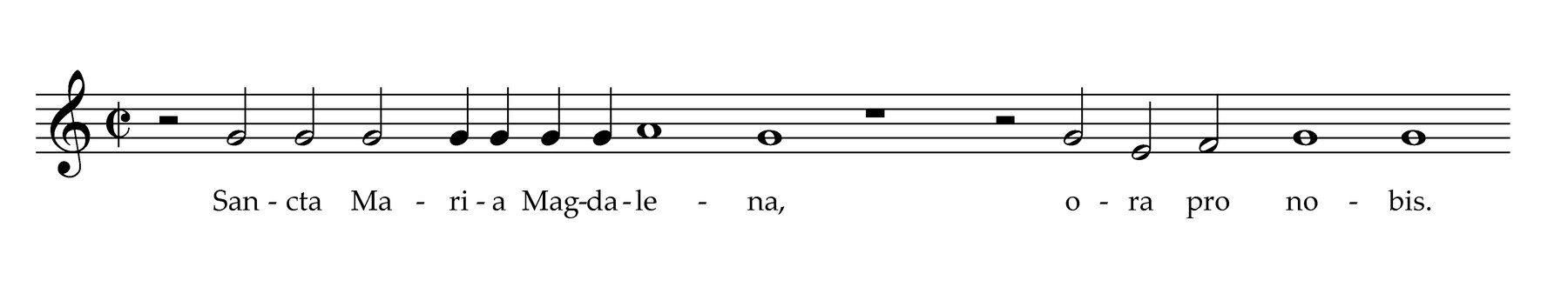

The restriction of chant material to the discantus voice is deliberate, resulting from Isaac’s decision to add an extra layer of meaning and solemnity to his setting: the lower voices incorporate a second borrowed melody, a litany formula pleading for Mary Magdalen’s intercession (» Notenbsp. Sancta Maria Magdalena, litany).

This use of a second borrowed melody is a tactic that Isaac often adopted with his settings of Gaudeamus, in order to make absolutely clear what feast is being introduced. He used it occasionally elsewhere too, for example, in the introit for Easter Day, which includes the Leise Christus surrexit (» B. SL Christ ist erstanden). The litany formula is present at the very start, in the alto voice, and is immediately apparent from its contrasting text. Thereafter, it passes systematically three times from altus to tenor to bassus. The rhythmic patterning, and, occasionally, the pitch-patterning as well, are subject to some variation in order to make correct counterpoint with the main chant. Nonetheless, the litany succeeds in preserving its distinctive identity by its use of syllabic declamation on repeated notes, usually crotchets, of the same pitch.

When not involved with the litany, the lower voices are usually in free, non-imitative counterpoint. Only once does a lower voice share in the main chant: the phrase “in honore” is not stated in the discantus at all, but taken by the tenor, whilst the discantus falls silent (» Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, chant, phrase D). The result is the only extended section of the piece in reduced scoring. Its purpose is less for its own sake than to provide a contrast against which to hear the subsequent discantus re-entry with the most important moment in the whole introit, the declaiming of Mary Magdalen’s name.

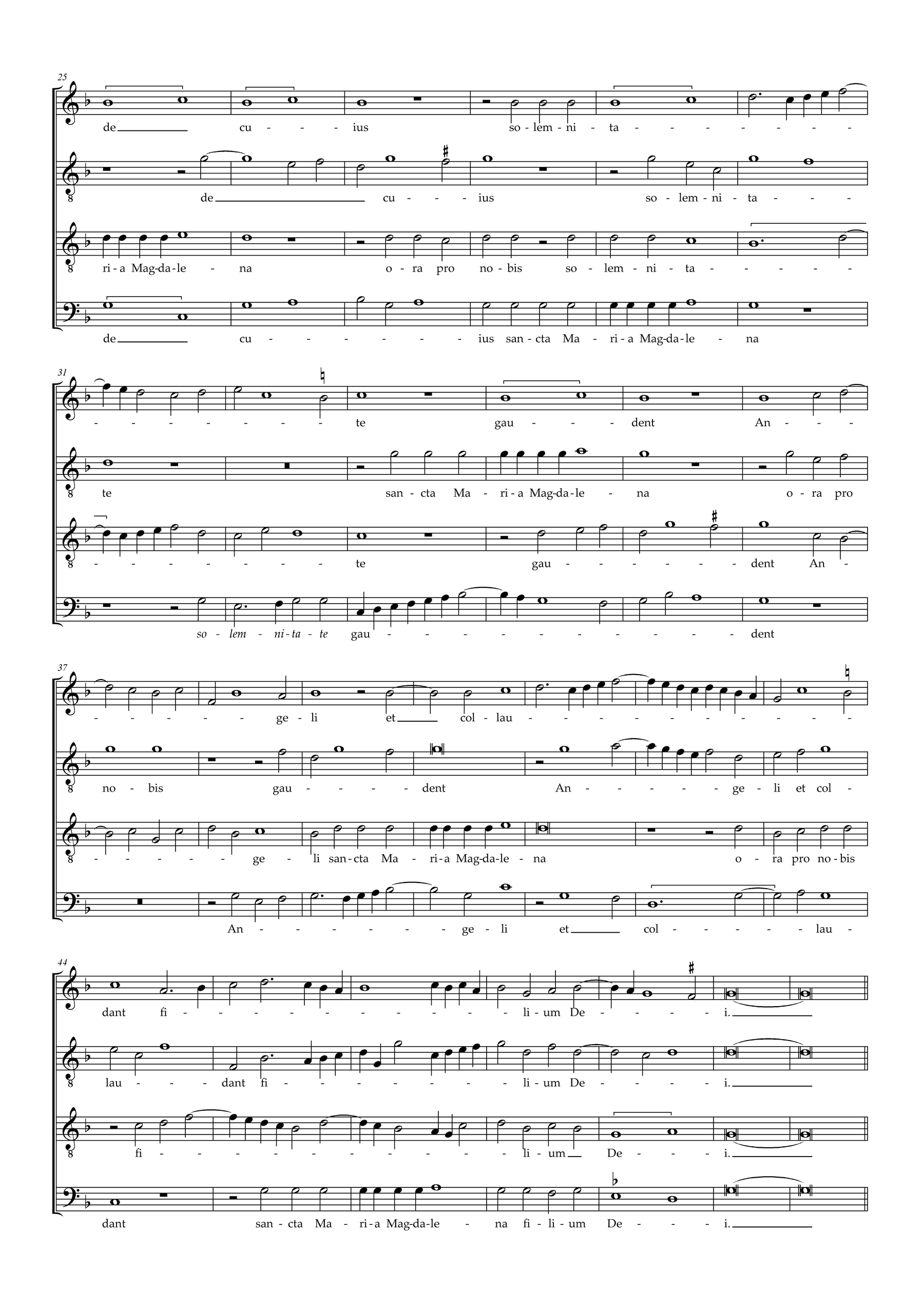

The introit verse

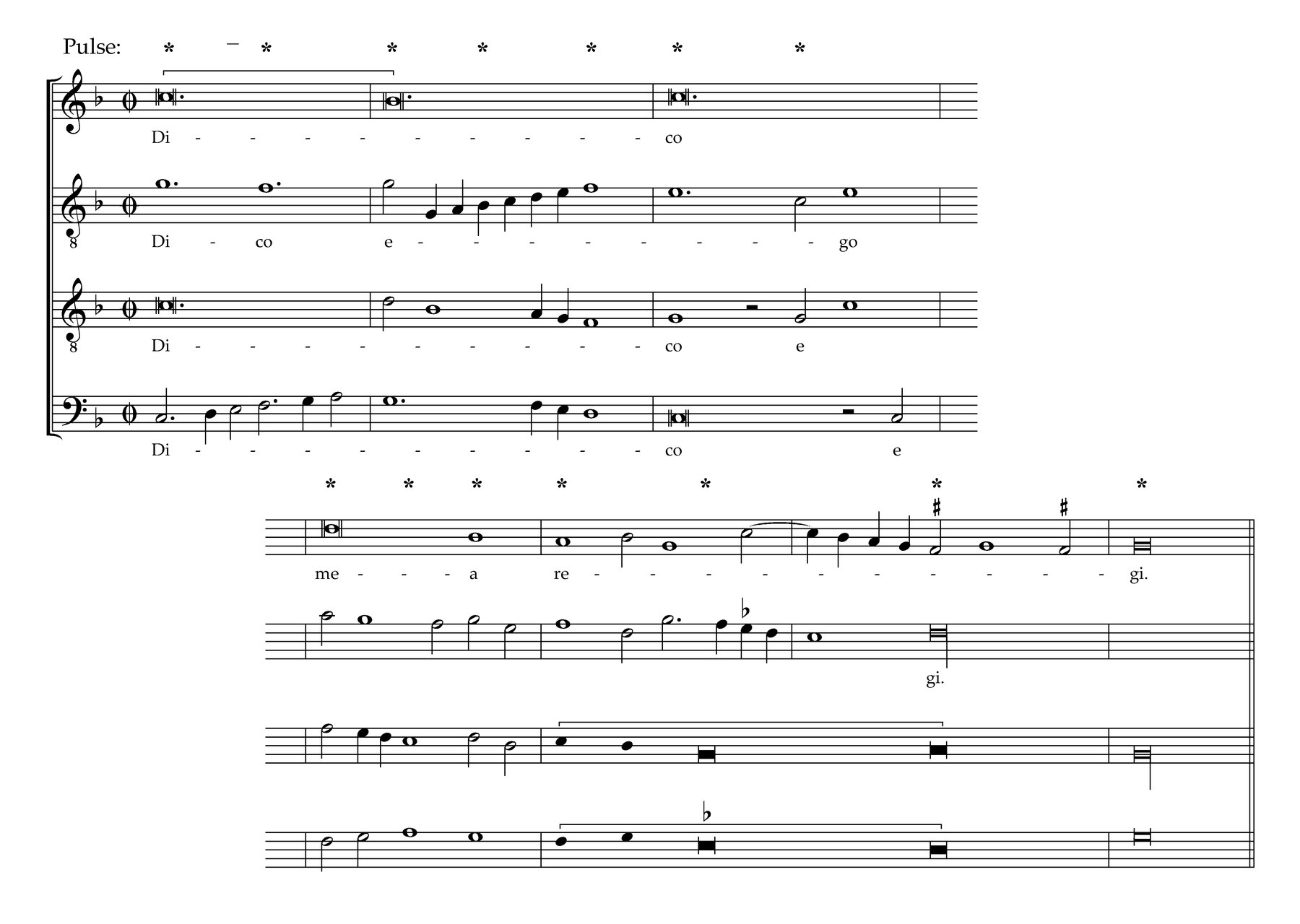

In introit verses, Isaac always left the first half in chant and set only the second half in polyphony. The verse’s chant material is of the simplest kind: a recitation formula shared by all introits in the same mode. Its special challenge is to make it interesting and distinctive. Isaac succeeded, in this instance, by using rhythmic liveliness. The verse makes use of simultaneous different time-signatures, a technique for which the Choralis has become notorious, although it only occurs in a fraction of the collection, and is but one of many devices that Isaac used to add rhythmic vitality (others include setting the chant in irregular units of, for example, five or seven beats, extended syncopation, and various kinds of cross-rhythm). In this case, the discantus is originally designed in halved note values in relation to the other voices: the lower voices are in Ø, whilst the discantus is in Ͽ (the signature given for the discantus in the print, ₵, needs correcting). In using this relationship, Isaac draws on an established practice for indicating his chant material, which, once more, is restricted to the discantus alone.

Although the proportional signature in the discantus should affect the way the singers accentuate the line, the relationship between the parts will nonetheless be completely inaudible to the listener. Isaac provided another layer of rhythmic variety that can be perceived by the ear alone: within the verse’s brief span, three different metres are heard. The compound duple pulse asserted in the opening bar is immediately contradicted in the next by a shift to simple triple groupings. This remains until towards the end, when a hemiola, with lively syncopation in the chant-derived discantus, heralds closure (» Notenbsp. Gaudeamus, pulse).

Isaac completed the effect of perpetual impetus by avoiding any cadential motion until the end, and by rapid motivic exchange between the altus and bass during the repeating pitches of the chant.

Isaac never intended this introit to stand in isolation. His prayer to Mary Magdalen asks her to listen not only to Gaudeamus itself, but also to the rest of the mass for her that it introduces, including both the remaining polyphonic propers, and the mass-ordinary (for which Isaac also made systematic provision). Within this whole liturgical framework, Isaac’s Choralis motets hang as beautiful ornaments, bringing greater intercessory power to singers, worshippers, and composer alike.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

David Burn: „Isaac‘s Introit for St Maria Magdalena “, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/kapitel/schlaglicht-heinrich-isaacs-introit-gaudeamus-omnes-domino-feast-mary-magdalen> (2016).