Turkish dervish-music and European counterpoint

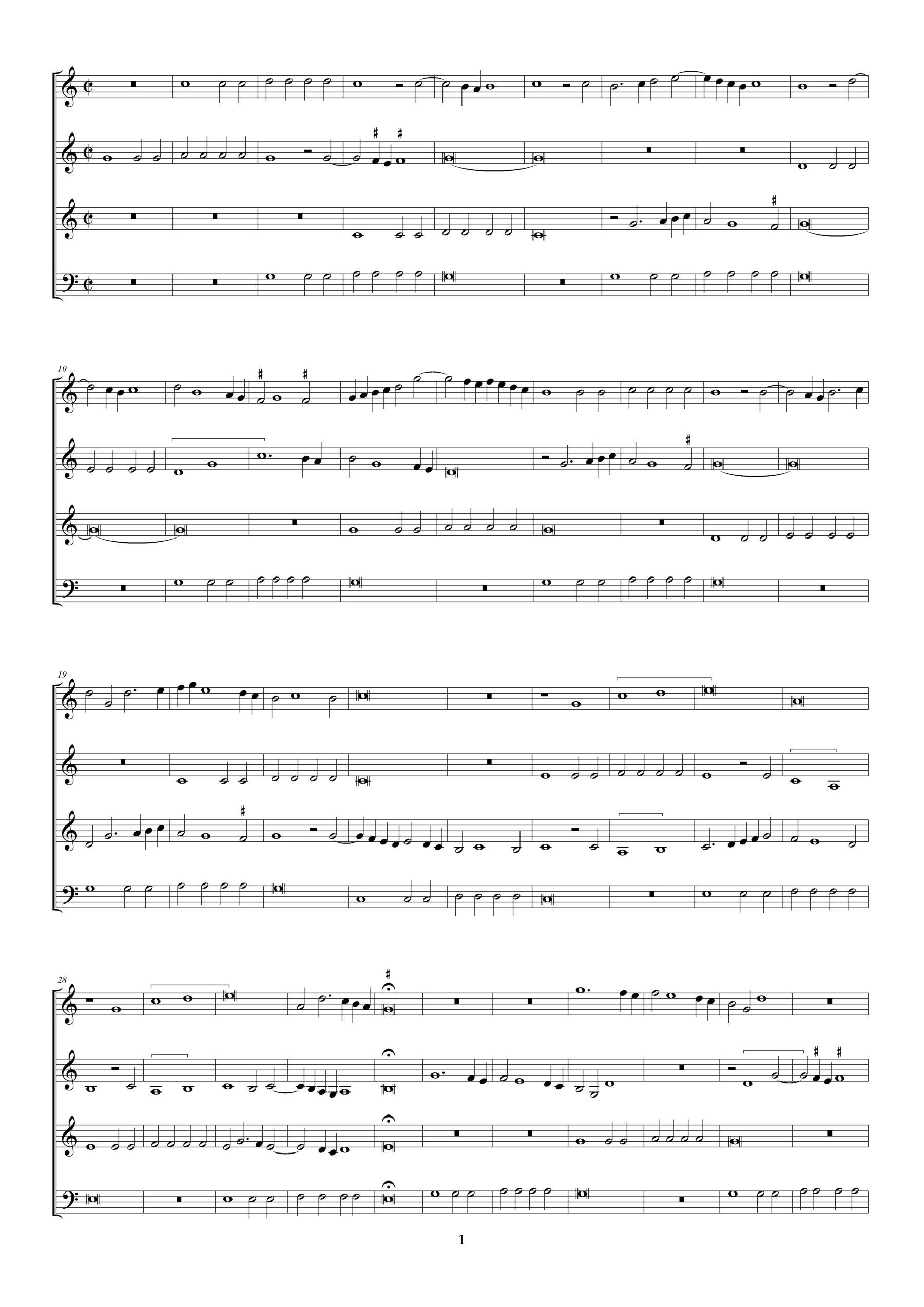

The traumatic effect of the fall of Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Empire, to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 is hard to overestimate. Turkophobia gripped European consciousness for centuries afterwards, crusades were regularly planned, and masses “against the Turks” (“contra turcos”) entered the liturgy with 300-year indulgences for those who celebrated them.[30] Guillaume Du Fay composed four laments on the fall shortly after the event (unfortunately only one now survives), [31] and the long tradition, stretching from the mid-fifteenth through the sixteenth century, of composing mass ordinary settings on the song L’homme armé may owe something to the situation. However, one of the most remarkable musical results of the West’s encounters with the Ottomans is Isaac’s piece usually known as La la hö hö, but called Allahoy in its earliest source.[32] The piece is based around obsessive repetitions of a short motif of two pitches, a step apart, both of which are repeated a number of times. The motif is almost continually present, and transposed to begin on an unusually wide variety of starting-notes (» Notenbsp. La la hö hö). These mark the piece out as curious, if not entirely without parallel.[33] (» Hörbsp. ♫ La la hö hö) What is truly extraordinary is the identification of the motif that inspired the work as a formula recited by Turkish dervishes (“Lā ilāha illa’llāh” – “no God other than Allah”).[34] No other composer in Isaac’s time is known to have been inspired by non-Western musical material.

How and where might Isaac have heard such a formula? The transmission of the piece exclusively in central-European sources suggests that he composed it during his time in the service of Emperor Maximilian I. The Emperor was obsessed with a crusade against the Turks, but this went (only superficially paradoxically) hand in hand with increased diplomatic contacts.[35] Isaac may have heard the formula during such a diplomatic encounter: the first, and most spectacular of these took place in Innsbruck in summer 1497, only shortly after he had entered imperial service. Maximilian welcomed (at Innsbruck) a Turkish embassy that stayed for several months, surrounded by extraordinary local excitement and interest.[36] It is equally possible that Isaac was told about Ottoman music-making by returning ambassadors that Maximilian regularly sent to Constantinople.

A solution to the origin of La la hö hö’s musical material surrounds the work in new mysteries. No surviving source has more than a text incipit, but does that mean that the piece was conceived for instruments rather than voices? The dervish formula is vocal, but if Isaac’s piece did have a text, what form may that have taken? Why did Isaac compose it at all? Purely personal interest seems unlikely, but what was its original context? Theatrical-dramatic? Honorific? Was the piece meant respectfully – perhaps even as a gift to Turkish diplomats – or mockingly? Only hypotheses can be offered in answers to these questions. The story of La la hö hö has an appropriately unexpected postscript: the piece was Christianized – perhaps unwittingly by a composer unaware of its origins – through use as the basis for a mass setting, the Missa Lalahe.

[30] The earliest mass “contra Turcos” is traceable to 1453/54; Jensen 2007, 117.

[31] The letter in which Du Fay mentions his laments is reproduced in Fallows 1982; Kirkman 2010, 121 f.

[32] Concordances to » D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (c. 1498–1500): D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 (Lalla hoe hoe; 1520s); » A-Wn Mus.Hs.18810 (La la hö hö; 1524–1533). D-B preserves the work in a longer form than the concordances, with a central section absent elsewhere. The longer form is most likely the original; transcriptions of the longer version in Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, and Just 1990/1991, vol. 3. For digitised images of D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 see: http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/view/cim/cim.html; for D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (the piece is at fol. 224v; piece No. 110): http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000.

[33] Somewhat similar is Isaac’s “motet on a fantasia called La mi la sol”, which he composed for a job-interview in Ferrara in 1502, though the basic material of La la hö hö is even more striking in its limitations, and not connected to the piece’s title through solmisation-syllables.

[35] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, passim.

[36] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 156; also Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, 38 n. 24.

[1] Blackburn 1996, 21.

[2] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 19; Picker 1991, 4; Senn 1954, 10.

[3] More recent research confirms the date of c. 1476 originally proposed by Thomas Noblitt for the three motets, see » K. 7 The Codex of Nicolaus Leopold. » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154 is viewable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/; Isaac’s motets are on fol. 72v, fol. 73v, and fol. 74v. Modern edition: Noblitt 1987–1996. On dating, see Rifkin 2003, 294–307. On possible identities of the scribes, see Strohm 1993, 519 ff. (though doubted in Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103). See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[4] See, further, Strohm 1993, 526; Kempson 1998, esp. vol. 1, 29–35, 92–106; Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[5] Cumming 2011, with reconstructed score at 268–274.

[6] Relevant documents in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, after D’Accone 1961 and D’Accone 1963.

[7] Complete text given in McGee 1983.

[9] Modern edition of » D-LEu Ms. 1494: Gerber et al. 1956–1975.

[11] The authenticity of Comme femme has been disputed by some, but is accepted in Fallows 2001.

[13] See also Staehelin 1977, vol. 3, 81–86.

[15] Wegman 1996, esp. 461–469; Wegman 2011.

[16] Full document quoted in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 46 f.

[19] See further Burn/Gasch 2011; Strohm 2011.

[20] Especially the Trent Codices and the St. Emmeram Codex (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); Strohm 2011, 42 ff. and the literature cited there.

[21] It is difficult to specify how many feasts Isaac’s surviving mass propers could cover, given the multiple use of the common of saints, and the uncertaintly around the details of the liturgies for which Isaac composed. An estimate of around 150 days in the year seems reasonable.

[24] Glarean 1547, 460; trans. in Picker 1991, 17 f.

[25] It is generally agreed that the first and third volumes contain imperial music, and the second music for Konstanz; see Burn 2003. Rothenberg 2011a presents an alternative hypothesis.

[26] Among others, the monastery of St. Ulrich and Afra in Augsburg, and the monasteries of Neresheim and Ottobeuren; see especially Eichner 2011 and Rimek 2011.

[28] Digitised images of the manuscript, including the two autographs, are available at: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000. The “de manu sua” pieces are at fols. 8 ff., fol. 255v–256v, and fol. 294.

[29] Owens 1997, 258–290.

[30] The earliest mass “contra Turcos” is traceable to 1453/54; Jensen 2007, 117.

[31] The letter in which Du Fay mentions his laments is reproduced in Fallows 1982; Kirkman 2010, 121 f.

[32] Concordances to » D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (c. 1498–1500): D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 (Lalla hoe hoe; 1520s); » A-Wn Mus.Hs.18810 (La la hö hö; 1524–1533). D-B preserves the work in a longer form than the concordances, with a central section absent elsewhere. The longer form is most likely the original; transcriptions of the longer version in Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, and Just 1990/1991, vol. 3. For digitised images of D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328-331 see: http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/view/cim/cim.html; for D-B Mus. ms. 40021 (the piece is at fol. 224v; piece No. 110): http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00012DA900000000.

[33] Somewhat similar is Isaac’s “motet on a fantasia called La mi la sol”, which he composed for a job-interview in Ferrara in 1502, though the basic material of La la hö hö is even more striking in its limitations, and not connected to the piece’s title through solmisation-syllables.

[35] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, passim.

[36] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 156; also Staehelin/Neubauer 1991, 38 n. 24.

[37] Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 255; Staehelin 1989 proposes that the original first word was not “Innsbruck” but “Zurück”.

[38] Strohm argues that he did in Strohm/Kempson 2001.

[39] Strohm 2014, 7.

[40] RISM 1539/27. This source is also now viewable online, at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00074418/images/?viewmode=1.

[41] Salmen 1997, 250.

[42] First in Ernst Ludwig Gerber’s Neues historisch-biographisches Lexikon der Tonkünstler (Leipzig 1812–1814); see Lindmayr-Brandl 1997, 258.

[43] Drexel 1997, 285.

[45] Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 89–130; Burn 2006.

[46] Strohm, in Strohm/Kempson 2001. On Isaac’s pupils, see Picker 1991, 15 f. On Senfl, see » G. Ludwig Senfl.

[48] Bente 1968; with important revisions in Lodes 2006. Most of the books are viewable at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[49] D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–38, all consultable online at: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/ausgaben/uni_ausgabe.html?projekt=1257941718&recherche=ja&ordnung=sig.

[50] Glarean 1547, 261; cited in Picker 1991, 15.