The Codex of Magister Nicolaus Leopold

A music collection spanning half a century

The ‘Leopold’ codex (Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. 3154) offers a fascinating insight into some of the polyphonic music that was performed for civic and princely patrons in Austria, Germany and northern Italy in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. As is typical for this time and region, much of the repertory was not of local origin, but had been composed by musicians from the Low Countries.

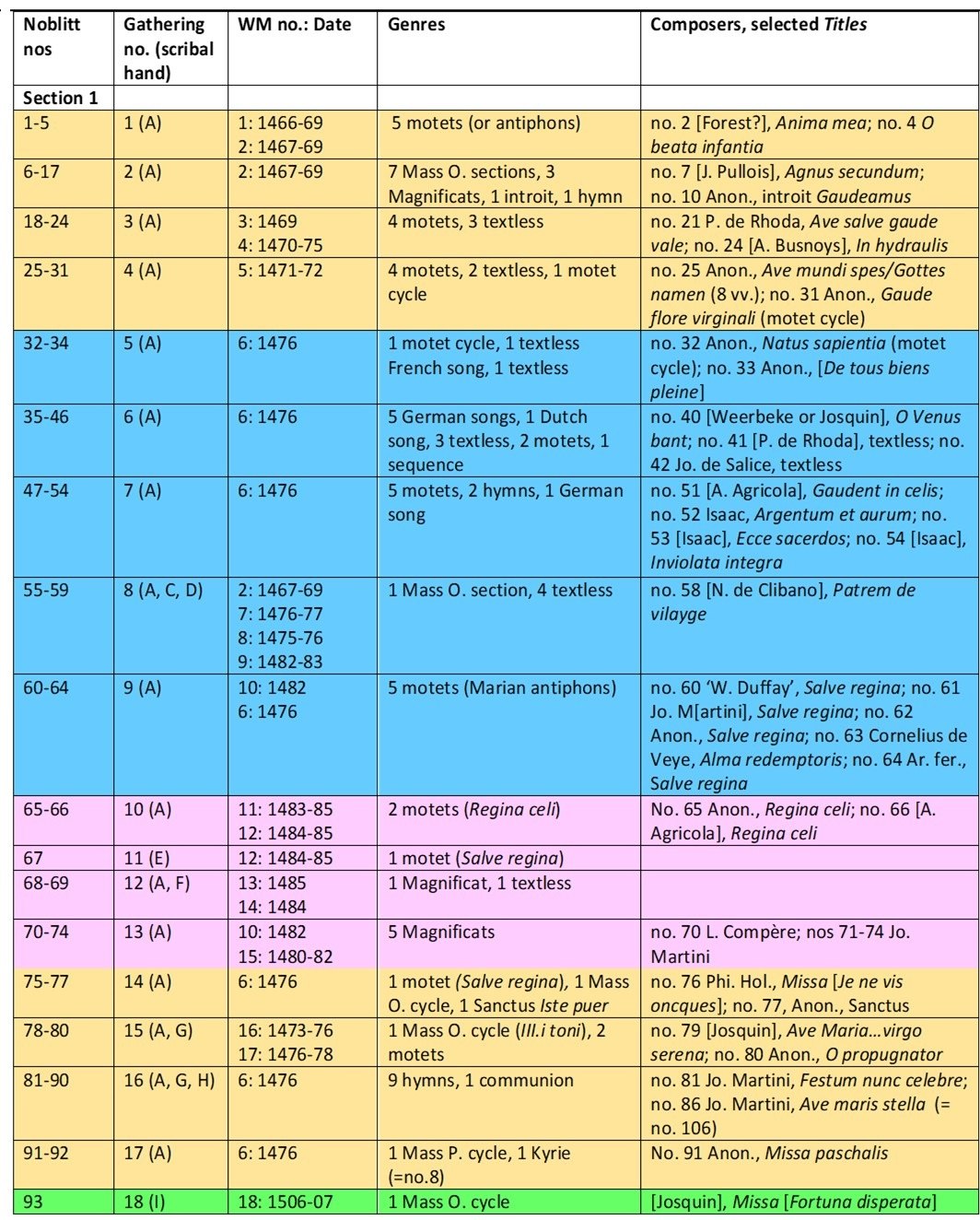

Although the codex is modest in format (it is a small folio manuscript measuring about 315 x 220 mm), its volume is considerable: on 472 paper folios it contains 174 musical compositions, counting cyclic Masses as single items and including both versions of four works that were each copied twice. It is clear that a substantial amount of further material has been lost.[1] All this music was written out by more than 40 different scribes between about 1466 and 1511,[2] and it is probable that most of it was copied in Innsbruck itself, with possible insertions coming from other centres in the Holy Roman Empire.

The manuscript consists of two independent sections, whose folios were originally numbered separately as fols [1]-200 and 1-297 respectively; this numbering system is datable to the period around 1500.[3] The first 19 folios were lost before a single continuous foliation of 1-178 and 179-471 was entered in the nineteenth century. The first section (fols 1–178, using this more recent continuous foliation) is mostly the work of a single scribe, with a few additions by others. Frequently, compositions are copied across the divide between gatherings. The second section (fols 179–471), however, is made up of individual gatherings, or units of 2-3 gatherings, that were evidently brought together from a variety of sources before being combined with the first section as a single book. These units in the second section each contain either a single large-scale work or a series of related works copied usually by a single scribe, often followed by one or more shorter pieces not always copied by the same scribe. Many of the individual gatherings or units seem to have been used separately before being bound together.

The codex was acquired in 1874 by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, through its librarian, Julius Joseph Maier, who created the first continuous foliation and numeration of the contents. Scholarly studies of the manuscript, beginning in the 1920s with explorations and editions of individual works, culminate in the complete four-volume edition of the music (with certain works presented only in facsimile) by Thomas L. Noblitt,[4] who also contributed several research essays on the repertory.[5] The codex has been used for the modern critical editions of its major composers - Obrecht, Isaac, Josquin, Compère and others - and its music has been widely recorded.[6] Recordings made for Musikleben are: »Hörbsp. ♫ Anima mea, ♫ Argentum et aurum, ♫ Ave mundi spes Maria, ♫ Es sassen höld, ♫ Gespile, liebe Gespile gút, ♫ Ich sach einsmals, ♫ Kyrie Pascale Les haulz et es bas, ♫ Kyrie Pascale Stimmwerck, ♫ O propugnator, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer. 1, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer 2, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer 3, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer 4, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer 5, ♫ Salve regina Ar. fer. 6, ♫ So steh ich hie, ♫ Tannhauser.

Innsbruck and its Church of St Jacob

The parish church of St Jacob, Innsbruck (the predecessor of the present-day baroque cathedral) is the institution where at least some parts of the Leopold codex were most probably used. St Jacob’s was the ecclesiastical centre of the town, which since 1420 had been the main residence of the Dukes of Austria in the county of Tyrol. The church was adjacent to the ducal palace (the ‘Mitterhof’, see » Abb. The ducal court of Innsbruck) and is today enclosed within its precincts, the Hofburg.[7] Friedrich III (Holy Roman Emperor 1452–93) had been born at Innsbruck in 1415; his cousin Archduke Siegmund (or Sigismund) was born there in 1427 and ruled the Tyrol from 1446 until his resignation in 1490. Innsbruck also became an important centre for Siegmund’s successor, Maximilian I (King of the Romans 1486, Holy Roman Emperor 1508, d. 1519), after he took control of Tyrol in 1490.[8] At his command, the famous Goldenes Dachl (Golden Roof) of Innsbruck was built to commemorate Maximilian’s wedding to Bianca Maria Sforza, which was celebrated here in 1494 (» I. Kap. The arrival of Bianca Maria). Completed in 1500, it is a balcony roofed with fire-gilded copper tiles, from which the couple could observe pageants taking place in the square below (» Abb. The Innsbruck palace).

Magister Nicolaus Leopold

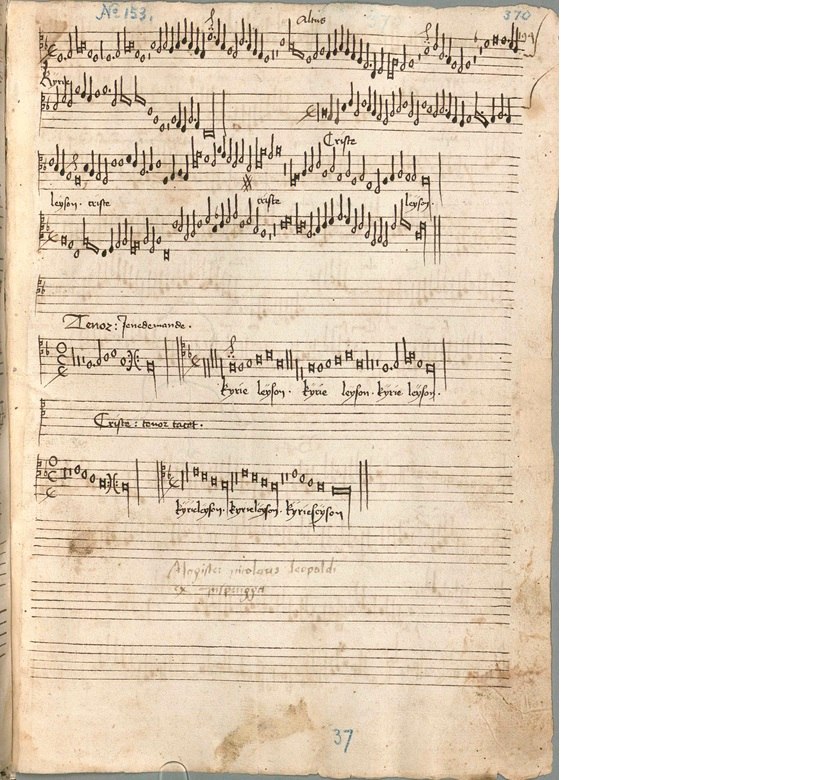

The manuscript D-Mbs Mus. Ms. 3154 is named after the schoolmaster Nicolaus Leopold of Innsbruck, whose autograph exlibris appears on the first page of three of the gatherings (fols 264r, 370r and 444r; » Fig. Magister Nicolaus Leopold’s exlibris).

Leopold probably owned at least those gatherings of the manuscript (gatherings 27, 37 and 47) in which he wrote his name (no other exlibris is found in the codex), and it is possible that he was also responsible for collecting the rest of the material and for having it bound together as a book. This could not have happened before about 1508. As Ewald Fässler has shown, Nicolaus was the son of the Innsbruck citizen, innkeeper and later town councillor Heinrich Leopold, who had moved from Münchberg (Upper Franconia) to Innsbruck, where he married in 1487 or 1488; even if Nicolaus was Heinrich’s first-born son, he cannot have been older than about 20 by 1508.[9] Yet by 1511 he was already the schoolmaster of St Jacob’s church and is recorded in the accounts of the Tyrolian government as follows:

Maister Niclasn Leopold, Schuolmaister hir, geben am XII. tag October für procession, begrebnus, bestattung, sybenden und dreyßigsten weyland meiner allergenedigisten frauwn der Romischen Kayserin gehalten. Laut Seiner quittung VI gulden.[10]

(Given to Magister Nicolaus Leopold, schoolmaster here, on 12 October [1511] for procession, requiem service, funeral, seventh and thirtieth [days?] of my most gracious lady deceased, the Roman Empress. According to his receipt, 6 fl.)

Empress Bianca Maria had died on 31 December 1510 and was buried in the Cistercian abbey of Stams. This belated payment to schoolmaster Leopold may include commemoration services on the seventh and thirtieth days after her death. The task of directing the music for courtly funeral and memorial services was traditionally entrusted to musicians of St Jacob’s. Wolfgang Unterstetter, schoolmaster 1465-1478 (or until 1485, see Kap. Institutions, scribes and patrons), and Nicolaus Krombsdorfer, who in 1463-1470 was organist, then court chaplain and finally parish priest (d. 1488),[11] were regularly rewarded in the context of such services (» D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck). The income of these school and court musicians was, as in similar establishments elsewhere, a patchwork of regular or casual payments from the court, church benefices, income from special endowments for ceremonies and funerals (Jahrtage), and teaching fees.

In view of Leopold’s young age, it is not surprising that no earlier documents mention him in the role of schoolmaster at Innsbruck.[12] He had obtained the university degree of magister by 1511, as was presumably required for his position. By 1515, Leopold even possessed a doctorate in law and was accepted for a canonry at the cathedral of Brixen/Bressanone. In 1518, having also taken lower ecclesiastic orders, he was admitted as canon there.

A number of school and university teachers in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries owned compilations of polyphonic music, at least partly for use as teaching aids. Hermann Pötzlinger, whose large library included the ‘St Emmeram codex’ (» D-Mbs Clm 14724), was schoolmaster at the abbey of St Emmeram at Regensburg from 1448 to his death in 1469 (» G. Hermann Poetzlinger); Johannes Wiser, who copied most of the Trent codices 90, 88, 89 and 91 (» I-TRbc 90, I-TRbc 88, 89, 91), was schoolmaster of Trent cathedral 1458-1465. Other schoolmasters who copied or owned music collections that are still extant were H. Battre (Ciney nr. Namur, 1430s), Peter Schrott (Trent, 1460s and 70s) and Johannes Greis (Benediktbeuren abbey, 1495).[13] Nikolaus Apel, owner of the codex » D-LEu Ms. 1494 (Leipzig, c.1490-1510), was at some time rector of Leipzig university.

How Leopold and his predecessors may have used the manuscript is not precisely known. Singers performing under their direction would have had difficulties in reading directly from these copies, either before or after the 48 gatherings had been bound together (» Kap. Page layouts in the Leopold codex). There are signs (especially in the second section of the manuscript) that this collection should primarily be regarded as a set of archival or teaching copies.

Genres and composers in the Leopold codex

Most of the music in the Leopold codex is sacred and Latin-texted, though a few secular works are also present. The codex contains three plenary Mass cycles (consisting of sections of both the Ordinary and the Proper of the Mass; a fragment of one of these is also copied elsewhere in the codex) and 21 Mass Ordinary cycles (one of which is copied twice), along with 11 independent Mass Ordinary sections (one copied twice), two motet cycles (of which each item functioned as a substitute for a Mass Ordinary section), three cycles of polyphonic Mass Propers (in addition to those incorporated in the plenary cycles already mentioned) and 29 independent Mass Proper items. 44 pieces are motets or antiphon settings, 14 are Vespers hymns (one copied twice), 11 are Magnificat settings, and two are settings of responsories There are also nine secular pieces (seven German, one Dutch and one textless but derived from a French polyphonic song) and 21 untitled and textless works, mostly of the motet type. Several works are fragments, either because they were left incomplete by the scribe or because pages are missing from the manuscript; some fragments only repeat music copied elsewhere. (See » Abb. Synopsis of the Leopold codex.)

In only 23 cases did the copyist attach a composer’s name, the remainder being copied anonymously. For another 28 works the composers can be ascertained from external concordances. Thus more than two thirds of the compositions remain anonymous to us. Of the 22 identifiable composers, the most prominent are Henricus Isaac with seven works (four of which are attributed in the manuscript), Johannes Martini also with seven (all attributed) and Jacob Obrecht with six (three attributed). Setting aside modern tentative ascriptions (for example to Paulus de Rhoda),[14] no other named composer was responsible for more than two pieces at most. This is the case, remarkably, with composers as notable as Josquin Desprez, Loyset Compère, Gaspar van Weerbeke, Alexander Agricola, Heinrich Finck and Thomas Stoltzer; among the remaining identified authors there are a few more foreigners (Jean Pullois, Antoine Busnoys, ‘Ar. Fer.’, Phi. Hol., Ninot le Petit, Nicasius de Clibano, Antoine de Févin) and lesser-known musicians perhaps of Central European origin (Aulen, G. Jung, W. Raber, Paulus de Rhoda, Cornelius de Veye, Jo. de Salice). Admittedly, compositions by the most renowned masters of the period – usually hailing from the Franco-Flemish region – may still be hidden among the anonyma (the anonymous Missa Je ne fays, no. 140, has only recently been identified as Isaac’s):[15] but we must assume that many other local or regional musicians contributed to the collection.

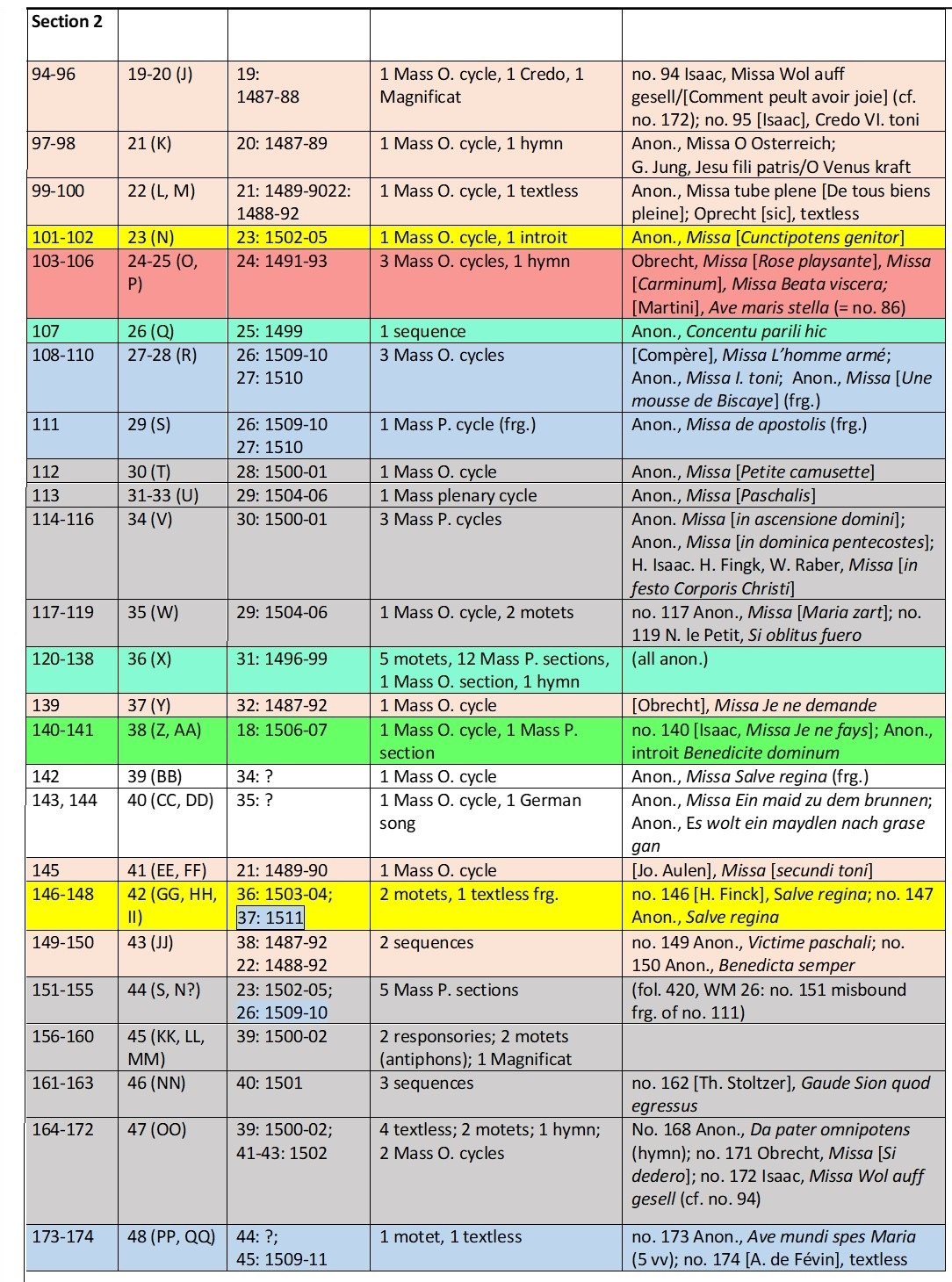

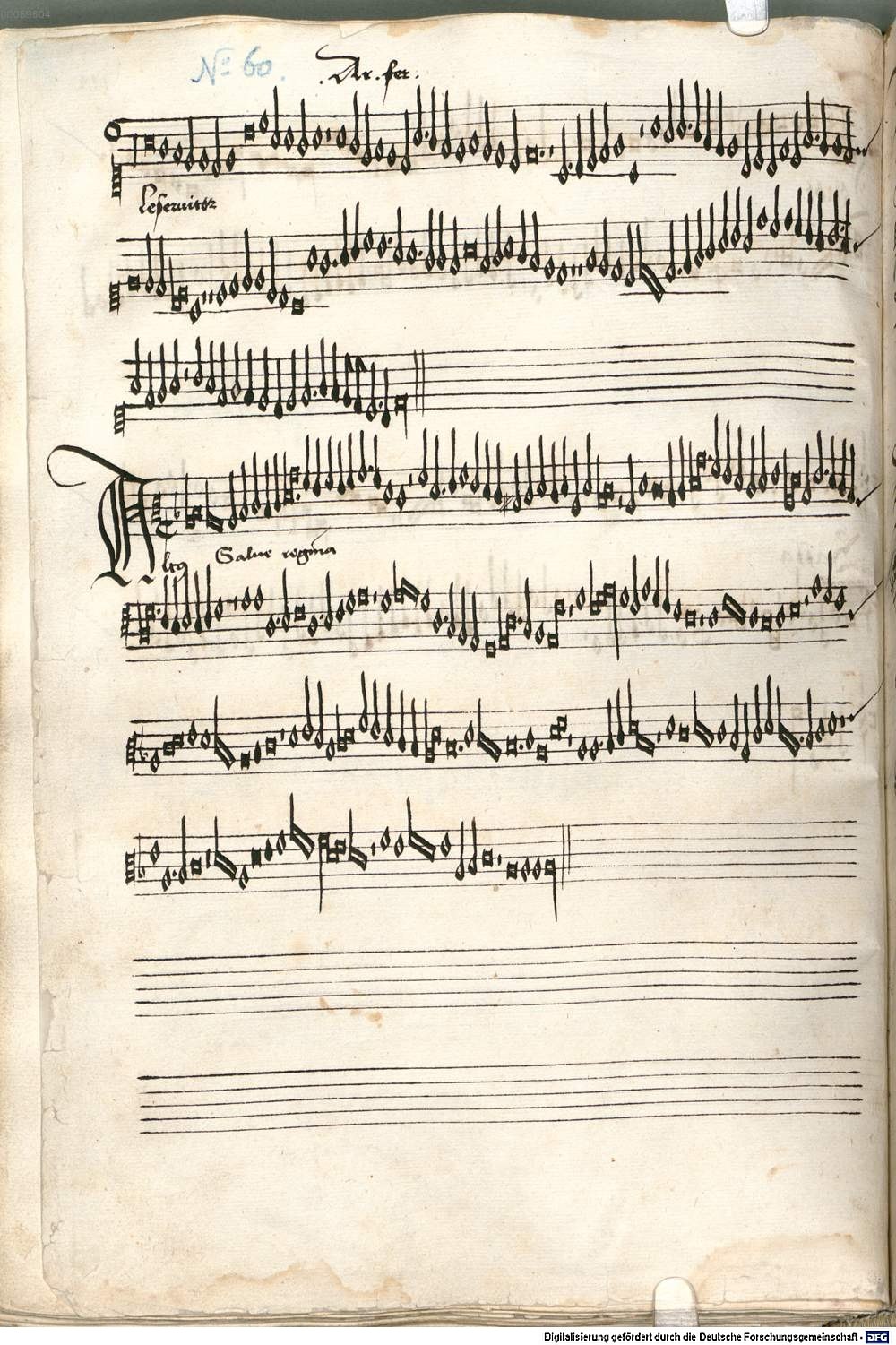

Only two attributions in the manuscript seem erroneous. The name of ‘Josquin’ appears above the much-circulated Missa L’homme armé by Loyset Compère (no. 108). A substantial four-voice Salve regina (no. 60) bears the name ‘Wilhelmus duffay’ (» Abb. Salve regina ‘Wilhelmus duffay’), an attribution that has been challenged.[16]

The setting is stylistically quite unlike Guillaume Du Fay’s known antiphon settings, but seems to belong to a Franco-Flemish composer of the mid-fifteenth century.[17] Only Compère, Isaac and Martini can be associated with music found in both sections of the codex. Both works by Josquin, the immortal Ave Maria…virgo serena and the Missa Fortuna desperata, are present in the first section, but only because the Mass cycle was appended to the end of the first section long after its completion; it was copied c.1506-07 by a single hand (‘I’) not seen elsewhere in the codex, and is contained within a gathering of its own, as is typical for the organisation of the second section.[18]

Organisation by genres and gatherings

The compilers occasionally attempted to group compositions of the same genre together.[19] German songs are clustered in gathering 6, Marian antiphons in gatherings 9-11, Magnificat in 12-13, hymns in 16, Mass Proper items in 36. Elsewhere, however, genres are mixed indiscriminately. The work of scribe ‘A’ (fols 1-171) was a sustained and systematic effort to produce a substantial collection of music; no other scribe made such a large contribution. In this phase of the compilation, the music seems to have been drawn from a larger body of exemplars rather than entered piecemeal as and when new pieces arrived. In the first section there are eight instances of a work being begun towards the end of a gathering and completed at the beginning of the next gathering: usually a sign that a longer sequence of pieces was envisaged. Where this happens in the second section, it is to accommodate extended Mass cycles which in any case required more than one gathering. Gatherings linked in this way were generally preserved, foliated and bound in the correct order, but the fact that gatherings 1 and 3 begin with incomplete compositions, and gathering 7 ends with one, suggests that not all of the music that was copied ended up in the manuscript – some gatherings are missing.

In the second section, each gathering or group of gatherings contains one or more lengthy works (usually Mass cycles); the remaining space is then often filled up with shorter works. Empty or even unruled pages, however, are frequently seen at the beginnings and ends of gatherings. Gatherings 24-25 (fols 236-253) are used for three Mass cycles by Obrecht: the Osanna and Agnus dei of the Missa [Rose playsante] on fols 236r-237r, the complete Missa [Plurimorum carminum II] on fols 237v-245v and the complete Missa Beata viscera on fols 246r-253r, all copied by a single scribe. One may surmise that this scribe was preparing a collection of Obrecht’s Masses, and that the gathering containing the beginning of the Rose playsante cycle and any that may originally have preceded it must then have been lost or discarded for unknown reasons.

Page layouts in the Leopold codex

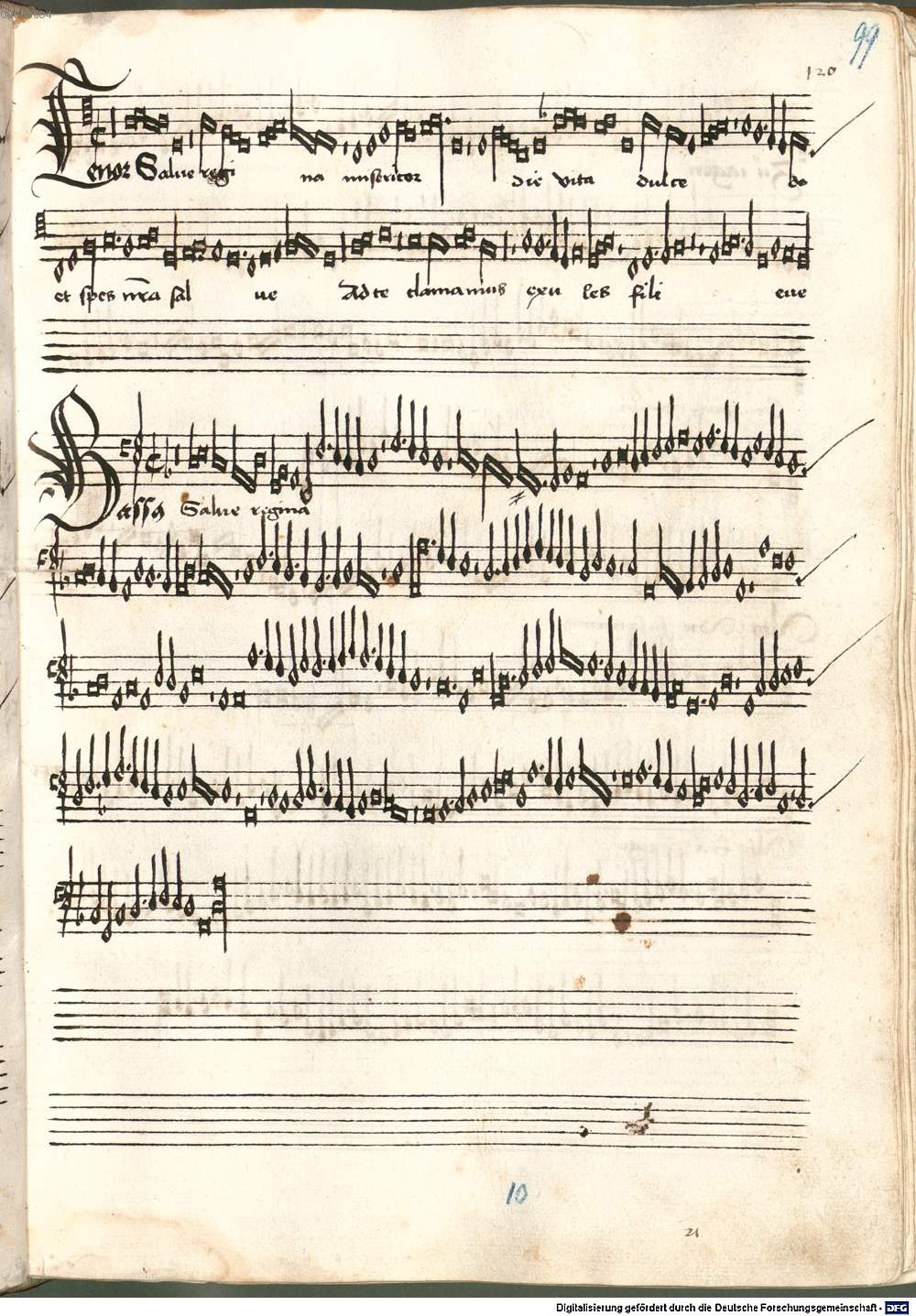

Most of the music in the Leopold codex is – typically for the period – in four parts, though a three-part texture is also common. A few works are in five parts, and a handful are in only two, while the anonymous eight-part motet Ave mundi spes/Gottes namen on fols 29v-30r and Isaac’s six-part Missa Wol auff gesell/Comment peult avoir joye (copied twice on fols 179r-196r and 456v-463v) are exceptional. Usually (but not invariably) an entire gathering was ruled with staves in advance, using either a straight-edge or a rastrum (a ‘rake’: a pen with five nibs that could produce an entire stave at once), before any music was copied into it. A unit of music would normally occupy both sides of an opening of the manuscript: the upper part was written at the top of the left-hand page (the verso page), while the remaining parts were displayed on the lower staves of the verso and on the facing recto (the right-hand page of the opening), not always in the same order.[20] ( » Abb. Salve regina Ar. fer.)

At least in theory, then, all of the singers could read their respective parts from the manuscript at the same time. Yet the small format of this and many similar manuscripts, the relatively closely spaced notation and the number of uncorrected errors make this seem unlikely; we should more probably regard them as informal copies from which instructors would teach and singers would learn individual pieces that could then be performed from memory. This applies especially to a few pieces in the Leopold codex which abandon the custom of displaying the music across openings and would require different performers or groups of performers to read from both sides of the page at the same time![21]

The scribal work in the Leopold codex (both musical and non-musical) is perhaps best described as informal and functional, rather than formal and decorative. Many of its features are shared with other musical sources of the period, not least the considerable level of inconsistency in presentational details.[22] For example, the upper vocal part is frequently the only one to carry full textual underlay, indicating (if only approximately) which words should be sung to which music. Lower parts are typically provided only with the name of the part (altus, tenor, contratenor, bassus, etc.) and a text incipit, so that singers are left to work out for themselves the details of what text to sing where; in fact these parts may sometimes have been performed instrumentally (» Kap. Aspects of text and performance).

The scribes often left a space at the beginning of each new voice part, into which a decorative form of the first letter of the underlaid text (or, in the lower parts, more usually the first letter of the voice name) might later be inserted. Occasionally such spaces were already left when ruling the staves in advance. Sometimes those spaces turned out to be in the right places when it came to copying the music; sometimes they did not. When no such spaces were left by the stave-ruler, the beginning of the musical notation may have been indented, to leave space for the decorated first letter. Decorative (calligraphic) initials are relatively simple in this manuscript; as in other informal music manuscripts of the period, frequently they were simply omitted.

Some preferences of form and genre in the Leopold codex

An often-discussed feature of the Leopold repertory are two motet cycles performable as substitutes for Mass sections, in the manner of the so-called ‘motetti missales’ of the Milanese court.[23] Gaude flore virginali (no. 31) is a cycle of seven motets replacing the Mass Ordinary on the feast of the Assumption of Mary (15 August); Natus sapientia (no. 32) is a cycle of eight motets for Good Friday. The text of the latter is a variant of Patris sapientia, veritas divina, a rhymed prayer for the Hours of the Passion which was well known in the region (» B. Kap. Patris sapientia); but its traditional melody is not used here. The Missa Paschalis (no. 91) comprises Kyrie, Gloria and Sanctus, as well as introit Resurrexi, motet Christus surrexit and antiphon Regina celi letare, for Easter Sunday. Another Missa Paschalis (no. 113) offers as many as nine sections: antiphon Regina celi, introit Resurrexi, Kyrie, Gloria, alleluia Pascha nostrum, sequence Victimae paschali, Credo, Sanctus and communion Pascha nostrum. This plenary cycle for Easter is followed by Proper cycles nos. 114-116 for Ascension, Pentecost and Corpus Christi respectively. A Missa [de Apostolis] consists of introit, Kyrie and Gloria only (no. 111 = 151). Many of the Mass Proper settings, antiphons and hymns use their own plainsongs, whether as structural tenors or ornamented in an upper voice.

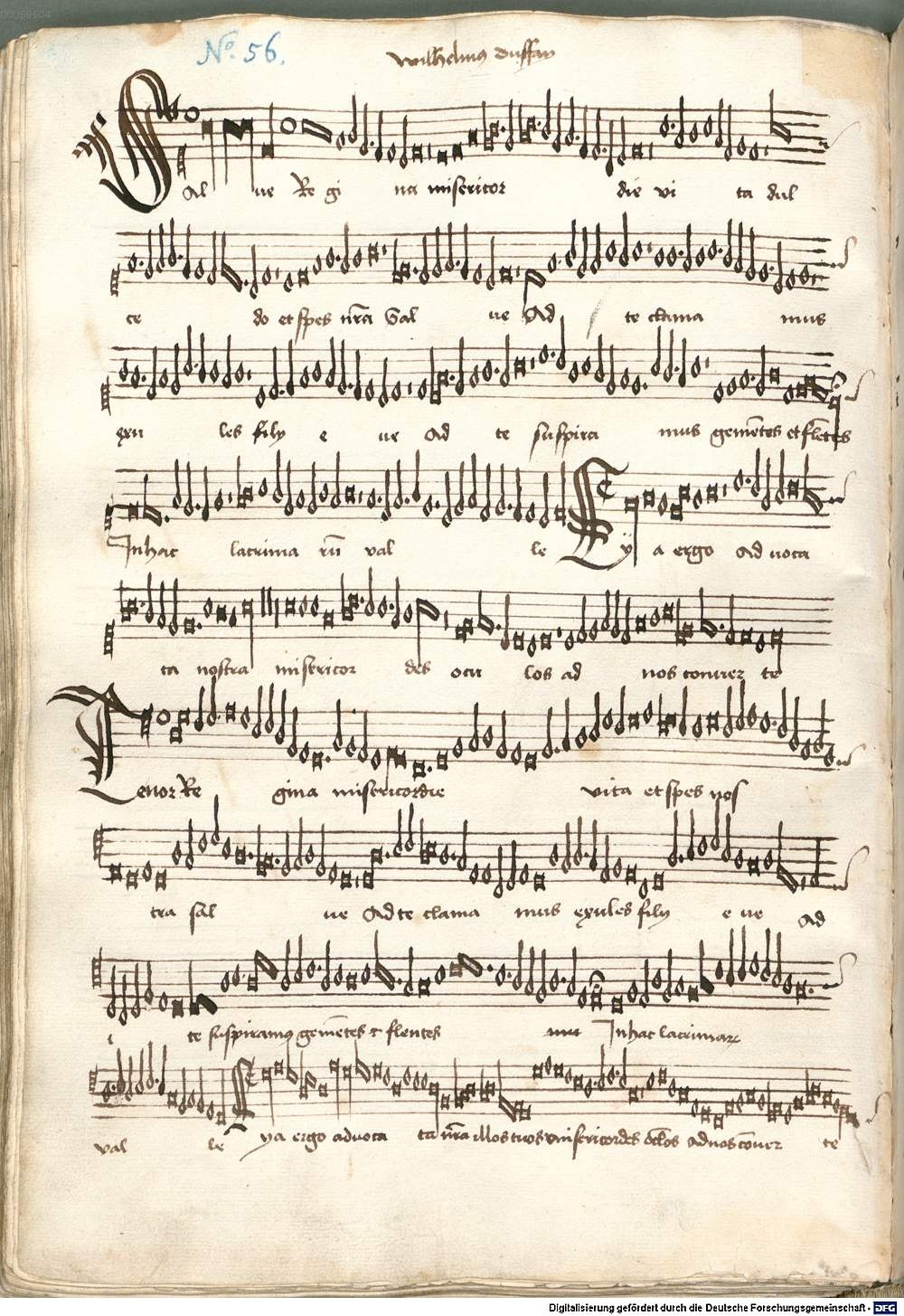

The cantus firmi of Mass Ordinary cycles are more often borrowed sacred and secular melodies. French and Italian songs appear in cycles by Obrecht, Josquin and Compère, German songs in the anonymous Missa Ein Maid zu dem Brunnen (no. 143) and Isaac’s six-voice Missa Wol auff gesell von hinnen, which is notated twice (nos 94 and 172). See » Abb. Missa Wol auff gesell, von hinnen.

Independent settings of German secular songs are of two kinds. Nos 50 and 144 are rustic parodies; five other songs seem to form a cycle (in gathering 6) and were presumably composed locally.[24] The melodies of two of these (nos 36 and 38) are found in concordant sources; Tannhauser ir seid mir lieb (no. 38) also serves as countermelody to the hymn Veni creator spiritus, no. 82.[25]

Characteristic of the repertory are combinatory works, which associate sacred or more often secular songs with a liturgical genre, for example with a hymn (Jesu corona/Ein frischen buelen no. 87, Veni creator/Tannhauser ir seid mir lieb no. 82, Jesu fili patris/O Venus kraft no. 98) or with an antiphon (Ave mundi spes Maria/Gottes namen, no. 25). The sequence Alma chorus domini (no. 45) is composed over the (unidentified) hymn Ehre sei dir, Christe/O du armer Judas, which played a role in the Holy Week rituals of regional churches.[26] A number of works use multiple cantus firmi or quotations: the Salve regina by ‘Ar. fer.’ (no. 64) is overlaid in the top voice with four German and two French songs (see » Abb. Salve regina Ar. fer.); Isaac’s Credo (no. 95) quotes six plainsongs for Corpus Christi and perhaps Palm Sunday;[27] the Missa O Österreich (no. 97) is replete with short plainsong quotes, related to wartime topics.[28] Obrecht’s Missa Plurimorum carminum II (no. 104) exhibits one secular song model per section.

A different type of ‘composite work’ occurs apparently only once: the Mass Proper cycle for Corpus Christi (no. 116) is patched together from compositions by Isaac, Heinrich Finck and a ‘W. Raber’, who may well be the artist and play director at Bolzano, Vigil Raber (» H. Kap. Der Theaterliebhaber Vigil Raber).

Liturgical feasts dominating this repertory are Easter, Corpus Christi and the Assumption of Mary (15 August); the last-named was the patronal feast of the most important brotherhood of priests and citizens at St Jacob’s church.[29] Performances during the visit of Maximilian’s son Philip the Fair in 1503 included a solemn Mass of the Assumption (» I. Kap. Church music at St Jacob’s).

Several anonymous compositions seem to mimic more famous works by re-using their cantus firmi: there are, for example, a Missa [Une mousse de Biscaye] (no. 110, neither Isaac’s nor Josquin’s cycle), a Missa [Petite camusette] (no. 112, not Marbriano de Orto’s) and a Missa [Maria zart] (no. 117, not Obrecht’s). The two ‘motetti missales’ cycles (nos 31 and 32) may imitate the Milanese style of that name. Yet in some of these cases the Leopold work could have originated even earlier. The anonymous Missa [Maria zart][30] deserves attention for its cantus firmus treatment and rhythmic style – the beginnings of Gloria and Credo seem to echo Isaac’s motet La la hö hö.

Aspects of text and performance

The French language is virtually avoided in the Leopold codex. Only four French text incipits occur, indicating borrowed melodies. 21 pieces entirely lack text and title; for a few others the omitted text can be inferred (no. 33, De tous biens) or a cantus firmus remains unidentified (the large bipartite motet ‘P’, no. 56). Many other items, particularly in the second section, have extremely little underlaid text, not only in the lower voice-parts and for Mass Ordinary sections or antiphons whose words are well-known, but also for motets such as O propugnator miserorum (no. 80), the second part of which is notated entirely without words; no other source of this specially written text is known today. The majority of the insufficiently texted compositions are motet-like in form, not secular songs whose words might have been familiar.

The avoidance of French songs contrasts with the repertory of the ‘Linz fragments’ (A-LIb Ms. 529), which, despite being a much smaller, incomplete source, contain eight of them. It is tempting to conclude that the Linz fragments came from a courtly manuscript, used partly by foreign musicians, whereas the Leopold codex served a school environment. Textless pieces, however, are found in both these sources, raising the question whether they were used by instrumentalists.[31] The musical establishments of Archduke Siegmund and King Maximilian had ample use for skilled instrumentalists.[32] Performative collaboration between singers, trombonists and cornettists (musica alta) is documented, for example, in descriptions of the Innsbruck liturgical services of 1503 (» I. Kap. Church music at St Jacob’s). In secular surroundings, players of soft instruments would serve together with solo singers at any time, using secular, sacred and motet-like pieces alike.

It remains to be considered whether textless pieces or voice-parts might have been vocalised or even sung with words after rehearsal under the instructions of a teacher or cantor. That some expert knowledge needed to be applied before the notated music could be performed seems borne out also by some cases of a singular textual adaptation or rewriting. The unique variant ‘Natus sapientia’ of the well-known prayer text ‘Patris sapientia’ may be such a case. Isaac’s motet Argentum et aurum is structurally built upon a single text sentence, whose liturgical melody is repeated throughout the work. The Leopold scribe, however, added an extra responsory text which fits the feast (of St Peter and Paul), but its plainsong is absent from the layout of the music: a secular composition was transformed here into a liturgical motet.[33]

Watermark dating in the Leopold codex

The editor of D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, Thomas Noblitt, has proposed a framework for the watermark (WM) dating of all the gatherings in the manuscript, identifying most of its watermarks (on the basis of watermark drawings by Gerhard Piccard and additional research) and applying these findings to its composite structure.[34] According to Noblitt’s sequence of paper dates, the first section of the codex was compiled between c.1466 and c.1485, and the second, more composite, section between c.1487 and c.1511. (See » Abb. Synopsis.)

While paper dates should not be confused with actual dates of copying, Piccard’s life-long watermark research has demonstrated that, in this period, paper was usually inscribed within a three-year frame of its manufacture. Of course, there can be exceptions. But the Leopold codex with its 45 different watermarks distributed over 48 gatherings enabled Noblitt to situate many gatherings within sequences of dates, where the order of compilation shadows the chronology of the manufacture of the paper – allowing for the conclusion that the inscription took place within the time-frames outlined by the paper dates. If a batch of different papers was stored unused for a long time, it was likely that they were inscribed in a different order from that of their manufacture, since copyists were not concerned with the watermark dates of their papers. If, however, two or more different papers were inscribed in the same order in which they had originally been manufactured, this probably happened within the three-year framework of their origin – that is to say, the papers were inscribed one by one as they were being acquired. This evidence was the more compelling the more different papers were found to be inscribed in the chronological order of their manufacture: every batch of paper would then serve as terminus ante quem for the inscription of the preceding one.[35]

The order of the compositions in the Leopold codex, however, does not always follow the chronology of the watermark dates. This is unproblematic in the second section, whose separate gatherings (or groups of gatherings) were in any case arranged in a more arbitrary order after they had all been collected. The first section, however, was mainly created by a single scribe (‘A’), who could in his copying have shadowed the watermark chronology as successive papers became available. Instead, his progress from a group of papers datable c.1466-72 (gatherings 1-4, WM 1-5), to a group of c.1474-77 (gatherings 5-9, WM 6-8),[36] and finally to one of c.1480-85 (gatherings 10-13, WM 10-15) is upset by the re-appearance of older paper (WM 6: 1476) in gatherings 14-17 (» Abb. Synopsis).[37]

Josquin’s and Isaac’s ‘1476’ compositions

A few of Noblitt’s copying dates in the Leopold codex conflicted with the prevailing historiography of the music. As it happens, some of this music was copied on papers (WM 6 and 16/17) which deviate in the codex from the chronology of the paper manufacture (see gatherings 14-17 in » Abb. Synopsis).

Josquin researchers could not believe that his Ave Maria…virgo serena (no. 79, gathering 15) might have been copied as early as c.1476: the work was formerly thought to date from the 1490s, while more recently it has been assumed to be from the 1480s and in a ‘Milanese’ motet style – yet the composer is not documented in Milan before 1484. Joshua Rifkin has painstakingly analysed the handwriting chronology, arriving at the solution that the copy of Josquin’s motet was an addition of the 1480s, by which time scribe ‘A’ had reverted to an earlier form of his custos.[38]

Nevertheless, a copying date in the 1480s could even be defended for the entire sequence of gatherings 14-17: although these gatherings consist of older paper (WM 6 and 16/17), they are placed outside the ‘correct’ chronology of paper dates here, so that the possibility of their having been inscribed some eight years after manufacture cannot be dismissed. Gathering 17 is followed in the codex by a unit of a much later date (gathering 18, WM 18: 1506-07), arbitrarily inserted here at the end of the first section of the codex (» Kap. Genres and composers), and following this, the second section of the codex begins on papers datable 1487-88: thus gatherings 14-17 lack a terminus ante quem which would fix their copying date before c.1487. If the entire gathering sequence 14-17 remained unused paper until the early 1480s, Rifkin’s handwriting chronology would not even be necessary to defend a copying date of c.1484 for Josquin’s motet. It seems more likely, however, that gatherings 14-17 were indeed inscribed in c.1476-78 but inserted in the codex later, placed outside the chronology of the paper dates,[39] and that Ave Maria…virgo serena (no. 79) and O propugnator miserorum (no. 80) were then added on empty pages in the 1480s.

A different argument applies to three motets by Henricus Isaac which occupy the end of gathering 7 (WM 6: 1476), within the ‘correct’ order of the paper dates. The third motet, Inviolata integra, is incomplete at the end, as a subsequent gathering is lost. More music by Isaac may have followed at this point. Gathering 8 is a late insertion; thus the terminus ante quem for the Isaac motets is gathering 9, mainly consisting of the same 1476 paper as gathering 7.

It so happens that the earliest known document for Isaac’s biography concerns his presence at Innsbruck in September 1484,[40] when he was paid for services rendered as ‘componist’ to the Tyrolean court (probably at least during Archduke Siegmund’s wedding in February of that year).[41] Unless we hypothesise that scribe ‘A’ added the three Isaac motets (and possibly more music by him in the next gathering) all as late additions within the original sequence of the manuscript,[42] the date of c.1476 for these copies should be maintained. Thus Isaac’s motets reached Innsbruck well before the composer himself in 1484, whether during an earlier visit or through copies coming from elsewhere, perhaps through a patron linked to the compilers of the codex.[43]

Concordances

Much of the music in the Leopold codex is linked to musical repertories of other European centres, where the same compositions were also known and copied.[44] The way in which these concordances are distributed over the existing sources from this period has bearings on date and provenance of the compositions, on musical-cultural transfer processes and even on political affiliations between institutions. The direction in which a transfer took place can normally be inferred from the dates of the concordant copies (if known); but often there must have been common exemplars that are now lost. It is also worth knowing whether transfers concerned individual compositions or entire collections or gatherings, and whether pieces are shared with only one other source or with many.

The series of concordances begins with a special case. The Strahov codex (» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47), which was compiled in c.1467-70 for a catholic church in Bohemia, probably the cathedral of Prague,[45] shares six compositions with the Leopold codex, one of which (Kyrie de BMV, no. 11) is known only from these two manuscripts. But all six pieces, which are dispersed over the entire large Strahov codex, occur close together as nos 7, 8, 10, 11 and 14 in Leopold.[46] They are copied here in gatherings 1 and 2, datable c.1466-69, contemporaneously with the creation of Strahov. (More concordances may have existed on the lost first 19 folios of Leopold.) Although shared links with a Habsburg court repertory are possible, a musical transfer between church schools seems the more likely reason, happening in this case before the later gatherings of Leopold were written.

Gatherings 1-5, datable before c.1472, also transmit 13 of the altogether 15 compositions shared with the Trent Codices (I-TRbc 87, 88, 89, 90 and 91, I-TRcap 93*), another cathedral repertory.[47] Codex I-TRbc 89 (datable c.1462-68) is most closely related with six concordant pieces. It uniquely shares with Leopold the extraordinary eight-voice motet Ave mundi/Gottes namen (no. 25), a local composition imitating the style of Antoine Busnoys.[48] A famous work found only in Leopold and codex Trent 91 (c.1472-77) is the motet In hydraulis by Busnoys (no. 24), composed in homage to Jean Ockeghem between 1465 and 1467.

The Leopold codex is the earlier source in all its concordances with other manuscripts. Most of them occur, after c.1490, in collections from Saxony: ten in the ‘Apel codex’ from Leipzig (D-LEu Ms. 1494), six in the Saxon collection D-B Mus. Ms. 40021 (which also shares a scribal hand on its fols 253r–254v), and altogether ten in the even later choirbooks from Annaberg (Saxony), D-Dl Ms. Mus. 1/D/505 and 1/D/506. Six works are also found in the Czech Speciálník codex (CZ-HKm Ms. II A 7),[49] which shares material with Saxon manuscripts. The concordant compositions are mostly of Netherlands origin, thus they apparently travelled first to Innsbruck and then to Saxony, through affiliations brought about by Archduke Siegmund’s wedding to Katharina of Saxony in 1484, and by King Maximilian’s political alliance with the Saxon court at Dresden and Torgau, members of which visited Tyrol in 1496-97. Similar clusters of concordances connect the Leopold codex with the court repertory of Milan (four concordances in the ‘Gaffurius codices’ I-Md 2269, 2267 and 2266) and Ferrara (I-MOe Ms. α. M. 1.2: three Mass cycles by Josquin and Obrecht). The seven works attributed to Johannes Martini in the Leopold codex may also have come from Ferrara, where Martini was court composer 1473-1497, although they are spread over various Italian manuscripts. Martini was acquainted with Paul Hofhaimer and Isaac; he probably visited Innsbruck around 1466 and 1473. The ducal courts of Milan and Ferrara were politically allied with the Habsburgs: Ferrara with Archduke Siegmund, and Milan with both him and his successor Maximilian, who married Princess Bianca Maria Sforza of Milan in 1493.

Concordances with all other manuscripts, mostly in Italy and Germany, are limited to two or three works in each case, copied after the Leopold entries. It is striking that the Linz fragments (» K. Die Linzer Fragmente), which seem to have originated in the Habsburg orbit in c.1490-92, duplicate only two widely disseminated works from Leopold (nos 52 and 150).

Institutions, scribes and patrons

The conclusion that the institutional background for the Leopold codex is likely to have been the parish church of St Jacob at Innsbruck may be reached in various ways. One of these is that Nicolaus Leopold, schoolmaster in 1511, may have inherited all this music from his predecessors at St Jacob’s. Admittedly, the political and cultural affiliations of the repertory, which are reflected in the musical concordances, point to a Habsburgian courtly background – which is why the manuscript has often been associated with a Habsburg court repertory or even with ‘the Imperial court’.[50] But the Leopold codex has, to start with, no known connections with the court music of Emperor Friedrich III, who resided at Graz and later at Linz, where he died in 1493.[51] The entire first section originated before c.1490, when Innsbruck was the residence of Archduke Siegmund, Count of Tyrol. During this period, Siegmund used the church of St Jacob, on his doorstep, for ceremonial sacred services, with music provided by the schoolmaster and his choirboys, occasionally together with singing chaplains (cantors) in his employ.[52] The court organists – Nicolaus Krombsdorfer from 1463, Paul Hofhaimer from 1478 – doubled as church organists. The prince paid individual musicians, including many visitors, and sponsored secular music – but the official liturgical repertory must have been recorded at the church itself. Scribe ‘A’, who copied most of the sacred music in the first section of the codex, is to be sought among the musicians of the church and the court. The leading musician was the cantor and organist Krombsdorfer, who in his later years was court chaplain, and ultimately parish priest of St Jacob’s, although precisely because of his many functions and high-ranking position he seems less likely to have acted as a humble music scribe.[53] This activity rather befitted the schoolmaster himself, who in 1466-1478 was Wolfgang Unterstetter. His successor (or deputy) in 1478-1486 was Matthias Sekeresch, but in 1485 Unterstetter received a pension because of illness, implying that he had been serving in some capacity in the intervening years.[54] Thus we may tentatively propose the identification of Unterstetter with scribe ‘A’, whose work on the codex in fact ceases in c.1482-85.

What appears to be a scribe’s name – ‘Quest’ (or Huest) ‘Frölich’ – is recorded in the manuscript itself on fol. 195r. The scribal hand (‘J’) associated with this signature (if that’s what it is) appears only in gatherings 19 and 20 (c. 1487), in a copy of Isaac’s Missa Wol auff gesell. The following 28 gatherings were compiled by altogether 31 scribes who supplied individual gatherings or sequences of gatherings dedicated to single larger works, often with smaller additions. These gatherings, which were originally kept unbound, are not consistently arranged in chronological order.[55] They seem to have been acquired from individuals outside the main establishment who came and went. In this way, the repertory may reflect the varied musical life of the courtly and commercial city as well as the regular liturgical needs of its main church. In the early 1490s, scribal activity focuses on new works by Jacob Obrecht (gatherings 22, 24 and 25), which may well have been imported by musicians of King Maximilian who then partly resided at Innsbruck.

After 1492, however, Innsbruck was no longer the main residence of a Habsburg prince. The king was more often in Augsburg or on campaigns further afield. His marriage to Bianca Maria Sforza (1493, celebrated in Hall, 1494)[56] had the effect of keeping at least one royal figure in or near Innsbruck, where her husband sometimes left her behind; she and Siegmund’s wife Katharina of Saxony (until 1496) used the Hofburg and various castles in Tyrol, probably frequenting St Jacob’s for ceremonies.

Most importantly, the repertory which research has associated with Maximilian’s chapel(s) after 1492 is conspicuously absent from Leopold. There is no new work by Isaac, who in 1496 was (re-?)engaged by Maximilian in Italy and was soon to compose sumptuous service music for him. Concordances with typical sources of the royal household repertory are strikingly rare. Not a single composition in the codex is attributable to Paul Hofhaimer, who in 1489 joined Maximilian’s service, or to Pierre de la Rue, who in 1503 visited Innsbruck and Hall with his employer, Philip the Fair, or to younger musicians of Maximilian’s entourage such as Adam Rener.

This is not to say that Habsburgian links are absent. The penultimate composition to be entered (no. 173: 1509-11) is the anonymous five-voice motet Ave mundi spes Maria, dedicated to Maximilian’s councillor Matthäus Lang, then Bishop of Gurk. But the Leopold repertory in its later years has no consistent connection with a Habsburg chapel. The schoolmasters acquired what they could, and probably instigated some new compositions to cover ceremonial needs. New research may explore the possible patronage of the princesses, the music-loving Katharina of Saxony, and the oft-forgotten Bianca Maria Sforza, in shaping the musical heritage of the Leopold codex.

[1] Colour images of the manuscript are available at https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/.

[2] Some 34 hands can be distinguished in the second section of the manuscript alone; one of these (hand ‘Y’, fols 370r– 379v) also occurs in the manuscript D-B Mus. Ms. 40021 (fols 253r–254v).

[3] Noblitt 1987-96, I, viii; synopsis of foliations in IV, 313-14.

[5] Noblitt 1968, 1974, 1987, 1997 (etc.). For other recent research, see Strohm 1993, 516-23; Rifkin 2003, Rumbold 2018.

[6] See, for example, Josquin Desprez, Missa Fortuna desperata (fols 172r-178r), recorded in 2001 by the Clerks’ Group, dir. Edward Wickham (ASV label, catalogue no. GAU 220); in 2009 by the Tallis Scholars, dir. Peter Phillips (Gimell label, catalogue no. 42); and in 2018 by Biscantor! Métamorphoses (Ar-Re-Se label, catalogue no. AR 20181). The second Agnus Dei of Isaac’s Missa Wol auff gesell/Comment peult avoir joye (fols 179r-196r and 456v-463v) was recorded by Capella Alamire and the Alamire Consort, dir. Peter Urqhuart, CD Music of Pierrequin de Thérache (Centaur label, catalogue no. CRC3282), track 10. Kyrie of the anonymous Missa O Österreich (fols 205v-213r): Ensemble Rosarum Flores, CD Global Player Maximilian: Musikalisches Networking um 1500 (Musikmuseum label, catalogue no. 13042), track 1. Obrecht’s Missa Si dedero (fols 449v-456r): ANS Chorus, dir. János Bali (Hungaroton label, catalogue no. HCD 31946). The anonymous motets Ave mundi spes/Gottes namen (fols 29v-30r) and O propugnator miserorum (fols 148v-150r): Stimmwerck, SACD Flos virginum: Motets of the 15th Century (CPO label, catalogue no. 7779372), tracks 8 and 6, respectively. Isaac’s motet Argentum et aurum (fols 72v-73r) and the German songs So stee ich hie auff diser erd, Ich sachs ains mals, Gespile, liebe gespile gut, Es sassen höld in ainer stuben (fols 51v-53r): Ensemble Leones, CD Argentum et aurum: Musical Treasures from the Early Habsburg Renaissance (Naxos label, catalogue no. 8.573346), tracks 1, 16, 22, 20 and 21, respectively.

[7] It is not to be confused with the Hofkirche, adjacent to the Hofburg, which was completed in 1553 and contains Maximilian’s cenotaph.

[8] » I. Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck (Helen Coffey).

[9] Fässler 1975.

[10] Fässler 1975, 32, from Tiroler Landesarchiv (TLA) Innsbruck, Raitbücher der tirolischen Kammer, 1511, vol 56, fol 77v, vol 56, fol 290v.

[12] The city archives of Innsbruck (Stadtarchiv, Register, p. 43), mention a ‘Veit schulmaister’ in 1498.

[16] Dèzes 1927; see also Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 369.

[17] The work is later anonymously transmitted in Librone 1 of the Gaffurius-Codices of Milan (I-MD 2269). Rifkin 2003, 255, thinks that it might be by Antoine Busnoys.

[18] Rumbold 2018, 319-22 describes the copy of the Sanctus and Agnus Dei in detail, with facsimile.

[19] For the distribution of the music in the manuscript see Rumbold 2018, with a full inventory.

[20] For details, see Rumbold 2018.

[21] No. 55, for example, is a textless piece written on the two inner sides of a bifolio (fol. 75/84), which was then wrapped round an existing gathering (8), so that the two sides could no longer be read simultaneously. See Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 344, where the last sentence must read ‘so daß eine Aufführung aus dem Ms. unwahrscheinlich ist’.

[23] Noblitt 1968, Rifkin 2003. The actual ‘motetti missales’ of Milan (1470s and later) are not copied here.

[24] » Hörbsp. ♫ for all five songs.

[25] ‘Tannhauser, ihr seid mir lieb’ (Venus addressing Tannhäuser) is a stanza of the ‘Tannhäuserlied’ (Nun will ich aber heben an), printed in Nuremberg, 1515; the Leopold codex is its earliest known source.

[26] See » A. Kap. Der Prozessionshymnus (Stefan Engels): » J. Kap. Passions- und Osterfeierlichkeiten (Andrea Horz); » Notenbsp. O du armer Judas.

[27] On this work, see Staehelin 1977, 148-50, 205.

[28] Noblitt 1992 calls this a Missa in tempore belli; see also » D. SL O Österreich. Page layout of the Agnus Dei described in Rumbold 2018, 322-23.

[29] Steinegger 1954. Further on traditions of the church, see » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck.

[30] Page layout described in Rumbold 2018, 329-34.

[32] » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; » I. Instrumentalkünstler (Martin Kirnbauer).

[34] See Noblitt 1974 (with table of watermarks, p. 39); Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 315-40.

[35] On the methodology, see also Strohm 1983, Rifkin 2003. Watermark dating along these lines has also been applied to the Trent codices (» K. Kap. Die Datierung) and the St Emmeram codex (Strohm 1983, Rumbold-Wright 2006, 14-19).

[36] WM 4, 9 and 10 deviate from the chronology, but these papers are only individual bifolios (26-27, 75/84, 85/98), added to already existing gatherings. Gathering 8 randomly assembles papers datable between 1477 and 1482, but it was not originally meant to be arranged in this order nor perhaps to be placed here: see Noblitt 1974, 42-43.

[37] On gatherings 14-17 (WM 6 with embedded papers WM 16/17, 1476-78), see Noblitt 1974, 41.

[38] Rifkin 2003, 285-6 and 300-1. Ave Maria…virgo serena is placed near the end of gathering 15 (WM 17: 1476-78); it is followed there only by an even later addition (in a different hand), the anonymous motet O propugnator miserorum, addressing Margrave Leopold III of Austria (canonised 1485), on which see » F. SL Die Motette O propugnator miserorum. The position of the motet in Josquin’s oeuvre and the possibility of its having been written outside Milan is discussed in Fallows 2009, 60-61 and 118-19.

[39] Thus Noblitt 1974, 45.

[40] Staehelin 1977, II, 19.

[41] See » I. Kap. Three early motets (David Burn), and Strohm 1997.

[42] For Rifkin 2003, 300 and 301 n. 124, these copies belong to a later stage of the main scribal hand, but the paleographical evidence seems overstated.

[43] Strohm 1997 suggests that Isaac did have contact with ‘Germanic’ idioms as they appear in these works before 1484, but that he also disseminated these idioms to other central European musicians.

[44] See the concordance table in Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 308-11.

[45] » F. Kap. The Strahov codex (Lenka Hlávková).

[46] See the description in Gancarczyk 2011.

[47] The concordances with Strahov and Trent 90 include, predictably, some of the oldest music in Leopold, for example the English motet Anima mea liquefacta est (no. 2), doubtfully ascribed in modern research to John Forest, and the Agnus dei secundum of the Mass cycle by Jean Pullois (no. 7), both composed before 1450.

[48] » J. SL In gottes namen faren wir; » Hörbsp. ♫ Ave mundi spes/Gottes namen. On both works, see also Strohm 1993, 532-3.

[49] » F. Kap. The Speciálník codex (Lenka Hlávková).

[50] There was no Holy Roman Emperor in 1493-1508.

[51] See » D. Hofmusik. Albrecht II und Friedrich III. The composer abbreviation ‘Ar. fer.’ on no. 64 (gathering 11: 1483-84) could refer to Emperor Friedrich’s chaplain Arnold Fleron: it so happens that an ‘Arnold’, probably Fleron, is recorded at Innsbruck as ‘componist’ in both 1483 and 1484: see Strohm 1993, 518 and 531 n. 478

[52] Further on the organisation of the courtly music, see » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; Senn 1954.

[53] Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103, rejects the identification of scribe ‘A’ with Krombsdorfer because of the ‘Italianate’ features of a letter he sent in 1472 to Duke Ercole d’Este (» G. Kap. Ferrara): but this calligraphy was surely chosen for the benefit of the addressee.

[54] Wolfgang Unterstetter, suffering from podagra, received from the court a weekly measure of salt: HHSt Wien (A-Whh), Kopialbuch H. Nr. 7, 1485, fol. 170v-171r.

[55] See » Abb. Synopsis, and Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 341-57; Rumbold 2018, 287-89.

[56] » I. Music and Ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck (Helen Coffey)

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Ian Rumbold and Reinhard Strohm: “The Codex of Magister Nicolaus Leopold”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/codex-magister-nicolaus-leopold-0> (2021).

![Abb. Missa Wol auff gesell, von hinnen [Comment peut avoir joie], Henricus Isaac. Abb. Missa Wol auff gesell, von hinnen [Comment peut avoir joie], Henricus Isaac.](https://musical-life.net/files/styles/embedded/public/f._195r.jpg?itok=3Dx6S1HD)