Music in the church service: Vienna

Church plainsong and “music”

Music and liturgy stood in a different relationship to one another in the Middle Ages than they do today. Although Latin plainsong, when sung within the liturgical rite, exhibited a recognisable musical component, this was clearly subordinate to the delivery of the words. Today, we usually understand “music in the liturgy” as an autonomous activity, such as the performance of composed works—often also instrumental—or the rehearsed singing of the church choir. Similar added music also existed in the late Middle Ages – but with the difference that it was usually related to traditional chant and legitimised by it. What follows will focus particularly on those performances that stood out from plainsong due to a more striking or intense musicality, and on certain musical aspects of plainsong performance itself. The terminology used in the documents under examination, however, obscures the distinction between plainsong and “music”. The expression “sung Mass” (“Ambt”) did not usually refer to the musical genre of the composed Mass Ordinary cycle, but rather to the service as a whole, whether or not it included polyphonic singing; likewise, a polyphonic setting of the Salve Regina was not referred to as a “motet”, but simply as (a) Salve Regina.

“Church services” were not only the fundamental performances of the Opus Dei, namely the Mass and the Divine Office, but also other actions such as church processions, consecrations and blessings, services for weddings, baptisms and funerals. Liturgical activity required authorisation by church authorities (this included the approval of indulgences, feast days and new devotions), the appointment of priests, the preparation of altars, relics (“Heiltümer”), liturgical vessels and vestments, bell-ringing and the employment of altar servers (“Leviten”) and sacristans. In addition, organists, cantors and choirboys were involved when a more musically elaborate arrangement was intended. While priests’ salaries were almost always secured through ecclesiastical benefices funded by pious endowments, the church usually had to pay other participants from its current income, which itself largely relied on endowments and donations. The accounts of the Viennese churchwardens (lay administrators), for example of St Stephen’s or St Michael’s, record such expenditures, with large sums also noted for chrism oil, sacramental wine (“Opferwein”), and especially candles (“Steckkerzen”).

Personnel requirements for church music

In Viennese churches and monasteries,[1] the musical embellishment of sacred services was already popular in the fourteenth century and developed rapidly. Crucial to this were the roles of the cantor, the organist and the schoolmaster. At St Stephen’s, a cantor is mentioned as early as 1267, a century before its elevation to a collegiate church in 1365.[2] The first mention of organ playing on 15 June 1334 (for the Feast of Corpus Christi, based on an endowment by the parish priest Heinrich von Luzern) appears quite late compared to what was probably the first use of the organ:[3] “cantantibus in organis et famulis folles calcantibus xxxvi denarios” (to the organ players and their assistants who operate the bellows, 36 pfennigs).[4] Between 1370 and about 1391, there was an organist at St Stephen’s by the name of Master Peter.[5]

In the oldest surviving church accounts of the parish church of St Michael from 1433, an organist (not named) is also mentioned. At that time, St Michael’s already had two organs, a large one and a small one, which was accessible from the rood screen.[6] One of the organs was “gebessert” (repaired) in 1437 and received a grille in 1444. In 1450, Master Andre, organ master of Stein, was paid 24 tl. for tuning and a repair of the large organ; the total repair costs that year amounted to over 66 lb (Churchwarden’s Account 1450, p. 19). Further repairs are recorded for 1460, 1472, 1480 and 1498; in 1474, the painter Hans Kaschauer carried out decorative painting on the organ.[7] The role of cantor at St Michael’s in 1433 was still combined with that of the schoolmaster in a single person.[8] Whether the cantor and schoolmaster could be paid at all, or whether these were one or two separate positions, depended in fact on local circumstances. The embellishment of the liturgy with singing – in addition to the chant performed by the priests – was primarily the task of pupils, who sang under the direction of their teacher. If a school was large enough, Latin instruction and singing lessons could be divided between two instructors – possibly with specialised vocal training for particularly gifted pupils.

In the late Middle Ages, Vienna had four Latin schools administered by the city council: at St Stephen’s (the “Bürgerschule”, “civic school”, which was superior to the other three), at the Schottenkloster, at St Michael’s (attested since 1352), and at the Bürgerspital, “civic hospital” (since 1384).[9] That secular pupils (scolares saeculares) were also educated at the Schottenkloster is evident from a reform ordinance of 1431, which forbade them to participate in the choral prayer and ordered their instruction to take place outside the monastery buildings.[10] The opposite must therefore have been the practice previously. Already on 5 February 1310, the participation of monastery pupils in the vigil (Matins) of a memorial foundation was prescribed, and their education had to take this into account. The participation of pupils in the vigil was confirmed in 1330.[11] During the tenure of the last Scottish abbot, Thomas (1403–1418), a “music school with its own choirmaster” is said to have been established; in 1413, a “singing fellow” from Pulkau is mentioned.[12] In 1418, the new abbot, Nicolaus von Respitz, was solemnly installed by the visitors, with the participation of the school rector, the “succentor” or “Junkmaister” (see also » E. Ch. Junkmeister, Astanten), i.e. assistant to the school cantor, who elsewhere was also called subcantor or Junger (cf. Ch. Hermann Edlerawer and the building of the Cantorey), and the pupils.[13] Evidence for the participation of pupils in liturgical services – mostly funded by pious endowments – also exists for the private “Otto and Haimsche” Town Hall Chapel. After it was rebuilt under chaplain Jacob (der) Poll in 1360–1361, endowments from the years 1367–1373 obliged four poor pupils who wished to become priests to sing in the chapel.[14] At the Peterskapelle, there were scholarships in 1412 and 1420 for four poor pupils who were to assist with the singing.[15] The chaplain was to say daily Mass, but also required “vier Schüler […], die zu singen helffen waz zu singen not ist in derselben sand Peters capelln” (four pupils who help with the singing of whatever needs to be sung in the said St Peter’s Chapel).[16] Apparently, no other priests were available to form the choir for these Masses. The pupils also had to read the Psalter during the vigils; each was to receive 1 tl. annually – a considerable income.[17] At the private Philipp and Jakob Chapel in the Kölnerhof (Klosterneuburgerhof), four pupils were also to read the Psalter during Easter Week, according to a 1395 endowment.

The first documented reference to the schoolmaster of the St Stephen’s school dates from 1237, thirty years before the first mention of the cantor, whose position was apparently split away from the schoolmaster’s role.[18] Since the founding of the collegiate chapter at St Stephen’s by Duke Rudolf IV (confirmed in 1365), the cantor of St Stephen’s (the “Sangherr”) was a leading member of the chapter (canonicus). This is to be distinguished from the role of the cantor of the civic school, who was subordinate to the schoolmaster and was paid by the city council and through endowments (cf. Ch. Development of the Cantorey (choir school) of St Stephen’s).[19]

The institutional foundation of the chapter of St Stephen

The establishment of the collegiate chapter at St Stephen’s by Duke Rudolf IV was part of a longer effort by the Austrian rulers to ennoble their most important secular church.[20] Already in the fourteenth century, the church was referred to as “der thumb” or “die thumkirchen” (i.e., cathedral); it was not designated as a bishop’s seat until 1469 and was factually established as such only in 1480. The collegiate chapter, dedicated to All Saints and Angels, had already been conceived by Rudolf IV in 1358 and confirmed by Pope Innocent VI. According to many historians, this was originally a foundation for Duke Rudolf’s princely palace chapter and burial place in the Hofburg Chapel, which was transferred to St Stephen’s in 1365.[21] However, Viktor Flieder shows that a chapter never existed in the Hofburg Chapel and that the foundation was intended for St Stephen’s from the outset.[22] The liturgical services of the St Stephen’s chapter are described in a ducal memorial foundation dated 28 March 1363; this formed, based on the Passau diocesan rite, the starting point for the church’s further liturgical and musical development.[23] Here, Duke Rudolf created 25 prebends for canons, one of whom, as provost, held the prepositura. Three other leading offices were the decanatus (dean), the thesauraria (treasurer, sacristan), and the cantoria (cantor, Sangherr). There were also 25 (later 26) prebends for chaplains. The “choirmaster” (magister chori), who is not mentioned in Rudolf’s foundation, was the senior among the priests entrusted with pastoral care (octonarii: the group of eight).[24] His role is clearly distinguishable from that of the cantor.[25]

Duke Rudolf’s regulations for the services at St Stephen’s

The memorial foundation of Rudolf IV from 1363 provides for three daily Masses (“offices”) at the chapter’s main altars: a Marian Mass in the morning at the Marian altar, a High Mass at the Corpus Christi altar above the princely tomb (in the central choir), and the daily Mass at the Fronaltar (high altar).[26] The ceremonies – opening of the altarpiece panels, display of relics, lighting of candles, procession with banners, cross and lanterns, ringing of bells – were differentiated according to the rank of the feast; on the feast days of saints buried in the church, the organ was to be played at Vespers and High Mass, and the “large and small bell” rung. At Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, All Saints, the church’s dedication day and Corpus Christi, more candles were used (24 on the duke’s tomb alone). All relics were to be placed on the altar, and “überall die kirchen zieren mit der schonsten gezierd so si habent” (the whole church decorated with the finest ornaments they have). All the canonical hours (Divine Office) as well as the daily Mass were to be sung “in der Orgel” (with the organ), and all the bells rung “so man schönste mag” (as beautifully as possible) for Mass. On Corpus Christi, all available relics, banners, canopies, 30 candles and 10 lanterns were carried through the city; all parish priests, monks, chaplains, and priests from both the city and the suburbs, including the Knights of St John, the “Holy Ghost” brethren, and the “Spitaler” (hospital clergy), were required to take part in this procession. They were to come to St Stephen’s “mit all irr Schönesten gezierd, die sie habent” (with all their finest ornaments) and join in the procession.[27]

In the “great” foundation charter of 16 March 1365 (to distinguish it from the “small” foundation charter of the same date), the duties and salaries of the officiants, as well as the underlying property rights, are set out in greater detail.[28] The main purpose of the entire foundation remained the commemoration of the dead for the duke and his family. A special benefice served to provide priests with food and drink, “so that they may observe the anniversary of our death”.[29]

In addition, there were dress codes, the designation of the clergy’s positions within the church, and the distribution of Masses among the provost, canons and chaplains. Quantity was of great importance: the dean had to ensure that a total of 51 Masses were sung or said in the church each day, none of which was to be omitted. Most were certainly spoken only. However, there were also regulations concerning singing and the organ. At the end of the canonical hours, which were to be sung “with a clear and high voice”, a Marian antiphon was to be performed “with a bright song”, after Vespers, Matins and None this was to be the Salve Regina. The three daily Masses at the main altars were also to be sung “with a clear and high voice”.[30] The participation of pupils was required for the Masses: 24 of them for the two daily High Masses, and at least 13 for the other High Masses and Vespers. The “masters, students and pupils” were required to take part in the processions of eight major feasts: Christmas, Easter, Pentecost, All Saints, All Souls, the Assumption of Mary, Corpus Christi and the ducal memorial day. Here, “der Schullmeister der grossen Schull mit ganzer Universitaet” (the schoolmaster of the great school with the entire university) had to be present and to assist in the singing and processing).[31] It was important to the founder that everyone took part, including the newly-established university. The participation of university members in the processions was, in a sense, part of the foundation itself (cf. Ch. Church and university).

The duties of the cantor are described in the foundation charter as follows:

“Er soll auch innhaben die Orgell und damit orden[tlichen] göttlichen Dienst zu begehen und achten, dass das Gesang zu göttlichen Dienst ordentlichen, gänzlichen und löblichen vollbracht werde, so man immer pest und schenst mag, wann des unser Erlöser, der allmächtig Gott wohl werth ist, und soll auch die Processe richten und ordnen, dass die allzeit ordentlichen vollbracht werde.” (He shall also be in charge of the organ and thereby conduct proper divine service, and ensure that the singing in divine service is carried out properly, completely and commendably, as best and as beautifully as possible, for our Redeemer, Almighty God, is truly worthy of it. And he shall also direct and organise the processions so that they are always carried out properly.)[32]

In the case of processions, the founder makes a clear distinction between those that remain within the church and those that go “into the city”.Reforming Service Orders at St Stephen’s

A new Latin order of services at St Stephen’s (20 March 1436) was issued by the visitors who, in the course of the Melk Monastic Reform (» A. Melk Reform), also examined the collegiate church.[33] The duties of the provosts, deans, sacristans, and cantors are described here more clearly than in the less systematically formulated German-language foundation charters of Duke Rudolf. For musical duties, regulations from the Council of Basel were adopted, including the otherwise known prohibition against abbreviating the text of the Credo in unum Deum (which was often the case in polyphonic compositions). With regard to St Stephen’s, the visitors forbade the singing of Masses or Vigils in the two side choirs during Masses in the central choir (“ne tempore publici officii in choro Missae cum nota, aut vigiliae in lateribus chori decantentur”); the latter were only to be sung in other locations, sufficiently distant, and only “submissa voce” (in a subdued voice).[34] The hymns and psalms of the Divine Office were to be performed with pauses in the middle of the verses and in a low, not too loud voice.[35] This could be seen as a contrast to the “clear and loud” voice prescribed in Rudolf’s ordinances – although those refer specifically to antiphons. The terms “submissa voce” and “bassa voce” (in a low voice) also appear in a chapter ordinance from 1478 concerning services during Lent: according to this, Prime and Terce, including the antiphon up to the Elevation in the Marian Mass, were to be sung “submissa voce”, while a Requiem inserted before Terce was to be sung “bassa voce”.[36]

Church and university

In founding the ducal university college (Collegium ducale), Duke Albrecht III in 1384 granted the young university important access to the prebends of St Stephen’s Church by promising eight of the twelve professors of the college expectancies to canonries there. Rudolf IV had already established the personal union of the university chancellor with the provost of the chapter.[37] University services in Viennese churches and the participation of university members in processions were also regulated, as already outlined in Rudolf’s foundation (cf. Ch. Duke Rudolf’s regulations for the services at St Stephen’s). According to the statutes, the entire corporation took part in the feasts of St Gregory (12 March)[38] and St Benedict (21 March) at the Schottenkloster, and since 1472 also in the feast of St Augustine (28 August) at the Augustinian Church. The patron saint of the university was St George, on whose feast day (23 April) the deanery elections and graduation ceremonies were held.[39] Since 1385, the university held solemn processions on Marian feast days, leading to specific churches and monasteries: Candlemas on 2 February (St Stephen’s), the Annunciation on 25 March (Dominicans), the Assumption on 15 August (Carmelites), the Nativity of Mary on 8 September (Schotten), the Immaculate Conception on 8 December (Maria am Gestade), and since 1389 also the Visitation on 2 July (Dominicans).[40] Each faculty celebrated annual feasts in honour of their particular patron saints. The theologians celebrated the Apostle John (27 December) at the Dominican Church; the artists honoured St Catherine of Alexandria (25 November) at St Stephen’s; since 1429 the lawyers held their annual feast for St Ivo (19 May) in their faculty chapel; the medical faculty celebrated Sts Cosmas and Damian (27 September) at St Stephen’s.[41] For the medical feast, a procession was held with the saints’ relics; in 1436, 1465, and many later years, the cantor, organist, and “levites” (choirboys) of St Stephen’s took part in the Mass.[42] “Cantores” were also involved in the Catherine feast of the artists at least since 1412. Naturally, academic services were also held on other occasions and accompanied by music, especially on the patronal feasts of the various “nations”.[43]

Musical endowments up to c. 1420

The design and musical development of liturgical services in Viennese churches can be understood through three groups of documents: foundation charters, administrative records (e.g. accounts) and service orders (libri ordinarii). The chronological orientation of these types of sources differs greatly: while foundation charters aim to determine the future for all eternity, administrative records reflect the changing circumstances from year to year; service orders attempt to codify what already claims established status and is intended to remain in force.[44]

The wording of foundation charters is usually based on traditions that go far back before 1363. Daily and weekly Masses, even when sung, rarely included special musical additions. The most conventional form of liturgical foundation was the “Jahrtag” (anniversary), an annual commemoration of the dead. It comprised a vigil (Matins) on the preceding night, a Requiem Mass in the morning, and then a High Mass on the donor’s day of death. In his foundation charter of 28 October 1339, Jans der Sture, chaplain of the Corpus Christi altar at St Stephen’s, promised for the celebration of his anniversary: 60 d. to the parish priest, 1 tl. (240 d.) in total to eight “canons”[45], 24 d. each to the four vicars, 24 d. each to the schoolmaster, the sacristan, and the sexton, 12 d. to the cantor, 12 d. each to the four choirboys, as well as 60 d. for bell-ringing and ½ tl. (120 d.) for candle wax. In addition, 24 priests were to be present at the vigil during the night and to say the Requiem in the morning, for which they each received 20 d.[46] (» Fig. Choral endowment at St Stephen’s, Vienna, 1339)

The part of such a service sung by the cantor and pupils is never precisely identified in the sources, but as elsewhere, it was probably mainly psalm verses, responsory verses, and certain antiphons (in the Divine Office), as well as Alleluia verses and sequences (in the Mass). The pupils could certainly also sing choral sections together with the priests.

After 1363/1365, there were two cantors at St Stephen’s: the traditional one of the parish school and the new one of the chapter (cf. Ch. Personnel requirements for church music). They are mentioned separately, for example, in a memorial foundation dated 27 September 1378.[47] Here, the canons of St Stephen’s, including their cantor Bartholomaeus, confirm the memorial foundation of the citizen Lienhard der Poll (with Jacob der Poll, chaplain of the town hall chapel, appearing as a witness). In addition to the five chaplains who sing the Divine Office and each receive 35 d., four “choirboys” receive 18 d. each, the schoolmaster 32 d., the cantor 24 d., the accusator (school assistant or beadle) 14 d., the sacristan 16 d., the servants who prepare the altar 16 d., and the sacristan’s assistants who ring the bells receive 6 [small] shillings (= 72 d.) for their wine. The cantor mentioned after the schoolmaster and paid less is the school cantor; the chapter cantor Bartholomaeus is a co-author of the document.

In the testamentary endowment of the professor of medicine Niclas von Herbestorff (25 May 1420) for a weekly Mass in honour of the Holy Cross, it was stipulated under chapter cantor Ulreich Musterer that the Introit Nos autem gloriari and the sequence Laudes crucis attollamus were to be sung “mit der not”, i.e. according to the musical notation in the Gradual.[48] The chants mentioned belonged to the feast days of the Holy Cross (3 May and 14 September). The singing of the (complete) sequence was evidently a special task, even though polyphony is not mentioned here.

Foundation charters often require the involvement of the organ, as does the foundation of Rudolf IV. On 19 August 1402, for example, Dorothea, widow of Jörg Pallnhaymer, promises the “Orgelmaister” (here: organist) 24 d. for the Mass, the cantor likewise 24 d., and each of the four choirboys 12 d.[49]

In an extensive endowment by the brothers Rudolf and Ludweig von Tyrna for the Tirna or Morandus Chapel, established by their family (28 March 1403),[50] no pupils or cantors are required—only the organ. A main feature of the foundation, however, is the establishment of a Sunday Salve Regina during Lent. This highly popular Marian antiphon did not have a fixed place in ritual traditions; here, the reference is probably to an “addition” at the end of Marian Vespers or Compline, similar to the stipulation in the foundation charters of Rudolf IV. Isolated endowments of the Salve Regina, such as that of the future Viennese citizen Heinrich Franck in Bolzano (» E. Ch. The council’s Salve Regina), 1400, became occasions for polyphonic singing over the years.

Church and city accounts

The church accounts of St Stephen’s survive only from 1404 onward and are incomplete; those of St Michael’s begin only in 1433.[51] These contain various expenditures for the payment of musical services. At St Michael’s, the positions of organist and schoolmaster were already firmly established by 1433; from 1444, a cantor (“Chorschuler”) also appears.[52] At St Stephen’s, the cantor received ½ tl. (120 d.) annually from 1404 for singing the “chlag”, that is, the Lamentations of Jeremiah on Good Friday (» A. Ch. Tenebrae on Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday).[53] Also during Holy Week, as was common practice, the entire Psalter was recited. For this, 12 pupils were employed (under the direction of the accusator), each receiving 36 d. They were also given breakfast worth 26 d. In 1420 and 1422, breakfast was also provided to “zwei Hütern bei dem grab” (two guards at the tomb).[54] These two Holy Week services involved long texts that were to be recited rather than sung melodically. What was rewarded was the solemnity and effort of preparation, not a musical embellishment. Many of the churchwarden’s expenditures at St Stephen’s were for “singing in” (or on) “the organ”, as organ playing was called. The organist received 3 tl. annually for playing the small organ. This was certainly a positive organ that could be moved within the church, as the organist’s main duties (and additional income) came from foundations associated with various altars.[55] The organist was also paid for tuning[56] and minor repairs to this organ. During processions in the city, the organist remained in the church, where he played for the station service. He received special payment when he had to “sing in the great organ”,[57] namely on the feast days of Ash Wednesday (“Faschantag”), Ascension Day, the Tuesday before Pentecost, Pentecost, Midsummer Day (24 June), and the Feast of St Peter (22 February). These were evidently popular services. The organ playing may, as elsewhere, have alternated with the choir of priests and pupils. That the organist played Gregorian chants is suggested, among other things, by a payment in 1407 of 8 s. to the organist Hanns “umb ain Gradual” (for a Gradual), which he had probably purchased.[58]

The Viennese city accounts[59] provide evidence of festive organ playing during Masses at events organised by the city council (» E. Städtisches Musikleben). An organ was probably available at the town hall; since no official town organist is mentioned, church organists were probably called upon. In the 1420s, the city council paid the organist of St Stephen’s an annual salary of 8 tl. and listed him among the city’s employees, along with the “organ master” (at that time Jörg Beheim), who received 6 tl. This arrangement did not last: in 1436, it was noted that henceforth the churchwarden should pay the organist from the church funds;[60] however, occasional annual payments of 60 d. each continued for organ playing to the Te Deum. Apart from that, the St Stephen’s organist now lived on his salary from the churchwarden’s office (3 tl. for playing the small organ) and his many festive playing duties for both church and city council (» E. Städtisches Musikleben).

Tropes and other marginal phenomena in the Ordo of St Stephen’s

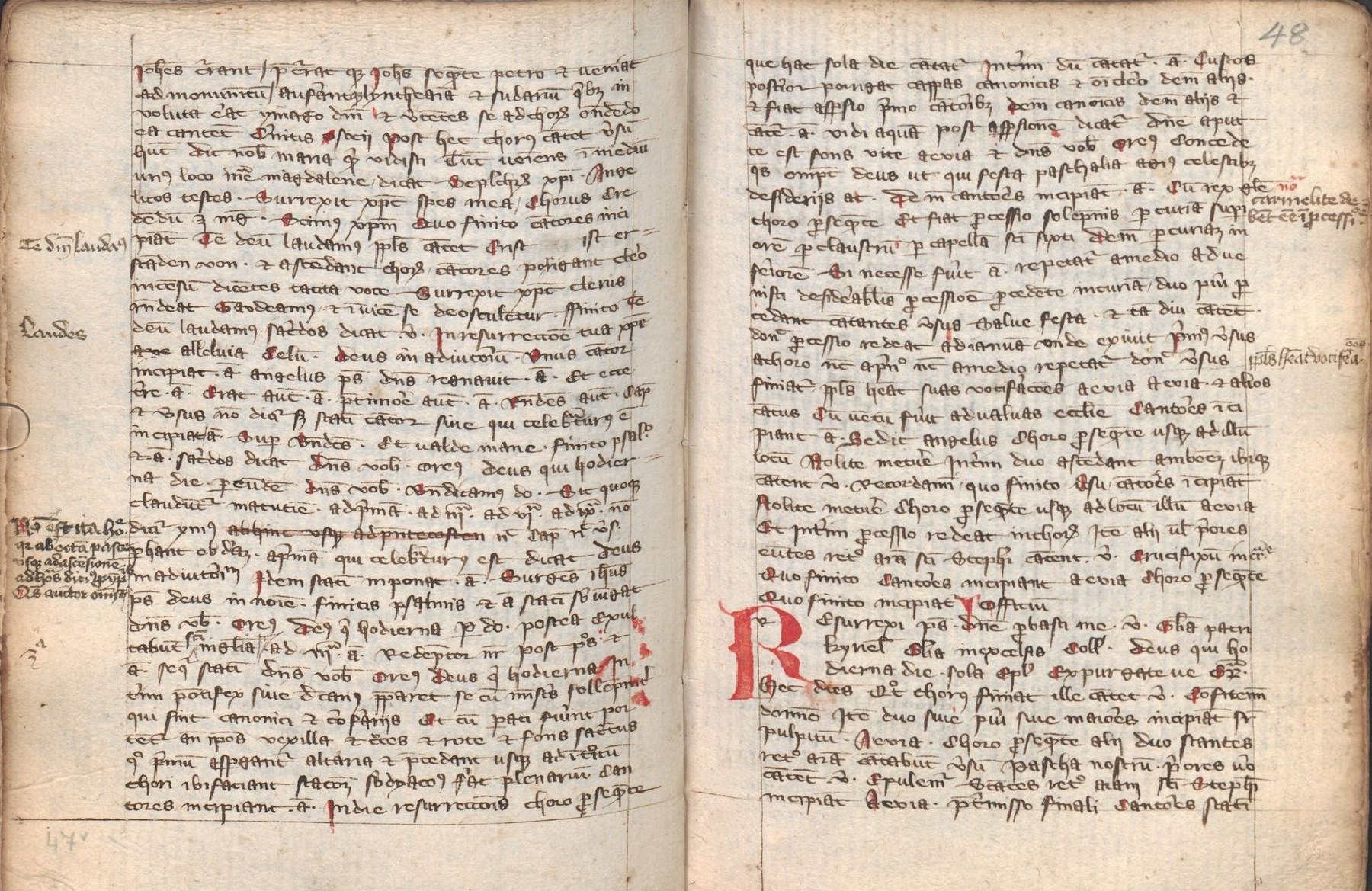

The compact volume » A-Wn Cod. 4712 of the Austrian National Library is labelled “ordo sive breviarium” (order or abbreviation). In it, the liturgical rite of St Stephen’s is described—much abbreviated, as is typical in such a Liber ordinarius—using incipits and rubrics instead of full texts.[61] Only the services of the chapter are listed, not those of the parish or the many privately endowed altars and chapels. The main text, written around 1400 (fols. 1–107), essentially conveys the Passau diocesan liturgy, which was used in the parishes of Vienna. Numerous marginal notes from the following decades explain the further development of the rite and its specific practice in Vienna. For example, a marginal note (fol. 9v) for the feast of St Stephen (26 December) states that (on the eve) no Compline is sung, but instead “a sermon is given to the clergy and the people” (fit sermo ad clerum et ad populum). For the Introit of the Mass on St Stephen’s Day itself, the main text prescribes unspecified tropes, possibly including the Introit trope De Stephani roseo sanguine martirii vernant primicie (From Stephen’s rose-red blood bloom the first fruits of martyrdom), which is recorded in the Seckau Cantionarius of 1345 (» A-Gu Cod. 756).[62] There are also Mass tropes for the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December), Epiphany (6 January), and other feasts of the year; none of these are preserved in the printed » Graduale Pataviense of 1511.

The organ is frequently mentioned in the service order of A-Wn Cod. 4712, especially in connection with the Marian Masses (e.g. fol. 28v). The main location of the small organ may have been at the Altar of Our Lady in the (northern) Marian choir.

A longer addendum on fol. 35v informs that, in accordance with a decree issued by the Bishop of Passau, Georg von Hachloch (Hohenlohe), on 12 November 1404, the entire Divine Office (Officium diurnum et nocturnum) is to be solemnly celebrated once a week with nine readings in honour of St Stephen, the diocesan patron of Passau. A second hand adds that this decree was solemnly read from the pulpit in the Chapter of St Stephen in Vienna on 1 June 1411.[63]

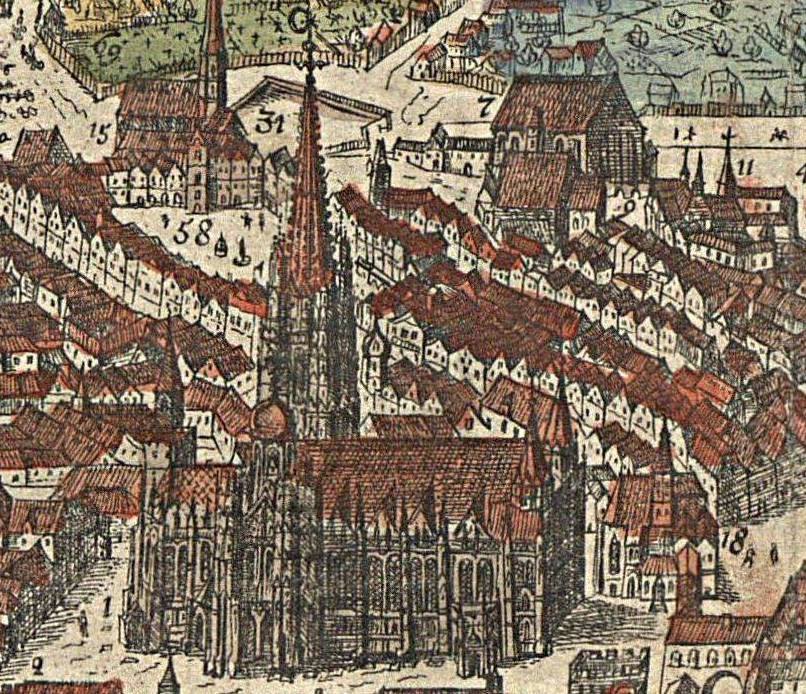

Specifically concerning Viennese customs, a note (fol. 50r) explains that on the octave of Easter, the rite of dedication of St Stephen is sung, whereby the Sunday after Easter (Quasimodogeniti) effectively became a second church consecration festival. On this Sunday, the “Heiltum”, the collection of all relics belonging to the church, was also shown to the people, from 1483 onwards on the specially constructed “Heiltumsstuhl” in front of the church (» Fig. Viennese Heiltumsstuhl; » F. Lokalheilige). On the preceding Saturday, the consecration festival of the Tirna Chapel (addendum on fol. 50r) was celebrated.

That vernacular songs were also part of the Easter celebration in Vienna (» A. Osterfeier) is evidenced by mentions of “cries of the people” in the main text (» Fig. Vociferationes populi). Further cries of the people were intended for the litany of the Rogation procession (cf. Ch. Processions of St Stephen’s).

Highly interesting is an isolated mention of polyphonic singing in the main text (fol. 54r), which is also found in other copies of the Passau Liber ordinarius and thus applied throughout the entire diocese (kindly communicated by Robert Klugseder). In the Mass of the fifth Sunday after Easter (Vocem iucunditatis), the sequence Laudes salvatori was sung, “which should be pleasantly concluded with discant” (que iocunde cum discantu finiatur). This refers to Notker’s prose Laudes salvatori for Easter Sunday, which was only fully replaced by Victime paschali laudes following the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century. In the second volume of his Choralis Constantinus (» G. Henricus Isaac), Isaac composed an Easter sequence in which Laudes salvatori (beginning with the second verse, Et devotis melodiis), Victime paschali, and even the antiphon Regina celi letare are combined. One must ask why such musical embellishment was prescribed for a comparatively unimportant Sunday[64], when it would have suited other feasts, such as Easter, at least equally well. Laudes salvatori was also sung on Easter Sunday (fol. 48v). Did the ordo here make something obligatory that could be done ad libitum on other days? It is proposed that this particular polyphonic contribution, probably performed by the priests (as cantor, schoolmaster or pupils are not mentioned), may have stemmed from an already long-established Passau foundation and was regarded as especially venerable. The type of discantus referred to here may have corresponded to that form of polyphony for which there is abundant evidence from monasteries in the region (» A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit).[65]

Processions of St Stephen’s

The Rogation processions (or litaniae maiores et minores) of the fifth week after Easter marked the close of the Easter season and the second Ember period of the liturgical year. On Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday of this week, the clergy of St Stephen’s, accompanied by priests and deacons bearing relics, banners and crosses, took part in Rogation processions, described in » A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r–55r.[66] Each time, the antiphon Exsurge and the psalm verse Salvum me fac were sung first, followed by the celebrant’s prayer In eternum familie tue intercedente beato Stephano, and then the antiphon Surgite sancti. The procession then exited the church, but in the event of rain (“si tempus fit pluviosum”), it passed only through the schoolhouse and across the cemetery (“claustrum”) into the crypt (“per czecham per claustrum in criptam”); two further antiphons followed, to which the laypeople were to contribute their own cries (“et layci habeant vociferaciones suas”). In fine weather, however (“si tempus serenum fuerit”), the procession continued into the “lower town” to St Mary’s, the Schottenkloster. Upon reaching the parish church of St Michael, the responsory Te sanctum dominum was to be sung, and upon entering the Schottenkloster, the responsory Salve nobilis virga. Here, the Mass prescribed for the day was celebrated, immediately followed by the litany (“nota officium letanie”, fol. 54v). Directly after the Benedicamus Domino of the Mass, the praecentor began the litany with Aufer a nobis iniquitatem, followed by the laypeople’s Kyrie eleison (“layci subiungant kyrieleison”); the clergy sang Miserere, miserere, again answered by the laity with Kyrie eleison. The choir then began Sancta Maria ora pro nobis ad Dominum, again answered by the laity with Kyrie eleison, and so forth. The content of the litany had to be adapted to the length of the return route, which led back after another station at the Schottenkloster. According to a marginal note (fol. 55r), on Tuesday the outward route passed via St Michael and the convent of St Mary Magdalene outside the Schottentor, while the return route led via the Carmelite convent (Am Hof) and St Peter’s.

St Michael’s played a special role in the more extensive Palm Sunday procession (fols. 38v–40v). As the procession passed by St Michael’s (“pretereuntes ecclesiam sancti Michahel”), the responsory Te sanctum dominum was first sung; upon entering the church, the responsory Salve nobilis was sung, answered by the “choir of women” (“Chorus dominarum”) with the verse Odor tuus. The singers were certainly the nuns participating in the procession. A second responsory, Ingressus Pylatus, was again answered by the women with the verse Tunc ait illis, and the “choir of men” (“chorus dominorum”) repeated the responsory. This responsorial style between women and men continued throughout the entire procession, the blessing of the palm branches, and the Mass in the Schottenkloster, as well as on the return route via the Bishop’s Court (“curia episcopi”, Maria am Gestade), where another station was held with alternating women’s and men’s choirs. Then, two boys in choir dress were to scatter the palm branches and carry a veiled cross, which was unveiled during the procession for the singing of the antiphon Pueri hebreorum and other appropriate chants. One might almost overlook in reading the ordo that, before arriving at Maria am Gestade, the laypeople were again permitted to insert a “vociferatio” (fol. 39r), which perhaps corresponded to the Palm Sunday hymn Gloria, laus et honor.

Development of the “Cantorey” (choir school) of St Stephen’s

Church and city accountsThe term “Cantorey” originally referred, as a translation of the Latin “cantoria”, only to the office of the cantor of a cathedral or collegiate church, but in Vienna, by 1403 at the latest, it was also used for the musical institution traditionally known in monasteries as “schola cantorum”. Thus, “Cantorey” could now also refer to the performing ensemble under the direction of the cantor or schoolmaster, or even to the place where it regularly assembled. A document from St Stephen’s dated 6 September 1403 names the cantor as “Petrenn cantor zu sand stephan und kaplan der messe auf sand dorotheen altar der zur cantorey gehört” (Petrenn cantor at St Stephen and chaplain of the Mass at the altar of St Dorothea, which belongs to the Cantorey);[67] in two documents from 1404, he appears as “Peter der Hofmaister die Zeit cantor dacz sand Stephan und Kappelan sand Dorotheen altar in der Schuler zech” (Peter Hofmaister, at that time cantor at St Stephen and chaplain of the altar of St Dorothea in the schoolhouse).[68] The churchwarden’s account of 1404 records extensive repair works (wood, nails, equipment, and labour costs) for the “cantorey auf dem letter” (Cantorey on the rood loft).[69] Thus, at that time, the Cantorey—as a physical location—was situated on the rood loft (Lettner) of the church, a gallery-like structure between the high choir and the nave; as an institution, it was an altar prebend for the cantor, endowed at the Dorothea altar[70] in the “Schülerzeche” (schoolhouse), and as a personal function, it belonged to the repeatedly attested cantor Peter (Hofmaister). As a chaplain, he was not a “civic cantor”, but neither was he the chapter cantor (who, as a canon, held the Rudolfinian prebend); rather, he was the school cantor.[71] The school cantor’s residence was located in the St Stephen’s cemetery near the schoolhouse or within the schoolhouse itself. The school Cantorey was largely financed until 1440 through altar prebends and other endowments, as well as income from the city council for singing the “chlag” (cf. Ch. Church and city accounts). Endowments exist from 7 April 1421 for 8 tl. annually in favour of the Mass belonging to the Cantorey, from 5 May 1445 for 6 tl. for the “Verweser” (administrator) of the Cantorey, and from 1449 for 12 tl. 4 s. also for the Cantorey.[72] A reliable chronology of the school cantors has not yet been established, as the distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor has often been neglected.[73] The following school cantors are known by name so far: Peter Hofmeister (1403/04), Johann von Neuburg (1405),[74] Sigmund Kunigswieser (1430), Peter der Marolt (d. 1444),[75] Hermann Edlerawer (1440–1444?), Conrad Lindenfels (1449–before 1457), Thomas List (1463–1467), Hans Payr (1469–1485), Wolfgang Goppinger (1486–1492).[76]

Hermann Edlerawer and the building of the Cantorey

Hermann Edlerawer from the Diocese of Mainz (» G. Hermann Edlerawer) came to Vienna by 1413/1414 at the latest, when he enrolled at the university. From the 1420s onwards, he served King Sigismund, and thereafter, until at least 29 April 1437, Duke Albrecht V. On 27 January 1436, he sealed a document as “official and land clerk of the Schottenkloster”.[77] Between 1440 and 1444, he is attested as school cantor of St Stephen’s (although he may have held the office as early as 1438 and until around 1449; evidence for this is lacking). His career was untypical for a church musician of the time. He first appears in the Vienna city accounts in 1438, when the council paid “dem hermanne” 10 tl.[78] Since no school cantor had previously received such a high salary from the city council, this may have concerned a special civic event (cf. Ch. Musical services of the Cantorey from c. 1440) or a reimbursement of expenses. In 1440, “hermanne cantori” was explicitly reimbursed 20 tl. for “building assistance for his Cantorey”, and in 1441 a further 12 tl.[79]

Until around 1440, music instruction by the school cantor in all likelihood took place primarily in the school. Elsewhere in Europe, rood lofts were indeed used for musical performances and often housed a small organ, but at St Stephen’s, the space on the lettner was significantly obstructed by other Masses and ongoing construction work.[80] Liturgical singing had to take place at the prescribed locations—also in the high choir—while no endowments involving the Cantorey are currently known for the altars on the lettner.

The Kantoreihaus—as the cantor’s residence and workplace—is mentioned for the first time in a document from 1438.[81] It was not a freestanding building, but was attached to the side of the Magdalene Chapel in the St Stephen’s cemetery (» Fig. Cantorey and Magdalene Chapel). The Magdalene Chapel formed the upper storey of the New Charnel House, which had been erected in 1304 above the old Virgil or Erasmus Chapel at the corner of the St Stephen’s cemetery. The chapel belonged to the Viennese Schreiberzeche, that is, the brotherhood of the city’s clerical officials (» E. Städtisches Musikleben; » E. Ch. Musikergenossenschaften).

That Hermann Edlerawer personally oversaw the construction or continuation of the Cantorey is evident, among other things, from a municipal legal dispute dated 5 November 1440: as already noted in the aforementioned document from 1438, the Cantorey building bordered the cemetery wall, on the other side of which stood the house of the apothecary Nicolas Laynbacher. Laynbacher sued the cantor over rainwater running off the tiled roof of the Cantorey onto his property. The ruling was in Edlerawer’s favour, as the Cantorey roof did not extend beyond the cemetery wall, and the wall itself was the property of the church.[82]

Previously, the Cantorey had no building of its own outside the church; singing was practised either in the school or in the church itself, which was disruptive alongside other activities. From now on, suitable pupils could be prepared for singing duties in a building specifically designated for that purpose. This advantage was confirmed by the 1446 ordinance for the civic school issued by the city council (» E. Städtisches Musikleben): it permitted the cantor to take suitable pupils out of the school for singing (but only before lunch), and not always all together for every singing duty, but rather different groups as needed. In return, it withdrew from him and his subcantor the classroom (“locatei”) in the school where the singing pupils had previously been taught together, regardless of their level of training (“irer begrifflichait”), which had led to “confusion in the choir”. Since the cantor and subcantor (assistant to the school cantor; cf. Ch. Personnel requirements for church music) were not only responsible for teaching music, one of them was to remain at the school for the other lessons after lunch. The final recommendation is important: if the arrangement did not suit him, the cantor could keep the boys at his house.[83]

“Item furbaser sol der kantor kain sundere locacein in der schul haben, als es auch vor jarnn gewesen ist. Wann er und ein subcantor von irrung des kors dieselben nicht wol verpesen mugen, sunder all schuler, die der cantor hat, sol man seczen nach gelegenhait irer begrifflichait, und wenn er sein schuler zu dem kor nuzen wil, so mag er sew vodern. Auch mugen im die locatenn ander knaben zuschickchenn, die fugsam sein zu dem kor, doch also das ein austailung werde der knaben, also das sy nicht all zu allen ambten geen, sunder yetz ain tail, darnach einn ander tail zu einem andern ambt. Darumb sol der cantor und sein subcantor gehorsam tun, und sullen vor essens alain dem kor wartenn. Aber nach essens sol ir ainer stetlich in der schul beleiben und den obristen locaten helffen zu lernen die schuler. Wer aber, das die vorgeschrieben weis von dem cantor nicht fugsam dewcht sein, so halt der cantor sein knaben in seinem haws fur sich selber.”

(Furthermore, the cantor shall not have a separate classroom in the school, as was the case in previous years. For he and a subcantor cannot properly improve the confusion in the choir, but rather all pupils under the cantor shall be placed according to their comprehension. And when he wishes to use his pupils for the choir, he may request them. By the classroom teachers he may also be sent other boys who are suitable for the choir, but in such a way that there is a distribution of the boys, so that they do not all serve in all services, but now one group, then another group for a different service. Therefore, the cantor and his subcantor shall obey, and shall attend to the choir only before the meal. But after the meal, one of them shall remain regularly in the school and assist the senior teachers in instructing the pupils. However, if the aforementioned arrangement does not seem suitable to the cantor, he may keep the boys at his house for himself.)[84]Thus, not only was a suitable rehearsal space for music created, but also a structural demonstration of the importance of church singing through the Cantorey, and at the same time of Hermann Edlerawer’s significance as cantor. There is scarcely any evidence elsewhere in contemporary Europe for dedicated Cantorey buildings. Yet it is no coincidence that at the Schottenkloster, where Edlerawer had served as administrator in 1436, a “singing room” (Singstube) was built between 1446 and 1449 under Abbot Martin von Leibitz (1446–1461).[85]

Musical services of the choir school since c. 1440

The musical duties of the Stephanskantorei increased significantly under Edlerawer. Whereas before 1440, not even for the Te Deum at public festivals was the participation of the singing pupils required—only that of the organist—there were, from around 1440 and continuing into the sixteenth century, the following types of liturgical services organised by the city administration with the school cantor:

- A “Mass of the Holy Trinity”, attested since 1438; it was sung, for example, in 1440 during negotiations between the city council and royal envoys in Hainburg, and on similar one-off occasions;[86]

- “Peace Masses” (Fridämter, probably intercessory services), often celebrated weekly over extended periods as civic Masses every Wednesday for political purposes; these were performed by the Cantorey with organ and bell ringing;[87]

- Festal Masses on the Friday before Reminiscere (Second Sunday in Lent) for the official gathering of citizens, prelates, and estates;[88]

- “Votive” Masses for political occasions, such as the departure of King Frederick to the Empire in 1444, held every Wednesday over twelve weeks until 11 November;[89]

- Masses “of the Holy Spirit”, later also called “votive”, celebrated annually for the inauguration of the newly elected city council;[90]

- From 1459 onwards, the singing of the responsory Tenebrae every Friday became the duty of the cantor and the choir pupils, accompanied by the ringing of the Salve Regina bell.[91]

A perhaps special occasion was celebrated at Reminiscere in 1444, when Hermann Edlerawer “served the prelates from the city and from outside the city” and received, by order of the council, 10 tl. for “this honour” (the same amount as recorded in the city account of 1438; cf. Ch. Hermann Edlerawer and the building of the Cantorey).[92]

The question remains as to which services were held at St Stephen’s itself and which perhaps took place at the town hall (the “honouring” of the estates at Reminiscere may belong to the latter), and in the latter case, which of these were conducted in the town hall chapel and where the organ—usually involved—was played. Just like the university, the city council sought to assert its political and representative role in the collegiate church as much and as often as possible, thereby making St Stephen’s, in effect, the council’s church. Edlerawer, owing to his dual qualification as a municipal official and musician, was a key link between the two spheres.

The Sacrament endowment of King Frederick III

In 1445, the Stephanskantorei was entrusted with perhaps the best-known duty of its early history, through a foundation by Frederick III, in which clerics from both St Stephen’s and St Michael’s were involved. Contrary to earlier assumptions, this royal foundation did not concern a “Corpus Christi procession”,[93] but rather the traditional priestly visits (Versehgänge) with the sacrament to sick parishioners within and outside the city. From now on, four poor boys (almsmen), dressed in brown choir robes and hoods, were to accompany each procession; they were to carry four small bells, two banners, and two glass lanterns with burning candles, and sing the hymn Pange lingua and the responsory Homo quidam fecit cenam magnam “hin und wider” (on the outward and return journey). In the church choir, during the daily Fronamt, two pupils were also to begin the verse Tantum ergo sacramentum (from the hymn Pange lingua) or Ecce panis angelorum (from the sequence Lauda Sion salvatorem), which was then to be sung by the school choir (cf. also » E. Transmission of Viennese church music).

And so that everything might be carried out “dester löblicher und ordenlicher” (all the more commendably and orderly), 32 choir robes and hoods, 32 banners in the Austrian colours (red-white-red), and 16 glass lanterns were to be kept ready and repaired or newly made as needed. These were provided by the founder; the city was responsible for maintaining the clothing and equipment.[94] Naturally, not all 32 boys accompanied each procession—whose number varied according to need—but only four at a time. The foundation income was transferred to the city by the king as a tax exemption on the treasury or “court tax” and amounted annually to between 44 and 54 tl., of which the cantor of St Stephen’s usually received between 40 and 47 tl., and the sacristan of St Michael’s (for bell-ringing) between 4 and 7 tl. Frederick III established similar foundations between 1441 and 1467 in Graz, Ljubljana, Wiener Neustadt and Linz.[95] A similar foundation was probably established in Bolzano in 1463 and is attested from 1472 onwards (» E. Corpus Christi Procession).

The Choir School after Edlerawer

It is uncertain to what extent Hermann Edlerawer (» G. Hermann Edlerawer) was still involved in the establishment of Frederick III’s sacrament foundation; in any case, from 1445 onwards, he was heavily engaged in the municipal chancery.[96] He undertook municipal duties such as official journeys, as well as assignments for the court and the university. When the payment of his municipal salary was discontinued in 1449 (he was only paid for two quarters of the year), it was probably no longer intended for Cantorey services.[97] The position of school cantor passed between 1445 and 1449 to Conrad Lindenfels, who is first mentioned as cantor at St Stephen’s in a document dated 13 November 1449. In 1457, Lindenfels received retrospective payment for “Fridämter” as a “former” (weilent) cantor.[98] In 1479, he became a canon and cantor of the church (which proves that his previous position had been that of school cantor); he died in 1488.[99]

In the school regulations of the civic school from 1446, provisions are made for a subcantor; this office was confirmed by the city council in 1461 with the establishment of a “locatei”, i.e. a teaching post, in the school for the subcantor, who was to teach the boys singing there – thereby revoking the school regulations of 1446. For this purpose, even two choir desks (pulpidum) were made by the carpenter.[100] In the Cantorey building itself, a “Tafel zum notirn” (board for notation) had already been set up in 1457, and a painter was commissioned “darauf zu malen” (to paint on it; evidently the musical staves).[101]

As a result of a testamentary donation by Ulreich Metzleinsdorfer in 1458 (A-Wda, Charter 14580930), a weekly Marian Mass was established as a duty of the cantor of St Stephen’s; this may have been held in the town hall chapel dedicated to Our Lady and may have been of musical significance. The corresponding income for the cantor amounted to 8 tl. annually.[102]

From 1478 at the latest, the school cantor was once again granted a municipal base salary of 12 tl. annually, as long as he held no priestly prebend (“dieweil er kain beneficium hab zur Besserung seines solds”).[103] This agreement, also referred to as a “Compactat”, remained in force at least until the end of the century. It probably reflects the increased musical demands placed on the Cantorey.

The choir school regulations of 1460 and the cultivation of polyphony

The Viennese municipal Cantorey ordinance for St Stephen’s, dated 24 September 1460 )[104], followed the municipal school ordinance of 1446 in a similar way as, in the history of the offices themselves, the cantor’s position (1267) followed that of the schoolmaster (1237): a more detailed scheme was derived from a broader framework. Such service ordinances must be examined particularly in terms of their position within temporal continuities: what innovations do they introduce or resist, what traditions do they affirm or oppose?[105] The Viennese Cantorey ordinance was certainly part of a broader trend among church administrations to respond to newer demands in musical practice with regulatory measures—thus acting restrictively or only cautiously encouraging. The ordinance addresses not only school discipline and organisation but also the musical repertoire, which evidently could be subject to debate. All pupils were to be trained in “cantus gregorianus” and “Conducten” (conductus). Gregorian chant was to be performed in church according to fixed distribution rules. By conductus, sacred songs were meant, which the poor pupils sang for money in front of houses during festive seasons (» E. Bozen/Bolzano; » H. Children’s Processions). In contrast, musically gifted pupils were to be trained in “cantus figurativus” (i.e. polyphony). And polyphonic singing was now required of them for the major feasts of Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. It is clear that the Cantorey ordinance did not seek to introduce something entirely new, but rather to regulate an already existing practice: the tradition of polyphonic singing, which had probably been in place for years (at the latest since Edlerawer). Its unchecked growth was now to be curbed—for example, by ensuring that only truly talented pupils were trained in it. The board set up in the Cantorey building in 1457 can be interpreted as a teaching aid for polyphonic singing and mensural notation, while the two reading desks installed in the school in 1461, used by the subcantor for instruction, served the “simpler” Gregorian chant (cantus planus), which was also sung in church from choir desks.

Polyphonic repertoire already existed at the civic school around 1410–1420, but at that time it was almost exclusively of foreign origin and cultivated by an elite (» K. The Viennese Codex of c. 1415). Edlerawer’s work, however, marks a phase of extensive collecting and original composition of polyphonic pieces for the representative functions of the Cantorey. All surviving and attributed compositions by Edlerawer are preserved in a single musical source, the “St Emmeram Codex” (» D-Mbs Clm 14274); this was at least begun in Vienna during his tenure as cantor (» E. Transmission of Viennese church music). It thus appears that the cantor influenced the creation of this collection and that the pieces recorded there reflect his musical liturgical duties at St Stephen’s. More than that, they define the musical capabilities of the pupil choir he trained—perhaps in such a way that not all pieces were intended for all choirboys, and that there were various levels and groupings of ability. This would be a principle also pursued by the school ordinance of 1446 for general subjects.

The Cantorey ordinance solidified the division of pupil groups into “general musicians” and polyphony specialists. Since cantus figurativus derived its name from the rhythmically fixed (mensural) note forms, the figurae, it did not include, for example, the non-mensurally notated monastic polyphony (» A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Arten und Kontexte) which is also attested at St Stephen’s under the name “Discantus” (cf. Ch. Tropes and other marginal phenomena in the Ordo of St Stephen’s). Only figured, mensural polyphony was conceptually and didactically treated as a distinct category—not the other forms of polyphony, which may have been practised frequently and informally, even by the general choir. This distinction can now be applied to the Cantorey’s book inventory of 1476. For the individual volume of the churchwarden’s accounts of St Stephen’s preserved by chance from that year[106] lists on fols. 184v–185r:

“die puecher, so der cantor hat in der cantorei:

In dem kar: ain Gradual, ain Salve puech, ain Passional.

In dem haus: zwai Gradual, zwen antiphonarii, dreu grosse Cancional des Hermans, ain gross Cancional des Jacobem, sechs klaine Cancional, ain rats Cancional mit ettlichen sexstern [these six words are crossed out], ain rats Cancional des Jacobem, ain alts Cancional mit ettlichen Sextern, klaine puechl mit proficein, das register des cantor.”

(The books that the cantor has in the Cantorey:

In the choir: one Gradual, one Salve book, one Passional.

In the house: two Graduals, two Antiphonaries, three large Cancionals by Hermann, one large Cancional by Jacob, six small Cancionals, one red Cancional with several sexterns [these six words are crossed out], one red Cancional by Jacob, one old Cancional with several sexterns, small booklets with Proficia, the cantor’s register.)The three large Cancionals are certainly to be attributed to Hermann Edlerawer, while the large and the red one “des Jacobem” refer to Jacob Gressing von Fladnitz, the former rector of the civic school.[107] The books attributed to them—i.e. evidently personally overseen by them—are exclusively designated as “Cancional”, and thus distinguished from the chant manuscripts (Antiphonale, Graduale, Passionale, etc.), some of which were kept in the church itself (in the choir). In 1455, the organist of Trent, Johannes Lupi—who had himself previously studied in Vienna—bequeathed his six-book collection of “cantionalia vel figuratus cantus” ( Cancionals, or cantus figuratus) to the parish church in Bolzano, using the terms “cancionale” and “figuratus cantus” almost synonymously in his will (» G. Johannes Lupi). If one accepts this nomenclature, then a total of five large and six small volumes in the Cantorey library of 1476 may have contained mensural polyphony—while the only other item, “ain alts Cancional mit ettlichen Sextern” (an old Cancional with several sexterns), was probably described as “old” precisely because its content was not mensural. It may further be assumed that the collecting and composing of mensural church music did not cease after Edlerawer’s departure, and that other cantors and subcantors were creatively involved in it. For the question of surviving musical sources from Vienna generally, see » E. Transmission of Viennese church music.

Two polyphonic endowments

So far, only two endowments at St Stephen’s from this period are known which, in unmistakable terms, call for mensural – that is, artfully polyphonic – music: from 1506 and from 1521. Since such music was not only cultivated but even prescribed from no later than 1460, this seems to require explanation. It is likely that polyphonic singing was also customary in endowed services – not only on high feast days in the high choir – but the documented contracts rarely specified this. The exceptions to be explained here are probably due to the particular musical interests and ambitions of their benefactors.

Dr Leonhart Wulfing, chaplain at St Stephen’s since 1479 and later canon and dean, bequeathed in his 1506 will an annual memorial on St Agnes’s Day at the St Agnes Altar, with three requiem masses and a “loblichen gesungen ambt von sannd agnesen mit dem cantor in figurativis und organis” (laudable sung mass of St Agnes with the cantor in figurativis and organis).[108] The patron saint was the protectress of the famous Viennese “Himmelpfort Convent” (also called St Agnes Convent) of the Premonstratensian canonesses in the Himmelpfortgasse near the cathedral, with whom connections presumably existed.

Georg Slatkonia (1456–1522), magister capelle of Maximilian I and, since 1513, Bishop of Vienna, established in 1521 extensive memorial endowments for himself, for which financial preparations had already been made since 1518 with the support of the Emperor. Slatkonia endowed, firstly, 500 thalers for a weekly mass, an eternal light, and an annual memorial at his grave to be erected in the Lady Choir beneath the altar of Saints Nicephorus, Primus, and Felicianus (charter dated 18 July 1521, A-Wda, Charter 15210718), and secondly, 500 Rhenish guilders for a mass on the Feast of the Assumption of Mary. This was to be sung “in mensuris” by the cantor with his fellows and by a canon with the organ, following the requiem of the memorial day and a procession (charter dated 19 July 1521: A-Wda, Charter 15210719). In addition, there were numerous provisions for the distribution of alms and the payment of priests and musicians. Clearly, a richly developed and far-reaching musical tradition was assumed, which was to be surpassed for the sake of the founder’s renown.

[1] Perger/Brauneis 1977; Schusser 1986, 17–41.

[2] Zschokke 1895, 2.

[3] Mantuani 1907, 209–210. Flotzinger 1995, 89–90. For general information on organs, see » C. Organs and Organ Music.

[4] Mantuani 1907, 209–210, suspects that the term “organist” refers to an organ builder, who was, however, referred to as “organ master” (e.g. “Petrein the organ master 15 tl” in the city accounts of 1380, » A-Wn Cod. 14234, fol. 39r). This designation is to be understood as a Germanisation of the term magister organorum.

[5] Incorrectly assumed for 1334 by Flotzinger 1995, 90. On the school cantor Peter Hofmaister, see Ch. Development of the Choir School of St Stephen’s.

[6] This and the following information on organs at St Michael’s according to Perger 1988, 91, and the churchwarden accounts in the College Archive of St Michael’s.

[7] On Hans Kaschauer and his father Jakob Kaschauer, who painted the large panel of the high altar between 1445 and 1448, see Perger 1988, 84.

[8] Schütz 1980, 14.

[9] Mayer 1880; Schusser 1986, 66, no. 31/1 (Richard Perger). The university confirmed this regulation on 14 April 1411: see Uiblein, Acta Facultatis 1385–1416, 355.

[11] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 15; Czernin 2011, 59.

[12] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 25.

[13] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 29.

[14] See Lind 1860, 11; Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1; Perger/Brauneis 1977, 275.

[15] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1.

[16] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 1935.

[17] Vienna City and State Archive, Charter 1935, 21 November 1412; see also Schusser 1986, 139, no. 115.

[18] Boyer 2008, 25.

[19] An attempt to distinguish between chapter cantor (“Sangherr”) and school cantor is made by Mantuani 1907, 287 f.

[20] Zschokke 1895, 25–48; Flieder 1968.

[21] Grass 1967, especially 464–467.

[22] Flieder 1968, 140–148, especially 148.

[23] Edited by Ogesser 1779, Appendices X and XI, 77–83. See also Flieder 1968, 155, 158–160.

[24] A statute from 1367 stipulated that the roles of “choirmaster” (magister chori) and dean should be united in one person (Göhler 1932/2015, 141 f.), which, however, apparently did not occur (Flieder 1968, 173 f.).

[25] Mantuani’s (Mantuani 1907, 288) mistaken equation of “choirmaster” with “cantor” has often been repeated. The German term for the latter was “Sangherr”. Ulreich senior (1365?) was “magister chori et cantor” (Göhler 1932/2015, 142 and fig. 11), i.e. the two titles were not synonymous. On the correct use of the terms, see Ebenbauer 2005, 14 f. (choirmaster responsible for the parish), although Mantuani is cited there without contradiction.

[26] On the location of altars and chapels, see Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61–63. I am sincerely grateful to Prof. Barbara Schedl for her advice in this regard.

[27] Ogesser 1779, 80–82. See the list of procession participants from a Liber ordinarius of St Stephen’s (» A-Wn Cod. 4712): » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[28] Zschokke 1895, 30–46; Flieder 1968, 254–266.

[29] Zschokke 1895, 33.

[30] In ecclesiastical service regulations, the Latin equivalent “alta voce” was traditionally used.

[31] Zschokke 1895, 37.

[32] Zschokke 1895, 40.

[33] Zschokke 1895, 84–91.

[34] Raimundus Duellius, Miscellanea, Augsburg/Graz 1724, Vol. II, 78 and 82.

[35] “Ne quis eciam nimium voces agitare aut in altum audeat elevare habeatque et cantum Bassum et nimis clamorosum ad medium reducere.” (Zschokke 1985, 89 f.) See also Rumbold/Wright 2009, 44.

[36] Archdiocesan Diocesan Archive Vienna (A-Wda), Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 107r.

[37] Grass 1967, 482–487.

[38] On 12 March 1421, over 200 Viennese Jews were burned in Erdberg by order of Duke Albrecht V, as reported, among others, by theology professor Thomas Ebendorfer (Lhotsky 1967, 370 f.).

[39] Zapke 2015, 87 f.

[40] Gall 1970, 85–86; Flotzinger 2014, 44–47, 54 f.

[41] Gall 1970, 34, 86 f.; Zapke 2015, 88 f.

[42] Pietzsch 1971, 27 f.

[43] Mantuani 1907, 283 and note 1; Enne 2015, 379 f.

[44] See Strohm, Ritual, 2014 on the temporal awareness of ecclesiastical regulations.

[45] “Canons” here refers to the “octonarii”, the priests of the collegiate chapter entrusted with pastoral care.

[46] A-Wda, Charter 13391028; see Currency: 1 pound (tl.) = 8 large (“long”) shillings (s.) = 240 pfennigs (d., denarii).

[47] Camesina 1874, 11, no. 36. The distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor is convincingly demonstrated in Göhler 1932/2015, 228 f.

[48] A-Wda, Charter 14200525; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/14200525/charter [02.06.2016].

[49] Camesina 1874, 21, no. 94.

[50] Camesina 1874, 21–23, no. 96.

[51] Accounts of the churchwarden’s office of St Stephen’s (in the Vienna City and State Archive), see Uhlirz 1902. Extracts from the account books of St Michael’s in Schütz 1980.

[52] Schütz 1980, 124. Schütz 1980, 15, mistakenly equates the schoolmaster with one of the two cantors.

[53] See Uhlirz 1902, 251 and elsewhere. Knapp 2004, 268, interprets this as a Marienklage (Lament of Mary), which is less likely from a liturgical perspective.

[54] Uhlirz 1902, 364, 384. The Easter sepulchre was an artistically crafted sculpture.

[55] On the locations of the organs, see also Ebenbauer 2005, 40 f.

[56] Uhlirz 1902, 337 (1417).

[57] For example, 1415: Uhlirz 1902, 299.

[58] Uhlirz 1902, 267 (1407).

[59] Vienna City and State Archive, 1.1.1. B 1/ Main Treasury Accounts, Series 1 (1424) etc.: hereafter abbreviated as OKAR 1 (1424) etc. (» A-Wsa OKAR 1-55).

[61] For detailed information on » A-Wn Cod. 4712 see Klugseder 2013; see also » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession. The liturgy of the St Stephen’s chapter is represented by the “Turs Missal” (c. 1430, produced under Provost Wilhelm von Turs), which still belongs to the Archiepiscopal Chapter and is of particular interest for art history.

[62] A-Gu Cod. 756, fol. 185r; see » A. Weihnachtsgesänge.

[63] The former is the earliest dated addition, indicating that the codex must have been created before 1404.

[64] However, the Sunday Vocem iucunditatis was dedicated to St Koloman (» A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r).

[65] For polyphonic conclusions to monophonic plainsongs, as seems intended here, there is evidence from the fourteenth century in France and Italy.

[66] The procession descriptions in the original corpus of » A-Wn Cod. 4712, a Liber ordinarius of the Diocese of Passau, replicate word-for-word the regulations for Passau itself (courtesy of Robert Klugseder), but are also applicable to Vienna due to the similar ecclesiastical topography of both cities. Added marginal notes clarify the route descriptions with direct reference to Vienna: Klugseder 2013 devotes a separate chapter to the Vienna-related marginalia in Cod. 4712. (See also the digital edition of the Passau Liber ordinarius, http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.passau). The Corpus Christi procession is represented in Cod. 4712 only by a brief marginal note on fol. 67v. However, the list of participants appears in the appendix (fol. 109r), edited in » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[67] Camesina 1874, 24, no. 101.

[68] Camesina 1874, 26, nos. 113 and 114 (12 and 13 December 1404).

[69] Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50 (Lohrmann).

[70] The claim that the Dorothea Altar stood in front of the rood screen (Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61 and note 214) cannot be derived from the records of 1403–1404. The altar’s income belonged “to the school corporation”, which in this context did not refer to a “brotherhood of pupils” (Lohrmann in Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50), but to the school building itself.

[71] Not to be confused with a canon of the same name, Peter of St Margrethen, active in 1399.

[72] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, nos. 2159 and 3076. 1449: OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 28v.

[73] Some of the information in Brunner 1948 is outdated.

[74] Göhler 1932/2015, 228, no. 98.

[75] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2978; a mention of “Peter Marold, cantor” in OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 19v, may refer to another cantor of the same name or be retrospective.

[76] All except Neuburg are listed in Czernin 2011, 87 f. This list also includes the chapter cantors Ulreich Musterer (†1426), Wolfgang von Knüttelfeld (†1473), Hanns Huber (1474), Brictius (1470s), and Conrad Lindenfels (1479–1488, previously school cantor 1449–1457); a “Kaspar” (1448) may be identical with choirmaster Kaspar Wildhaber (1423/24). The additional names in Flotzinger 2014, 57, note 49, all refer to “choirmasters”, whom Flotzinger, following Mantuani 1907 and Flieder 1968 mistakenly equates with cantors. See Ch. The institutional foundation of the St Stephen’s chapter.

[77] Melk, Abbey Archive, Charters (1075–1912), no. 1436 I 27, http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-StiAM/archive [02.06.2016].

[78] OKAR 5 (1438), fol. 92r.

[79] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 98r, and OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 111r.

[80] The latter note is based on kind information from Prof. Barbara Schedl, Vienna.

[81] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2656 (3 July 1438). Other, partly contradictory, details cited in Ebenbauer 2005, 38 f.

[82] A-Wda, Charter 14401105.

[83] See also Flotzinger 2014, 56 f.

[84] Boyer 2008, 36 f.

[85] Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1. On Martin von Leibitz and his Caeremoniale (A-Wn Cod. 4970), see Schusser 1986, 82, no. 65, and » A. Melk Reform.

[86] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 97v. The cantor received 60 d.

[87] For example, OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 112v (five weeks; from November before St Martin’s Day to St Lucy’s Day, 13 December).

[88] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 139v. In addition, 24 “peace masses” were sung daily until the Friday after Laetare (4th Sunday in Lent), for which “Hermann and the boys were paid 32 d. for each mass sung”.

[89] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 140r. The cantor received 21 d. for each “votive”. The dean, levites (probably choirboys), sacristan, and organist are also mentioned.

[90] For example, OKAR 9 (1445). The (unnamed) cantor received 3 s. (= 90 d.).

[91] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 3, no. 3848; Camesina 1874, 92–93, no. 437.

[92] OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 37r.

[93] As often stated in older literature, e.g. Strohm 1993, 507. Corrected in Rumbold/Wright 2009, 47.

[94] Camesina 1874, 78–80, no. 364 (1445, undated).

[95] See Weißensteiner 1993.

[96] OKAR 9 (1445), fol. 51r; the city accounts for 1446–1448 are lost. See Rumbold/Wright 2009, 48–50.

[97] OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 32r.

[98] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 3333 (for 1449); OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 41r.

[99] Zschokke 1895, 375; Rumbold/Wright 2009, 50–51. Lindenfels quickly became unpopular after his installation in 1479 by claiming, as chapter cantor, the right to choose his canon’s residence ahead of more senior canons (A-Wda, Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 18r).

[100] OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 82v. The total cost for the carpenter and locksmith (for iron bars to secure the choir books) amounted to 160 d.

[101] OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 118v. The total cost for the carpenter and painter amounted to 95 d.

[102] OKAR 16 (1458); OKAR 36 (1474), fol. 22r.

[103] OKAR 42 (1478), fol. 32v.

[104] Text provided, among others, in Mantuani 1907, 285–287; see also Gruber 1995, 199; Flotzinger 2014, 58 f.

[105] See Strohm 2014.

[106] Uhlirz 1902, 477.

[108] A-Wda, Charter 15060119; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/15060119/charter [02.06.2016].

Recommended Citation:

Reinhard Strohm: “Musik im Gottesdienst. Wien ”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musik-im-gottesdienst-wien-st-stephan> (2016).