Notations for polyphony in the Wolkenstein codices

The defining aspect of these repertories is that they are unmeasured, which, when applied to Oswald, appears to be a contradiction in terms since all his surviving music is notated mensurally. The use and meaning of mensural notes in the Wolkenstein codices, however, appear to differ according to context: while the scribes made standard use of the notational signs for the contrafacta to precisely regulate the interaction of the voices, they applied the mensural note shapes more creatively for the other group of songs, describing rather than prescribing a practice for which notation—in principle—was not required.[7]

This latter use of mensural note signs can be further differentiated, and – in its different forms – abundantly occurs also outside Oswald’s song manuscripts. It can, for instance, be found in the Neidhart œuvre of the Eghenvelder Liedersammlung (» B. Kap. Eine studentische Neidhartsammlung aus Wien), in the Lochamer-Liederbuch (D-B Mus. ms. 40613), or in the manuscripts containing the songs of the Monk of Salzburg (» B. Geistliche Lieder des Mönchs von Salzburg; » B. Secular Songs of the Monk of Salzburg). It manifests itself primarily in two forms: a semi-mensural and a structural use. The semi-mensural use can consist of mensural note signs in an otherwise non-mensural environment (for instance, chant notation) to clarify small-scale rhythmic relationships, such as upbeats, the placement of surplus syllables, and so on, or to provide a suggestion for a general performance rhythm. It can, however, also appear in the form of a seemingly precisely rhythmised melody. This special case of semi-mensural usage comes with a syllabic underlay of a German verse text with alternating stresses and usually consists of a regular alternation between a longer and a shorter note value in triple metre, usually semibrevis and minima, representing accented and unaccented syllables, respectively. Occasionally it also appears in duple metre. The resulting musical rhythm is a depiction of the verse metre of the underlying text and serves as a point of reference rather than a prescription for the performer, which is why I named it ‘reference rhythm’.[8] Since the reference rhythm is generated from the text (unlike the first and second rhythmic modes of the >Ars antiqua<) it is descriptive and implies performative flexibility. This, in turn, means that the essence of the melodic structure is not affected by a performative deviation from the rhythmic profile. Besides, what at first glance may look like a coherent use of mensural notation reveals numerous inaccuracies when looked at more closely. This semi-mensural use of mensural notation functions under the assumption that its meaning is clear from the context.

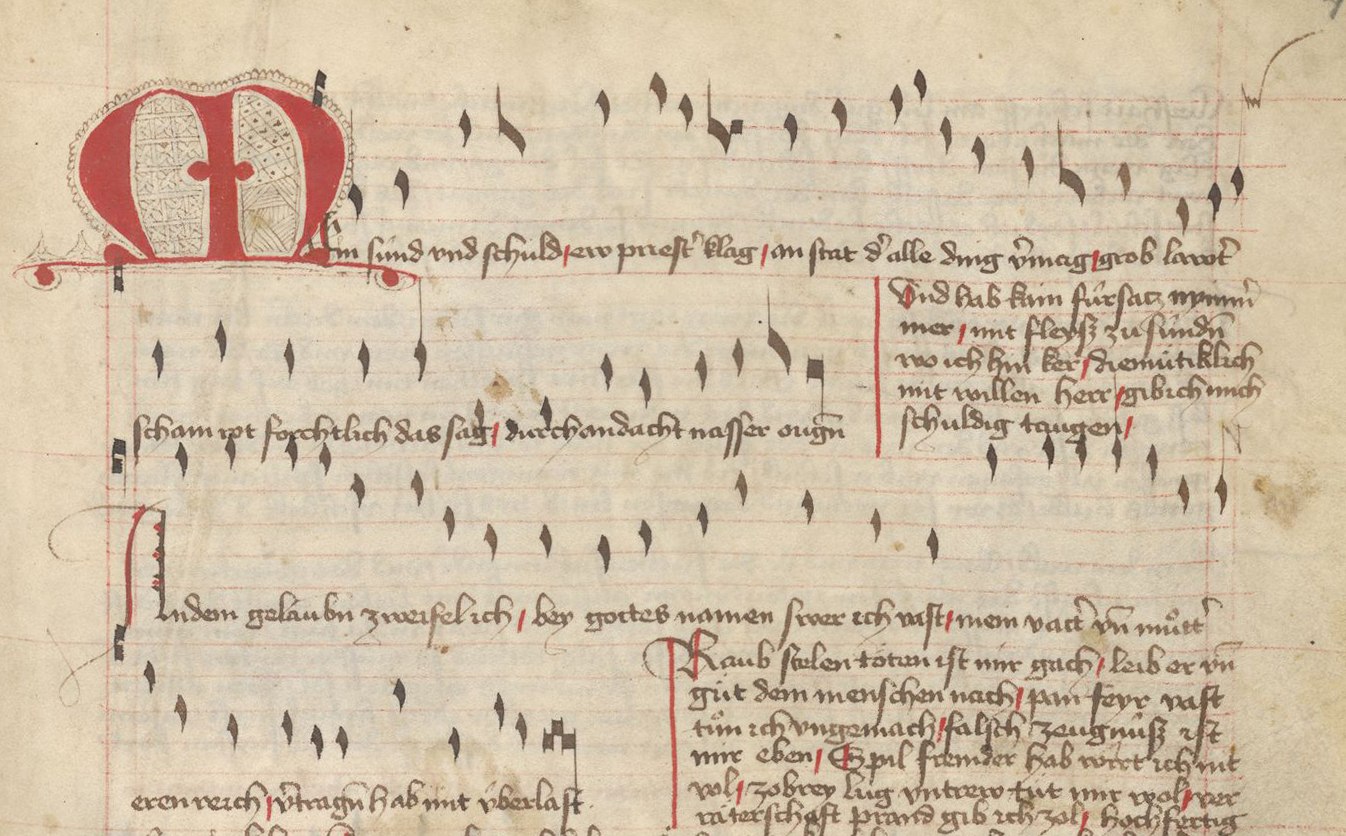

The other irregular use of mensural notation, the structural use, is non-mensural in essence. Mensural note shapes are employed here to visualise the structure of a melody with no hint at a performance rhythm: minimas represent upbeats, semibreves are equivalent to the puncta of chant notation and serve to notate the pitches of a melodic line, breves and longas indicate cadence notes, and the semiminima is occasionally used as custos (» Abb. Structural use of mensural note shapes, Oswald von Wolkenstein).

Although notations in pure reference rhythm as well as pure structural use can be found in all the above sources, both forms can also flow into each other and interact freely with other forms of semi-mensural notation, such as >stroke notation<.[9] All of them, however, are mainly reserved to record monophonic songs. Their use for some of the polyphonic pieces in the œuvre of Oswald von Wolkenstein clearly links this repertory to the world of monophony. In fact, the majority of this repertory appears to be equivalent to the concept of ‘cantus planus binatim’ (» Kap. Zum Begriff der nichtmensuralen Mehrstimmigkeit) a sort of ‘embellished’ or ‘enhanced monophony’ that employs a wide range of practices including fifthing (‘quintieren’) and extemporising upper voices (‘übersingen’): two techniques that are actually mentioned in Oswald’s song texts. And, as regards the term ‘binatim’ (‘in pairs’), all of the Oswald songs in question are for two voices.

Another comparable German repertory at the cross-roads between monophony and polyphony is the ‘polyphonic’ output of the Monk of Salzburg. Of his eight surviving polyphonic songs (all of them secular)[10] at least six contain aspects of non-mensural polyphony. Even though his compositions predate Oswald’s by at least one generation, the earliest transmitting sources appear only after the mid-fifteenth century, well after the Wolkenstein codices were written (WolkA, c. 1425; WolkB, c. 1432). The manuscripts with the Monk’s polyphonic songs present concordances in a wider range of sources and with a wider range of notations, including chant notation, which confirms this repertory’s affiliation to non-mensural polyphony as well as monophonic music. All voices in both repertories (Oswald’s and the Monk’s) are notated separately, according to contemporary custom – even though a notation in score format, which is usually found in the sources of sacred non-mensural polyphony (as for example » Abb. Viderunt omnes/Vidit rex, » Abb. Jube Domne – Consolamini), would have been more appropriate for a repertory that does not rely on exact rhythmic notation.

[7] Pelnar 1978, p. 275f.

[8] For a more comprehensive summary of the concept of ‘reference rhythm’, see Lewon 2012, 169–173.

[9] ‘Strichnotation’: see » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs and Glossary.

[10] The main manuscript for the songs of the Monk of Salzburg, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (A-Wn Cod. 2856), is one of the first musical manuscripts that makes a clear division between secular and sacred songs with the rubrics “werltlich” and “geistlich”; see März 1999, pp. 367–368.

[1] On these sacred repertories, see » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Grundlagen (Alexander Rausch), and » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Arten und Kontexte (Reinhard Strohm).

[2] Pelnar 1978, and substantiated in Pelnar 1982, Textband.

[4] “WolkA”: A-Wn Cod. 2777 (?Vienna, c. 1425): “WolkB”: A-Iu o. Sign.

[5] See Lewon 2017, pp. 134–137.

[6] This assessment supports Pelnar’s statement (Pelnar 1982, Textband, p. 21) against a development from a more ‘primitive’ to a more ‘sophisticated’ counterpoint within Oswald’s œuvre: ‘Auf keinen Fall dürfen die Gruppen [‘bodenständig’ und ‘westlich’] chronologisch als Entwicklungsphasen aufgefaßt werden, wie es etwa Salmen bei seiner Datierung der Lieder macht’ (Under no circumstances should the categories [‘native’ and ‘Western’] be understood as chronological phases of a development, as Salmen did in his dating of the songs).

[7] Pelnar 1978, p. 275f.

[8] For a more comprehensive summary of the concept of ‘reference rhythm’, see Lewon 2012, 169–173.

[9] ‘Strichnotation’: see » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs and Glossary.

[10] The main manuscript for the songs of the Monk of Salzburg, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (A-Wn Cod. 2856), is one of the first musical manuscripts that makes a clear division between secular and sacred songs with the rubrics “werltlich” and “geistlich”; see März 1999, pp. 367–368.

[11] ‘Kl’ numbers refer to the numeration in the standard text edition, Klein 2015 (and earlier).

[12] ‘W’ (‘weltlich’) numbers refer to the numeration in März 1999.

[13] The rubric to W 8 (Ich klag dir, traut gesell) by the Monk confirms this practice ex negativo: “Ain tenor von hübscher melodey als sy ez gern gemacht haben darauf nicht yeglicher kund übersingen” (A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they liked to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing an upper voice to this). See also » B. Kap. Ich klag dir traut gesell (David Murray).

[14] Lewon 2011; see the table on pp. 189-191. Not all of the remaining songs listed there are proven contrafacta, but their notation and counterpoint strongly suggest a model from contemporary polyphonic exemplars. There is one more piece that could be added to the list of twelve below: Kl 21 (Ir alten weib), a monophonic song that appears to be a cognate to the Neidhart song Der sawer kübell - Niemand sol sein trauren tragen lange (see Mark Lewon, ‘Oswald quoting Neidhart: Ir alten weib (Kl 21) & Der sawer kübell (wl)’ (2014), accessible online at: https://mlewon.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/oswald-quoting-neidhart/). Michael Shields (2011) has suggested that the third section of this Oswald song could contain a piece of hidden polyphony in the form of a fuga. Should this prove true, then Kl 21 could be another case of non-mensural polyphony, employing reference rhythm. Since the claim is hard to substantiate and canons are excluded from the list – most of them being contrafacta – I will, for the time being, leave this song aside.

[15] In WolkA, only Kl 79 was notated separately a few pages later, probably because it was added with a second layer of repertory. For the scribal layers of the manuscript, see Delbono 1977. In WolkB, song Kl 37/38 was separated from the block and notated in a monophonic version in the first half of the manuscript, while the other four were grouped together.

[16] A-Iu o. Sign. (?Basel, c. 1432).

[17] See chapter 5.3 ‘Oswald quoting Oswald: Crossing the Border to Polyphony’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 260–268.

[18] For an in-depth analysis of the modal shifts of Kl 101 in the different sources, see chapter 5.1 ‘“Wach auff, mein hort”: A Melody of Modal Ambiguity’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 241–53.

[19] A recording of this edition, though experimentally transposed to a D-mode, can be found on the album The Cosmopolitan – Songs by Oswald von Wolkenstein. Ensemble Leones (Christophorus, 2014), track 9. Other examples for a new edition of Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony can be found in Lewon 2016a, ‘Ach senliches leiden (Kl 51)’, pp. 35–37, and ‘Des himels trone (Kl 37)’, pp. 38–43.

[20] For a first proposal of this interpretation, see Lewon 2011, pp. 168–191 at pp. 182–184.

[21] In » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an, most melismas are in parallel fifths; the cadential melisma over the word ‘springen’ and a section of the final melisma of the clos, however, run in parallel sixths.

[22] März 1999. See also » B. The secular songs of the Monk of Salzburg (David Murray). The secular songs (‘W’ for weltlich), are edited in März 1999, the sacred songs (‘G‘ for geistlich), in Waechter-Spechtler 2004.

[23] Rubric: “Der tenor ist der tischsegen” (This tenor is [called] the benediction).

[24] Rubric: “Der tenor haizt der freüdensal nach ainem Lusthaws pey Salzburg […]” (This tenor is called the house of pleasure after a hunting lodge near Salzburg […]).

[25] Rubric: see n. 13 above.

[26] For a more formal definition of monophonic ‘tenores’, see März 1999, pp. 11–2, 14–19, 31–3 and 36–40. An extended interpretation of the use and function of such ‘tenores’ by Reinhard Strohm and myself is given in Lewon 2018, pp. 225–226.

[27] In fact, Lorenz Welker argued that the motet-like song W54* is an example of extemporised counterpoint, which needed to be written because it carries a text. In other circumstances the discantus would not have been notated, but extemporised: see Welker 1984/1985, p. 55.

[28] Melody rubric: “Das nachthorn, vnd ist gut zu blasen” (The night horn, and it is suitable for wind instruments); second voice rubric: “Das ist der pumhart dar zu” (This is the accompanying bombarde).

[29] Melody rubric: “Das taghorn, auch gut zu blasen, vnd ist sein pumhart dy erst note vnd yr ünder octaua slecht hin.” (The day horn, also suitable for wind instruments, and its bombarde is simply the first note down an octave).

[30] See Welker 1984/1985.

[31] Rubric: “Das kchühorn […]” (The cow horn […]).

[32] Melody rubric: “Das haizt dy trumpet vnd ist auch gut zu blasen. Das swarcz is er, das rot ist sy” (This is called the trumpet and it is also suitable for wind instruments. The black [notation and text] is him, the red [notation and text] is her). Second voice rubric: ‘Das ist der wachter dar zu’ (This is the watchman for this).

[33] See März 1999, p. 368.

[34] On the musical types trumpetum and tuba (‘trompetta music’), see Strohm 1993, pp. 108-111 and passim.

[35] See » E. Kap. Hornwerke, where it is now suggested that a Hornwerk may have existed in the 15th century on the tower of the Salzburg parish church or of the town hall.

[36] März 1999, pp. 12 and 368.

[37] Both of them feature a dialogue of two lovers in their main melody, accompanied by a running commentary in the second voice.

[38] März 1999, p. 375.

[39] A recording is » Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn (Ensemble Leones), https://musical-life.net/audio/untarnslaf-das-kchuhorn (2015), where I refer to this song as a ‘pseudo-’ or ‘peasant-motet’.

[40] A stylised semiminima is used as the custos throughout the section with polyphonic songs and monophonic ‘tenores’.

[41] See Welker 1984/1985.