Trumpet and horn-signal songs

The imitation of horn or trumpet signals in vocal music was well established by the late fourteenth century and is not unique to the Monk of Salzburg. It can, for instance, be found in other contemporary repertories such as the Ars nova chace and the Trecento caccia.[34] However, a distinction should be made between the three songs with horn imagery in the title (W 1, W 2, W 3) and the ‘trumpet’ (W 5). While the melodic profile of the ‘trumpet’—even with its tendency towards more and wider leaps—does not appear to deviate significantly, its rhythmical structure is much more pronounced, obviously imitating trumpet signals. The melodies of the ‘night horn’ (W 1), the ‘day horn’ (W 2), and the ‘cow horn’ (W 3), on the other hand, move much slower and smoother by comparison, maybe imitating typical call signs of horn instruments. Reinhard Strohm has proposed a new interpretation for the names of the first two melodies: the soundscape of late medieval Austrian cities included the so-called ‘Hornwerke’, usually simply referred to as ‘Horn’ in contemporary sources (» Kap. Hornwerke). These were organ-like instruments installed on church towers or fortifications; when activated by the means of bellows, they emitted a far-carrying sound. One ‘Hornwerk’ that was installed at the Salzburg castle in 1515 played a multiplex F major chord – whether also a melody is not known.[35] The one installed at St Stephen’s church in Vienna in 1456 was once referred to as ‘Taghorn’. It seems that the signals were maintained and used by the secular authorities to announce specific times of the day, which included the announcement of certain laws, such as curfews. The three horn-like melodies by the Monk might, therefore, reference these ‘Hornwerke’ and their associated functions in daily city life rather than actual horn signals. This reference might also explain why they were notated with second voices, enhancing their sound possibly to better imitate the effect of a ‘Hornwerk’.

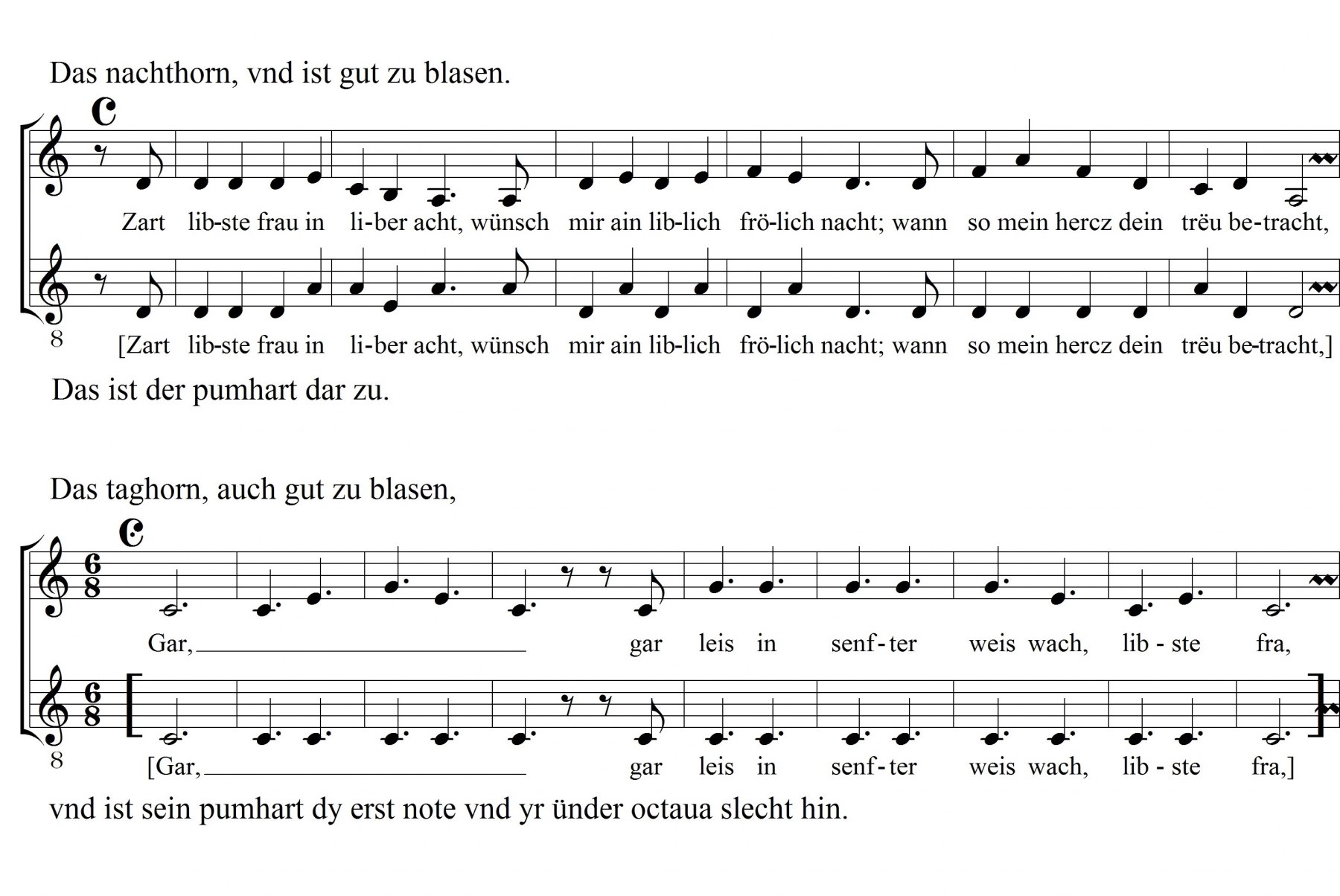

The horn-like songs have something else in common: Two of them (W 1, W 2) have a second voice called ‘pumhart’ (‘bombarde’ or bass shawm) in the accompanying rubric and feature unique C1 and C2 clefs for their texted voices. This transposes them into the discantus range, while their second voices, the ‘pumharts’, occupy the lower tenor range. Both ‘pumharts’ have a drone-like appearance and the ‘pumhart’ for W 2 is not even notated, but only described in the rubric as the first note of the song down an octave (c). However, what at first sight might seem nothing more than the description of a continuous drone that could be applied to a plenitude of melodies, turns out to be carefully planned. The melody employs only the notes c’, e’, g’, a’, and c” (with one passing minim f’) in the entire melody, thus creating a completely consonant contrapunctus simplex with the described ‘pumhart’ on c. In practice, the ‘pumhart’ note would probably have been repeated with each note of the cantus to accommodate the entire text, just as in the notated ‘pumhart’ of W 1.[36] The name for these accompanying voices was probably derived from their low range and at the same time extended the metaphor of a wind instrument. It does not seem to imply an intended instrumentation. All concordances to these two songs are monophonic, notated down a fourth, fifth, or octave (that is, in the normal tenor range), and transmit the melodies without their ‘pumharts’. See » Notenbsp. Das Nachthorn & Das Taghorn.

Das Kchuhorn (W 3)

With some caution, the next song in the manuscript, W 3, could be argued to fall into the same category as W 1 and W 2. Its intended form and polyphonic structure are not at all clear from the manuscript layout. Since it is grouped with the polyphonic pieces and has a comparable form to the motet-like W 5,[37] März plausibly suggested a heterophonic structure: both voices of the song have the same basic melody with the ‘tenor’ in slower note values, while the ‘discantus’ has a diminuted version.[38] Sung together the two melodies result in a motet-like heterophonic structure that perfectly matches the low stylistic level of the text: where in W 5 the composition re-enacts a classic medieval aubade, W 3 transfers the setting from dawn to a lunch-time nap and from the courtly chamber to the stables. (» Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn.) The music does the same, compressing a more artistic, polyphonic setting, such as W 5, into the bucolic realm of the peasants, who have to make do with a ‘monophonic motet’. In my interpretation of this song, I went a step further and, following the lead of the notations for W 1 and W 2, transposed the ‘discantus’ up an octave to further differentiate the voices and their functions, thus transforming the ‘tenor’ into a ‘pumhart’.[39] The process of adding a lower voice to the main melody in the three horn-like pieces needs to be distinguished from the practices of fifthing and discanting, in which the new counterpoint is added above the main melody. The Monk’s ‘pumharts’ could be compared to some of those songs by Oswald (see the group of pieces marked with (+): Kl 84, Kl 51 and Kl 91, above), where it is difficult to discern the cantus prius factus and where drone-like passages occur in the lower voice. These could indeed be cases of ‘pumharting’, where the added voice is the tenor.

[34] On the musical types trumpetum and tuba (‘trompetta music’), see Strohm 1993, pp. 108-111 and passim.

[35] See » E. Kap. Hornwerke, where it is now suggested that a Hornwerk may have existed in the 15th century on the tower of the Salzburg parish church or of the town hall.

[36] März 1999, pp. 12 and 368.

[37] Both of them feature a dialogue of two lovers in their main melody, accompanied by a running commentary in the second voice.

[38] März 1999, p. 375.

[39] A recording is » Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn (Ensemble Leones), https://musical-life.net/audio/untarnslaf-das-kchuhorn (2015), where I refer to this song as a ‘pseudo-’ or ‘peasant-motet’.

[1] On these sacred repertories, see » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Grundlagen (Alexander Rausch), and » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Arten und Kontexte (Reinhard Strohm).

[2] Pelnar 1978, and substantiated in Pelnar 1982, Textband.

[4] “WolkA”: A-Wn Cod. 2777 (?Vienna, c. 1425): “WolkB”: A-Iu o. Sign.

[5] See Lewon 2017, pp. 134–137.

[6] This assessment supports Pelnar’s statement (Pelnar 1982, Textband, p. 21) against a development from a more ‘primitive’ to a more ‘sophisticated’ counterpoint within Oswald’s œuvre: ‘Auf keinen Fall dürfen die Gruppen [‘bodenständig’ und ‘westlich’] chronologisch als Entwicklungsphasen aufgefaßt werden, wie es etwa Salmen bei seiner Datierung der Lieder macht’ (Under no circumstances should the categories [‘native’ and ‘Western’] be understood as chronological phases of a development, as Salmen did in his dating of the songs).

[7] Pelnar 1978, p. 275f.

[8] For a more comprehensive summary of the concept of ‘reference rhythm’, see Lewon 2012, 169–173.

[9] ‘Strichnotation’: see » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs and Glossary.

[10] The main manuscript for the songs of the Monk of Salzburg, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (A-Wn Cod. 2856), is one of the first musical manuscripts that makes a clear division between secular and sacred songs with the rubrics “werltlich” and “geistlich”; see März 1999, pp. 367–368.

[11] ‘Kl’ numbers refer to the numeration in the standard text edition, Klein 2015 (and earlier).

[12] ‘W’ (‘weltlich’) numbers refer to the numeration in März 1999.

[13] The rubric to W 8 (Ich klag dir, traut gesell) by the Monk confirms this practice ex negativo: “Ain tenor von hübscher melodey als sy ez gern gemacht haben darauf nicht yeglicher kund übersingen” (A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they liked to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing an upper voice to this). See also » B. Kap. Ich klag dir traut gesell (David Murray).

[14] Lewon 2011; see the table on pp. 189-191. Not all of the remaining songs listed there are proven contrafacta, but their notation and counterpoint strongly suggest a model from contemporary polyphonic exemplars. There is one more piece that could be added to the list of twelve below: Kl 21 (Ir alten weib), a monophonic song that appears to be a cognate to the Neidhart song Der sawer kübell - Niemand sol sein trauren tragen lange (see Mark Lewon, ‘Oswald quoting Neidhart: Ir alten weib (Kl 21) & Der sawer kübell (wl)’ (2014), accessible online at: https://mlewon.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/oswald-quoting-neidhart/). Michael Shields (2011) has suggested that the third section of this Oswald song could contain a piece of hidden polyphony in the form of a fuga. Should this prove true, then Kl 21 could be another case of non-mensural polyphony, employing reference rhythm. Since the claim is hard to substantiate and canons are excluded from the list – most of them being contrafacta – I will, for the time being, leave this song aside.

[15] In WolkA, only Kl 79 was notated separately a few pages later, probably because it was added with a second layer of repertory. For the scribal layers of the manuscript, see Delbono 1977. In WolkB, song Kl 37/38 was separated from the block and notated in a monophonic version in the first half of the manuscript, while the other four were grouped together.

[16] A-Iu o. Sign. (?Basel, c. 1432).

[17] See chapter 5.3 ‘Oswald quoting Oswald: Crossing the Border to Polyphony’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 260–268.

[18] For an in-depth analysis of the modal shifts of Kl 101 in the different sources, see chapter 5.1 ‘“Wach auff, mein hort”: A Melody of Modal Ambiguity’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 241–53.

[19] A recording of this edition, though experimentally transposed to a D-mode, can be found on the album The Cosmopolitan – Songs by Oswald von Wolkenstein. Ensemble Leones (Christophorus, 2014), track 9. Other examples for a new edition of Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony can be found in Lewon 2016a, ‘Ach senliches leiden (Kl 51)’, pp. 35–37, and ‘Des himels trone (Kl 37)’, pp. 38–43.

[20] For a first proposal of this interpretation, see Lewon 2011, pp. 168–191 at pp. 182–184.

[21] In » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an, most melismas are in parallel fifths; the cadential melisma over the word ‘springen’ and a section of the final melisma of the clos, however, run in parallel sixths.

[22] März 1999. See also » B. The secular songs of the Monk of Salzburg (David Murray). The secular songs (‘W’ for weltlich), are edited in März 1999, the sacred songs (‘G‘ for geistlich), in Waechter-Spechtler 2004.

[23] Rubric: “Der tenor ist der tischsegen” (This tenor is [called] the benediction).

[24] Rubric: “Der tenor haizt der freüdensal nach ainem Lusthaws pey Salzburg […]” (This tenor is called the house of pleasure after a hunting lodge near Salzburg […]).

[25] Rubric: see n. 13 above.

[26] For a more formal definition of monophonic ‘tenores’, see März 1999, pp. 11–2, 14–19, 31–3 and 36–40. An extended interpretation of the use and function of such ‘tenores’ by Reinhard Strohm and myself is given in Lewon 2018, pp. 225–226.

[27] In fact, Lorenz Welker argued that the motet-like song W54* is an example of extemporised counterpoint, which needed to be written because it carries a text. In other circumstances the discantus would not have been notated, but extemporised: see Welker 1984/1985, p. 55.

[28] Melody rubric: “Das nachthorn, vnd ist gut zu blasen” (The night horn, and it is suitable for wind instruments); second voice rubric: “Das ist der pumhart dar zu” (This is the accompanying bombarde).

[29] Melody rubric: “Das taghorn, auch gut zu blasen, vnd ist sein pumhart dy erst note vnd yr ünder octaua slecht hin.” (The day horn, also suitable for wind instruments, and its bombarde is simply the first note down an octave).

[30] See Welker 1984/1985.

[31] Rubric: “Das kchühorn […]” (The cow horn […]).

[32] Melody rubric: “Das haizt dy trumpet vnd ist auch gut zu blasen. Das swarcz is er, das rot ist sy” (This is called the trumpet and it is also suitable for wind instruments. The black [notation and text] is him, the red [notation and text] is her). Second voice rubric: ‘Das ist der wachter dar zu’ (This is the watchman for this).

[33] See März 1999, p. 368.

[34] On the musical types trumpetum and tuba (‘trompetta music’), see Strohm 1993, pp. 108-111 and passim.

[35] See » E. Kap. Hornwerke, where it is now suggested that a Hornwerk may have existed in the 15th century on the tower of the Salzburg parish church or of the town hall.

[36] März 1999, pp. 12 and 368.

[37] Both of them feature a dialogue of two lovers in their main melody, accompanied by a running commentary in the second voice.

[38] März 1999, p. 375.

[39] A recording is » Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn (Ensemble Leones), https://musical-life.net/audio/untarnslaf-das-kchuhorn (2015), where I refer to this song as a ‘pseudo-’ or ‘peasant-motet’.

[40] A stylised semiminima is used as the custos throughout the section with polyphonic songs and monophonic ‘tenores’.

[41] See Welker 1984/1985.