Instrumental Music Practice in the Life of Augustin Schubinger (c. 1460–1531/32)

Instrumental Music Practice: Preliminary Note

The essay H. Instrumental Music Practice by Markus Grassl, together with » G. Augustin Schubinger (English) (Markus Grassl), forms an extended biography of this significant musician who served the Habsburgs for decades. The essay is complemented by » I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I (Martin Kirnbauer) and » H. Minstrels and Instrument-Makers in Maximilian’s realm (Helen Coffey) to provide a more comprehensive depiction of instrumental music in Central Europe around 1500.

“mit Pusaunen vnd andern Instrumenten Musicalien der Ich dan yezo jn vbung bin” (with trombones and other musical instruments that I am now practicing)

As was typical for a professional instrumentalist of his time, Augustin Schubinger mastered several instruments. He confirms this himself with his remark “mit Pusaunen vnd andern Instrumenten Musicalien der Ich dan yezo jn vbung bin” (with trombones and other musical instruments that I am now practising)[1]. Sources such as Emperor Maximilian’s Triumphzug, Lalaing’s travel report, documents from the Burgundian court and the account books of German cities, which refer to Schubinger as “joueur de lut et de cornet”, “lutinist”, or “Zinkenblaser”, use more specific terms that clearly denote the respective instrument (» G. Augustin Schubinger (English). However, with other titles encountered in sources for Schubinger we face the notorious problem of the often ambiguous or inconsistent instrument terminology of the time. Terms like “Pfeifer” (piper) and “Trompeter” (trumpeter), occasionally used for Schubinger,[2] could refer to any instrument of the alta capella or various brass instruments, including field trumpets, slide trumpets or trombones. The term “Posauner” (trombonist), on the other hand, can have either a generic or specific meaning depending on the location, institution or source. The sources from Maximilian’s court administration, in particular, do not always mean the actual trombone but include all instruments belonging to the alta capella, including the cornett.[3] In contrast, the Augsburg account books (Baumeisterbücher) since 1487 regularly distinguish one of the four city musicians with the addition “busaner” (trombonist) from the other “pipers”. This applies to Schubinger[4] as well as his successor Baltasar Diettel[5] (in 1488, the year after Schubinger’s departure, there is even explicit mention of the “neue Busaner” (new trombonist)[6]). Florentine sources also tend to use a more precise language, normally distinguishing between the (sometimes slightly better-paid) “trombone” and the other “piffari”.[7] It may therefore be assumed that Schubinger functioned as a trombonist both in the Augsburg city piper ensemble and in the Florentine alta cappella.

Whether Schubinger also learned to play other instruments belonging to the alta capella, namely the soprano shawm or the Pommer (alto or tenor shawm), is not directly verifiable, but quite likely, given the standard expected of professional wind instrumentalists. (» Hörbsp. ♫ Missa La Spagna, Agnus Dei 1; Missa La Spagna, Agnus Dei 2; Missa La Spagna, Agnus Dei 3.)

Additionally, there is evidence that Schubinger’s father and his brother Michel played the Pommer: It is known that Ulrich the Elder succeeded the departing “Scharpffhanns Bomharter” in the Augsburg city piper ensemble in 1457, presumably taking over his role as a Pommer player.[8] The same probably applied to Michel if he represented his father as an Augsburg city piper between 1472 and 1476.

Schubinger and the Cornett

Schubinger is explicitly mentioned as a cornett player only in sources after his time in Florence. Based on this, and the fact that Giovanni Cellini, a Florentine piffaro between 1480 and 1514, played the cornett and taught his (much more famous) son Benvenuto,[9] Keith Polk concluded that Schubinger might have mastered this instrument during his stay in Italy.[10] Although this cannot be definitively ruled out, considering the overall evidence for the early appearance of the cornett, it becomes clear that the instrument had already gained a foothold in the German-speaking world by the late fifteenth century, whereas it seems to have become more wide-spread in Italy only after the turn of the sixteenth century.[11] ( »H. Zink / Cornett). Against this background, it is also conceivable that Schubinger had already come into contact with the cornett in Augsburg, even if there is no direct evidence for this.

Apparently, the cornett was the instrument on which Schubinger primarily excelled from around 1500 (which would justify his reputation, today, as “the first truly famous virtuoso on the instrument [i.e. the cornett]”[12]). It was not uncommon in the fifteenth century for a professional musician to focus primarily on one of the instruments they mastered. There are indications that within alta ensembles, individual players specialised in a specific instrument and thus a specific voice (as was the case with Schubinger as the trombonist of the Augsburg and Florentine wind ensembles). Adding to this, the impression that in later times Schubinger’s preferred instrument was solely the cornett is based on prominent sources such as Lalaing’s travel description or the Triumphzug, which refer to music-making in representative and public contexts. However, payment records from Mechelen, Konstanz and Nuremberg from 1508 to 1517 repeatedly refer to Schubinger as “lutinista domini Cesaris”, “luytslager vanden keyser”, and so forth.[13] The fact that he was still perceived as a lute player suggests that he still played this instrument. He may have primarily played it in informal settings, which did not leave a mark in prominent sources intended for the genral public.

Schubinger and the Lute

It was not uncommon around 1500 for a wind player to also master string instruments, particularly the lute (reflecting a general development of the time, namely the gradual dissolution of the boundary between “loud” and “soft” instruments). Several musicians, including Schubinger’s brothers Michel and Ulrich the Younger or Giovanni Cellini, were known to play the lute, harp, and/or “viola” in addition to wind instruments.[14]

Schubinger’s lifetime coincided with a phase in which lute technique underwent a fundamental change: the transition from playing with a plectrum to plucking the strings with the fingertips. This innovation promoted the establishment of the lute as a solo instrument on which an individual could perform polyphonic pieces.[15]. Until then, the lute was typically played in ensembles. From around 1450, it was found particularly in combination with another “soft” string instrument, preferably a second lute. Clearly, the new practice did not abruptly replace the older one. Rather, we can assume a long transition period during which both variants coexisted. There is evidence that Schubinger practiced both the older and the newer forms of lute playing. He belonged to an older generation of lutenists under Maximilian, along with Albrecht Morhanns, who was also born around 1460. Morhanns is known to have performed in ensembles. By contrast, the lute intabulations of Adolf Blindhamer, born around 1480 and employed by Maximilian since 1503, testify to the new, soloistic playing of polyphonic pieces.[16] Additionally, during the 1480s and 1490s, and occasionally after 1500, lute duos in Maximilian’s service are documented.[17] The depiction of the Triumphzug titled “Musica süeß Meledey” shows the typical combination of small and large lutes (» I. Ch. “Musica süeß Meledey”: Instrumental Ensembles). Schubinger’s possible involvement in a lute duo might be indicated by the fact that in 1508, he—described as “luytslager vanden keysere” (lutenist of the emperor)—received a payment from the city of Mechelen, alongside “Lenaert luytslager”, who frequently travelled in Maximilian’s entourage and was later at the court of Philip the Handsome and Margaret of Austria.[18]

“Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang” (we have added trombones and cornetts to the singing)

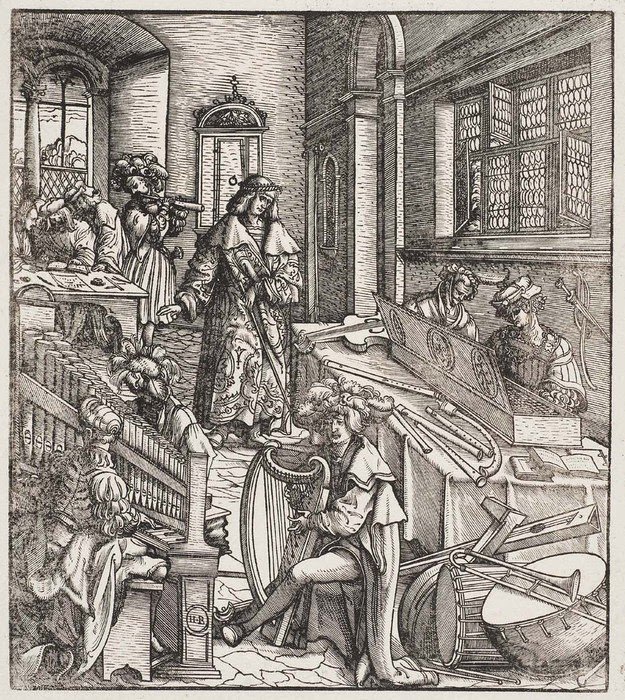

Since the later fifteenth century, courtly and urban alta ensembles expanded to include instruments such as crumhorns, recorders and cornetts.[19] This trend also influenced the court music of Maximilian I, as evidenced by the Triumphzug, which depicted crumhorns and shawms on the music wagons with the motto “Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang” (we have added trombones and cornetts to the singing) (» Fig. Triumphzug wind instruments).[20] One of the most significant and lasting developments in ensemble formation around 1500 was the creation of a new ensemble type: the combination of cornetts and trombones. (» Hörbsp./ audio ♫Optime pastor.) This combination was not only new in itself but also took on a new function by joining the vocal ensemble, particularly in performing sacred vocal polyphony within the liturgy.

The early history of the cornett and the cornett-trombone ensemble cannot be fully reconstructed. However, it is evident that almost all of the earliest sources documenting the combination of singers with cornett and trombone or their use in the liturgy come from the Habsburg courts or their surroundings.[21] These include not only the depiction of the “Musica Canterey” (chapel) in the Triumphzug, Antoine Lalaing’s travel description[22], the reports of mass services during imperial diets, and municipal payment records, but also a remark about the Nuremberg trombonist Johannes Neuschl, who repeatedly worked for Maximilian I between 1502 and 1517 and was praised for “humano concentui tube sonoritatem permiscet”[23] (adding the sound of the tuba [that is, any brass instrument] to the harmony of human voices). It is therefore more than likely that the musicians at the Habsburg courts, including Schubinger, played a leading role in the development of this new practice.

As the sources clearly show, cornettists and trombonists played simultaneously with the singers, accompanying them colla parte or occasionally replacing individual vocalists, so that the respective voice was purely instrumental. (» Hörbsp./ audio ♫ Mater digna Dei.) Additionally, various reports—originating not only from the Habsburg context—suggest that wind ensembles around 1500 also took on other tasks in the liturgy. They could be used for the alternatim performance of liturgical chants, playing instrumental pieces based on the respective chant melody in alternation with the singers, or providing preludes and postludes that introduced or concluded individual chants or longer sections of the liturgical sequence.[24]

Although a group of four to five trombonists can be repeatedly documented at Maximilian’s court since around 1500,[25] it is not assumed that a “full-voiced” ensemble of cornetts and trombones was always formed. Rather, “reduced” ensembles of just one or two wind players are also to be expected, as shown by well-known depictions such as the portrayal of the ensemble with only Schubinger and Steudl in the Triumphzug or the illustration in the music chapter of the Weißkunig (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33 / Fig. Weißkunig fol. 33, in: » I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I), which shows a group of singers with a cornett player in the upper left corner.

The constellation depicted in the Triumphzug is probably not atypical. Several testimonies suggest that wind duos were more widespread in various liturgical and especially secular contexts than the standard four-member alta ensembles around 1500 might suggest. This applies to the musical life in cities, some of which only had two city pipers,[26] as well as to courtly music practice. In addition to payments to wind pairs (occasionally including Schubinger[27]), pictorial sources especially prove the existence of such duos. These include depictions of dance scenes in the tournament book Freydal, commissioned by Maximilian I. While the combination of flute (or fife) and drum dominates, the dancers are also accompanied once each by shawm (or cornett?) and trombone, by flute and trombone, and by two flutes.[28]

Playing in Instrumental Ensembles

In Schubinger’s time, a significant portion of instrumental music was still part of an “oral tradition.” Researchers have now been able to reconstruct quite precisely the methods by which instrumental ensembles spontaneously created polyphonic pieces.[29] The point of departure were existing melodies familiar to the musicians, which depending on the occasion could be a liturgical chant, a song melody, one of the so-called tenores available for dance music, or a single voice extracted from a polyphonic vocal composition. This cantus prius factus was played in the tenor range, from around 1500 increasingly also in the discant. The other instruments provided higher or lower voices, following standardised interval progressions that guaranteed the contrapuntal correctness of the piece while simultaneously enriching the melodic lines with figurative or ornamental, often formulaic, turns. This type of “improvisation” was thus highly determined by guidelines, models, and patterns. Additionally, it is conceivable that the music, especially when played by well-rehearsed ensembles, tended to become fixed through routine and repetition and possibly consisted of more or less fixed pieces reproduced from memory. Therefore, it is somewhat misleading to equate instrumental practice indiscriminately with “improvisation”, as is often done in the literature. Moreover, extemporised ensemble playing was based on the same compositional principles as composed or written vocal music and could lead to elaborate results, especially among professional instrumentalists, which did not fundamentally differ from composed polyphony.

This connection between instrumental practice and vocal composition is particularly relevant in the context of a second area of instrumental music-making. Around the mid-fifteenth century, originally vocal pieces, especially chansons and song settings, but also motets and mass movements, increasingly entered the repertoire of string and wind instrumentalists. A note-for-note reproduction was probably the exception. Instead, adaptations to the technical and tonal conditions of the instruments were to be expected, as well as diminutions (ornamentations) or the addition of new voices to the original setting, using the same or similar procedures as in the spontaneous production of instrumental pieces.[30]

The incorporation of vocal polyphony into the repertoire of instrumental ensembles created the basis for the aforementioned innovation in performance practice around 1500, which also was its immediate continuation: the accompaniment of the vocalists by cornetts and trombones. Whether the wind players also maintained that same flexible handling of the original works, such as adding ornamentation or additional voices, as in purely instrumental realisations, is not directly documented but quite conceivable. Such possibilities are still underused in today’s performance practice.

Textless Compositions

Surviving sources of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, particularly from northern Italy but also from the German-speaking region, transmit a large corpus of pieces in mensural notation but without text. Earlier research tended to view these generally as “instrumental music”. However, many of these pieces have now been identified as chansons, songs, motets, or excerpts from mass settings that were simply notated without text. It has become increasingly clear that notation without text does not necessarily imply an instrumental performance. Rather, there are numerous testimonies to the practice of singing textless notated pieces, either with words (the original text, or a contrafact, transmitted in some other source or reproduced from memory) or without words (by vocalising or solmising).[31]

Thanks to detailed studies of context, transmission, form, and style, a core of works has emerged that were very probably written independently of a text and intended for instrumental ensembles (which did not exclude other forms of performance such as textless singing or intabulation and performance on lute or keyboard instruments).

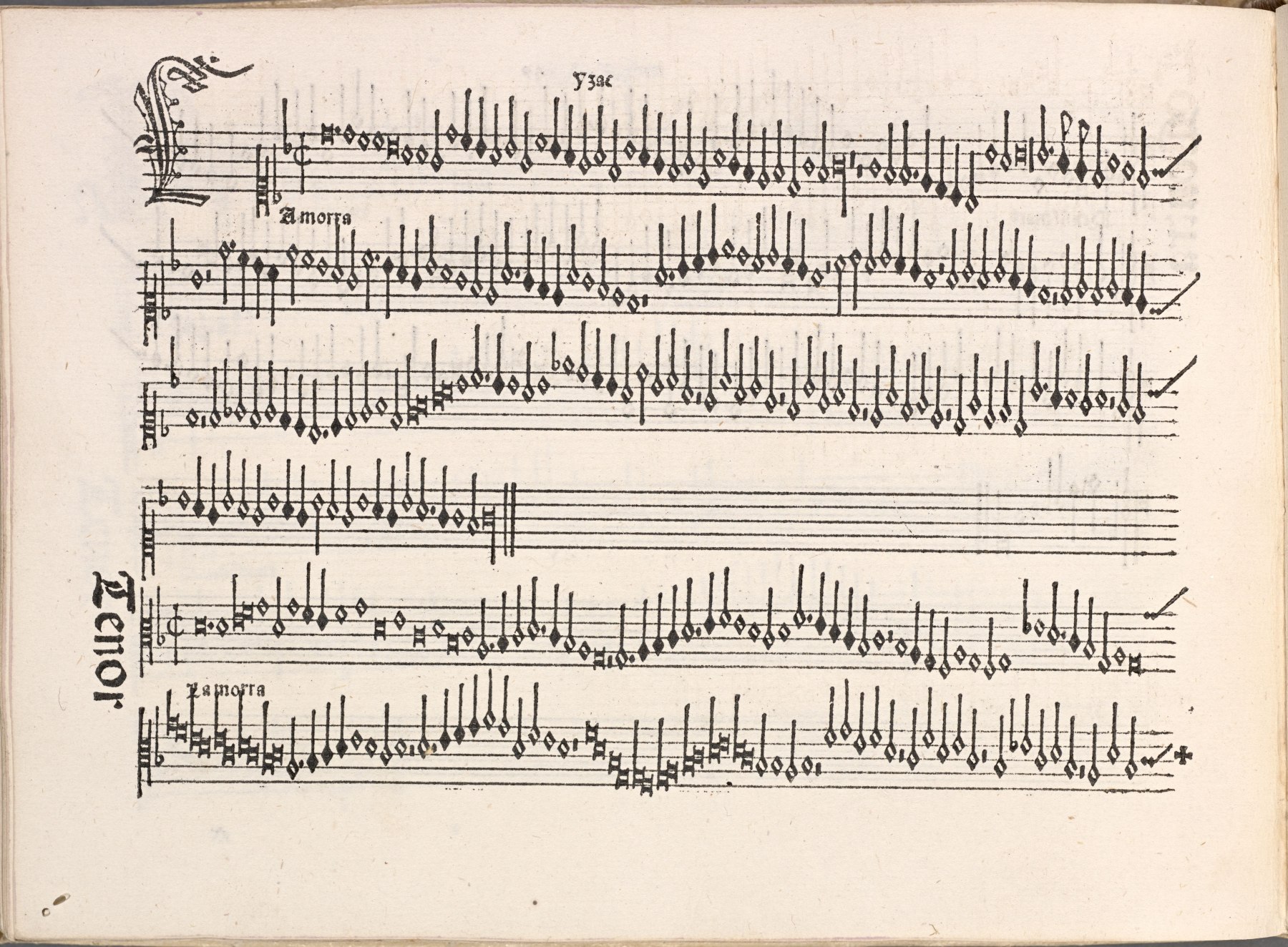

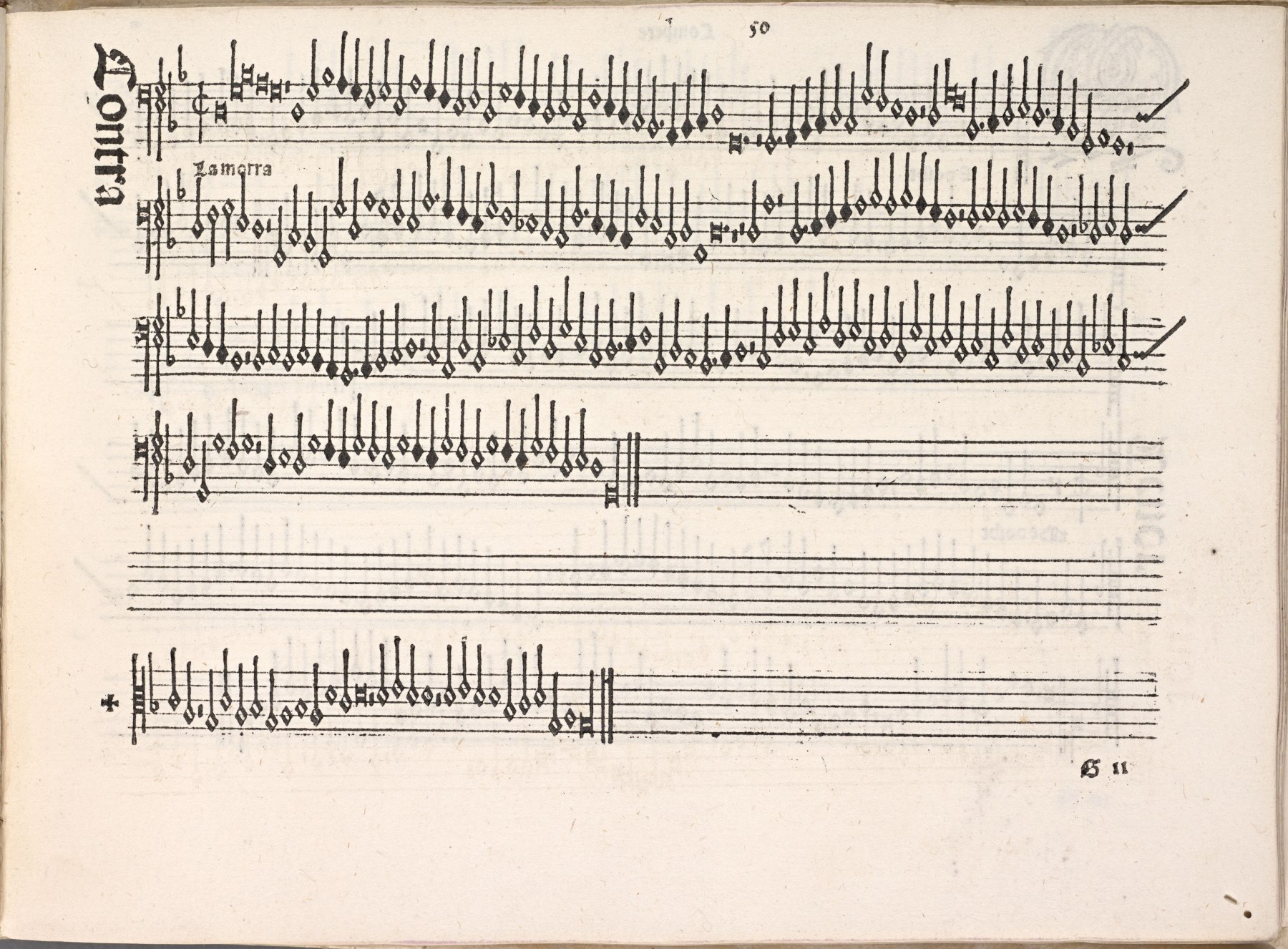

Among these three- or four-part pieces, which include works by the most renowned Franco-Flemish composers of the time such as Josquin, Obrecht, and Isaac, two types can be distinguished: on the one hand, so-called “cantus firmus arrangements”, in which pre-existing melodic material—popular song or dance melodies or individual voices taken from polyphonic chansons—is reworked; on the other hand, so-called “instrumental fantasias”, free of cantus firmus material, including such popular pieces as Johannes Martini’s La martinella and Heinrich Isaac’s La Morra, transmitted in numerous sources.[32]

Isaac’s composition is preserved in more than twenty sources, including Petrucci’s ground-breaking edition of 1501. Titles referring to specific people or “extra-musical” subjects, formed from solmisation syllables, or using abstract musical terms (such as “carmen”) are not uncommon in instrumental fantasias, as a text or cantus firmus was not available for naming. The meaning of the title “La Morra” is uncertain. Suggestions include the Milanese Duke Ludovico Maria Sforza, known as “Il moro”, the popular Italian game of Morra, and the Spanish victory over the Moors at Granada in 1492.

The composition of textless or instrumental ensemble pieces probably began in Central Europe after the mid-fifteenth century before taking hold in Italy somewhat later. Since around 1470, certain composers emerged as specialists in this type of music, notably Johannes Martini, Alexander Agricola and Heinrich Isaac. It is notable that these musicians were active in northern Italian cities like Ferrara and Florence, which were also known for their highly developed instrumental music culture. Therefore, it is plausible that the production of such polyphonic, mensurally notated instrumental pieces was stimulated by encounters with the outstanding instrumental virtuosos of the time, who were also capable of performing composed (vocal) polyphony—a connection directly documented in the case of Heinrich Isaac and Augustin Schubinger (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac).

A South German Humanist Correspondence

On June 8, 1506, Lorenz Beheim, a humanist scholar and cleric who, after a long period in papal service, from 1505 held a canonry at St. Stephen’s in Bamberg, sent a series of musical pieces to the well-known humanist and Nuremberg patrician Willibald Pirckheimer. Pirckheimer had spent many years in Italy for study purposes. He became a member of the city council of his hometown in 1496, and since 1500 belonged to the circle of advisors and confidants of Maximilian I.[33]

The correspondence between the two friends provides insight into the intense exchange of repertoire that took place around 1500 between European regions, between court and city, and also between professional and amateur musicians like Pirckheimer and Beheim.

Lorenz Beheim’s Letter to Willibald Pirckheimer. 1506. Junii 8. Babenbergae

Salve. Hodie lectis litteris tuis statim perquisivi libellos meos musicae et reperi, et ecce tibi mitto in uno quinternione II bassadanzas de Johann Maria et I zelor [sic] amoris Boruni. La prima bassa è una cosa troppo forte, perchè e doppia, et la 2a è simpia. In alio autem quinternione, cuius prima suprascriptio est “Alla bataglia“, è una bona cosa. Reperies caecus et ellas. Deinde la bassadanza de Augustino Trombone, qui est in curia regis Romani, et est satis bona e ligiera. Deinde est alia simplex bassa, quae potest pulsari in organis. Ex his omnibus colligas tibi unam, quae placeat. Et remitte mihi hos quinterniones omnino et expedias. Ego autem pulsavi aliam bassam et tibi etiam eam misissem, nisi tempus fuisset mihi nimis breve ad copiandum; mittam tamen.[34]

(Bamberg, June 8, 1506

Greetings. After reading your letter today, I immediately searched for and found my music books. I am sending you here in a booklet of five leaves two bassedanze by Johann Maria and a “zelor amoris” [Je loe amours] by Boruni. The first bassadanza is quite difficult because it is double, the second is simple.[35] In a second booklet of five leaves [there is] a first piece titled “Alla bataglia”, which is beautiful. You will also find “caecus” [non iudicat de coloribus] and “ellas” [Hélas …] in it; then a bassadanza by Augustin the Trombonist, who is at the court of the Roman king, and it is quite good and light; then another simple bassadanza that can be played on the organ. Choose one piece that you like from all of these. And return these booklets to me completely and quickly. I also played another bassadanza and would have sent it to you as well if I had not had too little time to copy it; I will send it later.)

Three weeks later, Beheim fulfilled his promise and sent additional bassedanze. The note that these were “ad XIII cordas” (for thirteen strings) but easily adaptable “ad XI cordas” (for eleven strings),[36] indicates that Beheim’s shipments consisted of lute pieces or arrangements of pieces for lutes with seven or six courses.

Only Beheim’s letters have survived, not the accompanying music booklets. However, most of the mentioned works are known thanks to a rich transmission in music manuscripts and prints: “Zelor amoris” is undoubtedly the famous and widely arranged chanson Je loe amours by Gilles Binchois,[37] “caecus” the frequently transmitted “instrumental fantasia” Cecus non iudicat de coloribus by Alexander Agricola, “A la battaglia” probably the eponymous song setting by Heinrich Isaac composed in Florence (» Hörbsp.♫ A la battaglia), and “Ellas” one of the numerous Franco-Flemish chansons beginning with “Hélas”, most probably the widely preserved and often arranged Hélas, que pourra by Firminus Caron.

The bassedanze sent by Beheim are unknown. If they are not lost, they might be among the many dances anonymously included in sixteenth-century lute music collections, although a precise identification is impossible. However, the “authors” of the bassedanze can be identified: “Augustino Trombone” is Schubinger, and “Johann Maria” is a lutenist also known as “Johannes Maria Dominici” and “Giovanni Maria Hebreo”, who was active in Florence, Rome and Urbino between 1492 and 1526[38]; he was also in contact with Ulrich and Augustin Schubinger.[39]

Grantley McDonald has considered the possibility that Beheim obtained the pieces by Agricola, Schubinger, and Isaac from Eberhardt Senft, a member of Maximilian’s chapel and like Beheim a cleric in Bamberg (at St. Jakob).[40] It is notable that Beheim refers to Schubinger as “Augustino Trombone”, using his Italian name; he also switches from Latin to Italian elsewhere. All the pieces were either widespread in Italy (this applies to the French chansons as well as to Cecus) and/or composed by musicians active there or originating there. It is thus equally conceivable that Beheim, who had returned to his German homeland from Rome only a few years earlier in 1503, brought the collection back from Italy himself. Regardless of that, Beheim’s booklets, with their mix of chansons, an instrumental fantasia and dances, can be seen as typical of the repertoire used by a professional lutenist like Schubinger around 1500.

Besause of Beheim’s mention of the “bassadanza de Augustino Trombone”, Schubinger is sometimes referred to as a “composer” in the literature. However, it would be a gross simplification to imagine the “composer” Schubinger according to a common modern notion as someone who conceived and notated a piece of music at a desk before it was performed in a second step. Given an instrumental music culture characterised by various transitions and overlaps between orality and literacy, between the use of pre-existing material and the flexible handling of given material, other scenarios are conceivable and even more likely. The starting point could have been a piece originally improvised by Schubinger, which was later notated, not necessarily by him. It is also possible that Schubinger relied on a template (created by whoever and in whatever form) but that his version became widespread and eventually circulated under his name.

Schubinger and the Augsburg Songbook

An impression of Schubinger’s repertoire is provided by a source of great importance for reconstructing the music at the court of Maximilian I: the so-called Augsburg Songbook (D-As Cod. 2° 142a).[41]

The manuscript, created around 1513 in Augsburg or Innsbruck, probably served to fix the music recorded in it (it is not suitable as a performance template due to several characteristics of the notation). According to a marginal note, one of the scribes (who can be assumed to be among the members of the imperial chapel) was connected with Jakob Hurlacher, an Augsburg city piper[42]—not really a surprising circumstance, as Augsburg functioned as a main base for Maximilian’s musicians (» G. Ch. Augsburg with Citizenship).

The manuscript contains a colourful mix of German songs, French chansons, Latin motets, and a small group of dances. The six pieces for three and four voices are all of Italian origin and suitable for an ensemble of shawm, Pommer, crumhorn, or trombones in various combinations.[43] Stylistically, they represent a new type of dance music emerging around 1500, characterised by short, cadentially closed phrases.

With their clear, repetitive structure and relatively simple texture, marked by extensive parallel movements between discantus and tenor, they represent a type of music that professional instrumentalists could easily memorise. Visual sources suggest that dance music ensembles always played without notated music at that time. This integration into the “oral tradition” is reflected in certain notational peculiarities suggesting that the dances in the Augsburg Songbook were recorded by ear rather than from a written template.[44]

Because the connection between the Augsburg Songbook and Maximilian’s chapel remains unclear, and because of a misinterpretation of the marginal note related to Jakob Hurlacher, it has been speculated in the literature that the dances were transmitted from Ulrich Schubinger to Hurlacher and then to the scribe of the source.[45] However, a direct transfer from Augustin Schubinger himself to the imperial court is at least as likely. Through his Florentine past, Schubinger undoubtedly knew a large repertoire of Italian dances. Moreover, Schubinger, who was a colleague of Alexander Agricola in the chapel of Philip the Handsome, could have been responsible in part or exclusively for the transfer of Agricola’s works, which are found in large numbers in the Augsburg Songbook.[46]

Schubinger and the “musica maximilianea”

The specific musical qualities that earned Schubinger his high esteem—whether technical perfection, virtuosic brilliance, musical inventiveness, or a particular sound—cannot be determined with certainty. Contemporary reports about him are too general, and we know too little about the criteria for judging aesthetic qualities in music at that time. However, there are some clues helping to clarify Schubinger’s “value” to Maximilian I and the music at his court.

As far as their origins can be traced, the musicians whom Maximilian recruited from the mid-1490s onwards, with exceptions such as Heinrich Isaac, came from the Austrian territories or the southern German-speaking region. In this respect, Schubinger’s engagement fits into the overall picture. One characteristic—which he shared with the Fleming Isaac—distinguished him from most of his colleagues: his international experience, acquired during his years of activity in Italy and Burgundy, and possibly also during travels through Spain, France Savoy and elsewhere.

It can therefore be assumed that Schubinger had extensive knowledge of musical repertoires and practices from many parts of Europe and was integrated into transregional personal networks. That this benefited the music at Maximilian I’s court, is not only likely in principle but may also be shown in concrete detail. As mentioned, Schubinger probably introduced Isaac to the imperial chapel (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac) and was the source for the dances and Agricola’s pieces in the Augsburg Songbook (» Kap. Schubinger und das Augsburger Liederbuch). The same could apply to the works of Pierre de La Rue, another colleague from the time with Philip the Handsome, which are found in sources containing Maximilian’s repertoire (A-Wn Mus.Hs. 18810 and D-Mu, 8°Cod. ms. 328–331).[47] Schubinger may also have played a role in the reception of the lira da braccio (» Instrumentenmuseum. Lira da braccio) at Maximilian’s court.[48]

Schubinger’s familiarity with Italian music and culture may have brought another advantage: Bianca Maria Sforza, Maximilian’s second wife from 1493, tried to maintain her connection to her homeland even in Austria. She surrounded herself with numerous Italian ladies and servants, engaged an Italian solo singer, practised Italian dances, and had a clavichord sent from Mantua.[49] Schubinger’s experiences from his time in Florence could have been welcome in this regard as well.

Beyond these individual aspects, Schubinger’s significance must be seen on a general level, in relation to the overall profile of Maximilian’s music. Instrumental music was evidently highly valued at Maximilian’s court.[50] Remarkable is the density of first-rate players, including Schubinger, Paul Hofhaimer, Hans Steudl and Hans Neuschl. Equally notable is the integration of instrumental music into the practice of the vocal chapel, manifested in the inclusion of wind players in the performing ensemble and the practice of the so-called missae ad organum, in which sections of vocal polyphony and organ versets alternated (» D. Kap. Isaac als Schlüsselfigur: choralbasierte Propriums- und Ordinariumszyklen). That instrumental music was among the special highlights of Maximilian’s court music is evident in the Triumphzug (» I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I). Four of the five musician wagons are occupied solely by instrumentalists or instrumental ensembles, and even on the fifth, the choir wagon, the instrumental part is emphasised by the images of Schubinger and Steudl and, even more clearly, by the text program. Additionally, all musicians named in the Triumphzug are instrumentalists.[51] All this leads to the conclusion that Schubinger, as one of the most brilliant instrumentalists of his time, played a key role in the musical culture at Maximilian’s court.

[1] From Schubinger’s service record of 1514 ( » Abb. Schubingers Dienstrevers 1514).

[2] See for example D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 89 (1495), fol. 17r; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 17r; Vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v.

[3] Grassl 1999, 208, referring to Wessely 1956, 130–134. See also the documents from 1514, according to which Schubinger was employed as a “Posaunist” (trombonist), although at that time he also, if not primarily, appeared as a cornettist.

[4] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 80 (1487), fol. 65r.

[5] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 82 (1489), fol. 66r; Vol. 84 (1490), fol. 68r; Vol. 89 (1495) [no fol.]; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 90r. Diettel also distinguished himself from the other city pipers by occasionally receiving a slightly higher salary (40 or 44 fl. instead of the usual 36 fl.).

[6] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 81 (1488), fol. 16r.

[7] Cf. McGee 1999, 731–732; McGee 2008, 166–168.

[8] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 55 (1457), fol. 112v, online: https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-03uw/1.

[9] McGee 2000, 215–216.

[11] Grassl 2019, 223 and 231–234.

[12] Polk 1994a, 210.

[13] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r; V132–41291, (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1511/1512) fol. 209v; Protocol of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091); D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 617v: “Item ij gulden dem Augustin K mt lautenisst zu Juliane anno 1517”.

[14] See Polk 1989a, 496, 500, and 502; McGee 2000, 215; Prizer 1981, 163; further examples in Polk 1989c, 526–527, 542–543; Polk 1990, 196–197; McGee 2005, 149–150; McGee 2008, 210–212.

[15] Although polyphonic lute playing was possible to some extent with plectrum technique. See Lewon 2007. Cf. » Instrumentenmuseum Laute.

[17] » I. Ch. “Musica Lauten und Rybeben”; Nedden 1932/1933, 26–27; Ernst 1945, 222–223; Polk 1992b, 86; Polk 1994b, 407; Schwindt 2018c, 275–276.

[18] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r. For Lenaert (or “Lionhardt”) see the references in Polk 1992b, 86–87; Polk 2001a, 93–94; Polk 2005a, 64 and 66.

[19] Polk 1992a, 73–75; Polk 1987, 180; specifically for Nuremberg cf. Green 2005, 13.

[20] Depiction of the choir wagon in the Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.).

[21] See the compilation of evidence in Grassl 2019, 230–246.

[22] See, in addition to the evidence mentioned in » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 57, 58, 61, also the minutes of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris. Als derselb Augustini etlich tag im chor zur orgel vnd den sengern uff dem zingken geblausen hat, ist capitulariter conclusum, im zu erunge 2 fl. zeschencken” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091).

[23] Cochlaeus 1512, 90–91.

[24] Grassl 2017, 347–349 and 357–358; Grassl 2019, 217–221 and 227–228.

[25] Nedden 1932/1933, 28; Wessely 1956, 85, 88, 101–103, and 108–111; Polk 1992b, 86. Cf. in particular the “collective” or “group entries” in: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28r: “Item x guldin Ko mayt. Busanern dero fünffe”; Vol. 98 (1504), fol. 26r: “It. viij gulden Jörigen Holland, Jorigen Eyselin, Hannsen Stevdlin vnd Vlrich Vellen Kö. mayt. Busaunern”.

[26] Polk 1992a, 109; Green 2011, 20.

[27] See the entries in the Nördlingen account books of 1506 and 1507 (» Abb. Zahlung der Stadt Nördlingen an Schubinger, 8. Juni 1506), as well as » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 67.

[28] Henning 1987, 87 (plate 183), 90 (plate 211), 94 (plate 255).

[29] Fundamentally Polk 1992a, 169–213; see also Gilbert 2005; Neumeier 2015, 273–290.

[30] For an overview of instrumental music-making around 1500 see Coelho/Polk 2016, insb. 189–225; Grassl 2013.

[32] Cf. from the extensive literature on this repertoire only Polk 1997; Strohm 1992; Jickeli 1996; Banks 2006.

[33] For Pirckheimer’s biography see: http://www.pirckheimer-gesellschaft.de/html/will_car.html.

[34] Edition in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 371.

[35] This could refer to the distinction between two-part and one-part bassedanze (in the terminology of contemporary French dance literature: basses danses mineurs and majeurs).

[36] Letter of June 29, 1506, edited in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 380. See also Meyer 1981, 62–64 on this correspondence.

[37] Nothing more precise can be determined about “Boruni”, the arranger, i.e., probably the intabulator of Binchois’ composition. Perhaps he was an older relative of the Milanese lutenist Pietro Paolo Borrono, born around 1490 and renowned in the mid-sixteenth century.

[39] This emerges from a remark in Ulrich’s letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac), stating that Ulrich had waited in vain for his brother and “Zoani Maria che suona el liuto” in Ferrara.

[40] McDonald 2019, 13–14.

[41] See especially Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 97–101; Schwindt 2018c, 542–545; see also Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 137–150; » B. Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst; » D. Zur musikalischen Quellenlage.

[42] This was either Jakob Hurlacher the Elder, who served as an Augsburg city piper from 1495 to 1530 (not just from 1508, as regularly claimed in the literature; see the entries in D-Asa Baumeisterbücher), or Jakob Hurlacher the Younger, who was a member of the Augsburg wind ensemble from 1502 to 1506 and from 1509 to 1517.

[43] See in detail Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 151–154; Neumeier 2015, 252–254.

[44] Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 150.

[45] Polk 1991, 158; see also Filocamo 2009. Consequently, Polk’s speculation that the “Mantüane[r] dantz” could be identical to one of the bassedanze sent by Beheim (cf. » H. Ch. A South German Humanist Correspondence) and therefore Schubinger or Giovanni Maria Ebreo its “composer” is purely speculative.

[46] Schwindt 2018c, 280.

[47] Schwindt 2018c, 280; see also Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 184.

[48] Schwindt 2018c, 120–124.

[49] Unterholzner 2015, especially. 79–89, 96–98; Schwindt 2018c, 73–76.

[50] Cf. Lütteken 2010 LIT, 20–21; Polk 2001b; Schwindt 2018c, 20–24.

[51] Besides Schubinger, these include the organist Paul Hofhaimer, the lutenist Albrecht Morhanns, the trombonists Hans Neuschel and Hans Steudl, and the piper Anton Dornstetter. See the relevant image program texts in Schestag 1883, 155 and 158–160.

Recommended Citation:

Markus Grassl: „Instrumentale Musikpraxis im Lebensbereich Augustin Schubingers (ca. 1460–1531/32)“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentale-musikpraxis-im-lebensbereich-augustin-schubingers-ca-1460-153132> (2023).

![Notenbsp. Mantüane[r] dantz Notenbsp. Mantüane[r] dantz](https://musical-life.net/files/styles/embedded/public/18._mantuaner_dantz.png?itok=0ZOgK-C1)