Textless Compositions

Surviving sources of the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, particularly from northern Italy but also from the German-speaking region, transmit a large corpus of pieces in mensural notation but without text. Earlier research tended to view these generally as “instrumental music”. However, many of these pieces have now been identified as chansons, songs, motets, or excerpts from mass settings that were simply notated without text. It has become increasingly clear that notation without text does not necessarily imply an instrumental performance. Rather, there are numerous testimonies to the practice of singing textless notated pieces, either with words (the original text, or a contrafact, transmitted in some other source or reproduced from memory) or without words (by vocalising or solmising).[31]

Thanks to detailed studies of context, transmission, form, and style, a core of works has emerged that were very probably written independently of a text and intended for instrumental ensembles (which did not exclude other forms of performance such as textless singing or intabulation and performance on lute or keyboard instruments).

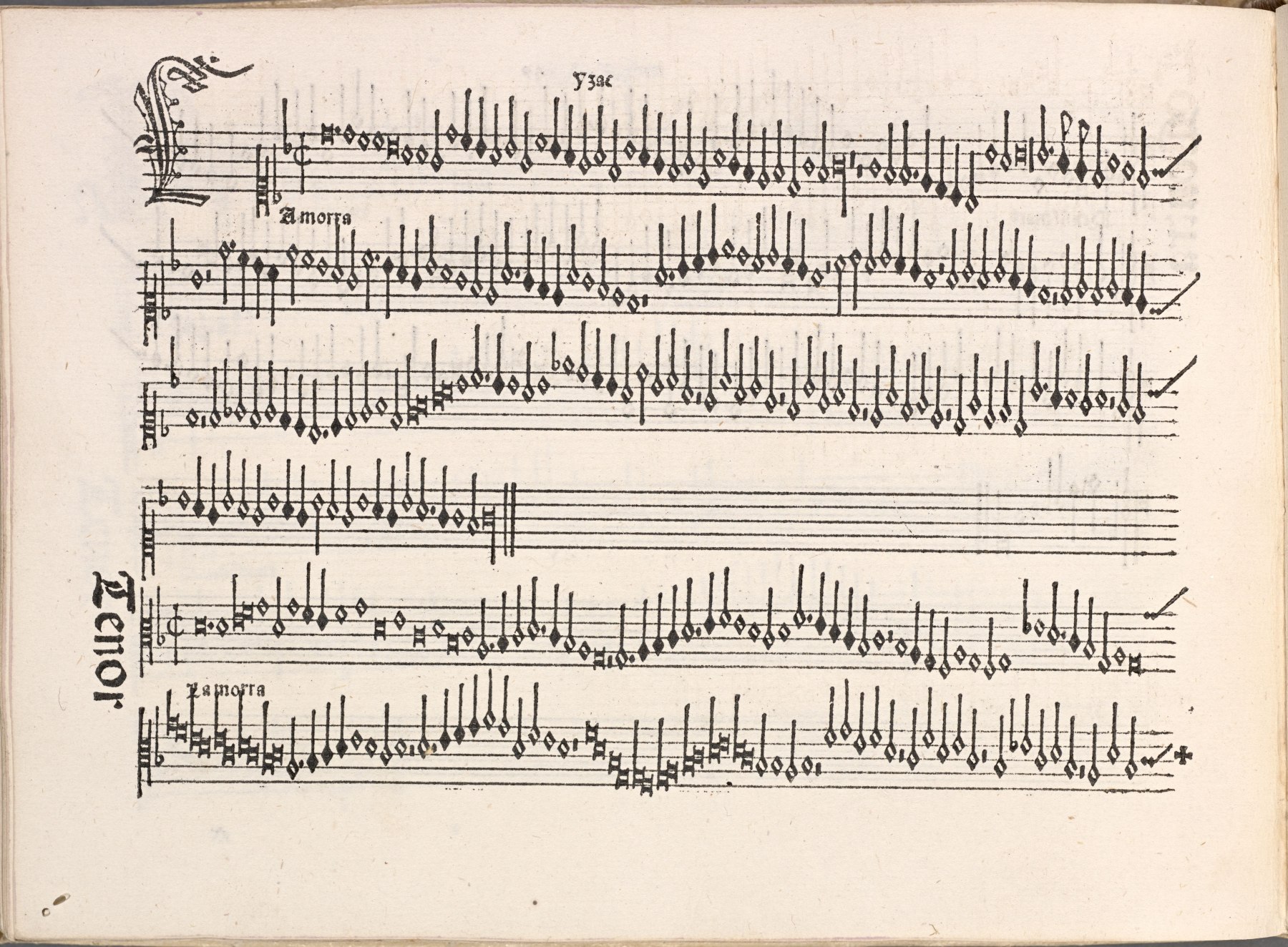

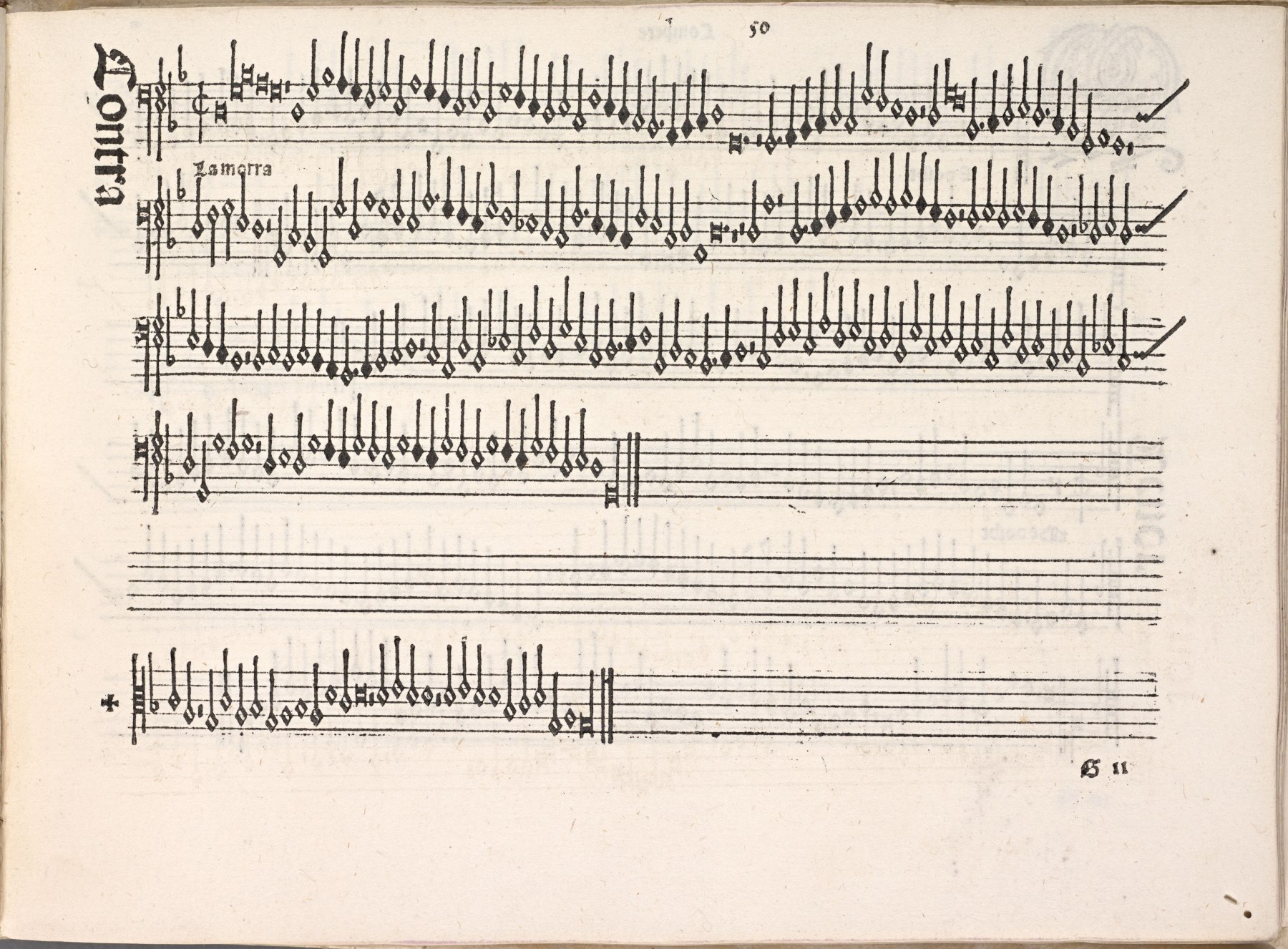

Among these three- or four-part pieces, which include works by the most renowned Franco-Flemish composers of the time such as Josquin, Obrecht, and Isaac, two types can be distinguished: on the one hand, so-called “cantus firmus arrangements”, in which pre-existing melodic material—popular song or dance melodies or individual voices taken from polyphonic chansons—is reworked; on the other hand, so-called “instrumental fantasias”, free of cantus firmus material, including such popular pieces as Johannes Martini’s La martinella and Heinrich Isaac’s La Morra, transmitted in numerous sources.[32]

Isaac’s composition is preserved in more than twenty sources, including Petrucci’s ground-breaking edition of 1501. Titles referring to specific people or “extra-musical” subjects, formed from solmisation syllables, or using abstract musical terms (such as “carmen”) are not uncommon in instrumental fantasias, as a text or cantus firmus was not available for naming. The meaning of the title “La Morra” is uncertain. Suggestions include the Milanese Duke Ludovico Maria Sforza, known as “Il moro”, the popular Italian game of Morra, and the Spanish victory over the Moors at Granada in 1492.

The composition of textless or instrumental ensemble pieces probably began in Central Europe after the mid-fifteenth century before taking hold in Italy somewhat later. Since around 1470, certain composers emerged as specialists in this type of music, notably Johannes Martini, Alexander Agricola and Heinrich Isaac. It is notable that these musicians were active in northern Italian cities like Ferrara and Florence, which were also known for their highly developed instrumental music culture. Therefore, it is plausible that the production of such polyphonic, mensurally notated instrumental pieces was stimulated by encounters with the outstanding instrumental virtuosos of the time, who were also capable of performing composed (vocal) polyphony—a connection directly documented in the case of Heinrich Isaac and Augustin Schubinger (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac).

[32] Cf. from the extensive literature on this repertoire only Polk 1997; Strohm 1992; Jickeli 1996; Banks 2006.

[1] From Schubinger’s service record of 1514 ( » Abb. Schubingers Dienstrevers 1514).

[2] See for example D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 89 (1495), fol. 17r; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 17r; Vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v.

[3] Grassl 1999, 208, referring to Wessely 1956, 130–134. See also the documents from 1514, according to which Schubinger was employed as a “Posaunist” (trombonist), although at that time he also, if not primarily, appeared as a cornettist.

[4] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 80 (1487), fol. 65r.

[5] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 82 (1489), fol. 66r; Vol. 84 (1490), fol. 68r; Vol. 89 (1495) [no fol.]; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 90r. Diettel also distinguished himself from the other city pipers by occasionally receiving a slightly higher salary (40 or 44 fl. instead of the usual 36 fl.).

[6] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 81 (1488), fol. 16r.

[7] Cf. McGee 1999, 731–732; McGee 2008, 166–168.

[8] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 55 (1457), fol. 112v, online: https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-03uw/1.

[9] McGee 2000, 215–216.

[11] Grassl 2019, 223 and 231–234.

[12] Polk 1994a, 210.

[13] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r; V132–41291, (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1511/1512) fol. 209v; Protocol of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091); D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 617v: “Item ij gulden dem Augustin K mt lautenisst zu Juliane anno 1517”.

[14] See Polk 1989a, 496, 500, and 502; McGee 2000, 215; Prizer 1981, 163; further examples in Polk 1989c, 526–527, 542–543; Polk 1990, 196–197; McGee 2005, 149–150; McGee 2008, 210–212.

[15] Although polyphonic lute playing was possible to some extent with plectrum technique. See Lewon 2007. Cf. » Instrumentenmuseum Laute.

[17] » I. Ch. “Musica Lauten und Rybeben”; Nedden 1932/1933, 26–27; Ernst 1945, 222–223; Polk 1992b, 86; Polk 1994b, 407; Schwindt 2018c, 275–276.

[18] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r. For Lenaert (or “Lionhardt”) see the references in Polk 1992b, 86–87; Polk 2001a, 93–94; Polk 2005a, 64 and 66.

[19] Polk 1992a, 73–75; Polk 1987, 180; specifically for Nuremberg cf. Green 2005, 13.

[20] Depiction of the choir wagon in the Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.).

[21] See the compilation of evidence in Grassl 2019, 230–246.

[22] See, in addition to the evidence mentioned in » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 57, 58, 61, also the minutes of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris. Als derselb Augustini etlich tag im chor zur orgel vnd den sengern uff dem zingken geblausen hat, ist capitulariter conclusum, im zu erunge 2 fl. zeschencken” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091).

[23] Cochlaeus 1512, 90–91.

[24] Grassl 2017, 347–349 and 357–358; Grassl 2019, 217–221 and 227–228.

[25] Nedden 1932/1933, 28; Wessely 1956, 85, 88, 101–103, and 108–111; Polk 1992b, 86. Cf. in particular the “collective” or “group entries” in: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28r: “Item x guldin Ko mayt. Busanern dero fünffe”; Vol. 98 (1504), fol. 26r: “It. viij gulden Jörigen Holland, Jorigen Eyselin, Hannsen Stevdlin vnd Vlrich Vellen Kö. mayt. Busaunern”.

[26] Polk 1992a, 109; Green 2011, 20.

[27] See the entries in the Nördlingen account books of 1506 and 1507 (» Abb. Zahlung der Stadt Nördlingen an Schubinger, 8. Juni 1506), as well as » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 67.

[28] Henning 1987, 87 (plate 183), 90 (plate 211), 94 (plate 255).

[29] Fundamentally Polk 1992a, 169–213; see also Gilbert 2005; Neumeier 2015, 273–290.

[30] For an overview of instrumental music-making around 1500 see Coelho/Polk 2016, insb. 189–225; Grassl 2013.

[32] Cf. from the extensive literature on this repertoire only Polk 1997; Strohm 1992; Jickeli 1996; Banks 2006.

[33] For Pirckheimer’s biography see: http://www.pirckheimer-gesellschaft.de/html/will_car.html.

[34] Edition in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 371.

[35] This could refer to the distinction between two-part and one-part bassedanze (in the terminology of contemporary French dance literature: basses danses mineurs and majeurs).

[36] Letter of June 29, 1506, edited in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 380. See also Meyer 1981, 62–64 on this correspondence.

[37] Nothing more precise can be determined about “Boruni”, the arranger, i.e., probably the intabulator of Binchois’ composition. Perhaps he was an older relative of the Milanese lutenist Pietro Paolo Borrono, born around 1490 and renowned in the mid-sixteenth century.

[39] This emerges from a remark in Ulrich’s letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac), stating that Ulrich had waited in vain for his brother and “Zoani Maria che suona el liuto” in Ferrara.

[40] McDonald 2019, 13–14.

[41] See especially Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 97–101; Schwindt 2018c, 542–545; see also Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 137–150; » B. Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst; » D. Zur musikalischen Quellenlage.

[42] This was either Jakob Hurlacher the Elder, who served as an Augsburg city piper from 1495 to 1530 (not just from 1508, as regularly claimed in the literature; see the entries in D-Asa Baumeisterbücher), or Jakob Hurlacher the Younger, who was a member of the Augsburg wind ensemble from 1502 to 1506 and from 1509 to 1517.

[43] See in detail Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 151–154; Neumeier 2015, 252–254.

[44] Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 150.

[45] Polk 1991, 158; see also Filocamo 2009. Consequently, Polk’s speculation that the “Mantüane[r] dantz” could be identical to one of the bassedanze sent by Beheim (cf. » H. Ch. A South German Humanist Correspondence) and therefore Schubinger or Giovanni Maria Ebreo its “composer” is purely speculative.

[46] Schwindt 2018c, 280.

[47] Schwindt 2018c, 280; see also Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 184.

[48] Schwindt 2018c, 120–124.

[49] Unterholzner 2015, especially. 79–89, 96–98; Schwindt 2018c, 73–76.

[50] Cf. Lütteken 2010 LIT, 20–21; Polk 2001b; Schwindt 2018c, 20–24.

[51] Besides Schubinger, these include the organist Paul Hofhaimer, the lutenist Albrecht Morhanns, the trombonists Hans Neuschel and Hans Steudl, and the piper Anton Dornstetter. See the relevant image program texts in Schestag 1883, 155 and 158–160.

Recommended Citation:

Markus Grassl: „Instrumentale Musikpraxis im Lebensbereich Augustin Schubingers (ca. 1460–1531/32)“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentale-musikpraxis-im-lebensbereich-augustin-schubingers-ca-1460-153132> (2023).