Genres and composers in the Leopold codex

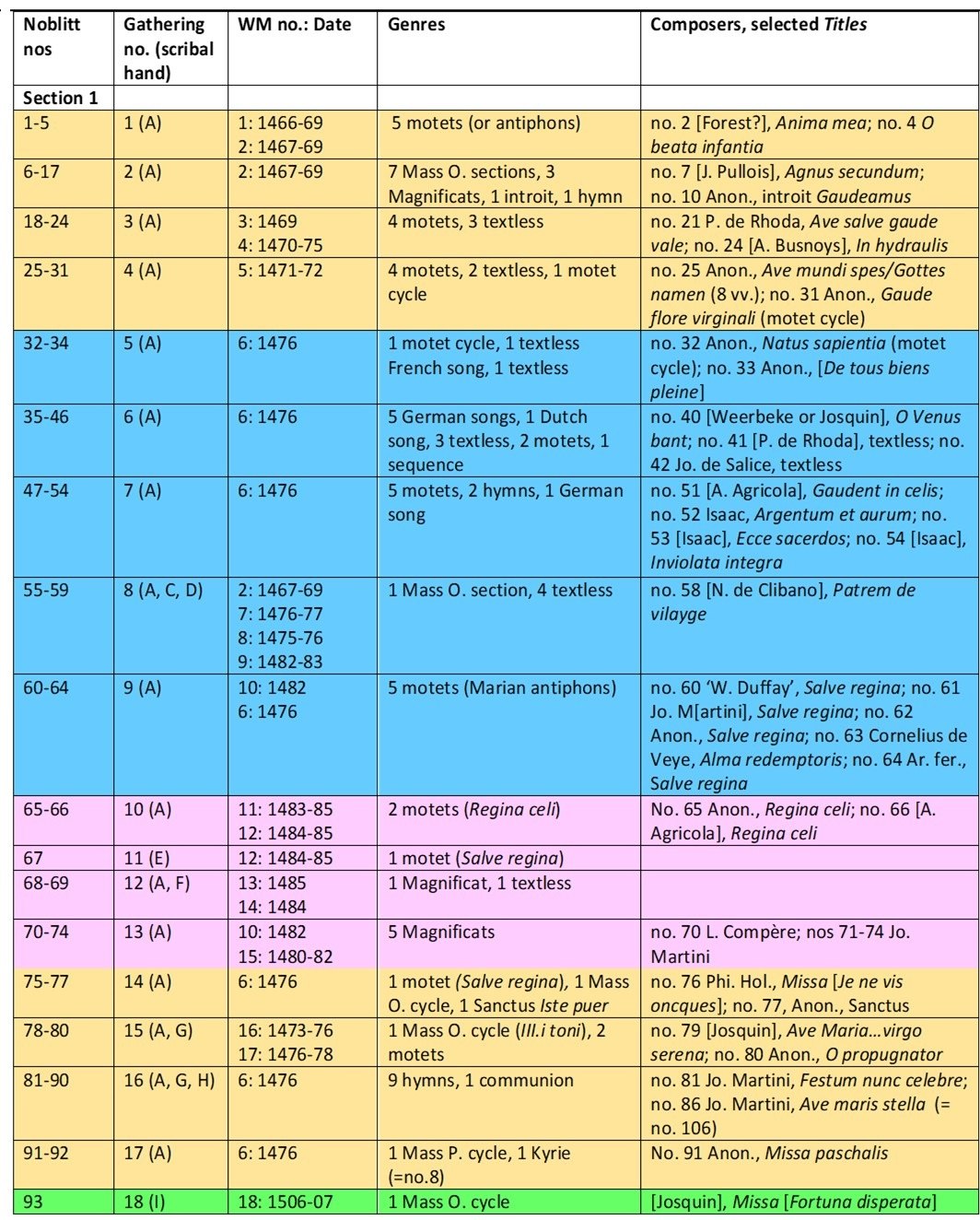

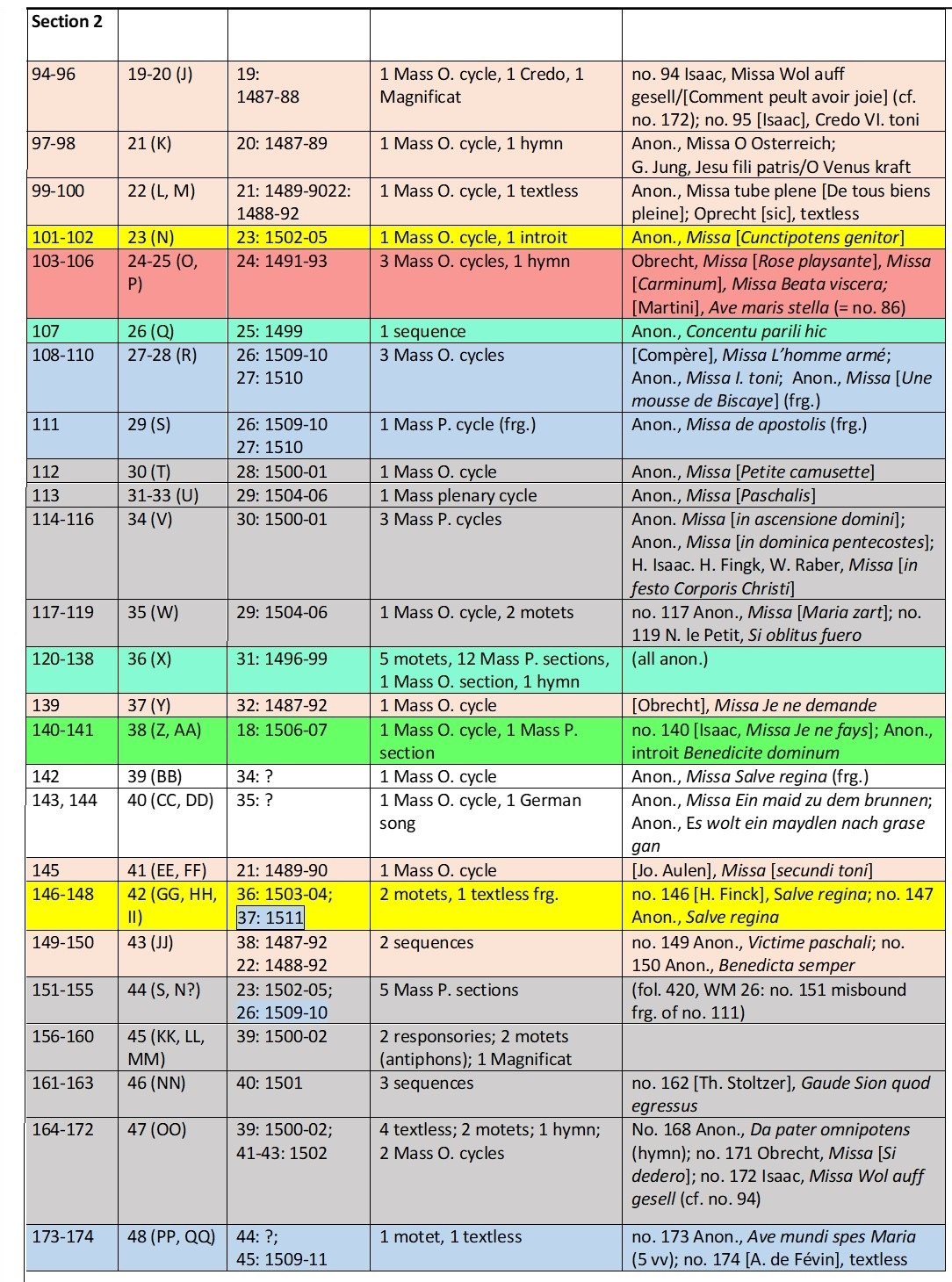

Most of the music in the Leopold codex is sacred and Latin-texted, though a few secular works are also present. The codex contains three plenary Mass cycles (consisting of sections of both the Ordinary and the Proper of the Mass; a fragment of one of these is also copied elsewhere in the codex) and 21 Mass Ordinary cycles (one of which is copied twice), along with 11 independent Mass Ordinary sections (one copied twice), two motet cycles (of which each item functioned as a substitute for a Mass Ordinary section), three cycles of polyphonic Mass Propers (in addition to those incorporated in the plenary cycles already mentioned) and 29 independent Mass Proper items. 44 pieces are motets or antiphon settings, 14 are Vespers hymns (one copied twice), 11 are Magnificat settings, and two are settings of responsories There are also nine secular pieces (seven German, one Dutch and one textless but derived from a French polyphonic song) and 21 untitled and textless works, mostly of the motet type. Several works are fragments, either because they were left incomplete by the scribe or because pages are missing from the manuscript; some fragments only repeat music copied elsewhere. (See » Abb. Synopsis of the Leopold codex.)

In only 23 cases did the copyist attach a composer’s name, the remainder being copied anonymously. For another 28 works the composers can be ascertained from external concordances. Thus more than two thirds of the compositions remain anonymous to us. Of the 22 identifiable composers, the most prominent are Henricus Isaac with seven works (four of which are attributed in the manuscript), Johannes Martini also with seven (all attributed) and Jacob Obrecht with six (three attributed). Setting aside modern tentative ascriptions (for example to Paulus de Rhoda),[14] no other named composer was responsible for more than two pieces at most. This is the case, remarkably, with composers as notable as Josquin Desprez, Loyset Compère, Gaspar van Weerbeke, Alexander Agricola, Heinrich Finck and Thomas Stoltzer; among the remaining identified authors there are a few more foreigners (Jean Pullois, Antoine Busnoys, ‘Ar. Fer.’, Phi. Hol., Ninot le Petit, Nicasius de Clibano, Antoine de Févin) and lesser-known musicians perhaps of Central European origin (Aulen, G. Jung, W. Raber, Paulus de Rhoda, Cornelius de Veye, Jo. de Salice). Admittedly, compositions by the most renowned masters of the period – usually hailing from the Franco-Flemish region – may still be hidden among the anonyma (the anonymous Missa Je ne fays, no. 140, has only recently been identified as Isaac’s):[15] but we must assume that many other local or regional musicians contributed to the collection.

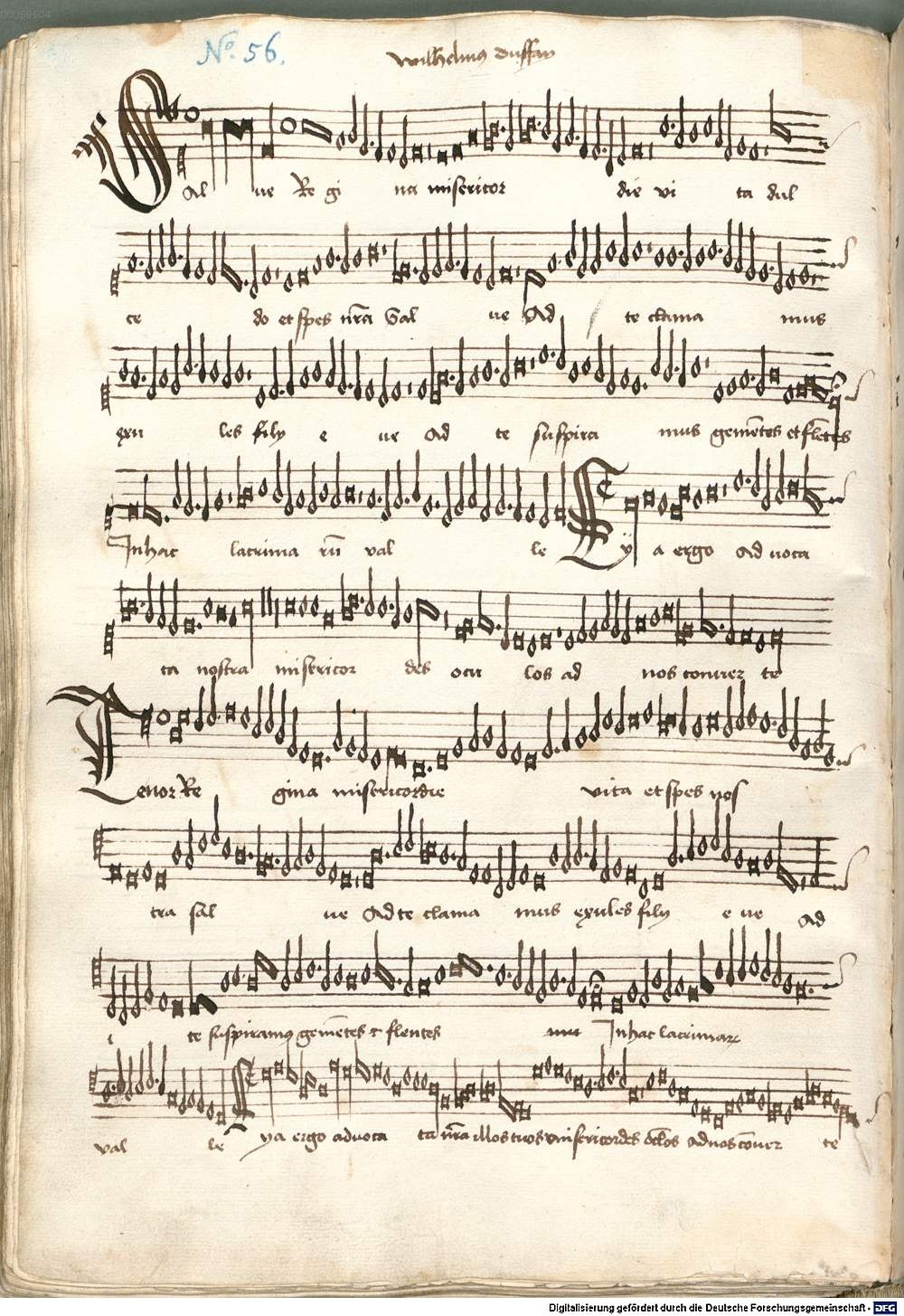

Only two attributions in the manuscript seem erroneous. The name of ‘Josquin’ appears above the much-circulated Missa L’homme armé by Loyset Compère (no. 108). A substantial four-voice Salve regina (no. 60) bears the name ‘Wilhelmus duffay’ (» Abb. Salve regina ‘Wilhelmus duffay’), an attribution that has been challenged.[16]

The setting is stylistically quite unlike Guillaume Du Fay’s known antiphon settings, but seems to belong to a Franco-Flemish composer of the mid-fifteenth century.[17] Only Compère, Isaac and Martini can be associated with music found in both sections of the codex. Both works by Josquin, the immortal Ave Maria…virgo serena and the Missa Fortuna desperata, are present in the first section, but only because the Mass cycle was appended to the end of the first section long after its completion; it was copied c.1506-07 by a single hand (‘I’) not seen elsewhere in the codex, and is contained within a gathering of its own, as is typical for the organisation of the second section.[18]

[16] Dèzes 1927; see also Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 369.

[17] The work is later anonymously transmitted in Librone 1 of the Gaffurius-Codices of Milan (I-MD 2269). Rifkin 2003, 255, thinks that it might be by Antoine Busnoys.

[18] Rumbold 2018, 319-22 describes the copy of the Sanctus and Agnus Dei in detail, with facsimile.

[1] Colour images of the manuscript are available at https://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0005/bsb00059604/images/.

[2] Some 34 hands can be distinguished in the second section of the manuscript alone; one of these (hand ‘Y’, fols 370r– 379v) also occurs in the manuscript D-B Mus. Ms. 40021 (fols 253r–254v).

[3] Noblitt 1987-96, I, viii; synopsis of foliations in IV, 313-14.

[5] Noblitt 1968, 1974, 1987, 1997 (etc.). For other recent research, see Strohm 1993, 516-23; Rifkin 2003, Rumbold 2018.

[6] See, for example, Josquin Desprez, Missa Fortuna desperata (fols 172r-178r), recorded in 2001 by the Clerks’ Group, dir. Edward Wickham (ASV label, catalogue no. GAU 220); in 2009 by the Tallis Scholars, dir. Peter Phillips (Gimell label, catalogue no. 42); and in 2018 by Biscantor! Métamorphoses (Ar-Re-Se label, catalogue no. AR 20181). The second Agnus Dei of Isaac’s Missa Wol auff gesell/Comment peult avoir joye (fols 179r-196r and 456v-463v) was recorded by Capella Alamire and the Alamire Consort, dir. Peter Urqhuart, CD Music of Pierrequin de Thérache (Centaur label, catalogue no. CRC3282), track 10. Kyrie of the anonymous Missa O Österreich (fols 205v-213r): Ensemble Rosarum Flores, CD Global Player Maximilian: Musikalisches Networking um 1500 (Musikmuseum label, catalogue no. 13042), track 1. Obrecht’s Missa Si dedero (fols 449v-456r): ANS Chorus, dir. János Bali (Hungaroton label, catalogue no. HCD 31946). The anonymous motets Ave mundi spes/Gottes namen (fols 29v-30r) and O propugnator miserorum (fols 148v-150r): Stimmwerck, SACD Flos virginum: Motets of the 15th Century (CPO label, catalogue no. 7779372), tracks 8 and 6, respectively. Isaac’s motet Argentum et aurum (fols 72v-73r) and the German songs So stee ich hie auff diser erd, Ich sachs ains mals, Gespile, liebe gespile gut, Es sassen höld in ainer stuben (fols 51v-53r): Ensemble Leones, CD Argentum et aurum: Musical Treasures from the Early Habsburg Renaissance (Naxos label, catalogue no. 8.573346), tracks 1, 16, 22, 20 and 21, respectively.

[7] It is not to be confused with the Hofkirche, adjacent to the Hofburg, which was completed in 1553 and contains Maximilian’s cenotaph.

[8] » I. Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck (Helen Coffey).

[9] Fässler 1975.

[10] Fässler 1975, 32, from Tiroler Landesarchiv (TLA) Innsbruck, Raitbücher der tirolischen Kammer, 1511, vol 56, fol 77v, vol 56, fol 290v.

[12] The city archives of Innsbruck (Stadtarchiv, Register, p. 43), mention a ‘Veit schulmaister’ in 1498.

[16] Dèzes 1927; see also Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 369.

[17] The work is later anonymously transmitted in Librone 1 of the Gaffurius-Codices of Milan (I-MD 2269). Rifkin 2003, 255, thinks that it might be by Antoine Busnoys.

[18] Rumbold 2018, 319-22 describes the copy of the Sanctus and Agnus Dei in detail, with facsimile.

[19] For the distribution of the music in the manuscript see Rumbold 2018, with a full inventory.

[20] For details, see Rumbold 2018.

[21] No. 55, for example, is a textless piece written on the two inner sides of a bifolio (fol. 75/84), which was then wrapped round an existing gathering (8), so that the two sides could no longer be read simultaneously. See Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 344, where the last sentence must read ‘so daß eine Aufführung aus dem Ms. unwahrscheinlich ist’.

[23] Noblitt 1968, Rifkin 2003. The actual ‘motetti missales’ of Milan (1470s and later) are not copied here.

[24] » Hörbsp. ♫ for all five songs.

[25] ‘Tannhauser, ihr seid mir lieb’ (Venus addressing Tannhäuser) is a stanza of the ‘Tannhäuserlied’ (Nun will ich aber heben an), printed in Nuremberg, 1515; the Leopold codex is its earliest known source.

[26] See » A. Kap. Der Prozessionshymnus (Stefan Engels): » J. Kap. Passions- und Osterfeierlichkeiten (Andrea Horz); » Notenbsp. O du armer Judas.

[27] On this work, see Staehelin 1977, 148-50, 205.

[28] Noblitt 1992 calls this a Missa in tempore belli; see also » D. SL O Österreich. Page layout of the Agnus Dei described in Rumbold 2018, 322-23.

[29] Steinegger 1954. Further on traditions of the church, see » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck.

[30] Page layout described in Rumbold 2018, 329-34.

[32] » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; » I. Instrumentalkünstler (Martin Kirnbauer).

[34] See Noblitt 1974 (with table of watermarks, p. 39); Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 315-40.

[35] On the methodology, see also Strohm 1983, Rifkin 2003. Watermark dating along these lines has also been applied to the Trent codices (» K. Kap. Die Datierung) and the St Emmeram codex (Strohm 1983, Rumbold-Wright 2006, 14-19).

[36] WM 4, 9 and 10 deviate from the chronology, but these papers are only individual bifolios (26-27, 75/84, 85/98), added to already existing gatherings. Gathering 8 randomly assembles papers datable between 1477 and 1482, but it was not originally meant to be arranged in this order nor perhaps to be placed here: see Noblitt 1974, 42-43.

[37] On gatherings 14-17 (WM 6 with embedded papers WM 16/17, 1476-78), see Noblitt 1974, 41.

[38] Rifkin 2003, 285-6 and 300-1. Ave Maria…virgo serena is placed near the end of gathering 15 (WM 17: 1476-78); it is followed there only by an even later addition (in a different hand), the anonymous motet O propugnator miserorum, addressing Margrave Leopold III of Austria (canonised 1485), on which see » F. SL Die Motette O propugnator miserorum. The position of the motet in Josquin’s oeuvre and the possibility of its having been written outside Milan is discussed in Fallows 2009, 60-61 and 118-19.

[39] Thus Noblitt 1974, 45.

[40] Staehelin 1977, II, 19.

[41] See » I. Kap. Three early motets (David Burn), and Strohm 1997.

[42] For Rifkin 2003, 300 and 301 n. 124, these copies belong to a later stage of the main scribal hand, but the paleographical evidence seems overstated.

[43] Strohm 1997 suggests that Isaac did have contact with ‘Germanic’ idioms as they appear in these works before 1484, but that he also disseminated these idioms to other central European musicians.

[44] See the concordance table in Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 308-11.

[45] » F. Kap. The Strahov codex (Lenka Hlávková).

[46] See the description in Gancarczyk 2011.

[47] The concordances with Strahov and Trent 90 include, predictably, some of the oldest music in Leopold, for example the English motet Anima mea liquefacta est (no. 2), doubtfully ascribed in modern research to John Forest, and the Agnus dei secundum of the Mass cycle by Jean Pullois (no. 7), both composed before 1450.

[48] » J. SL In gottes namen faren wir; » Hörbsp. ♫ Ave mundi spes/Gottes namen. On both works, see also Strohm 1993, 532-3.

[49] » F. Kap. The Speciálník codex (Lenka Hlávková).

[50] There was no Holy Roman Emperor in 1493-1508.

[51] See » D. Hofmusik. Albrecht II und Friedrich III. The composer abbreviation ‘Ar. fer.’ on no. 64 (gathering 11: 1483-84) could refer to Emperor Friedrich’s chaplain Arnold Fleron: it so happens that an ‘Arnold’, probably Fleron, is recorded at Innsbruck as ‘componist’ in both 1483 and 1484: see Strohm 1993, 518 and 531 n. 478

[52] Further on the organisation of the courtly music, see » D. Hofmusik. Innsbruck; Senn 1954.

[53] Rifkin 2003, 285 n. 103, rejects the identification of scribe ‘A’ with Krombsdorfer because of the ‘Italianate’ features of a letter he sent in 1472 to Duke Ercole d’Este (» G. Kap. Ferrara): but this calligraphy was surely chosen for the benefit of the addressee.

[54] Wolfgang Unterstetter, suffering from podagra, received from the court a weekly measure of salt: HHSt Wien (A-Whh), Kopialbuch H. Nr. 7, 1485, fol. 170v-171r.

[55] See » Abb. Synopsis, and Noblitt 1987-96, IV, 341-57; Rumbold 2018, 287-89.

[56] » I. Music and Ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck (Helen Coffey)

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Ian Rumbold and Reinhard Strohm: “The Codex of Magister Nicolaus Leopold”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/codex-magister-nicolaus-leopold-0> (2021).