“Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang” (we have added trombones and cornetts to the singing)

Since the later fifteenth century, courtly and urban alta ensembles expanded to include instruments such as crumhorns, recorders and cornetts.[19] This trend also influenced the court music of Maximilian I, as evidenced by the Triumphzug, which depicted crumhorns and shawms on the music wagons with the motto “Posaun vnd Zinckhen han wir gestelt zu dem Gesang” (we have added trombones and cornetts to the singing) (» Fig. Triumphzug wind instruments).[20] One of the most significant and lasting developments in ensemble formation around 1500 was the creation of a new ensemble type: the combination of cornetts and trombones. (» Hörbsp./ audio ♫Optime pastor.) This combination was not only new in itself but also took on a new function by joining the vocal ensemble, particularly in performing sacred vocal polyphony within the liturgy.

The early history of the cornett and the cornett-trombone ensemble cannot be fully reconstructed. However, it is evident that almost all of the earliest sources documenting the combination of singers with cornett and trombone or their use in the liturgy come from the Habsburg courts or their surroundings.[21] These include not only the depiction of the “Musica Canterey” (chapel) in the Triumphzug, Antoine Lalaing’s travel description[22], the reports of mass services during imperial diets, and municipal payment records, but also a remark about the Nuremberg trombonist Johannes Neuschl, who repeatedly worked for Maximilian I between 1502 and 1517 and was praised for “humano concentui tube sonoritatem permiscet”[23] (adding the sound of the tuba [that is, any brass instrument] to the harmony of human voices). It is therefore more than likely that the musicians at the Habsburg courts, including Schubinger, played a leading role in the development of this new practice.

As the sources clearly show, cornettists and trombonists played simultaneously with the singers, accompanying them colla parte or occasionally replacing individual vocalists, so that the respective voice was purely instrumental. (» Hörbsp./ audio ♫ Mater digna Dei.) Additionally, various reports—originating not only from the Habsburg context—suggest that wind ensembles around 1500 also took on other tasks in the liturgy. They could be used for the alternatim performance of liturgical chants, playing instrumental pieces based on the respective chant melody in alternation with the singers, or providing preludes and postludes that introduced or concluded individual chants or longer sections of the liturgical sequence.[24]

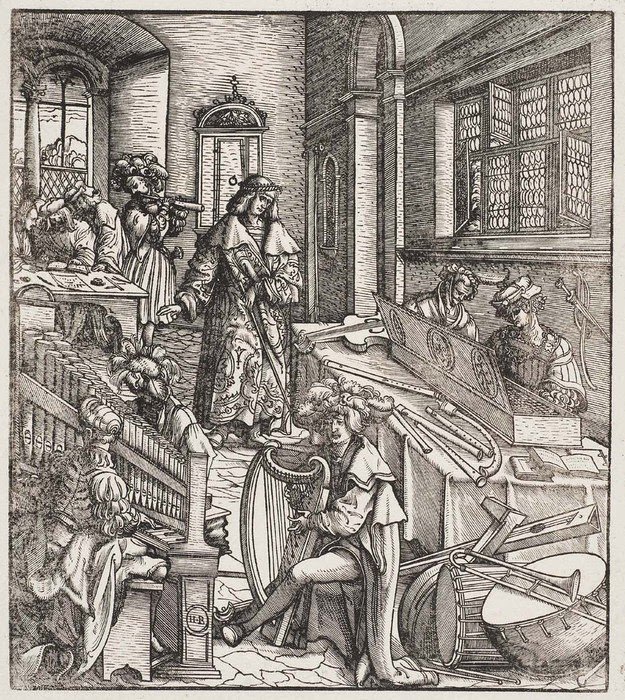

Although a group of four to five trombonists can be repeatedly documented at Maximilian’s court since around 1500,[25] it is not assumed that a “full-voiced” ensemble of cornetts and trombones was always formed. Rather, “reduced” ensembles of just one or two wind players are also to be expected, as shown by well-known depictions such as the portrayal of the ensemble with only Schubinger and Steudl in the Triumphzug or the illustration in the music chapter of the Weißkunig (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33 / Fig. Weißkunig fol. 33, in: » I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I), which shows a group of singers with a cornett player in the upper left corner.

The constellation depicted in the Triumphzug is probably not atypical. Several testimonies suggest that wind duos were more widespread in various liturgical and especially secular contexts than the standard four-member alta ensembles around 1500 might suggest. This applies to the musical life in cities, some of which only had two city pipers,[26] as well as to courtly music practice. In addition to payments to wind pairs (occasionally including Schubinger[27]), pictorial sources especially prove the existence of such duos. These include depictions of dance scenes in the tournament book Freydal, commissioned by Maximilian I. While the combination of flute (or fife) and drum dominates, the dancers are also accompanied once each by shawm (or cornett?) and trombone, by flute and trombone, and by two flutes.[28]

[19] Polk 1992a, 73–75; Polk 1987, 180; specifically for Nuremberg cf. Green 2005, 13.

[20] Depiction of the choir wagon in the Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.).

[21] See the compilation of evidence in Grassl 2019, 230–246.

[22] See, in addition to the evidence mentioned in » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 57, 58, 61, also the minutes of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris. Als derselb Augustini etlich tag im chor zur orgel vnd den sengern uff dem zingken geblausen hat, ist capitulariter conclusum, im zu erunge 2 fl. zeschencken” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091).

[23] Cochlaeus 1512, 90–91.

[24] Grassl 2017, 347–349 and 357–358; Grassl 2019, 217–221 and 227–228.

[25] Nedden 1932/1933, 28; Wessely 1956, 85, 88, 101–103, and 108–111; Polk 1992b, 86. Cf. in particular the “collective” or “group entries” in: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28r: “Item x guldin Ko mayt. Busanern dero fünffe”; Vol. 98 (1504), fol. 26r: “It. viij gulden Jörigen Holland, Jorigen Eyselin, Hannsen Stevdlin vnd Vlrich Vellen Kö. mayt. Busaunern”.

[26] Polk 1992a, 109; Green 2011, 20.

[27] See the entries in the Nördlingen account books 1506 and 1507 (» Abb. Zahlung der Stadt Nördlingen an Schubinger, 8. Juni 1506), as well as » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 67.

[28] Henning 1987, 87 (plate 183), 90 (plate 211), 94 (plate 255).

[1] From Schubinger’s service record of 1514 ( » Abb. Schubingers Dienstrevers 1514).

[2] See for example D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 89 (1495), fol. 17r; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 17r; Vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v.

[3] Grassl 1999, 208, referring to Wessely 1956, 130–134. See also the documents from 1514, according to which Schubinger was employed as a “Posaunist” (trombonist), although at that time he also, if not primarily, appeared as a cornettist.

[4] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 80 (1487), fol. 65r.

[5] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 82 (1489), fol. 66r; Vol. 84 (1490), fol. 68r; Vol. 89 (1495) [no fol.]; Vol. 90 (1496), fol. 90r. Diettel also distinguished himself from the other city pipers by occasionally receiving a slightly higher salary (40 or 44 fl. instead of the usual 36 fl.).

[6] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 81 (1488), fol. 16r.

[7] Cf. McGee 1999, 731–732; McGee 2008, 166–168.

[8] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 55 (1457), fol. 112v, online: https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-03uw/1.

[9] McGee 2000, 215–216.

[11] Grassl 2019, 223 and 231–234.

[12] Polk 1994a, 210.

[13] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r; V132–41291, (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1511/1512) fol. 209v; Protocol of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091); D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 617v: “Item ij gulden dem Augustin K mt lautenisst zu Juliane anno 1517”.

[14] See Polk 1989a, 496, 500, and 502; McGee 2000, 215; Prizer 1981, 163; further examples in Polk 1989c, 526–527, 542–543; Polk 1990, 196–197; McGee 2005, 149–150; McGee 2008, 210–212.

[15] Although polyphonic lute playing was possible to some extent with plectrum technique. See Lewon 2007. Cf. » Instrumentenmuseum Laute.

[17] » I. Ch. “Musica Lauten und Rybeben”; Nedden 1932/1933, 26–27; Ernst 1945, 222–223; Polk 1992b, 86; Polk 1994b, 407; Schwindt 2018c, 275–276.

[18] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen 1507/1508), fol. 211r. For Lenaert (or “Lionhardt”) see the references in Polk 1992b, 86–87; Polk 2001a, 93–94; Polk 2005a, 64 and 66.

[19] Polk 1992a, 73–75; Polk 1987, 180; specifically for Nuremberg cf. Green 2005, 13.

[20] Depiction of the choir wagon in the Triumphzug (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.).

[21] See the compilation of evidence in Grassl 2019, 230–246.

[22] See, in addition to the evidence mentioned in » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 57, 58, 61, also the minutes of the Constance Cathedral Chapter 1510: “ex parte Augustini lutiniste domini Cesaris. Als derselb Augustini etlich tag im chor zur orgel vnd den sengern uff dem zingken geblausen hat, ist capitulariter conclusum, im zu erunge 2 fl. zeschencken” (see Krebs 1956, 24, no. 4091).

[23] Cochlaeus 1512, 90–91.

[24] Grassl 2017, 347–349 and 357–358; Grassl 2019, 217–221 and 227–228.

[25] Nedden 1932/1933, 28; Wessely 1956, 85, 88, 101–103, and 108–111; Polk 1992b, 86. Cf. in particular the “collective” or “group entries” in: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, Vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28r: “Item x guldin Ko mayt. Busanern dero fünffe”; Vol. 98 (1504), fol. 26r: “It. viij gulden Jörigen Holland, Jorigen Eyselin, Hannsen Stevdlin vnd Vlrich Vellen Kö. mayt. Busaunern”.

[26] Polk 1992a, 109; Green 2011, 20.

[27] See the entries in the Nördlingen account books of 1506 and 1507 (» Abb. Zahlung der Stadt Nördlingen an Schubinger, 8. Juni 1506), as well as » G. Augustin Schubinger (English), note 67.

[28] Henning 1987, 87 (plate 183), 90 (plate 211), 94 (plate 255).

[29] Fundamentally Polk 1992a, 169–213; see also Gilbert 2005; Neumeier 2015, 273–290.

[30] For an overview of instrumental music-making around 1500 see Coelho/Polk 2016, insb. 189–225; Grassl 2013.

[32] Cf. from the extensive literature on this repertoire only Polk 1997; Strohm 1992; Jickeli 1996; Banks 2006.

[33] For Pirckheimer’s biography see: http://www.pirckheimer-gesellschaft.de/html/will_car.html.

[34] Edition in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 371.

[35] This could refer to the distinction between two-part and one-part bassedanze (in the terminology of contemporary French dance literature: basses danses mineurs and majeurs).

[36] Letter of June 29, 1506, edited in: Willibald Pirckheimers Briefwechsel, Vol. 1, edited by Emil Reicke (Publications of the Commission for the Study of the History of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation. Humanist Letters 4), Munich 1940, p. 380. See also Meyer 1981, 62–64 on this correspondence.

[37] Nothing more precise can be determined about “Boruni”, the arranger, i.e., probably the intabulator of Binchois’ composition. Perhaps he was an older relative of the Milanese lutenist Pietro Paolo Borrono, born around 1490 and renowned in the mid-sixteenth century.

[39] This emerges from a remark in Ulrich’s letter to Lorenzo de’ Medici (» G. Ch. Schubinger, Lorenzo de’ Medici and Isaac), stating that Ulrich had waited in vain for his brother and “Zoani Maria che suona el liuto” in Ferrara.

[40] McDonald 2019, 13–14.

[41] See especially Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 97–101; Schwindt 2018c, 542–545; see also Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 137–150; » B. Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst; » D. Zur musikalischen Quellenlage.

[42] This was either Jakob Hurlacher the Elder, who served as an Augsburg city piper from 1495 to 1530 (not just from 1508, as regularly claimed in the literature; see the entries in D-Asa Baumeisterbücher), or Jakob Hurlacher the Younger, who was a member of the Augsburg wind ensemble from 1502 to 1506 and from 1509 to 1517.

[43] See in detail Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 151–154; Neumeier 2015, 252–254.

[44] Brinzing 1998, Vol. 1, 150.

[45] Polk 1991, 158; see also Filocamo 2009. Consequently, Polk’s speculation that the “Mantüane[r] dantz” could be identical to one of the bassedanze sent by Beheim (cf. » H. Ch. A South German Humanist Correspondence) and therefore Schubinger or Giovanni Maria Ebreo its “composer” is purely speculative.

[46] Schwindt 2018c, 280.

[47] Schwindt 2018c, 280; see also Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 1, 184.

[48] Schwindt 2018c, 120–124.

[49] Unterholzner 2015, especially. 79–89, 96–98; Schwindt 2018c, 73–76.

[50] Cf. Lütteken 2010 LIT, 20–21; Polk 2001b; Schwindt 2018c, 20–24.

[51] Besides Schubinger, these include the organist Paul Hofhaimer, the lutenist Albrecht Morhanns, the trombonists Hans Neuschel and Hans Steudl, and the piper Anton Dornstetter. See the relevant image program texts in Schestag 1883, 155 and 158–160.

Recommended Citation:

Markus Grassl: „Instrumentale Musikpraxis im Lebensbereich Augustin Schubingers (ca. 1460–1531/32)“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentale-musikpraxis-im-lebensbereich-augustin-schubingers-ca-1460-153132> (2023).