Musicians for civic dancing

The musicians who might provide the accompaniment for courtly and civic dancing, whether at Maximilian’s residence at Innsbruck or in the squares and dance halls of the Empire’s cities, varied according to a number of factors, including local finances and social customs and constraints. The influence of the latter on musical performances for dancing was also reflected in the decrees of local town councils, which provide useful indications of the musicians – amateur and professional – who might be involved in these gatherings. For example, in Strasbourg in 1533 the council there declared that ‘Die rundtaenze seien zugelassen doch nicht schaendliche Lieder daran zu singen’[54] (The round dances are permitted yet not the singing of shameful songs for these). The singing of dancers as they performed in a round was common practice – the Lochamer Liederbuch’s ‘Ich spring an disem ringe’ (I leap in this round dance) exemplifies one such dance song.[55] Sung accompaniments were also provided for, it would seem, dances for royalty and nobility: as described above, in Augsburg in 1504 a ‘peasants’ dance’ involving the King was accompanied by both instrumental music and singing (» Kap. Mummerei, Moriskentanz).

Yet not only dance songs were subject to council constraints; dances accompanied by instruments were affected by similar restrictions. In Basel in 1492, for example, the council there issued a decree forbidding ‘die tantz, so uff offener gassen mit pfiffen, lutenslahen und andern seitenspilen bisshar gepflegen sind.’[56] (the dances that have until now been pursued on the open streets, with playing on pipes, lutes and with other forms of music). As Nicole Schwindt has suggested, the term ‘Saitenspiel’ appears to have been common parlance for all kinds of instrumental music, and not only that of stringed instruments.[57] The potential variety of instruments that might accompany civic and courtly dances is indicated in several Hochzeitsordnungen of the time. These documents were created by city councils to regulate the size, nature and conduct of wedding celebrations in accordance with the wedding party’s social status. Restrictions were applied not only to the number of wedding guests, their clothing and dining arrangements, but also to the type of musicians they were permitted to employ. A Hochzeitsordnung created in Frankfurt am Main in 1489, for example, explained that, dependent on the status of the bridegroom, the musicians that might be appointed for a wedding could range from visiting courtly or civic brass and wind instrumentalists (‘trumpter und pfiffer’, paid two guilders each) to resident wind instrumentalists and visiting lutenists (paid one guilder) and resident lutenists, fiddlers, drummers and bagpipers (paid half a guilder).[58]

Within the cities, use of the Stadtpfeifer for dances seems to have been primarily reserved for citizens of higher social status. During Maximilian’s reign, in the German cities these ensembles had as few as two (in the smallest towns) and as many as five (in cities such as Nuremberg and Cologne) members, who would typically play together on slide brass instruments, shawm and bombard, as well as on other wind instruments, where possible.[59] Though no musical sources can be directly linked with these ensembles due to their practice of playing from memory,[60] scholars such as Keith Polk have nevertheless determined that for dances during the late fifteenth century, musicians would have improvised upon a given tune played in slow note values (as set out in the dance treatises described above), around which the outer parts would weave one or more counterpoints for the duration of a dance. While at first, this melody was usually placed in the tenor part (having often been extracted from the tenor voice of a chanson), after 1500 the soprano line began to dominate and pieces were often constructed from repetitions of short sections rather than being through-composed (as exemplified by the music for the later basse danse and its German variant, the Hoftanz).[61] As Polk remarks, the dance pieces contained in the Augsburg Song Book, such as the aforementioned ‘Mantuanner dantz’, represent such later instrumental practices, in their repetitive phrases and soprano-dominated texture.[62]

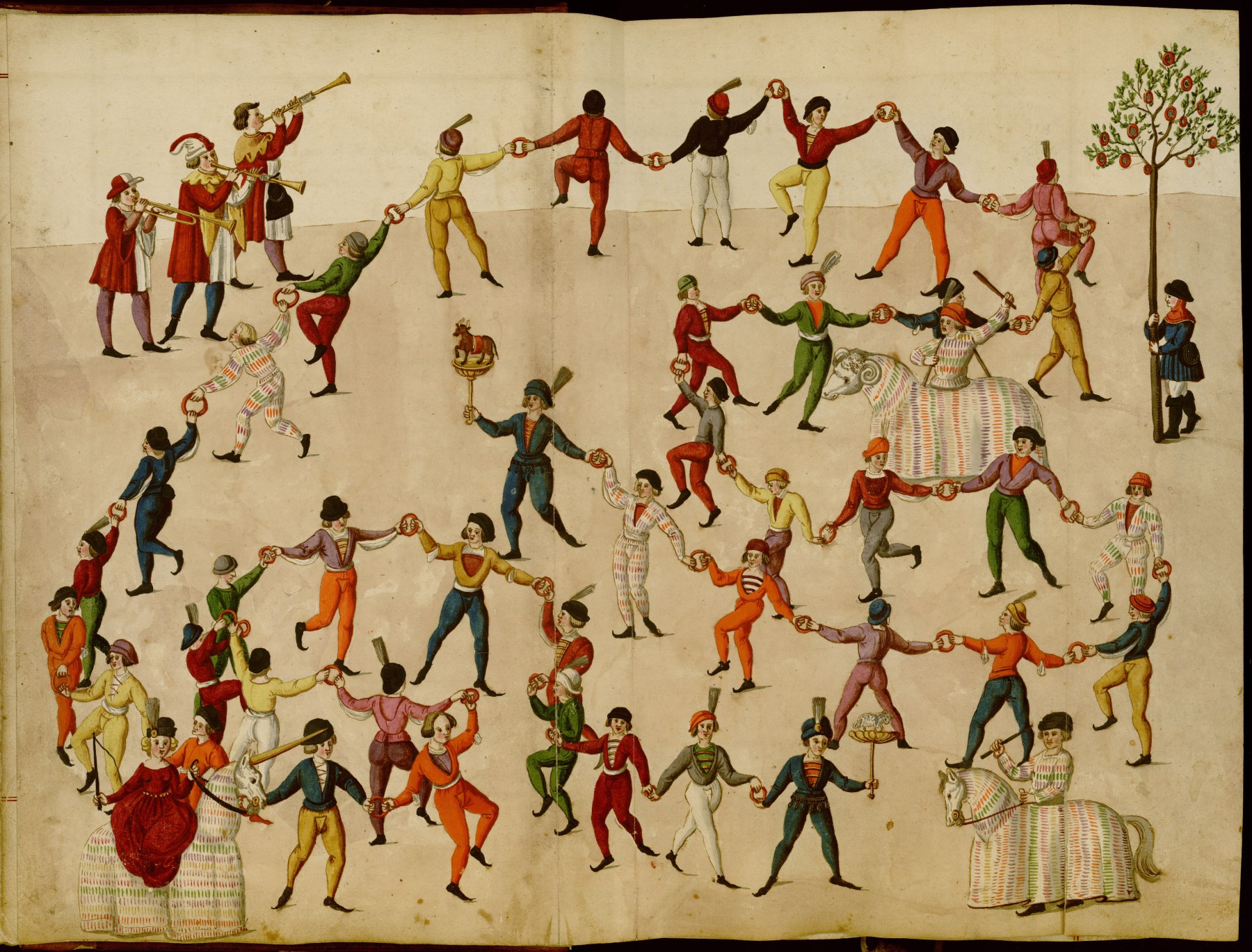

Amongst the most notable events in the civic year were the celebrations for Shrovetide, which drew on civic dancing and music in all their forms. The Nuremberg carnival held annually between 1449 and 1539 is particularly well-documented in this respect and involved processions, dances and pageants in all parts of the city. As in the mummeries at court, costumes were key to these Fastnacht celebrations, the local name for the carnival – ‘Schembartlauf’ (‘Schem’ being the Old High German for ‘mask’[63]) – reflecting the importance of costume for civic festivities too. Records of the Nuremberg council include reference to costumes of certain ‘junge Gesellen’ not only for these Fastnacht celebrations but also for other ‘Moriskentänze’ during the year,[64] and in 1491, it was Maximilian who appeared in costume for Shrovetide, in Italian and Dutch dances that were performed at the town hall.[65] The Nuremberg carnival traditionally centred around the round dance of the butchers, who were also allowed the use of the Stadtpfeifer for their dance in the open (» Abb. The dance of the Nuremberg butchers); council records confirm the continuing support for this honour over many years.[66]

[54] Vogeleis 1979, 228.

[55] Salmen 2001, 174.

[56] Ernst 1945, 203.

[57] Schwindt 2018, 83-4.

[58] Gstrein 1987, 81.

[59] Polk 1992, 109. See also » E. Musiker in der Stadt (Reinhard Strohm).

[60] On surviving written sources related to Stadtpfeifer and their music (Maastricht fragment and others), see also Strohm 1992; Brown and Polk 2001, 127.

[61] Polk 2003, 98-104; see also, Heartz 1958-1963, 313-316; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[63] Schünemann 1938, 53.

[64] See Welker 2013, 76.

[65] ‘so ließ die künigliche majestat derselben nacht ein tantz auf dem rathaus halten und mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art üben und spil treiben, darin auch der kunig persönlich in einem schempart was.’ in: Hegel 1874, 732.

[66] Several references in the records of Nuremberg’s council refer to permission granted for use of the Stadtpfeifer, Stadtknechte and Schützen for the butchers’ annual Shrovetide dance. See, for example, Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60b (Ratsbücher), Nr. 4, fol. 156r (1486), fol. 228v (1487), Nr. 5, fol. 4v (1488) and Nr. 6, fol. 2r (1493). For the development of and sources for the Schembartlauf, see Sumberg 1941 and Roller 1965.

[1] Unterholzner 2015, 51; Wiesflecker 1971, 372-9.

[2] Annotations on the diary of Reinhart Noltz, Mayor of Worms, in: Boos 1893, 379. Translations of this and the following citations by Helen Coffey, unless stated otherwise.

[3] Neudecker and Preller 1851, 231.

[4] Hegel 1874, 732.

[5] Letter from Barbara Crivelli Stampi to Anna Maria Sforza, Duchess of Ferrara, 24 January 1494. Full transcript in Aigner 2005, 76-7.

[6] Guglielmo di Ebreo claimed that anyone who had studied the exercises in his treatise (1463) would be able to master the dance of any nation. See Nevile 2008, 13.

[7] See note 5.

[8] Amongst the earliest and most significant treatises of the fifteenth century are those prepared by dance masters of the Italian courts, which include Domenico da Piacenza’s De arte saltandi e choreas ducendii (c.1440-50), Antonio Cornazano’s Libro dell’arte del danzare (first version (now lost), 1455; second version, 1465) and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Pratica Seu Arte Tripudii (1463). French and Burgundian dance practices and repertoire are conveyed in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret (now Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique MS 9085, c.1470-1501) and the related printed treatise L’Art et Instruction de Bien Dancer (published in Paris by Michel Toulouze, in or before 1496). For these, and later dance treatises, see Nevile 2004 and Heartz 1958-1963.

[9] See Heartz 1958-1963 and Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[10] See Heartz 1966; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[11] Heartz 1958-1963, 290; Nevile 2004, 21.

[12] Sparti 1986, 347; Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[13] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7. See also Sparti 1986 and Brainard 2001.

[14] Gombosi 1941, 294, 299-300; Heartz 1958-1963; Strohm 1993, 348, 553.

[15] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7.

[16] Heartz 1966, 19. A significant use of the melody occurred in the Missa La Spagna by Henricus Isaac: see Mücke-Wiesenfeldt 2012.

[17] Nevile 2004, 2.

[18] Gombosi 1941, 298; Nevile 2004, 1-3.

[19] Gachard 1876, 305-306; for a German translation of the text, see Jungmann 2002, 65-66.

[20] Fucker 1505 (not paginated), quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[21] RI XIV,4,1 n. 15882, in: Regesta Imperii Online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1502-01-09_1_0_14_4_0_49_15882

[22] Kelber 2018, 124-7.

[23] Forthcoming in Regesta Imperii Online.

[24] Franke and Welzel 2013, 34-40.

[25] Leitner 1880-1882, IV.

[26] Leitner 1880-1882, LIII.

[27] Locke 2015, 115, 117-125; Franke and Welzel 2013; Welker 2013; Vignau-Wilberg 1999, 76.

[28] ‘zu frewden seinem volk und zu eren der frembden geest … ist [er] in sonderhait geren in der mumerey gegangen’. See Schultz 1888, 82-4; also Franke and Welzel 2013, 35 and Kelber 2019, 59.

[29] ‘At in aulicorum suorum nupciis conseuit frequenter conmutatis vestibus in gencium aliquarum ritum personatus coram populo saltare. Qua humanitate atque liberalitate sibi multum fauoris tum principum tum populi precipue soeminarum conciliauit.’ See Chmel 1838, 91 for a transcript of the original text; a German translation is presented in Ilgen 1891, 57-8 and quoted in Gstrein 1987, 94.

[30] Barozzi 1880, 216.

[31] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 123-4.

[32] Letter from Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara to Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, 22 November 1507, quoted in Kooperberg 1908, 363.

[33] Heartz and Rader 2001c; Sutton et al. 2001.

[34] Translation from Guthrie and Zorzi 1986, 19.

[35] See Kelber 2019, 66-67; also Schwindt 2018, 83.

[36] Meyer 1981, 64-66, Brainard 1984, Wetzel 1990; also Brinzing 1998, 133-134.

[37] Reicke and Reimann 1940, 439-440 and 496. An English translation of Dürer’s letter is in Fry 1913, 26; Beheim’s letter is translated into French in Meyer 1981, 63.

[38] See Habich 1911, 234; also Kelber 2019, 252.

[39] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 46. Also cited in » H. Kap. Eine süddeutsche Humanistenkorrespondenz (Markus Grassl), with further explanation.

[40] See Meyer 1981, 63-64, Polk 1992, 141-2.

[41] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 47.

[42] Young 2013, 46.

[43] See Heartz 1966, 19-20 and Polk 1992, 135, 139.

[44] Heartz 1966, 20-26.

[45] Habich 1911, 220. For another pictorial document of civic dancing and musicians, see » E. Kap. Musik im Dienst, und » Abb. Patrizierfest.

[46] See Polk 1992, 141; Brinzing 1998, 139-140; Kelber 2018, 136-8. Further on the MS, see » H. Kap. Schubinger und das Augsburger Liederbuch (Markus Grassl).

[47] For an overview of the restrictions see Brunner 1987.

[48] Stiefel 1949, 135.

[49] Brunner 1987, 58-63; Salmen 2001, 165.

[50] Quoted in Polk 1992, 11.

[51] Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60a (Ratsverlässe), Nr.259, fol. 5v.

[52] Brunner 1987, 58.

[53] Salmen 1992, 23; see also Salmen 1995.

[54] Vogeleis 1979, 228.

[55] Salmen 2001, 174.

[56] Ernst 1945, 203.

[57] Schwindt 2018, 83-4.

[58] Gstrein 1987, 81.

[59] Polk 1992, 109. See also » E. Musiker in der Stadt (Reinhard Strohm).

[60] On surviving written sources related to Stadtpfeifer and their music (Maastricht fragment and others), see also Strohm 1992; Brown and Polk 2001, 127.

[61] Polk 2003, 98-104; see also, Heartz 1958-1963, 313-316; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[62] Polk 1992, 161.

[63] Schünemann 1938, 53.

[64] See Welker 2013, 76.

[65] ‘so ließ die künigliche majestat derselben nacht ein tantz auf dem rathaus halten und mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art üben und spil treiben, darin auch der kunig persönlich in einem schempart was.’ in: Hegel 1874, 732.

[66] Several references in the records of Nuremberg’s council refer to permission granted for use of the Stadtpfeifer, Stadtknechte and Schützen for the butchers’ annual Shrovetide dance. See, for example, Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60b (Ratsbücher), Nr. 4, fol. 156r (1486), fol. 228v (1487), Nr. 5, fol. 4v (1488) and Nr. 6, fol. 2r (1493). For the development of and sources for the Schembartlauf, see Sumberg 1941 and Roller 1965.

[67] ‘Der ro. kinig und sein sun Philipps sind zü pfingsten 1496 hie gewessen. da hat man 10 füder holtz auff den Fronhoff gefiert, und nach ave Maria zeit ain himelsfeur gehebt, und hertzog Philipp und sein adel haben 3 mall um das feur dantzt, und sind da all trumether gewessen, und hand da ob 10000 menschen dantzt.’ in: Roth 1894, 71-72.

[68] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[69] Donauwörth Stadtarchiv, Johann Knebel, Stadtchronik (unpublished), fo.206v (cited in correspondence from Donauwörth Stadtarchiv).

[70] Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 86.

[71] Gstrein 1987, 88.

[72] ‘sunst ist noch ein Klein peucklin, das haben die frantzosen und niderlender ser zu den Schwegeln gebraucht, und sunderlich zu dantz, oder zu den hochzyten.’ (there is also a small kettledrum, which the French and Netherlanders have often used, above all for dancing or for weddings). Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 91.

[73] Gstrein 1987, 89; Schwindt 2018, 81-2.

[74] Hoffmann-Axthelm 1983, 96. See also Green 2011, 17.

[75] Sumberg 1941, 88.

[76] Translation from Sutton 1967, 39, 47. See also Brunner 1983, 54-5.