Basse Danse, Bassa Danza, Ballo

The engagement of Maximilian, Bianca Maria and their court with this core international repertoire of dances is already evidenced several years before their travels to Worms and Mechelen in 1494. In 1491, for example, Maximilian had participated in ‘mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art’[4] (several dances in the Italian and Netherlandish style) while in Nuremberg, and in December 1493, shortly after her initial arrival in Innsbruck from Milan, Bianca Maria was reported as having danced ‘most beautifully in the French, Italian and German styles’.[5] While these accounts indicate the familiarity with which both King and Queen engaged with particular national dance styles, elsewhere we find evidence of local dance customs that challenged the participants with unfamiliar steps. For example, envoys of the Ferrarese court remarked on the Italian dances performed by Bianca Maria following her arrival in Innsbruck in December 1493, which included ‘the longaresca, as is sometimes danced in the castle in Milan’ (» I. Kap. The arrival of Bianca Maria Sforza). The Innsbruck courtiers then appear to have performed a dance unfamiliar to those recently arrived from the Sforza court, the Ferrarese ambassadors noting a performance of the ‘Pizighitone, which the Milanese cannot get used to’ (» I. Kap. Entertainments under Sigmund and Katharina). Despite these differences, a common repertoire of choreographic elements seems to have existed that allowed courtiers from various regions of Europe to engage with even unfamiliar dances.[6] For example, Barbara Crivelli Stampi, who had accompanied Bianca Maria from Italy to Innsbruck, apparently familiarised herself with the German dances she encountered there by relating these to the customary dances of Milan.[7]

The primary forms of dance performed at European courts at that time can be determined from several treatises of French, Burgundian and Italian origin, the earliest of which was written in the mid-15th century: no equivalent sources have been identified for the German-speaking lands for this period.[8] At the heart of the dance repertoire described in these treatises stood the basse danse associated with the Burgundian court, its Italian equivalent the bassa danza, and another Italian courtly dance form, the ballo. As reflected in its name, the Burgundian basse danse (literally ‘low dance’) was a steady, serene dance performed by one or more couples, often in procession, with steps low to the ground and lacking leaps or rapid movements. The basse danse had four basic dance steps (five if including the reverence – the bow by the male dancer at the start of each dance) which were strictly organised into a number of distinct patterns known as mesures. A single dance comprised several mesures, which were also carefully arranged so that different step patterns alternated with one other. During the fifteenth century, basse danses varied in their duration as a result of the various combinations of mesures that might be employed. However, as Daniel Heartz has established, treatises of the early sixteenth century point to the gradual emergence and eventual predominance of a standardised basse danse choreography.[9] Heartz also identifies a German off-shoot of the basse danse that appears to represent this later stage of the dance in its repetition of step patterns; this also introduced a distinctive syncopated rhythm in its musical accompaniment, not found in the Burgundian dance form (see » Kap. Urban Courtly Dance). Both the original and German adaptation of the basse danse were typically followed by an after-dance (called the ‘pas de brebant’ in the Netherlands) that was twice as fast as the original dance and allowed for quicker movements and small leaps.[10]

The Italian bassa danza similarly promoted grace and elegance in the dancers’ movements but allowed for greater choreographic freedom in its application of nine different dance steps. The Italian dancers were not restricted to performing in pairs (as in the basse danse) but in various combinations and they also executed dance figures that entailed, for example, brief moments of separation and reunion, or the exchange of dancers’ places.[11] Furthermore, while the bassa danza, like the basse danse, employed a single, steady metre throughout, it might include sections that drew on the faster metres and movements (including jumps and leaps) of the three other primary dance forms associated with the Italian courts: the ‘quarternaria’ (a sixth faster than the bassa danza, and also referred to as the ‘saltarello tedesco’ due to its alleged popularity with the Germans), the ‘saltarello’ (the customary after-dance of the bassa danza at two-sixths faster) and the ‘piva’ (the fastest of the four dance types at twice the speed of the bassa danza; by that time, the ‘piva’ (like the ‘quarternaria’) was not favoured as an independent dance in the Italian courts).[12] The variety of metres and steps that might be found in a bassa danza was employed to a greater extent in the other primary Italian court dance, the ballo, which incorporated additional, more decorative movements. Created by specially appointed dance masters (some of whom authored the treatises mentioned above), balli comprised a number of short, distinct sections, each of which presented the metre and steps of one of the aforementioned four Italian dance forms. The frequent contrasts in dance metres and steps and the various ways in which the dancers interacted in balli were key to the dances’ unique choreographies, which ranged from ornamental dances to pieces that conveyed particular dramatic narratives.[13]

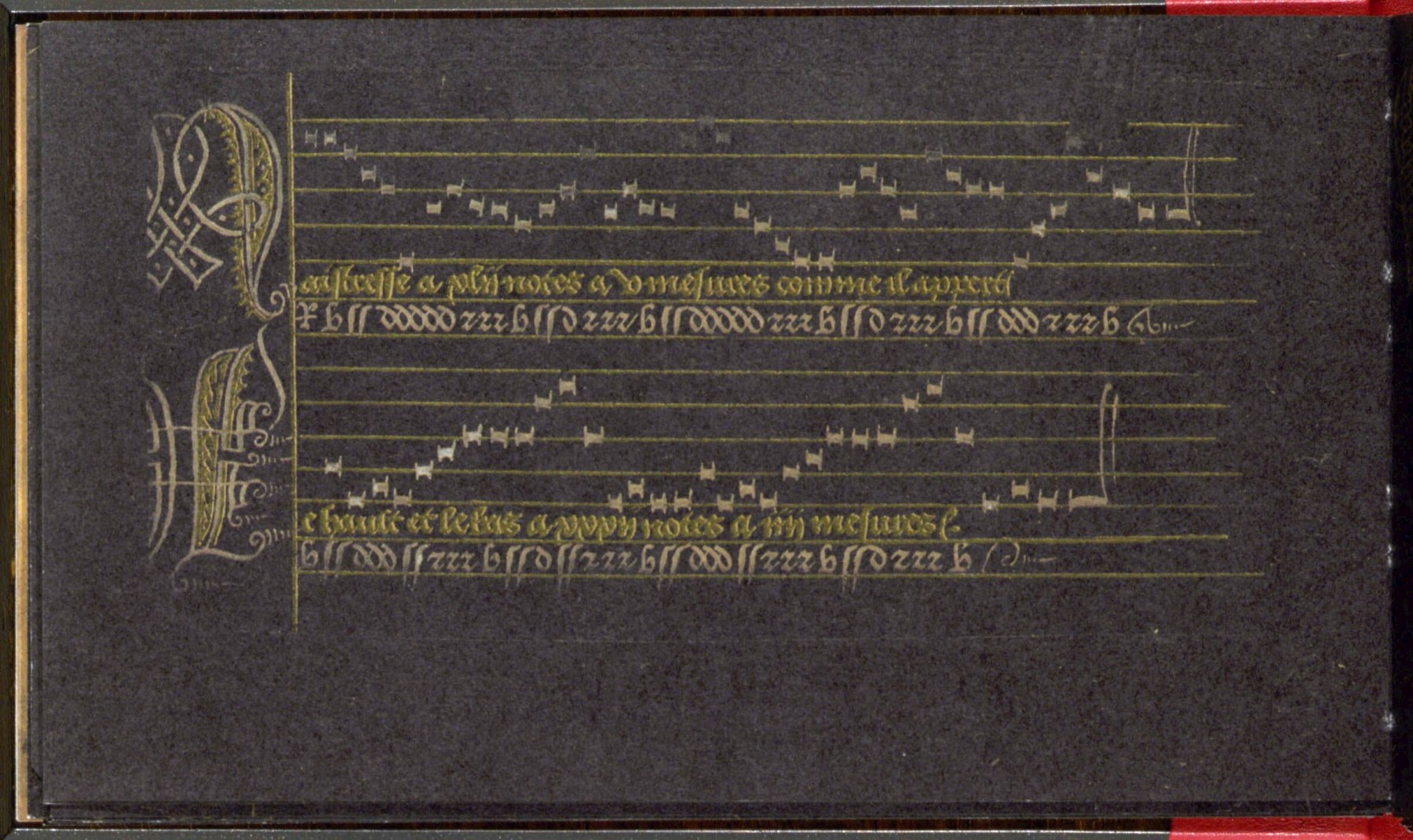

Several of the treatises that describe French/Burgundian and Italian dance practices also present melodies that might be performed alongside particular dances. These melodies were not included for the instrumentalists who would accompany the dances but instead served as aide-mémoires for the dancers, each musical note being equivalent to one dance step. For example, in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, the slow pace of the dances was conveyed by the presentation of the dance tunes in breves, which are annotated with initials that represented the particular dance steps that would be enacted during the duration of each note (» Abb. Maistresse and Le hault et le bas). It is assumed that the instrumentalists who accompanied the dances did so through improvisation around these melodies, which were adapted to fit the length of each dance and were often extracted from the soprano or tenor line of a well-known polyphonic chanson (» Kap. Musicians for civic dancing); some balli were, however, also sung by participants.[14] Whereas the cantus firmi of the basse danses or basse danze were presented in slow notes of equal value (to be adapted by musicians as appropriate), balli melodies usually indicated the frequent changes in rhythm in a dance and reflect the close relationship between the melody and dance steps, both of which were carefully devised by a dance master. As a result, in the aforementioned early dance treatises, descriptions of balli are often accompanied by their particular melodies whereas only three bassa danza tunes are included, perhaps indicating that a melody might be more easily adapted to this less complex dance form.[15] Many of the melodies presented in the dance treatises achieved widespread popularity across Europe, including in settings for keyboard and string instruments for private use: one such tune, ‘La Spagna’ – the only melody to appear in both bassa danza and basse danse sources - was distributed in over 300 different versions.[16]

[4] Hegel 1874, 732.

[5] Letter from Barbara Crivelli Stampi to Anna Maria Sforza, Duchess of Ferrara, 24 January 1494. Full transcript in Aigner 2005, 76-7.

[6] Guglielmo di Ebreo claimed that anyone who had studied the exercises in his treatise (1463) would be able to master the dance of any nation. See Nevile 2008, 13.

[7] See note 5.

[8] Amongst the earliest and most significant treatises of the fifteenth century are those prepared by dance masters of the Italian courts, which include Domenico da Piacenza’s De arte saltandi e choreas ducendii (c.1440-50), Antonio Cornazano’s Libro dell’arte del danzare (first version (now lost), 1455; second version, 1465) and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Pratica Seu Arte Tripudii (1463). French and Burgundian dance practices and repertoire are conveyed in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret (now Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique MS 9085, c.1470-1501) and the related printed treatise L’Art et Instruction de Bien Dancer (published in Paris by Michel Toulouze, in or before 1496). For these, and later dance treatises, see Nevile 2004 and Heartz 1958-1963.

[9] See Heartz 1958-1963 and Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[10] See Heartz 1966; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[11] Heartz 1958-1963, 290; Nevile 2004, 21.

[12] Sparti 1986, 347; Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[13] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7. See also Sparti 1986 and Brainard 2001.

[14] Gombosi 1941, 294, 299-300; Heartz 1958-1963; Strohm 1993, 348, 553.

[15] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7.

[16] Heartz 1966, 19. A significant use of the melody occurred in the Missa La Spagna by Henricus Isaac: see Mücke-Wiesenfeldt 2012.

[1] Unterholzner 2015, 51; Wiesflecker 1971, 372-9.

[2] Annotations on the diary of Reinhart Noltz, Mayor of Worms, in: Boos 1893, 379. Translations of this and the following citations by Helen Coffey, unless stated otherwise.

[3] Neudecker and Preller 1851, 231.

[4] Hegel 1874, 732.

[5] Letter from Barbara Crivelli Stampi to Anna Maria Sforza, Duchess of Ferrara, 24 January 1494. Full transcript in Aigner 2005, 76-7.

[6] Guglielmo di Ebreo claimed that anyone who had studied the exercises in his treatise (1463) would be able to master the dance of any nation. See Nevile 2008, 13.

[7] See note 5.

[8] Amongst the earliest and most significant treatises of the fifteenth century are those prepared by dance masters of the Italian courts, which include Domenico da Piacenza’s De arte saltandi e choreas ducendii (c.1440-50), Antonio Cornazano’s Libro dell’arte del danzare (first version (now lost), 1455; second version, 1465) and Guglielmo Ebreo da Pesaro’s De Pratica Seu Arte Tripudii (1463). French and Burgundian dance practices and repertoire are conveyed in the basse danse manuscript associated with the Burgundian court of Maximilian’s daughter Margaret (now Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique MS 9085, c.1470-1501) and the related printed treatise L’Art et Instruction de Bien Dancer (published in Paris by Michel Toulouze, in or before 1496). For these, and later dance treatises, see Nevile 2004 and Heartz 1958-1963.

[9] See Heartz 1958-1963 and Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[10] See Heartz 1966; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[11] Heartz 1958-1963, 290; Nevile 2004, 21.

[12] Sparti 1986, 347; Heartz and Rader 2001a.

[13] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7. See also Sparti 1986 and Brainard 2001.

[14] Gombosi 1941, 294, 299-300; Heartz 1958-1963; Strohm 1993, 348, 553.

[15] Aigner 2005, 45-54; Nevile 2004, 26-7.

[16] Heartz 1966, 19. A significant use of the melody occurred in the Missa La Spagna by Henricus Isaac: see Mücke-Wiesenfeldt 2012.

[17] Nevile 2004, 2.

[18] Gombosi 1941, 298; Nevile 2004, 1-3.

[19] Gachard 1876, 305-306; for a German translation of the text, see Jungmann 2002, 65-66.

[20] Fucker 1505 (not paginated), quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[21] RI XIV,4,1 n. 15882, in: Regesta Imperii Online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1502-01-09_1_0_14_4_0_49_15882

[22] Kelber 2018, 124-7.

[23] Forthcoming in Regesta Imperii Online.

[24] Franke and Welzel 2013, 34-40.

[25] Leitner 1880-1882, IV.

[26] Leitner 1880-1882, LIII.

[27] Locke 2015, 115, 117-125; Franke and Welzel 2013; Welker 2013; Vignau-Wilberg 1999, 76.

[28] ‘zu frewden seinem volk und zu eren der frembden geest … ist [er] in sonderhait geren in der mumerey gegangen’. See Schultz 1888, 82-4; also Franke and Welzel 2013, 35 and Kelber 2019, 59.

[29] ‘At in aulicorum suorum nupciis conseuit frequenter conmutatis vestibus in gencium aliquarum ritum personatus coram populo saltare. Qua humanitate atque liberalitate sibi multum fauoris tum principum tum populi precipue soeminarum conciliauit.’ See Chmel 1838, 91 for a transcript of the original text; a German translation is presented in Ilgen 1891, 57-8 and quoted in Gstrein 1987, 94.

[30] Barozzi 1880, 216.

[31] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 123-4.

[32] Letter from Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara to Maximilian’s daughter Margaret, 22 November 1507, quoted in Kooperberg 1908, 363.

[33] Heartz and Rader 2001c; Sutton et al. 2001.

[34] Translation from Guthrie and Zorzi 1986, 19.

[35] See Kelber 2019, 66-67; also Schwindt 2018, 83.

[36] Meyer 1981, 64-66, Brainard 1984, Wetzel 1990; also Brinzing 1998, 133-134.

[37] Reicke and Reimann 1940, 439-440 and 496. An English translation of Dürer’s letter is in Fry 1913, 26; Beheim’s letter is translated into French in Meyer 1981, 63.

[38] See Habich 1911, 234; also Kelber 2019, 252.

[39] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 46. Also cited in » H. Kap. Eine süddeutsche Humanistenkorrespondenz (Markus Grassl), with further explanation.

[40] See Meyer 1981, 63-64, Polk 1992, 141-2.

[41] Translation adapted from Young 2013, 47.

[42] Young 2013, 46.

[43] See Heartz 1966, 19-20 and Polk 1992, 135, 139.

[44] Heartz 1966, 20-26.

[45] Habich 1911, 220. For another pictorial document of civic dancing and musicians, see » E. Kap. Musik im Dienst, und » Abb. Patrizierfest.

[46] See Polk 1992, 141; Brinzing 1998, 139-140; Kelber 2018, 136-8. Further on the MS, see » H. Kap. Schubinger und das Augsburger Liederbuch (Markus Grassl).

[47] For an overview of the restrictions see Brunner 1987.

[48] Stiefel 1949, 135.

[49] Brunner 1987, 58-63; Salmen 2001, 165.

[50] Quoted in Polk 1992, 11.

[51] Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60a (Ratsverlässe), Nr.259, fol. 5v.

[52] Brunner 1987, 58.

[53] Salmen 1992, 23; see also Salmen 1995.

[54] Vogeleis 1979, 228.

[55] Salmen 2001, 174.

[56] Ernst 1945, 203.

[57] Schwindt 2018, 83-4.

[58] Gstrein 1987, 81.

[59] Polk 1992, 109. See also » E. Musiker in der Stadt (Reinhard Strohm).

[60] On surviving written sources related to Stadtpfeifer and their music (Maastricht fragment and others), see also Strohm 1992; Brown and Polk 2001, 127.

[61] Polk 2003, 98-104; see also, Heartz 1958-1963, 313-316; Heartz and Rader 2001b.

[62] Polk 1992, 161.

[63] Schünemann 1938, 53.

[64] See Welker 2013, 76.

[65] ‘so ließ die künigliche majestat derselben nacht ein tantz auf dem rathaus halten und mancherlei tentz auf welsche und niderlendische art üben und spil treiben, darin auch der kunig persönlich in einem schempart was.’ in: Hegel 1874, 732.

[66] Several references in the records of Nuremberg’s council refer to permission granted for use of the Stadtpfeifer, Stadtknechte and Schützen for the butchers’ annual Shrovetide dance. See, for example, Nuremberg Staatsarchiv, Rep.60b (Ratsbücher), Nr. 4, fol. 156r (1486), fol. 228v (1487), Nr. 5, fol. 4v (1488) and Nr. 6, fol. 2r (1493). For the development of and sources for the Schembartlauf, see Sumberg 1941 and Roller 1965.

[67] ‘Der ro. kinig und sein sun Philipps sind zü pfingsten 1496 hie gewessen. da hat man 10 füder holtz auff den Fronhoff gefiert, und nach ave Maria zeit ain himelsfeur gehebt, und hertzog Philipp und sein adel haben 3 mall um das feur dantzt, und sind da all trumether gewessen, und hand da ob 10000 menschen dantzt.’ in: Roth 1894, 71-72.

[68] Quoted in Kelber 2018, 128.

[69] Donauwörth Stadtarchiv, Johann Knebel, Stadtchronik (unpublished), fo.206v (cited in correspondence from Donauwörth Stadtarchiv).

[70] Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 86.

[71] Gstrein 1987, 88.

[72] ‘sunst ist noch ein Klein peucklin, das haben die frantzosen und niderlender ser zu den Schwegeln gebraucht, und sunderlich zu dantz, oder zu den hochzyten.’ (there is also a small kettledrum, which the French and Netherlanders have often used, above all for dancing or for weddings). Quoted in Gstrein 1987, 91.

[73] Gstrein 1987, 89; Schwindt 2018, 81-2.

[74] Hoffmann-Axthelm 1983, 96. See also Green 2011, 17.

[75] Sumberg 1941, 88.

[76] Translation from Sutton 1967, 39, 47. See also Brunner 1983, 54-5.