Sources of Polyphony in the Bohemian lands c. 1470–c. 1500

The special history of Bohemia and its polyphonic music

The musical tradition of the fifteenth-century Bohemian Lands had its own individual character, influenced by the specific political and religious situation in the country. After the death of Johannes Hus, a popular Czech preacher, university teacher and critic of the contemporary church, at the stake in Constance in 1415, the explosive atmosphere in Bohemia resulted in the Hussite wars (1419–1436). This development had considerable effects on sacred music. On the one hand, the institutional foundation of the Catholic church was broken; many clerics left the country and settled down in the neighbouring regions (i. e. Lusatia, Silesia, Hungary, Bavaria). In the second half of the century, the Catholic church was only partly reestablished as an institution. On the other hand, the ideology of the Hussite reformation supported the development of sacred songs (mostly monophonic in Czech), some of them surviving within the repertories of protestant churches even centuries later (» B. Geistliches Lied, Kap. Patris sapientia). Also, the creation of the liturgy in Czech based on the traditional Roman plainchant in the 1420s can be seen as a prelude to the activities of Martin Luther in the sixteenth century.

The cultivation of polyphony in the late medieval Bohemian Lands was closely connected to the existence of the University of Prague (founded 1348), where the knowledge of mensural theory is documented around 1370 at the latest by a treatise written there by an anonymous author.[1] This local creativity inspired by foreign impulses gave birth to a specific Central European variant of Ars nova music, represented by polytextual motets of the „Engelberg“ type. Among them, there is at least one preserved example of a local isorhythmic motet, Ave coronata/Ave spes.[2] There are several kinds of polyphonic song (cantio), which include a circle-canon called rotulum, pieces that imitate the performance on instruments (trumpetum, stampetum), and canon-like compositons inspired by the genre of the French or Italian chace/caccia (katchetum).[3] Because of a lack of fourteenth-century sources, we learn about this repertory only through late fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sources which document the musical tradition cultivated by the Utraquist Church (followers of the Hussites after 1436), which lasted until the recatholicization which started around 1620. The presence of „archaic“ pieces in those late manuscripts was one of the reasons why the musical culture of Bohemia was until recently thought to have resulted from cultural isolation caused by the Hussite wars, and by the political and religious instability following thereafter.[4]

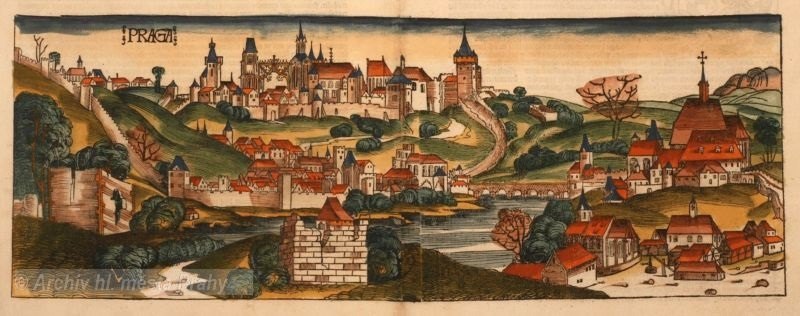

The main Catholic institution was the St Vitus Cathedral in Prague, which had a large ensemble of singers before 1419; but its influence radically decreased after the war.[5] The institution‘s insufficient material background did not allow any other activities than those necessary to celebrate the liturgy.

The Strahov Codex: dating and contents

It is in the second half of the fifteenth century that important collections of Franco-Flemish polyphony originated in Bohemia (Strahov Codex: » CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47, Speciálník Codex: » CZ-HKm Ms. II A 7). These are testimonies of a lively interest of both Catholic (Strahov Codex) as well as Utraquist intellectuals (Speciálník Codex) in the polyphonic music of their time, as they include pieces written by local composers together with compositions imported from different regions of Latin Europe. Because of a lack of sources it is hard to say when and how far Franco-Flemish polyphony penetrated the Catholic milieu in Bohemia. The Prague archdiocese had no archbishop for several decades, and there were many young men on the road abroad (mostly to Italy) to receive the ordination, as well as many students to receive their degrees or just to study outside Prague.[6] We can therefore assume at least some individual knowledge of contemporary polyphony before the 1460s, when the collection known as the Strahov Codex (c. 1467–1470) was compiled.[7] The manuscript of a modest „travel“ size (215 x 150 mm), but at the same time an impressive volume (614 pages) is a Catholic source of almost 300 polyphonic compositions.[8] These are systematically organised according to their liturgical function as follows: introits, Mass ordinary settings, motets, songs, hymns and Magnificats. The repertory is partly known from other contemporary Central European music collections (e. g. the later Trent Codices, the Schedel Songbook, the Nicolaus Leopold Codex),[9] but more than half of the copied pieces are transmitted in this manuscript only. The Strahov Codex is an important source of music by leading fifteenth-century composers as Guillaume Du Fay, Johannes Puillois, Johannes Cornago or Walter Frye. At the same time we find there compositions by less known or unknown authors, such as Standley, Philippus Francis or Flemmik. In terms of quantity, the leading figure within the repertory of the Strahov Codex is undoubtely the composer Johannes Tourout. Although his music was already known to musicologists more than 100 years ago, his identity and his connections to Central Europe were discovered only recently.[10]

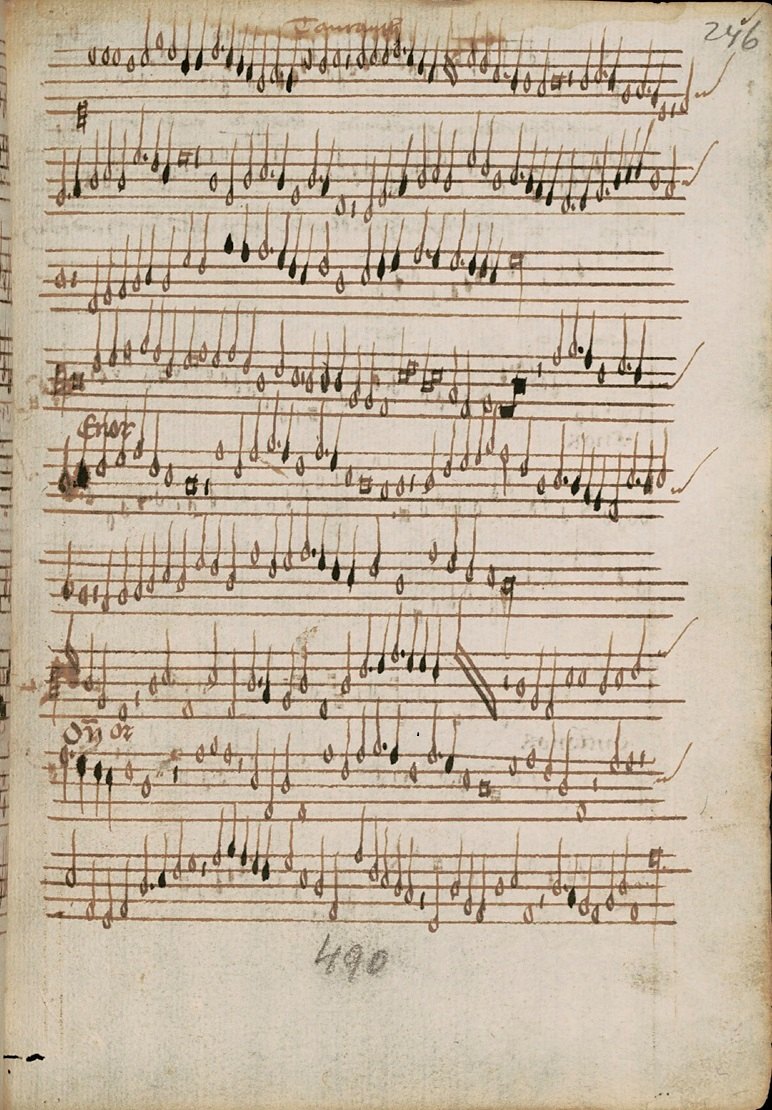

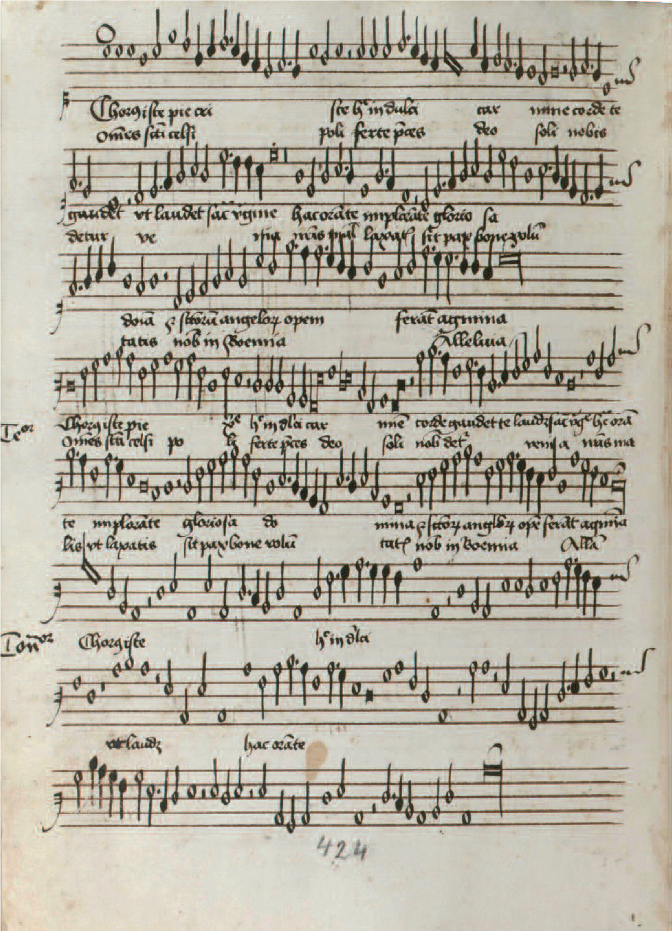

Johannes Tourout was a cleric from the diocese of Tournai (from the town of Torhout?) and he was born most probably around 1430. Given the scarcity of sources documenting his life, we can only assume that he received a high-quality music training in an important church centre of that region (Antwerp?). By 1460 he was cantor et familiaris of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III (1415−1493) , but there is no information concerning the beginning of his service at the imperial court.[11] Even so, it is evident that he reached Central Europe as an experienced composer, familiar with all forms of Franko-Flemish polyphony of that time. The oldest sources containing compositions by Tourout originated around 1460; these are the Trent Codices » I-TRbc 88 and » I-TRbc 89, the Schedel Songbook and the Buxheim Organ Book.[12] The dating of these manuscripts helps us, in connection with the testimony given by the single biographical document, to establish an approximate terminus post quem for the composer’s activity in Central Europe. Apart from compositions attributed directly to Johannes Tourout in fifteenth-century musical sources,[13] there are several anonymous masses, motets and songs composed probably by this author as well.[14] The Strahov Codex is one of the most important manuscripts in this respect, containing around 30 polyphonic songs, mostly unique chansons, which were originally settings of French poetry composed by Tourout or by musicians from his circle, but are preserved here without text or with a new Latin one. The recently discovered document on the relationship of this Flemish composer to Central Europe is of key importance for the discussion of the origin and function of the Strahov Codex. An oft-cited work by Tourout has been copied without words in the Strahov Codex (» Abb. Chorus iste, Strahov), but somewhat later with the Latin text Chorus iste in the Speciálník Codex (» Abb. Chorus iste, Specialník). This composition may well have originated as a French-texted chanson, to judge by its form.[15]

The contrafactum Chorus iste is a prayer text, which at the end invokes peace for the members of a church choir in Bohemia (“sit pax bone voluntatis nobis in Bohemia”):[16]

Chorus iste, pie Christe,

Hoc in dulci carmine

Corde te gaudet ut laudet

Sacerdotem virgine.

Omnes sancti celsi poli

Ferte preces deo soli

Nobis detur venia.Hac orante implorante

Gloriosa domina

Et sanctorum angelorum

Opem ferant agmina,

Nostris malis ut laxatis

Sit pax bone voluntatis

Nobis in Bohemia.

Alleluia.(This chorus, merciful Christ, is joyous at heart to praise with this sweet song you, the priest, through the virgin. All you Saints of the high heavens, bring your prayers before God alone, that mercy be given to us. May she, the glorious mistress, pray and plead, and the heavenly hosts assist, so that our wrongdoings are remitted and peace of good will is given to us in Bohemia. Alleluia.)

The concept and content of the Strahov Codex can be easily compared with the younger Trent Codices (I-TRbc 88 –91) or the oldest fascicles of the Nicolaus Leopold Codex. These collections of polyphony connected with activities of teachers of the cathedral school in Trent or with the Habsburg court in Innsbruck arguably transmit part of the repertory of the imperial chapel.[17]

The Prague connection of the Strahov Codex

Notwithstanding the Central European character of the Strahov Codex (» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47), it was compiled with regard to the liturgy of the Prague diocese by scribes familiar with the Czech variant of the staff notation (nota rhombica),[18] but the question on the origin of the manuscript still remains a burning one. The catholic character of the collection, which contains at the same time polyphonic settings of local hymns for St Wenceslas and St Procopius, in particular, with specific Bohemian melodic variants,[19] and songs with German texts, brought different catholic localities of the Bohemian Lands with German-speaking population into the discussion: East Bohemia or Silesia,[20] Olomouc (Olmütz)[21] or České Budějovice (Budweis). Recent research, however, suggests a connection of the source with Prague Cathedral. Notwithstanding the problematic position of the Catholic church, which was in a minority in Bohemia (but not in other parts of the lands of the Bohemian Crown), there were highly educated men of international horizons and contacts leading the institution, who held university degrees obtained abroad (e. g. in Padua or Bologna). If we look closer at the collection of 60 polyphonic hymns, the largest one in fifteenth-century sources, we find several interesting representatives of different traditions (e. g. South Germany, Trent or Italy) in addition to settings of local melodies known from Bohemian manuscripts. Taken together, this set of polyphonic compositions suggests „a travel journal“ of a scribe of the codex (at least the principal one), who might have collected music for use at Prague cathedral or its school „on the road“ to Italy and back. At the same time there are several high-quality compositions on local cantus firmi (including, for example, a setting of the hymn Sanctorum meritis inclita, fol. 282v–283r, with a local melodic variant), which attest to a high level of musical education of the Bohemian catholic intellectual circles in the 1460s. Just to give an example, the Utraquist Hilarius of Leitmeritz (Litoměřice) received his degree at Prague University in 1451 and continued his studies in Bologna from 1451 to 1454. He returned from Italy as a strong critic of the Utraquist church and the leader of the catholic opposition against the Utraquist bishop Johannes Rokycana and the Bohemian King Georg of Podiebrad (Poděbrady). From 1461 to his death in 1469 he was the administrator of the Prague diocese and the first man of the Catholic church. During this period he was travelling to several cities abroad (including Nuremberg, Rome and Graz).[22] If not Hilarius in person, who had opportunities to meet and hear contemporary polyphony during his journeys, the copying of music for the Strahov Codex might have been a work of other members of the Prague cathedral staff.

Utraquist church music

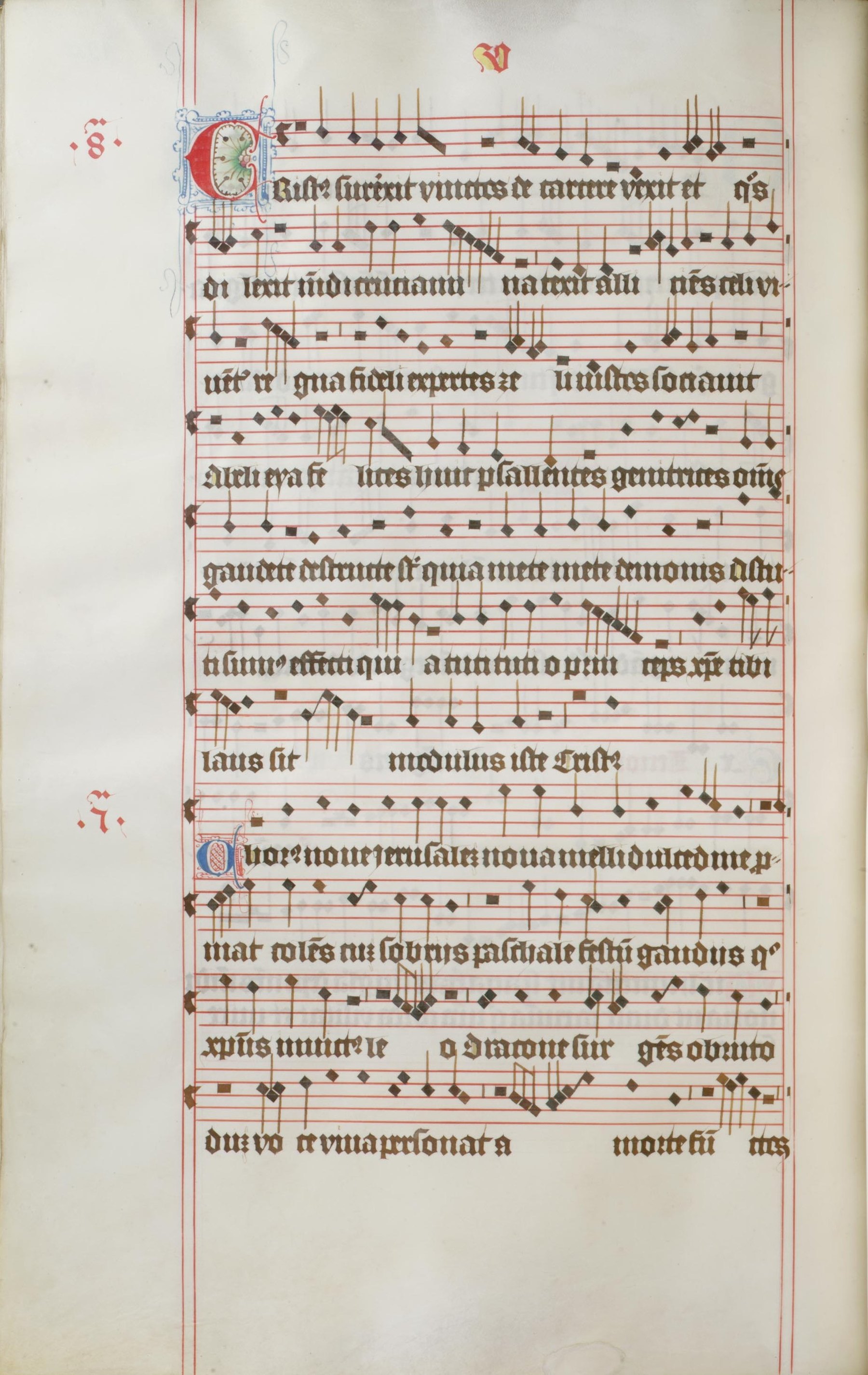

A new chapter of fifteenth-century music history starts with the Utraquist church, which added a novelty to the liturgy – a communion under both kinds for the whole congregation. Concerning the repertory of liturgical music, the Utraquists remained largely faithful to the tradition from the time before the Hussite Wars (i. e. before 1420). As we can conclude from the extant musical sources, a redaction of the liturgical repertory took place during the 1470s or 1480s, which resulted in a specific kind of choirbook called „a Utraquist gradual“.[23] Apart from standard late medieval graduals with plainchant for the Mass liturgy, there are extensive collections of monophonic songs and polyphonic compositions as well, selected and organized according to a common model.[24] A specific feature of Utraquist music culture is a conscious return to the „archaic“ polyphony of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries (including compositions by Petrus Wilhelmi de Grudencz), which is to be found very rarely in the neighbouring regions (e. g. Silesia or Bavaria) after 1450. Polyphonic compositions written in older styles belonged to a core repertory of the school choirs, where they fulfilled mainly a didactic function, partly a liturgical one. At the end of the fifteenth century, when choirs of educated laymen, called litterati, were established, these archaic pieces might also have been sung at their social meetings as generally known pieces from school times. The polytextual motet Christus surrexit vinctos/ Chorus nove Ierusalem/ Christus surrexit (» Hörbsp. ♫ Christus surrexit vinctos) reflects this long tradition; the piece was copied both in the Speciálník Codex and a slightly later Utraquist gradual with polyphonic works, the richly illuminated Franus Codex (» CZ-HKm Ms. II A 6; 1505) from Hradec Kralové (» Abb. Christus surrexit, Franus).

On the other hand, there is no doubt about the active interest of Utraquist intellectuals in the Franko-Flemish polyphony of this time. This kind of music was not only imported (e. g. from France, Italy, Bavaria or Austria) and copied, but it also inspired local composers to write new pieces in this style, even with Czech words.[25] In the Utraquist sources we do not find any polyphonic settings of the Mass Ordinary text of the Agnus Dei, but there are some of them copied without text only or underlaid with a new text (contrafacta), ready to fulfil a different liturgical function.[26] This phenomenon is probably related to the practical implementation of the communion under both kinds to the Mass liturgy.

The Speciálník Codex

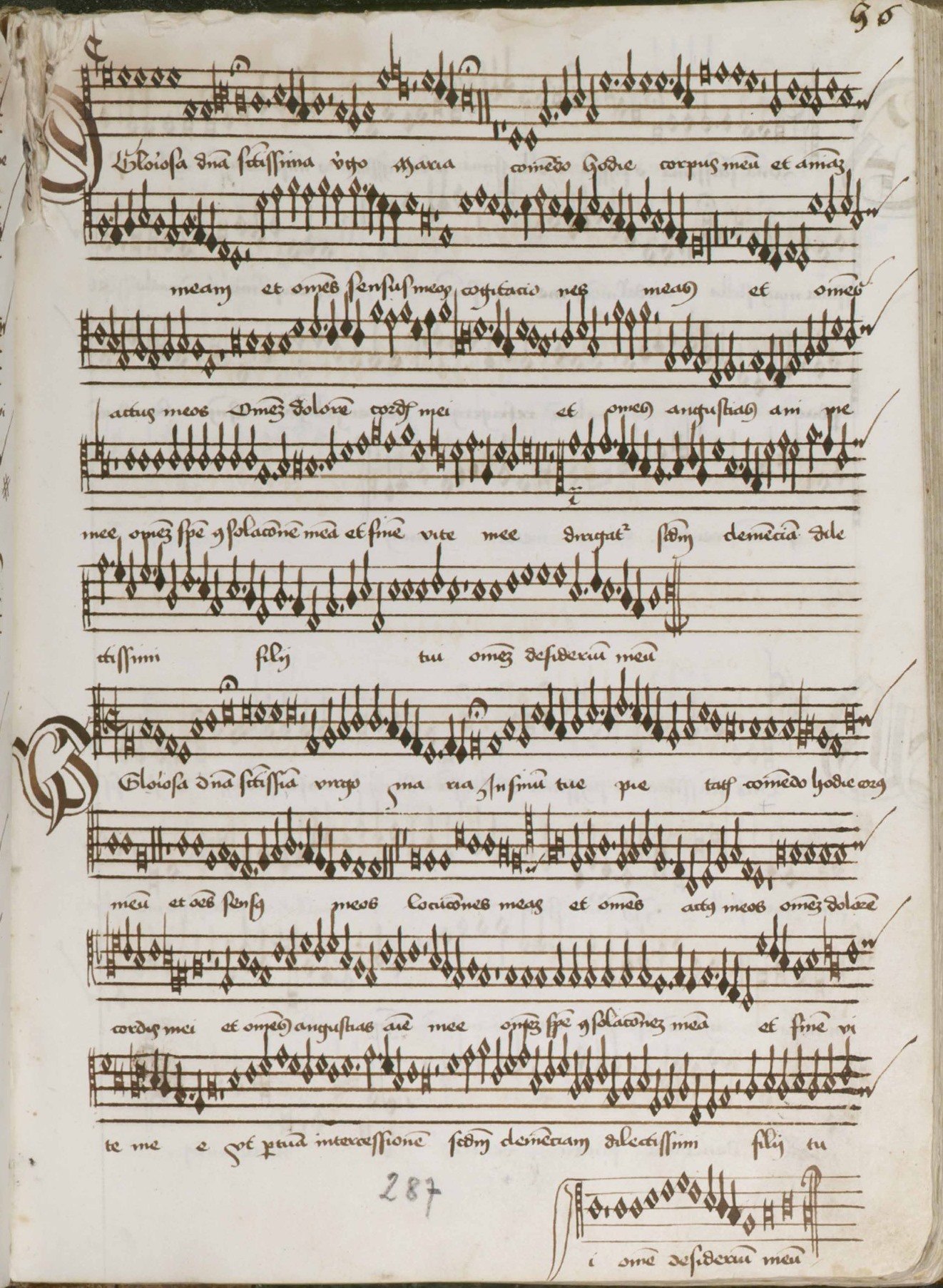

The most important Utraquist collection of polyphony called the Speciálník Codex (» CZ-HKm Ms. II A 7) originated in the last decades of the fifteenth century (c. 1485–1500), most probably in Prague. The manuscript comprising 307 paper folios of the size 375x275 mm, whose contemporary name means a special collection of repertory different from standard liturgical books, is the oldest-known testimony of various kinds of polyphony cultivated within the Utraquist church. Its main scribe, who started collecting music in the 1480s, seems to have been interested in creating a systematic collection of polyphonic music for the Mass liturgy (mass ordinary settings, motets, songs). The contents include Franco-Flemish polyphony composed between the 1440s and the 1470s (originating in the Low Countries, France, the Holy Roman Empire or Italy)[27] as well as compositions by local authors written in this style (with Latin and Czech texts) – next to the archaic repertory. This selection of music suggests that the collection was planned from the outset as a treasury of musical repertory to be used in an unknown Prague church, which had a Latin school and, later, a brotherhood of litterati as well. The Speciálník Codex shares several features with contemporary sources originating at the end of the fifteenth century in the neighbouring German-speaking regions (Bavaria, Saxony, Silesia).[28] Yet unlike these collections of exclusively contemporary music originating from the 1470s onwards,[29] the Speciálník Codex is partly a source of retrospective character. This could be owed to the demand of musical repertory at a newly-founded institution; we may also think of the above-mentioned redaction of polyphonic repertory within the Utraquist church, which probably took place in the 1470s or 1480s. This connection with the tradition of the archaic repertory can be shown mostly by the shared order of compositions.[30] The main scribe, however, also copied compositions by Franco-Flemish musicians active in the 1470s at the ducal court of Milan, some of them preserved in the Bohemian source only.[31] They are eloquent examples of a lively interest of Utraquist intellectuals in recently composed music and of contacts with important musical centres abroad. A work representing the modern repertory in the Speciálník Codex is the beautiful motet O gloriosa domina (» Hörbsp. ♫ O gloriosa domina, Ghiselin; » Abb. O gloriosa domina, Speciálník) by Johannes Ghiselin alias Verbonnet, whose career may never have taken him to Bohemia; he was active in Italy from 1491 until at least 1505 (Florence, Ferrara, Mantua) and can have been connected to Isaac.

Within the “modern” repertory (i. e. music composed in the style of Franco-Flemish polyphony) that is preserved in the Speciálník Codex, we also find several compositions of unquestionable Bohemian origin. These are latin cantiones, polyphonic settings of originally monophonic tunes known from older local sources, or compositions with a text in the Czech language. Even the oldest known song in Czech, the cantio Svatý Václave (Saint Wenceslas), appears here in a three-part polyphonic setting to the words Náš milý svatý Václave (Our dear Saint Wenceslas), with the cantus firmus quoted in the tenor voice and a virtuoso accompaniment of the two newly-composed outer voices.[32]

Until today, no documents have been found about any activity of a professional music ensemble (e. g. a court chapel) in Bohemia in the second half of the fifteenth century. A payment made at Regensburg in 1481 to „the singers of the King of Bohemia“ is ambiguous as there were two kings: Matthias Corvinus, who then controlled Northern and Eastern parts of the country, and Wladislas Jagiello, who ruled over central Bohemia.[33] As regards performers of polyphonic repertories, we can think most probably about pupils and teachers of Latin schools or their graduates: educated and leading citizens, who formed the lay ensembles called the brotherhoods of litterati since the end of the fifteenth century.[34] The Speciálník Codex was copied by more than 30 scribes,[35] so that the manuscript was until recently interpreted as a source written for an unknown Prague brotherhood of litterati. But the dating of the codex and its content (at least in the older fascicles) rather connect it with an unknown Latin school, which needed a repertory suitable for celebrating the Mass liturgy, sung by pupils and their teachers.[36] The brotherhoods of litterati consisted of adult men only: thus they could sing polyphonic music composed for voices of the same range only, which was designated as sociorum or ad voces aequales, but not any repertory written for a mixed ensemble with high discants (i. e. boys voices). The oldest sources documenting the existence of the litterati brotherhoods originated around 1490, which corresponds with the dating of the repertory ad voces aequales in the younger fascicles of the Speciálník Codex.

The existence of the Utraquist church as an alternative to the Catholic one significantly influenced the content of the music manuscripts, where we have found several features that are typical for the musical culture of Bohemia. On the other hand, it is clear today that the Utraquist church did not hinder the penetration of new compositions from a Catholic milieu: contemporary compositional techniques were even reflected in pieces of local origin. The multi-layered content of the manuscript sources shows that, beside the everpresent plainchant, the specific tradition of liturgical music in Bohemia incorporated songs and motets, which originated in the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth centuries. At the same time, we encounter compositions of “modern” European composers of the time, such as Johannes Puillois, Johannes Tourout, Walter Frye, John Bedyngham or Antoine Busnoys, whose music was well known in Central Europe since around 1460.[37] The “modern” repertory also consists of early compositions by Josquin des Prez and his contemporaries such as Isaac and Ghiselin, which appeared in European sources during the 1480s and which reached Bohemia and other central European regions very early, probably from Italy.[38]

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 2775.

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[19] Mráčková 2014, 57 ff.

[21] Strohm 1993, 513.

[22] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 263 f., 517.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.

Baťa/Kroupa/Hlávková-Mráčková 2011 | Benthem 2009 | Brewer 1984 | Bridgman 1960 | Černý 1975 | Černý 1984 | Černý 1989 | Černý 1993 | Gancarczyk 2001 | Gancarczyk 2005 | Gancarczyk 2014 | Hlávková-Mráčková 2006 | Hlávková-Mráčková 2011 | Hlávková 2012 | Hlávková 2013b | Hlávková 2014 | Hlávková 2016 | Horyna 1984 | Horyna 2004 | Just 1975 | Kolár 2005 | Lébl 1989 | Mráčková 2004 | Mráčková 2009b | Mráčková 2010 | Mráčková 2012 | Mráčková 2013 | Petrusová 1996 | Petschek 1959 | Plamenac 1960 | Rothe 1984 | Staehelin 2001 | Strohm 2012 | Szendrei 1988 | Vlhová-Wörner 2004 | Vlhová-Wörner 2006 | Ward 2001 | Žůrek 2011

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Lenka Hlávková: “Sources of Polyphony in the Bohemian lands c. 1470–c. 1500 ”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/sources-polyphony-bohemian-lands-c-1470-c-1500> (2016).