The Strahov Codex: dating and contents

It is in the second half of the fifteenth century that important collections of Franco-Flemish polyphony originated in Bohemia (Strahov Codex: » CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47, Speciálník Codex: » CZ-HKm Ms. II A 7). These are testimonies of a lively interest of both Catholic (Strahov Codex) as well as Utraquist intellectuals (Speciálník Codex) in the polyphonic music of their time, as they include pieces written by local composers together with compositions imported from different regions of Latin Europe. Because of a lack of sources it is hard to say when and how far Franco-Flemish polyphony penetrated the Catholic milieu in Bohemia. The Prague archdiocese had no archbishop for several decades, and there were many young men on the road abroad (mostly to Italy) to receive the ordination, as well as many students to receive their degrees or just to study outside Prague.[6] We can therefore assume at least some individual knowledge of contemporary polyphony before the 1460s, when the collection known as the Strahov Codex (c. 1467–1470) was compiled.[7] The manuscript of a modest „travel“ size (215 x 150 mm), but at the same time an impressive volume (614 pages) is a Catholic source of almost 300 polyphonic compositions.[8] These are systematically organised according to their liturgical function as follows: introits, Mass ordinary settings, motets, songs, hymns and Magnificats. The repertory is partly known from other contemporary Central European music collections (e. g. the later Trent Codices, the Schedel Songbook, the Nicolaus Leopold Codex),[9] but more than half of the copied pieces are transmitted in this manuscript only. The Strahov Codex is an important source of music by leading fifteenth-century composers as Guillaume Du Fay, Johannes Puillois, Johannes Cornago or Walter Frye. At the same time we find there compositions by less known or unknown authors, such as Standley, Philippus Francis or Flemmik. In terms of quantity, the leading figure within the repertory of the Strahov Codex is undoubtely the composer Johannes Tourout. Although his music was already known to musicologists more than 100 years ago, his identity and his connections to Central Europe were discovered only recently.[10]

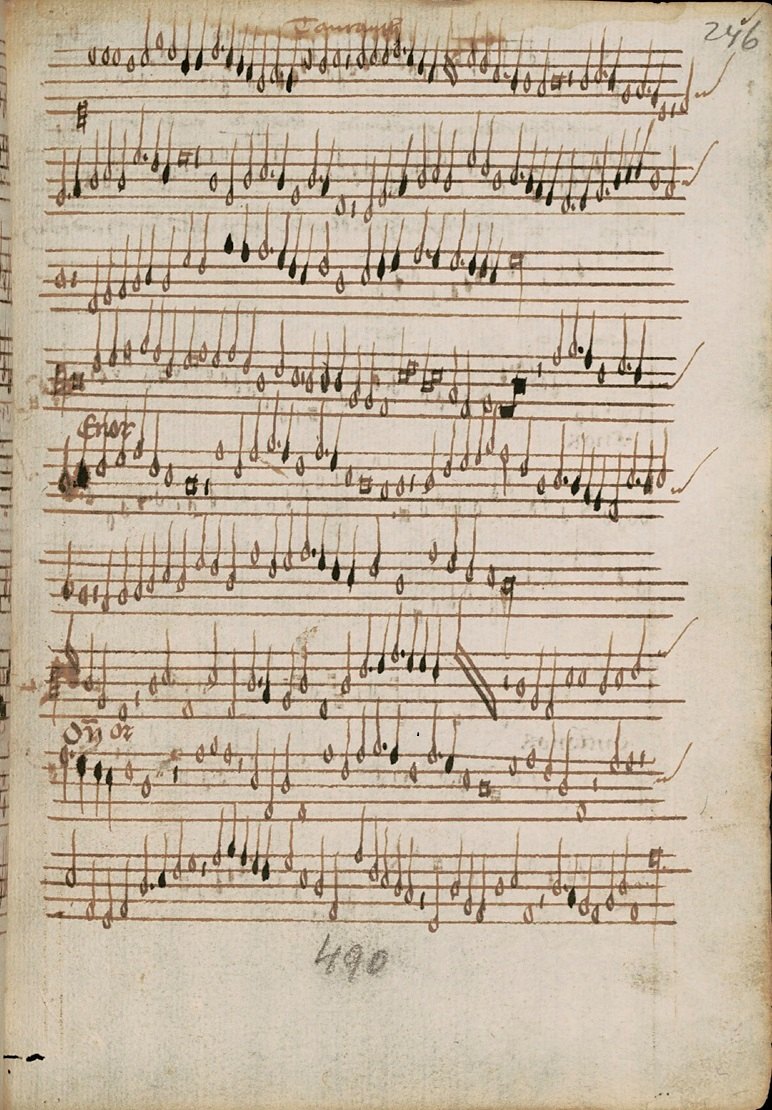

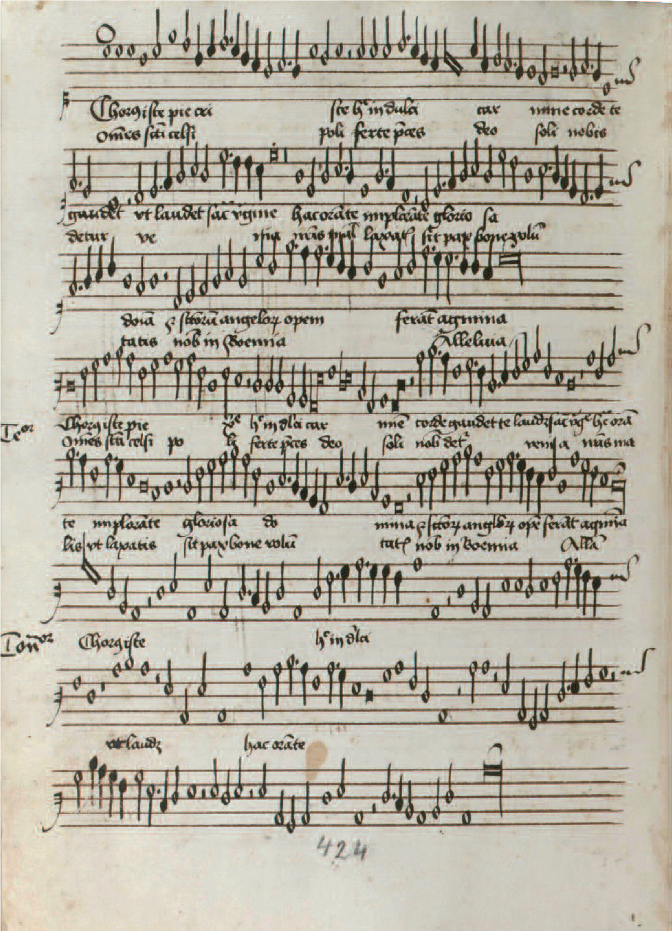

Johannes Tourout was a cleric from the diocese of Tournai (from the town of Torhout?) and he was born most probably around 1430. Given the scarcity of sources documenting his life, we can only assume that he received a high-quality music training in an important church centre of that region (Antwerp?). By 1460 he was cantor et familiaris of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III (1415−1493) , but there is no information concerning the beginning of his service at the imperial court.[11] Even so, it is evident that he reached Central Europe as an experienced composer, familiar with all forms of Franko-Flemish polyphony of that time. The oldest sources containing compositions by Tourout originated around 1460; these are the Trent Codices » I-TRbc 88 and » I-TRbc 89, the Schedel Songbook and the Buxheim Organ Book.[12] The dating of these manuscripts helps us, in connection with the testimony given by the single biographical document, to establish an approximate terminus post quem for the composer’s activity in Central Europe. Apart from compositions attributed directly to Johannes Tourout in fifteenth-century musical sources,[13] there are several anonymous masses, motets and songs composed probably by this author as well.[14] The Strahov Codex is one of the most important manuscripts in this respect, containing around 30 polyphonic songs, mostly unique chansons, which were originally settings of French poetry composed by Tourout or by musicians from his circle, but are preserved here without text or with a new Latin one. The recently discovered document on the relationship of this Flemish composer to Central Europe is of key importance for the discussion of the origin and function of the Strahov Codex. An oft-cited work by Tourout has been copied without words in the Strahov Codex (» Abb. Chorus iste, Strahov), but somewhat later with the Latin text Chorus iste in the Speciálník Codex (» Abb. Chorus iste, Specialník). This composition may well have originated as a French-texted chanson, to judge by its form.[15]

The contrafactum Chorus iste is a prayer text, which at the end invokes peace for the members of a church choir in Bohemia (“sit pax bone voluntatis nobis in Bohemia”):[16]

Chorus iste, pie Christe,

Hoc in dulci carmine

Corde te gaudet ut laudet

Sacerdotem virgine.

Omnes sancti celsi poli

Ferte preces deo soli

Nobis detur venia.

Hac orante implorante

Gloriosa domina

Et sanctorum angelorum

Opem ferant agmina,

Nostris malis ut laxatis

Sit pax bone voluntatis

Nobis in Bohemia.

Alleluia.

(This chorus, merciful Christ, is joyous at heart to praise with this sweet song you, the priest, through the virgin. All you Saints of the high heavens, bring your prayers before God alone, that mercy be given to us. May she, the glorious mistress, pray and plead, and the heavenly hosts assist, so that our wrongdoings are remitted and peace of good will is given to us in Bohemia. Alleluia.)

The concept and content of the Strahov Codex can be easily compared with the younger Trent Codices (I-TRbc 88 –91) or the oldest fascicles of the Nicolaus Leopold Codex. These collections of polyphony connected with activities of teachers of the cathedral school in Trent or with the Habsburg court in Innsbruck arguably transmit part of the repertory of the imperial chapel.[17]

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[8] For the contents of the source see the catalogue in Snow 1968.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[10] Gancarczyk 2006; Staehelin 2006; Gancarczyk 2013a; Benthem 2015.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3725

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[17] Strohm 1996; Strohm 1998; Noblitt 1987–1996; Gancarczyk 2011.

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 2775.

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[19] Mráčková 2014, 57 ff.

[21] Strohm 1993, 513.

[22] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 263 f., 517.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.