The Speciálník Codex

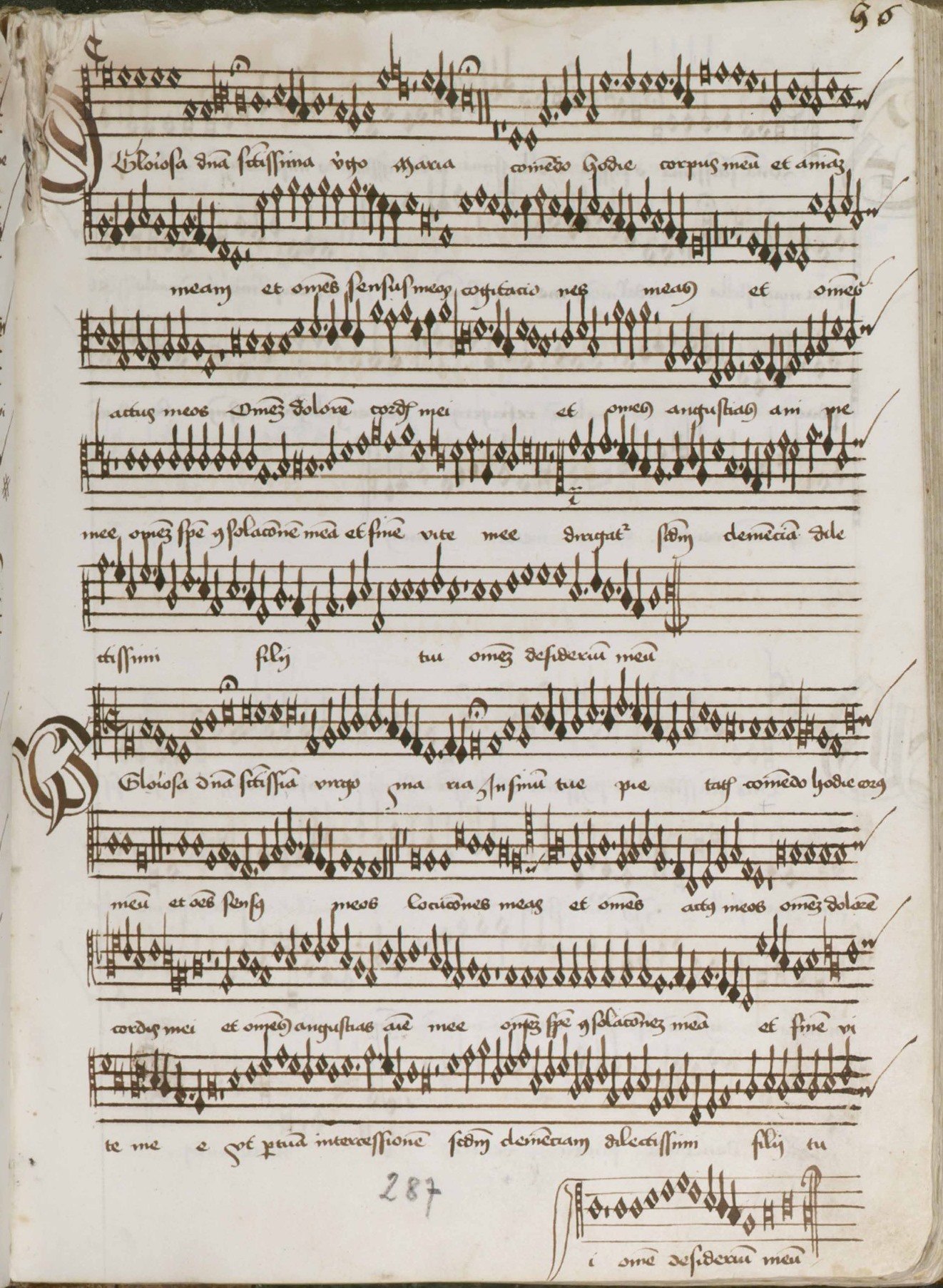

The most important Utraquist collection of polyphony called the Speciálník Codex (» CZ-HKm Ms. II A 7) originated in the last decades of the fifteenth century (c. 1485–1500), most probably in Prague. The manuscript comprising 307 paper folios of the size 375x275 mm, whose contemporary name means a special collection of repertory different from standard liturgical books, is the oldest-known testimony of various kinds of polyphony cultivated within the Utraquist church. Its main scribe, who started collecting music in the 1480s, seems to have been interested in creating a systematic collection of polyphonic music for the Mass liturgy (mass ordinary settings, motets, songs). The contents include Franco-Flemish polyphony composed between the 1440s and the 1470s (originating in the Low Countries, France, the Holy Roman Empire or Italy)[27] as well as compositions by local authors written in this style (with Latin and Czech texts) – next to the archaic repertory. This selection of music suggests that the collection was planned from the outset as a treasury of musical repertory to be used in an unknown Prague church, which had a Latin school and, later, a brotherhood of litterati as well. The Speciálník Codex shares several features with contemporary sources originating at the end of the fifteenth century in the neighbouring German-speaking regions (Bavaria, Saxony, Silesia).[28] Yet unlike these collections of exclusively contemporary music originating from the 1470s onwards,[29] the Speciálník Codex is partly a source of retrospective character. This could be owed to the demand of musical repertory at a newly-founded institution; we may also think of the above-mentioned redaction of polyphonic repertory within the Utraquist church, which probably took place in the 1470s or 1480s. This connection with the tradition of the archaic repertory can be shown mostly by the shared order of compositions.[30] The main scribe, however, also copied compositions by Franco-Flemish musicians active in the 1470s at the ducal court of Milan, some of them preserved in the Bohemian source only.[31] They are eloquent examples of a lively interest of Utraquist intellectuals in recently composed music and of contacts with important musical centres abroad. A work representing the modern repertory in the Speciálník Codex is the beautiful motet O gloriosa domina (» Hörbsp. ♫ O gloriosa domina, Ghiselin; » Abb. O gloriosa domina, Speciálník) by Johannes Ghiselin alias Verbonnet, whose career may never have taken him to Bohemia; he was active in Italy from 1491 until at least 1505 (Florence, Ferrara, Mantua) and can have been connected to Isaac.

Within the “modern” repertory (i. e. music composed in the style of Franco-Flemish polyphony) that is preserved in the Speciálník Codex, we also find several compositions of unquestionable Bohemian origin. These are latin cantiones, polyphonic settings of originally monophonic tunes known from older local sources, or compositions with a text in the Czech language. Even the oldest known song in Czech, the cantio Svatý Václave (Saint Wenceslas), appears here in a three-part polyphonic setting to the words Náš milý svatý Václave (Our dear Saint Wenceslas), with the cantus firmus quoted in the tenor voice and a virtuoso accompaniment of the two newly-composed outer voices.[32]

Until today, no documents have been found about any activity of a professional music ensemble (e. g. a court chapel) in Bohemia in the second half of the fifteenth century. A payment made at Regensburg in 1481 to „the singers of the King of Bohemia“ is ambiguous as there were two kings: Matthias Corvinus, who then controlled Northern and Eastern parts of the country, and Wladislas Jagiello, who ruled over central Bohemia.[33] As regards performers of polyphonic repertories, we can think most probably about pupils and teachers of Latin schools or their graduates: educated and leading citizens, who formed the lay ensembles called the brotherhoods of litterati since the end of the fifteenth century.[34] The Speciálník Codex was copied by more than 30 scribes,[35] so that the manuscript was until recently interpreted as a source written for an unknown Prague brotherhood of litterati. But the dating of the codex and its content (at least in the older fascicles) rather connect it with an unknown Latin school, which needed a repertory suitable for celebrating the Mass liturgy, sung by pupils and their teachers.[36] The brotherhoods of litterati consisted of adult men only: thus they could sing polyphonic music composed for voices of the same range only, which was designated as sociorum or ad voces aequales, but not any repertory written for a mixed ensemble with high discants (i. e. boys voices). The oldest sources documenting the existence of the litterati brotherhoods originated around 1490, which corresponds with the dating of the repertory ad voces aequales in the younger fascicles of the Speciálník Codex.

The existence of the Utraquist church as an alternative to the Catholic one significantly influenced the content of the music manuscripts, where we have found several features that are typical for the musical culture of Bohemia. On the other hand, it is clear today that the Utraquist church did not hinder the penetration of new compositions from a Catholic milieu: contemporary compositional techniques were even reflected in pieces of local origin. The multi-layered content of the manuscript sources shows that, beside the everpresent plainchant, the specific tradition of liturgical music in Bohemia incorporated songs and motets, which originated in the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth centuries. At the same time, we encounter compositions of “modern” European composers of the time, such as Johannes Puillois, Johannes Tourout, Walter Frye, John Bedyngham or Antoine Busnoys, whose music was well known in Central Europe since around 1460.[37] The “modern” repertory also consists of early compositions by Josquin des Prez and his contemporaries such as Isaac and Ghiselin, which appeared in European sources during the 1480s and which reached Bohemia and other central European regions very early, probably from Italy.[38]

[28] Several of them are discussed in Just 1981.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.

[38] See Just 1981; Wieczorek 2002; » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

Baťa/Kroupa/Hlávková-Mráčková 2011 | Benthem 2009 | Brewer 1984 | Bridgman 1960 | Černý 1975 | Černý 1984 | Černý 1989 | Černý 1993 | Gancarczyk 2001 | Gancarczyk 2005 | Gancarczyk 2014 | Hlávková-Mráčková 2006 | Hlávková-Mráčková 2011 | Hlávková 2012 | Hlávková 2013b | Hlávková 2014 | Hlávková 2016 | Horyna 1984 | Horyna 2004 | Just 1975 | Kolár 2005 | Lébl 1989 | Mráčková 2004 | Mráčková 2009b | Mráčková 2010 | Mráčková 2012 | Mráčková 2013 | Petrusová 1996 | Petschek 1959 | Plamenac 1960 | Rothe 1984 | Staehelin 2001 | Strohm 2012 | Szendrei 1988 | Vlhová-Wörner 2004 | Vlhová-Wörner 2006 | Ward 2001 | Žůrek 2011

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 2775.

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[19] Mráčková 2014, 57 ff.

[21] Strohm 1993, 513.

[22] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 263 f., 517.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.