The court chapel of Maximilian I

The research for this chapter was carried out in the context of the project The court chapel of Maximilian I: between art and politics (FWF Project Number P 28525), based at the University of Vienna. All the documents referred to in this chapter will be published in my forthcoming monograph on Maximilian’s chapel.

Maximilian as heir to the tradition of the court chapels of the Valois Dukes of Burgundy

From the time of Charlemagne, the courts of Holy Roman Emperors customarily included several priests who served the liturgical needs of the ruler. Their services did not simply satisfy the ruler’s own personal piety, but also reflected his quasi-sacral role. The term capellanus (chaplain) was originally applied to one of the clerics who served the cult of St Martin of Tours, which involved the veneration of relics of the cloak (cappa) which he was said to have shared with the beggar; the term capella was a back-formation from capellanus. Like the rest of the ruler’s personal court, the chapel was customarily dissolved at the ruler’s death.[1] Maximilian’s highly mobile court was never associated primarily with any one building. Maximilian established many liturgical foundations. Some of these funded liturgical observances were in chapels located within his residences as Archduke of Austria, particularly Innsbruck and Vienna. Others were in small and sometimes quite remote churches and chapels.

After marrying Mary of Burgundy in 1477, Maximilian took over the chapel of his late father-in-law Charles the Bold virtually intact.[2] The chapel of Maximilian and Mary included several notable musicians, including the composer Antoine Busnoys. Following Mary’s accidental death in 1482, the estates and cities of Flanders, such as Ghent and Bruges, refused to recognise Maximilian’s authority, except as regent for his son Philip the Fair, whom the Flemings considered Mary’s only legitimate heir. In the ensuing warfare, Maximilian was even imprisoned for a time by the city council of Bruges. During these difficulties, Maximilian’s court, including his chapel, was greatly reduced. However, in 1485, Maximilian restocked his chapel with several excellent singers, in preparation for his election and coronation as King of the Romans. Amongst these singers was the famous tenorist Jean Cordier, who enjoyed international fame, and the contratenor Rogier de Lignoquercu, who had previously sung in the papal chapel, and who would later serve in the Milanese court.[3] Although Maximilian had no in-house composer for over a decade after Busnoys left his service in 1483, Birgit Lodes has argued that Maximilian commissioned polyphonic music from other composers in his geographical orbit. She has suggested, for example, that he commissioned Jacob Obrecht to write the Missa Salve diva parens for his coronation (see » D. Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens). In early 1490, Maximilian sent the composer Jacobus Barbireau to Hungary on a diplomatic mission. Maximilian’s relationship with this musician was evidently one of considerable trust.[4] Such esteem may explain the strong representation of works by Barbireau in sources associated with the Burgundian Habsburg court, such as the choirbook » A-Wn Mus. Hs. 1783.

Maximilian’s chapels in Austria: foreign and local members and practices

In 1490, Maximilian took over lordship of the Tyrol, moving his court to Innsbruck and initiating a gradual hand-over of power in the Low Countries to his son Philip the Fair. Most of Maximilian’s Burgundian singers passed into Philip’s service. However, a small group, including the choirmaster Nicolas Mayoul Sr., visited Austria in 1492.[5] Maximilian soon appointed native Austrian singers to his chapel at Innsbruck, including some who had previously served in the chapel of his father, Emperor Frederick III, such as Hanns Kerner. Maximilian appointed the Flemish singer Henricus Isaac as court composer in 1497.[6] Over the next two decades, Isaac would supply music for Maximilian’s court, including polyphonic settings of the propers of mass, settings of the mass ordinary, songs, sacred motets, songs and instrumental music (» D. Isaac im Dienst von Maximilian; » I. Henricus Isaac’s Amazonas). He also contributed to the diffusion of the musical style of Maximilian’s chapel through commissions for other places, most notably the polyphonic propers he wrote for the cathedral of Constance. Decades after his death, Isaac’s settings of the propers (both for Constance and for Maximilian’s chapel) were still sufficiently prized that they were collected and printed under the title » Choralis Constantinus.

Isaac’s students further disseminated his style. Adam Rener, a native of the Low Countries who was trained in Maximilian’s chapel and presumably learned composition from Isaac, was later employed as singer and composer at the Saxon court at Torgau. Isaac’s most famous student was Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl). In an autobiographical song, Lust hab ich ghabt zur Musica, Senfl describes his training in Maximilian’s chapel under Isaac’s instruction.[7] This document provides a rare insight into a leading composer’s reflection on his own process of artistic maturation. After Maximilian’s death, Senfl edited a retrospective collection of motets from the repertoire of Maximilian’s chapel, » Liber selectarum cantionum (Augsburg: Grimm and Wyrsung, 1520).[8] This book includes several occasional pieces, such as Virgo prudentissima, written to rally support amongst the assembled estates at the Diet of Constance (1507) for Maximilian’s Italian campaign, and Optime pastor, evidently written to congratulate Leo X on his election to the See of Peter in 1513 (» D. Kap. Komponiertes Herrscherlob; » Abb. Liber selectarum cantionum).[9] Both these motets were the result of cooperation between Maximilian’s choirmaster Georgius Slatkonia, the author of the verse texts, and the composer Isaac. The text of Senfl’s Sancte pater divumque decus, a motet in honour of St Gregory included in the Liber selectarum cantionum, was almost certainly written by the distinguished humanist and poet Joachim Vadianus, professor of poetics at Vienna (» I. Hofhaimer and Joachim Vadianus). The work was commissioned by Gregor Valentinianus, another member of Maximilian’s chapel, as a votive work in praise of Gregory and indirectly of Maximilian himself, whose love of music is specifically mentioned in the text.[10] After Maximilian’s death, Senfl was appointed as singer and composer at the Wittelsbach court at Munich, which thus became a further hub for the dissemination for the repertoire and taste of Maximilian’s chapel after the emperor’s death.

Maximilian’s “foundation” of a “chapel” in Vienna

In 1498, Maximilian famously sent a group of singers, including Isaac and Rener, to Vienna to establish a “chapel”.[11] This document has long been interpreted – or rather, misinterpreted – as the “birth certificate” of the Viennese musical chapel, and ultimately of the Vienna Boys’ Choir. However, as Othmar Wesseley showed, this is a misconception: Maximilian’s chapel was dissolved at his death, and there were only a few continuities of personnel between the chapels of Maximilian and Ferdinand I.[12] Rather, as I have argued elsewhere, Maximilian’s purpose in 1498 was not to start something new, but to ensure that the pre-existent choral foundations in the castle chapel in Vienna could be serviced with due liturgical and musical propriety according to the wishes of their founders, after the disruption of Matthias Corvinus’ occupation of Vienna (1485–1490).[13] Maximilian specified that the boys sent to Vienna were to be trained in “singing descant in the Brabant style”. This mysterious phrase might refer to a particular style of improvised polyphonic singing, a particular manner of vocal production, or simply a general musical orientation towards the style of masters such as Obrecht, Josquin and of course Isaac himself. Whatever this phrase might mean, it is case clear that Maximilian wished to transplant to his Austrian dominions the kinds of cultural practices, styles and artistic levels which he had come to appreciate in the Burgundian Low Countries.

Finances

Courts were very expensive to run, and chapels could consume a significant percentage of the court’s budget. Since many singers were in clerical orders, the ruler could keep down costs by appointing singers to ecclesiastical benefices. These were church offices whose income was derived from an investment made as part of an initial foundation, often as part of a testamentary bequest. The terms of the foundation laid out the liturgical services desired by the founder. These might involve regular masses said for the soul of the founder, or votive services such as the performance of antiphons such as Salve regina. Depending on the amount of money provided in the foundation, the musical component of such benefices might involve chant, polyphony or organ. Even benefices that included no provision for music could serve the chapel, since they could be granted to singers in the ruler’s chapel, who would then appoint a vicar to carry out the liturgical requirements of the foundation while sharing its income with the cleric-singer who held the benefice.

The initial foundations specified who had the right to present candidates for each benefice to the relevant ecclesiastical authority (generally bishops or the heads of religious houses); these authorities generally, though not inevitably, endorsed the ruler’s candidate. Since rulers had the resources to establish many well-endowed foundations, their heirs accumulated the right of presentation to ever-growing numbers of benefices. As heir to many territories, Maximilian had the right of presentation to hundreds of benefices. He could therefore use the promise of promotion to ever more lucrative, prestigious or convenient benefices to promote singers within his chapel. His presentation of the Slovene Georgius Slatkonia as Bishop of Vienna was simply one extreme of a series of finely graded ecclesiastical appointments that lay in Maximilian’s hands.[14] There is much documentary evidence that Maximilian was personally involved in the presentation of his chaplains to various benefices, thus positioning himself as ultimate source of patronage. Beside the basic income from benefices, members of the chapel received money for the expenses associated with their attendance at court on its travels.

Members of the chapel who were not clerics had to be paid directly from the budget of the court, though they were sometimes appointed to positions in the imperial administration, such as toll-collectors; in such cases they evidently appointed representatives who carried out the everyday business associated with the appointment, analogous to clerical vicars. Secular members of the chapel might also be rewarded in kind, such as housing, or supplies of firewood, fish, butter, wine, meat or cloth. When Maximilian seized territory in the Veneto in 1510, he distributed parcels of land to several members of his chapel, such as Isaac, Georg Vogel and Sigmund Vischer.[15]

Choirboys under Maximilian

We know little about the recruitment of choirboys for Maximilian’s chapel. A few were the sons of adult singers in the chapel. For example, the choirboy Georg Täschinger, listed as a member of Maximilian’s chapel at his death, was the son of the chaplain and tenorist Michael Täschinger, ordained to the priesthood after the death of his wife; but such cases were rare.[16] Other choirboys were the sons of members of the court. It has been suggested that the poor Swiss boy presented at court in 1498 because of his skill as a singer was probably Ludwig Senfl.[17] The choirboys evidently learned the musical skills necessary for performing chant and polyphony in the divine service. Besides training in composition, some also learned to play the organ from Maximilian’s famous court organist Paul Hofhaimer. As early as 1488, when Hofhaimer was still in the service of Sigmund of the Tyrol, it seems that two organ students lived with him.[18] This was certainly the case when Hofhaimer spent periods at the Saxon court at Torgau in 1516 and 1518.[19] While the court was in residence at Innsbruck, the boys attended the school attached to St James’s parish church, which served as the court church.[20] While the court was on progress, the boys’ lessons were probably taken over by another member of the chapel. Choirboys also learned court etiquette and made contacts with other members of the ruling élite, which could prove invaluable if the boys returned to imperial service as adults.

After their voices broke, the choirboys customarily received a scholarship to the University of Vienna, generally for three years, though this could be extended if a boy showed particular aptitude for learning and wished to study in one of the higher faculties after taking his basic degree in the Arts Faculty. Some boys subsequently returned to imperial service, a few as singers, most as toll-collectors, accountants or secretaries in the chancery.

Size and constitution of the chapel

While the Burgundian court kept daily records of the attendance of the members of the court as a basis for their payment, no such detailed lists have survived for Maximilian’s Austrian court. At best we have records of payment for individual occasions, or for longer stretches of activity, often quarterly payments. While the list of Maximilian’s court drawn up after his death includes nine chaplains, about twenty adult singers and as many boys, this evidently represents a pool of people who could be drawn upon for individual occasions:

Statt des Hoffgesindts/ so nach absterben der Khay: Matt: &c. Hochlöblicher gedachtnus zw Welß Im Monat Januarj des .1519. Jar gemacht worden ist/ Wie hernach volgt.

[… 4r]

Caplan.

Herr Eberhardt Sennfft

Herr Sixt Rantzmeser

Herr Hanns Brüelmaÿr

Her Thoman Khrieger

Herr Wilhalmb Waldtner

Herr Caspar Höltzel

Herr Cristof Langkutsch

Herr Erhardt Almauer

Herr Conradt Groß

Andree Pranndtner Meßner[… 9v]

Tenoristen

Gregorius Valentinan Capeln Verweser

Lienhardus Acot

Michel Taschinger

Melchior Eisenhert

Mathias Rauber

Hannß CabaÿBassisten

Georg Paumhäckhl

Caspar Purckher

Priamus Juras

Nicodemus Kulwagner

Petrus Seepacher

Bartholome Töbler [10v]Altisten

Gregorius Vogl

Sigmundus Vischer

Ludouicus Sennftl

Lucas Wagenrieder

Georgius Baßitz

Johannes Anger

Herr Hanns VischerSinger Knaben

Ludouicus Gitterhofer

Georgius Peigartsamer

Johannes Pantzer

Petrus Staudacher

Matthias Plaser

Bartholomeus Merßwanger

Balthasar Aster

Nicolaus Schinkho

Martinus Heutaller

Lucas Tillger

Laurentius Wagner

Gerhardus Mell

Rupertus Frueauf

Sebastianus Slauerspach

Bartholomeus Raichensperger

Martinus Alfantz

Hainricus Friesenberger [11r]

Georgius Teschinger

Georgius Stoltz

Sebastianus Gstalter

Ruepertus HungerList of the members of Maximilian’s chapel, drawn up after his death in 1519. Vienna, HHStA, OMeA SR 181/3.[21]

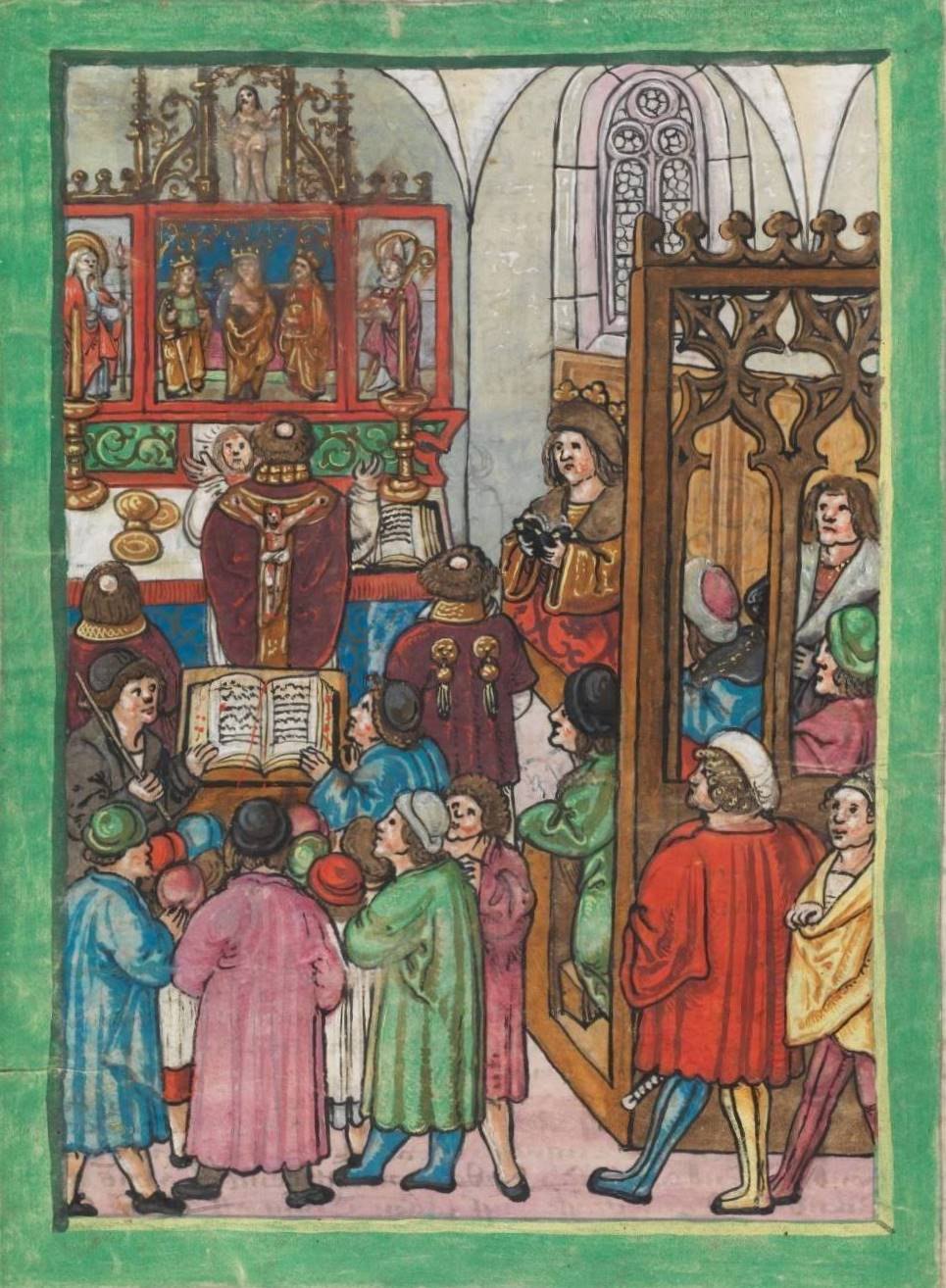

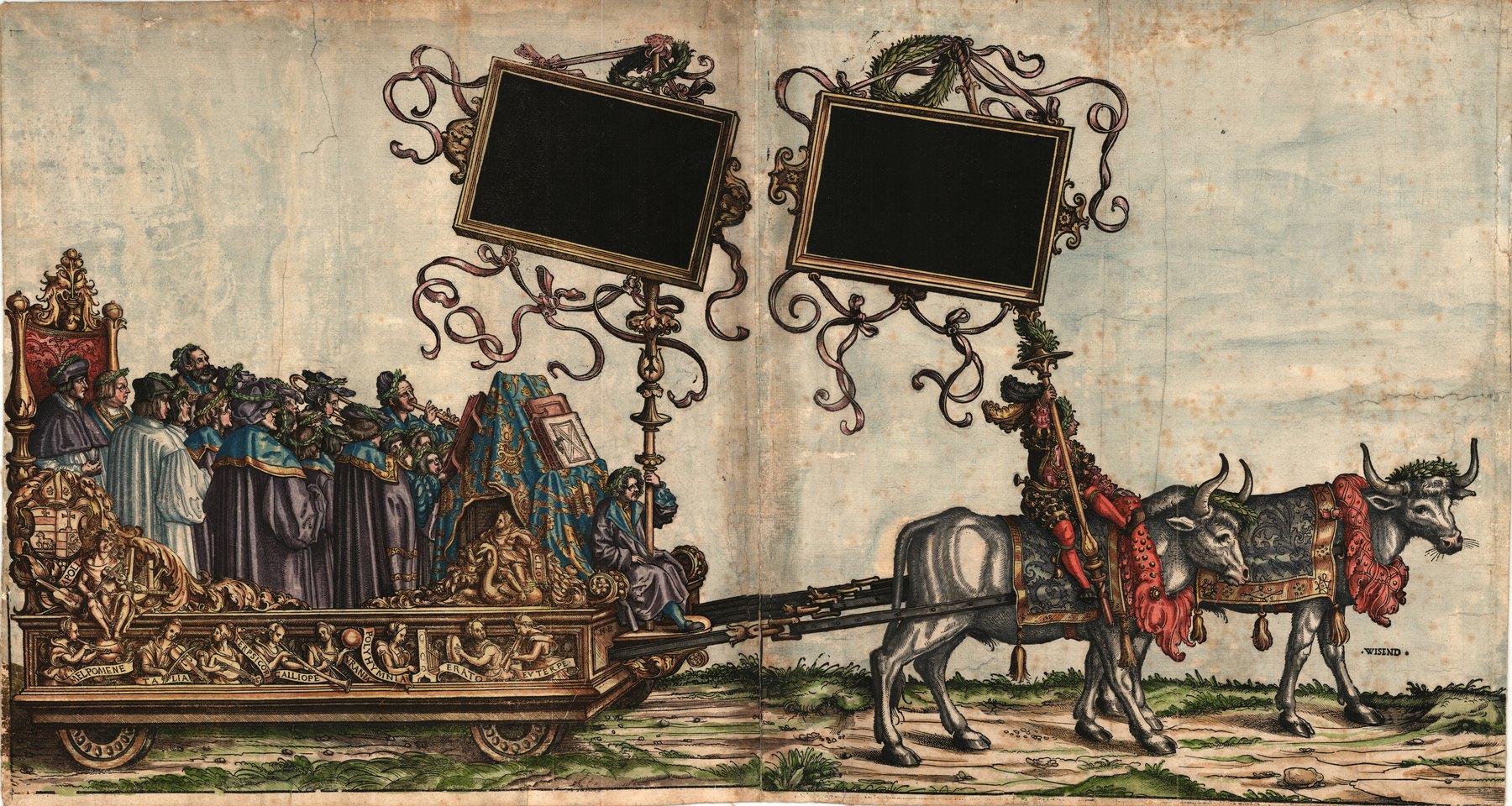

Iconographical representations of Maximilian’s chapel suggest that performing ensembles consisted of five to eight men, and four to six boys: see » Abb. Maximilian I. im Dom zu Konstanz.

Such sizes suggest that the lower voice-parts were largely doubled, while the upper ones were sung by three or four boys apiece. Iconographical and other archival evidence suggests that some or all of the voices were sometimes doubled by trombones and cornetto: see » Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.

The singers of the chapel are sometimes mentioned as performing with organ (» Instrumentenmuseum Orgel, Portativ]. The evidence suggests strongly that the organ was not used at this time to double the voices (colla parte), but played in alternation with the voices, improvising over a chant model. The organ could also be used to reinforce the cantus firmus in vocal polyphony, as can be deduced from A-Wn Cod. 5094.[22] Since written polyphony was performed from parts (either in separate books or in a choirbook), colla parte performance would require an organist either to memorise a piece of written polyphony, or to write it out in keyboard score; since no such keyboard scores have survived from this period, it is likely that organists did not routinely accompany colla parte except by reinforcing a cantus firmus, as mentioned above. The transcriptions of vocal originals in the surviving organ tabulatures from the early sixteenth century, such as those of Hans Buchner, Leonhard Kleber and Fridolin Sicher, were evidently intended as solo pieces rather than as accompaniments, since they include only extracts from larger works, depart in some details from the vocal originals, or include such a high degree of ornamentation as to render them unsuitable as accompaniment (see » C. Kap. Gebrauch und Missbrauch der Orgel).

Conclusion: the international outlook

Maximilian’s chapel was an international body which comprised at different times members from across Europe, from the Low Countries to modern Slovenia. Although there was only limited transfer of personnel between Maximilian’s chapel as it existed during his time in the Low Countries and that which he built up in Austria, the musical sources associated with Maximilian’s Austrian court show a distinct preference for the music of French and Flemish composers, a taste already discernible in the chapels of the earlier Habsburg Kings Albrecht II and Frederick III.[23] Maximilian’s explicit instruction that the boys he sent to Vienna in 1498 in the care of Hanns Kerner and Henricus Isaac were to learn the art of Brabantine singing is consistent with this preference for Franco-Flemish polyphony, which was fed by ongoing links to the chapels of Maximilian’s children Philip the Fair and Margaret of Austria. Maximilian’s chapel also served as an important centre for the training of boys whose musical skill, education and close connections with the ruling élite of the empire prepared them for service in the imperial court and administration in adulthood.

[2] See Fiala 2002.

[3] On Lignoquercu’s career at Milan, see Merkley/Merkley 1999, 7, 101–102, 125, 141, 152, 177, 179–180, 242, 251, 285, 288, 290, 293, 296, 371, 373, 376, 391 (here called Ruglerius Lignoquerens).

[4] Wien, HHStA, RK Maximiliana 1 (alt 1a), Konv. 6, 1r–v. Further, see Kooiman/Carr/Palmer 1988. The importance of interpersonal relationships at court has been highlighted in recent historical work; notably, see Hirschbiegel 2015.

[5] Innsbruck, TLA (A-Ila), oö Kammerraitbuch 32 (1492), 30r. Further on court music at Innsbruck in these years, see » I. Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck.

[6] Innsbruck, TLA, Urkunde I 5147/2. Further, see Schwindt/Zanovello 2019.

[7] » A-Wn Mus. Hs. 18810, Tenor, 37r–38v; further, see Gasch 2010.

[9] Alberto Pio da Carpi to Maximilian, 25 June 1513, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Library (US-PHu), Special Collections Ms. Coll. 637, folder 2, 6r–v. Further, see Jacoby 2011. Pietschmann 2019 argues that this motet was written rather for Matthaeus Lang’s entry to Rome in 1514, though this hypothesis seems less likely in the light of the report from Carpi.

[10] See Schlagel 2002, 574–577.

[11] Vienna, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (FHKA), AHK SB Gedenkbuch [GB] 17, fol. 349r (377r).

[12] Wessely 1956, 121.

[13] McDonald 2019, 21–22.

[14] McDonald 2019, 11.

[15] Wien, HHStA (A-Whh), Reichsregistraturbuch PP 17v–18r; transcr. in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 69–70.

[16] Täschinger’s first mass is mentioned in Wien, HHStA (A-Whh), Reichsregistraturbuch AA, 66v–67r; he describes his personal history in a letter addressed apparently to the government of Ferdinand I, now Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Mus.ep. Arigoni, F. Varia 1 (20).

[17] Wien, FHKA AHK GB 4, 111r (135r); Gasch 2015, 368–369.

[18] Innsbruck, TLA (A-Ila), Hs.113, 94r (Nota wen man Speisn sol): “Zwen knaben bej Maister Paulsen.”

[19] Weimar, Thüringisches Landesarchiv, EGA, Reg. Rr. S. 1–316, nº 737, 1a r–v; EGA, Reg. Aa 2991–2993, 10r–11v; further, see Aber 1921, 75.

[21] See Koczirz 1930/31. For online images, see https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=11; https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=12

[22] » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs. On alternatim uses of the organ in the liturgy, see Rabe 2019.

[23] See » D. Kap. Zur musikalischen Quellenlage der Hofkapelle Maximilians; » D. Hofmusik Innsbruck. In the sources discussed there, repertory from Flemish composers is well present. See also » F. Musiker aus anderen Ländern.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Grantley McDonald : “The court chapel of Maximilian I”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/court-chapel-maximilian-i> (2019).