“Musica Lauten und Rybeben”: Lutes and String Instruments

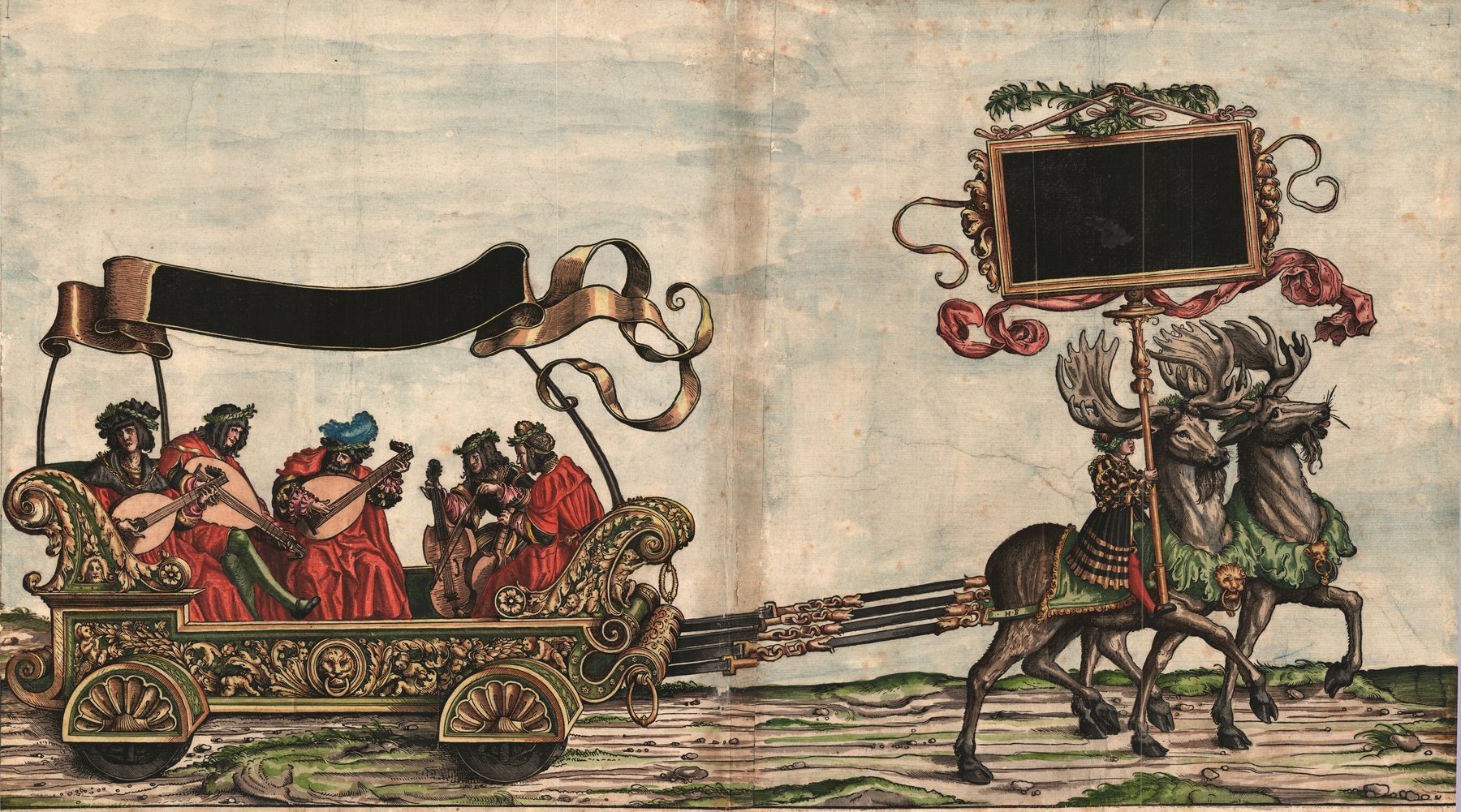

In the Triumphzug, following somewhat after the pipers and drummers, comes the first musician carriage, titled “Music: lutes and viols” (» Abb. Triumphzug Lauten), aon which five musicians are seated, playing three different-sized lutes and two larger string instruments. These vertically held instruments can be described as violas da gamba, known at Maximilian’s court as “Ribebe.” This name is derived from the Arabic rebab (or rabāb) and was used primarily in Italy to refer to a larger string instrument. In any case, it is a loanword, associating the instrument with foreign origins; however, these instruments differ visually from contemporary Italian representations. The “Maister,” or the most distinguished of these musicians, is a certain Artus, likely the older man in the middle of the carriage. This Artus was actually named Albrecht Morhanns, but he was known as Artus von Enntz Wehingen.[15] Born around 1460, he participated in the famous pilgrimage of Baron Werner von Zimmern to the Holy Land in 1483 as a serf, tasked with the duties of a barber and lutenist. Maximilian specifically sought to bring him into his retinue due to his exceptional skills as a lutenist, and in 1489, he was freed from serfdom “for the sake of his artistic suitability and gracious inclination.” Subsequently, Artus is documented as “the lute player of the Roman king,” often mentioned alongside a second lutenist with whom he apparently performed as a duo.[16] Such a lute duo is well-documented in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries: one player, known as the “tenorista,” played the tenor or provided a sonic framework (for example, of a song, motet, or basse danse), while the other player, the “discantista,” improvised over it. A hallmark of this playing style is the use of a plectrum, such as a quill, enabling particularly swift and virtuosic runs.[17]

One of the younger musicians on the same carriage could be Adolf Blindhamer (c. 1480–before 1532), who is documented as a lutenist at the court for the first time in 1503.[18] He retained the title “lutenist to His Imperial Majesty” (“lawtenslaher kays. Mt”) until the death of Maximilian, although in 1514 he was received as a citizen in Nuremberg to teach “the young people on the lute and other instruments.” Particularly significant is that a manuscript with compositions and arrangements for the lute by Blindhamer has been preserved, providing insight into the concrete music of the lutenists at Maximilian’s court (see the chapter “Lautenintabulierungen von Adolf Blindhamer”). This reveals a polyphonic playing style, where multiple voices are plucked simultaneously with the fingers.

The lutes and “Rybeben” were likely played by the same musicians, as the lute and viol were long considered related or similar instruments, as evidenced by the earliest instructional books for these instruments, such as those by Hans Judenkünig (Vienna 1523) or Hans Gerle (Nuremberg 1532), and as suggested by the similar setup of the strings, frets and tuning. It has been speculated that the mention of three to four “geyger” of the emperor (first noted in 1515) refers to an ensemble of such viols, as documented at Italian courts at the same time.[19] However, this must remain speculative, as besides the vague designation “geyger to His Imperial Majesty” (“kay. Mt. Geygern”) only the names of the players are known (Caspar and Gregor Egkern, Jorigen Berber, and Heronimus Hager), but nothing about their instruments. Caspar Egkern appears a few years earlier also as “trombonist to His Imperial Majesty” (“Kay. Mayt. busaner”) or “piper to His Imperial Majesty” (“Kay Mayt pfeyffer”), so he was not limited to a specific instrument.[20]

[15] See Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[16] Polk 1992, 86 (with references from Augsburg archives).

[17] See Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] See Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (including the following).

[20] According to payments in the Augsburg (D-As) Baumeisterbuch 103 (1509), fol. 24v, and 104 (1510), fol. 28; kindly communicated by Keith Polk.

[1] Zum Triumphzug, seinen unterschiedlichen Versionen und der komplexen Entstehungsgeschichte informiert Appuhn 1979 und Michel/Sternath 2012; zur Bedeutung für Maximilian Müller 1982; zum Verhältnis zwischen Abbildung und Realität Polk 1992; das Zitat stammt aus der frühesten erhaltenen Formulierung des ikonographischen Programms des Triumphzugs 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (Zitat aus den Augsburger Baumeisterbüchern von 1491, den Kassenbüchern des Rats über Ein- und Ausgaben).

[5] Vgl. Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] Vgl. Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Zitiert nach Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] Vgl. Schwindt 2012.

[10] Sie erhält im Juni 1520 bei der Auflösung der Hofkapelle nach dem Tode von Maximilian die hohe Summe von 50 Gulden „zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung“; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Wie beispielsweise „Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher“, die 1491 ausdrücklich für ihre Dienste „bei Tanz“ an der Fasnacht bezahlt werden; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] Für eine Zusammenstellung der musikrelevanten Abbildungen siehe Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] Vgl. Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[17] Vgl. Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] Vgl. Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (dort auch zum Folgenden).

[20] Laut Zahlungen in den Augsburger (D-As) Baumeisterbüchern Nr. 103 (1509), fol. 24v, und Nr. 104 (1510), fol. 28; freundliche Mitteilung von Keith Polk.

[21] Vgl. Jahn 1925, 10 ff., und Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] Vgl. Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] Vgl. Brief von Paul Hofhaimer an Joachim Vadian am 14. Mai 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So der Wortlaut in der Formulierung des ikonographischen Programms in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] Vgl. Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, Titelblatt des Tenor-Stimmbuchs; zur Datierung siehe Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] Vgl. Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] Vgl. Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; Faksimile und Beschreibung in Kirnbauer 2003. Lautentabulaturen der nächsten Generation aus dem süddeutschen Sprachraum beschreibt » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] Vgl. Moser 1966, 26 und 182, Fußnote 35.

[40] Vgl. Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; siehe auch » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Martin Kirnbauer: „Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).