Court Music and Representation

The wealth and extent of the musical representation apparatus of Emperor Maximilian I (1459–1519) is vividly illustrated in the woodcuts of the so-called Triumphzug. However, it should not be forgotten that this ambitious and costly visual project is not a realistic depiction of his court chapel but rather a highly idealized vision “zu lob vnnd Ewiger gedächtnüs” (for praise and eternal remembrance) of the reputation-conscious monarch.[1] The image frieze, which in its assembled state is over 100 metres long, includes, in addition to the carriage with the actual court chapel (titled “Musica Canterey” with the chapel master Georg Slatkonia and singers), four other carriages with musicians, not to mention a considerable number of trumpeters and drummers, “Burgundisch pfeyffer” (Burgundian pipers), as well as pipers and drummers, who are all represented in the procession. The more modest historical reality of Maximilian’s musical apparatus is reflected in the account books, such as the inventory on the occasion of the dissolution of the court chapel in 1520 after Maximilian’s death: Here, there are a total of thirteen “Trumetter vnd paugker” (trumpeters and timpanists), nineteen adult singers, about twenty boys as “Discantisten” (trebles), and one “organista” in the “Capellen oder Cannthorey” (chapel or cantorey); among the other ranks, only one “geyger” (string instrument player) is listed.[2] This discrepancy is explained by the different functions of the musicians: The singers were needed for worship services, while the trumpeters and drummers primarily served as a visual and acoustic heraldic sign and were considered the much-cited “Ehr und Zier” (honour and ornament), an indispensable status symbol of the ruler.[3] The other musicians, however, primarily served the so-called “Kurzweil” (diversion) and were only indirectly representative, for example at imperial diets or as musical ambassadors, when they performed, dressed in the ruler’s livery, in imperial cities and at princely courts, for example as “zwayen siner Maiestat Luttenschlager” (two of His Majesty’s lutenists), receiving substantial monetary gifts for their performances.[4] Venetian envoys who met Maximilian in Strasbourg in 1492 reported the honour they received through the visit of the royal musicians to their quarters: fourteen trumpeters with large drums appeared, as well as pipers, drummers, and lutenists. Additionally, three brothers with their father, who played a claviorganum (a keyboard instrument that combines organ and harpsichord), lute, and fiddle.[5] This artistic family enterprise is also explicitly described as belonging to the court, although they have not yet been documented archivally.

The representative function—more so than his own musical needs—primarily explains Maximilian’s interest in associating outstanding instrumental musicians with his court. It is well known that music and musicians at a court were considered an important part of the ruler’s glory.[6] In this sense, reports of Maximilian’s special love for music can be understood as part of a ruler’s praise, as can be read in the biography of his humanistically trained personal physician Johannes Cuspinianus:

“Musices vero singularis amator, quod vel hinc maxime patet, quod nostra aetate musicorum principes omnes in omni genere musices omnibusque instrumentis in ejus curia veluti in fertilissimo agro succreverint, veluti fungi unâ pluviâ nascuntur”[7]

(He was a unique lover of music, which is especially evident from the fact that all the great masters of music in our time in every genre and on all instruments flourished at his court, as if on the most fertile soil, just like mushrooms that shoot up after a single rain-shower.)

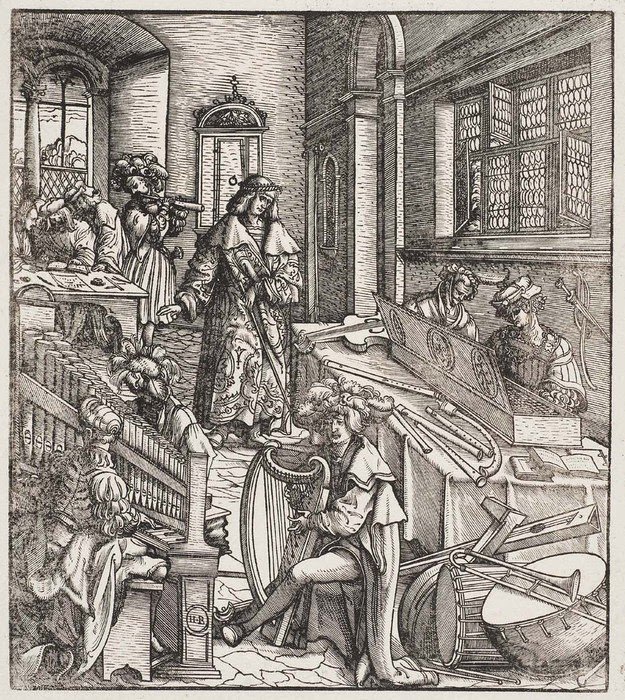

The often-cited passage in the epic poem Weißkunig (The White [or Wise] King), an ambitious publication project comparable to the Triumphzug, is to be understood in a similar way. Here, it is reported how the young king, an idealised alter ego of Maximilian, establishes a “Canterey” (chapel), “mit ainem sölichen lieblichn gesang, von der menschen stymm wunderlich zu hören, vnd söliche liebliche herpfen, von Newen wercken, vnd mit suessem saydtenspil, das Er alle kunig übertraff, vnd Ime nyemandts geleichen mocht, sölichs unnderhielt Er, fur vnd fur, das ainem grossen furstenhof geleichet, […]” (with such sweet singing, wonderful to hear from human voices, and such lovely harps, new instruments, and sweet string music, that he surpassed all kings, and none could compare to him. Such music he maintained continuously, as befits a great princely court).[8] In the accompanying illustration, the Weißkunig can be seen amidst instrumental musicians, literally giving them the “beat” with a long staff (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33).[9] Interpreted differently, the illustration shows that all music at the court traces back to and references its actual centre, the ruler.

[1] For information on the Triumphzug, its different versions, and its complex history, see Appuhn 1979 and Michel/Sternath 2012; on its significance for Maximilian, see Müller 1982; on the relationship between depiction and reality, see Polk 1992; The quotation comes from the earliest surviving formulation of the iconographic program of the Triumphzug in 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (quotation from the Augsburg Baumeisterbücher of 1491, the council’s account books for income and expenses).

[5] See Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] See Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Quoted in Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] See Schwindt 2012.

[1] For information on the Triumphzug, its different versions, and its complex history, see Appuhn 1979 and Michel/Sternath 2012; on its significance for Maximilian, see Müller 1982; on the relationship between depiction and reality, see Polk 1992; The quotation comes from the earliest surviving formulation of the iconographic program of the Triumphzug in 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (quotation from the Augsburg Baumeisterbücher of 1491, the council’s account books for income and expenses).

[5] See Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] See Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Quoted in Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] See Schwindt 2012.

[10] She received 50 guilders “zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung” (for her maintenance and living) in June 1520 when the court chapel was dissolved after Maximilian’s death; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Such as “Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher”, who were expressly paid for their services “bei Tanz” at the 1491 carnival; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] For a compilation of music-related illustrations, see Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] See Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[16] Polk 1992, 86 (with references from Augsburg archives).

[17] See Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] See Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (including the following).

[20] According to payments in the Augsburg (D-As) Baumeisterbuch 103 (1509), fol. 24v, and 104 (1510), fol. 28; kindly communicated by Keith Polk.

[21] See Jahn 1925, 10 ff., and Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] See Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] See the letter from Paul Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadian on May 14, 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So the wording in the formulation of the iconographic program in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] See Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, title page of the tenor partbook; for dating, see Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] See Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] See Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[36] Senn 1954, 26, referring to Maximilian’s letter in A-Wn, Cod. 10100b, fol. 15r–v, edited in Kraus 1875, 39. I owe the correction in this context to Grantley McDonald, who also drew my attention to the ‘Lauerpfeif’ (KHM Vienna, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, A 74), a cannon with two pipes attached to the side of the gun barrel that can be used to produce whistling sounds; see Krammer 2025.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; facsimile and description in Kirnbauer 2003. For lute tablatures of the next generation from the southern German-speaking area, see » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] See Moser 1966, 26 and 182, footnote 35.

[40] See Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; see also » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Recommended Citation:

Martin Kirnbauer: „Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).