“Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen krumphörner”: Shawms, trombones und crumhorns

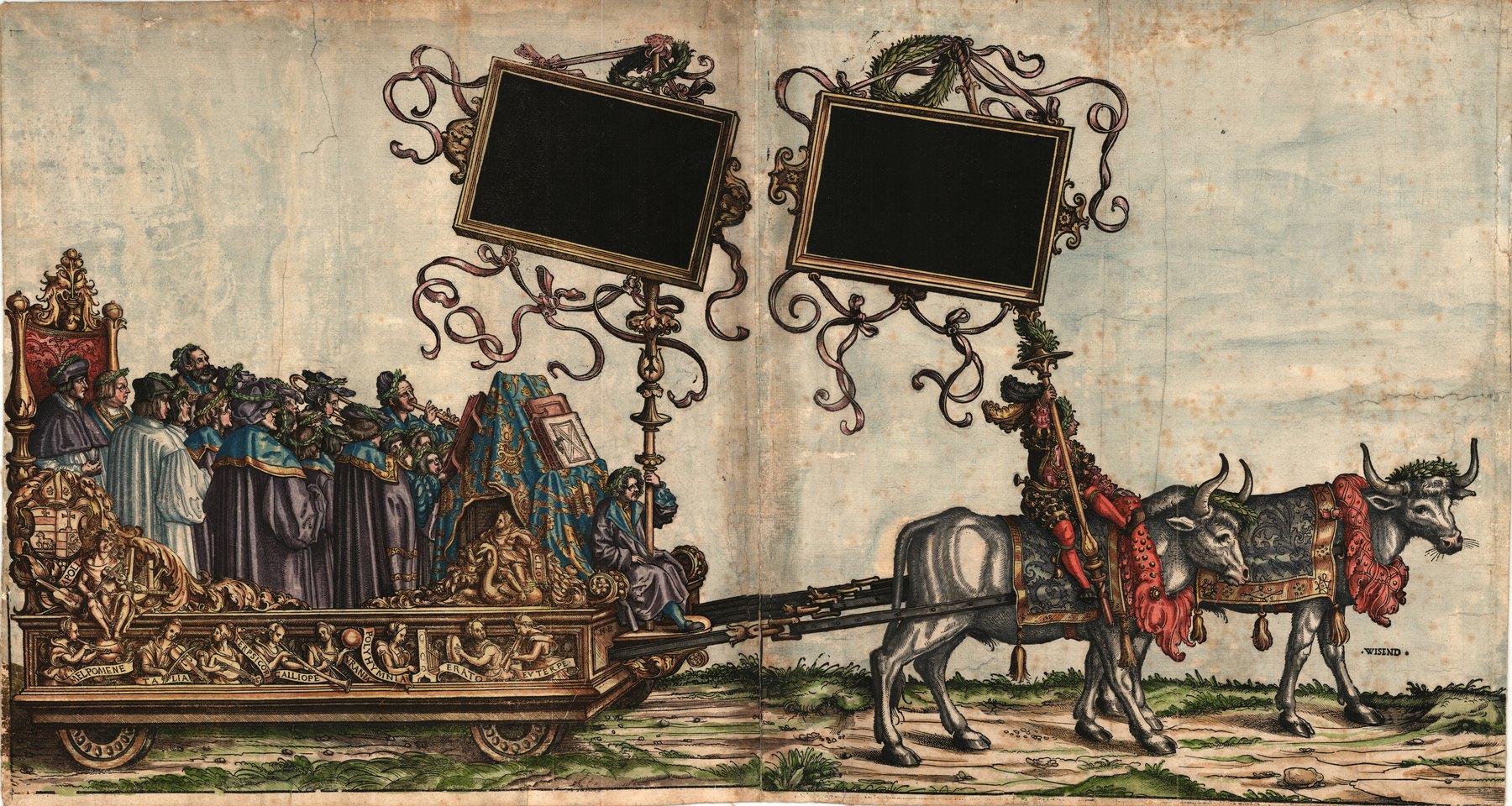

Hans Neuschel (c. 1470–1533) is named as the “Maister” of the second musicians carriage in the Triumphzug, “Musica, Schalmeyen, pusaunen, krumphörner” (Music: shawms, trombones und crumhorns) (» Abb. Triumphzug Bläser). He was never a permanent member of Maximilian’s court chapel, but worked as a trumpet maker and city piper in Nuremberg.[21] Although Maximilian evidently valued him and often requested him from the Nuremberg council as a musician, Neuschel himself was not entirely happy about this honour, as the travels to Maximilian, which sometimes occupied him “lenger dann jar und tag” (longer than a year and a day), caused him to neglect his other customers: “das ihm dadurch sein werkstat ganz erniderlegt und er in seinem abwesen von seinem handwerk feiern, dadurch seine kunden und kaufleut verlieren und des, so er mit solchem seinem handel verdienen und erarbeiten mog, empern und allein vil schulden, darein er hievor, als er kais. maj. ein zeitlang nachgeraist sei, muss gewarten” (because his workshop was completely idle and he had to abstain from his craft in his absence, thereby losing his customers and traders, and forgoing the income he would otherwise earn, and expecting only debts because he had to follow the emperor).[22] Trombonists like Neuschel, or Hans Stewdl (or Steydlin), who is mentioned elsewhere in the Triumphzug, were specialists who performed with the singers on special occasions. For example, it is noted that during the Imperial Diet in Trier in 1512, the emperor had “Misse gehoret, die ist discantirt. Darinn mitl zincken vnd basunen geblasen” (heard Mass, which was sung in discant [polyphony]. Therein, cornets and trombones played).[23] This suggests that one or more trombones played the lower parts of a vocally performed polyphonic Mass while a cornet player played the upper part and presumably improvised. It is also conceivable that a trombonist played a new or additional contratenor part. (A possible impression of such a “loud” ensemble is provided by » Hörbsp. ♫ La la hö hö.)

This exact situation is depicted in the Triumphzug on the carriage of the “Musica Canterey” (Music: chapel) (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei) where alongside the singers, a cornet player and a trombonist can be seen. According to the pictorial programme, Augustin Schubinger and Hans Stewdl are depicted here. Schubinger (» G. Augustin Schubinger ) was evidently the specialist for cornet playing in his time (»H. Zink / Cornett). He came from an Augsburg city piper family that produced many outstanding wind players.[24] Augustin was probably born around 1460 and is documented as a city piper in Augsburg from 1477. Temporarily also in the service of the Margrave of Brandenburg and Maximilian’s father, Frederick III, he can be traced between 1489 and 1493 in northern Italy and especially in Florence, where Henricus Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) also worked. After the fall of the Medici, Augustin returned to Habsburg service; again, in a certain parallel to Isaac, who returned to Maximilian’s court a few years later. Schubinger seems to have gradually specialized in the cornet, as at the beginning of his career he is still referred to as a “pfeifer,” generally understood to be a professional musician and player of wind instruments, then as a “busauner” (trombonist), indicating a certain specialisation in contratenor parts, and also as a lutenist. This shows that instrumental musicians were generally proficient in several instruments. In the employment contract of Augustin’s younger brother Ulrich with the Archbishop of Salzburg in 1519, it is stated that he serves his new lord “mit ribeben, geygen, pusawn, pfeiffen, lawtten und annders instrumentn in der musiken, darauf er etwas khann” (with viols, fiddles, trombones, pipes, lutes, and other instruments in music, on which he can play).[25] With the exception of keyboard instruments, all conceivable wind, plucked, and string instruments are listed here, which were quite evidently mastered and probably played.

[21] See Jahn 1925, 10 ff., and Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] See Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[1] For information on the Triumphzug, its different versions, and its complex history, see Appuhn 1979 and Michel/Sternath 2012; on its significance for Maximilian, see Müller 1982; on the relationship between depiction and reality, see Polk 1992; The quotation comes from the earliest surviving formulation of the iconographic program of the Triumphzug in 1512 in » A-Wn Cod. 2835, fol. 3v.

[2] Koczirz 1930/31, 531 f.

[4] Nedden 1932/33, 27 (quotation from the Augsburg Baumeisterbücher of 1491, the council’s account books for income and expenses).

[5] See Simonsfeld 1895, 267 f.

[6] See Strohm 2009, 98.

[7] Quoted in Waldner 1897/98, 2.

[8] Treitzsaurwein 1775, 78.

[9] See Schwindt 2012.

[10] She received 50 guilders “zu Irer vnderhaltung vnd Zerung” (for her maintenance and living) in June 1520 when the court chapel was dissolved after Maximilian’s death; Koczirz 1930/31, 535.

[11] Such as “Hannsen pfeiffer vnnd matheusen Trumelschlacher”, who were expressly paid for their services “bei Tanz” at the 1491 carnival; Waldner, 1897/98, 52.

[12] Appuhn 1979, 172 f.

[13] For a compilation of music-related illustrations, see Henning 1987, 69–94

[15] See Gombosi 1932/33; Heinzer 1999, 92 ff.

[16] Polk 1992, 86 (with references from Augsburg archives).

[17] See Kirnbauer 2005.

[18] See Kirnbauer 2003, 243–248 (including the following).

[20] According to payments in the Augsburg (D-As) Baumeisterbuch 103 (1509), fol. 24v, and 104 (1510), fol. 28; kindly communicated by Keith Polk.

[21] See Jahn 1925, 10 ff., and Kirnbauer 2000, 25 ff.

[22] Kirnbauer 1992, 131.

[23] Nedden 1932/33, 31.

[24] See Polk 1989a; Polk 1989b.

[25] Hintermaier 1993, 38.

[26] See the letter from Paul Hofhaimer to Joachim Vadian on May 14, 1524; Moser 1966, 56.

[29] Nowak 1932, 84.

[30] Praetorius 1619, 148.

[31] So the wording in the formulation of the iconographic program in » A-Wn Ms. 2835, fol. 8v.

[32] See Welker 1992, 189–194.

[33] Aich 1515, title page of the tenor partbook; for dating, see Schwindt 2008, 117 ff.

[34] See Bernoulli/Moser 1930, v–vii; McDonald/Raninen 2018.

[35] See Brinzing 1998, 137–154; Filocamo 2009.

[36] Senn 1954, 26, referring to Maximilian’s letter in A-Wn, Cod. 10100b, fol. 15r–v, edited in Kraus 1875, 39. I owe the correction in this context to Grantley McDonald, who also drew my attention to the ‘Lauerpfeif’ (KHM Vienna, Hofjagd- und Rüstkammer, A 74), a cannon with two pipes attached to the side of the gun barrel that can be used to produce whistling sounds; see Krammer 2025.

[37] » A-Wn, Mus. Hs. 41950; facsimile and description in Kirnbauer 2003. For lute tablatures of the next generation from the southern German-speaking area, see » H. Lautenisten und Lautenspiel (Kateryna Schöning).

[38] Gerle 1533, fol. IIv.

[39] See Moser 1966, 26 and 182, footnote 35.

[40] See Moser 1966, 137–140; Radulescu 1978, 66 f.; see also » C. Orgeln und Orgelmusik.

Recommended Citation:

Martin Kirnbauer: “Instrumentalkünstler am Hof Maximilians I.”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/instrumentalkunstler-am-hof-maximilians-i> (2016).