Hermann Edlerawer and the building of the Cantorey

Hermann Edlerawer from the Diocese of Mainz (» G. Hermann Edlerawer) came to Vienna by 1413/1414 at the latest, when he enrolled at the university. From the 1420s onwards, he served King Sigismund, and thereafter, until at least 29 April 1437, Duke Albrecht V. On 27 January 1436, he sealed a document as “official and land clerk of the Schottenkloster”.[77] Between 1440 and 1444, he is attested as school cantor of St Stephen’s (although he may have held the office as early as 1438 and until around 1449; evidence for this is lacking). His career was untypical for a church musician of the time. He first appears in the Vienna city accounts in 1438, when the council paid “dem hermanne” 10 tl.[78] Since no school cantor had previously received such a high salary from the city council, this may have concerned a special civic event (cf. Ch. Musical services of the Cantorey from c. 1440) or a reimbursement of expenses. In 1440, “hermanne cantori” was explicitly reimbursed 20 tl. for “building assistance for his Cantorey”, and in 1441 a further 12 tl.[79]

Until around 1440, music instruction by the school cantor in all likelihood took place primarily in the school. Elsewhere in Europe, rood lofts were indeed used for musical performances and often housed a small organ, but at St Stephen’s, the space on the lettner was significantly obstructed by other Masses and ongoing construction work.[80] Liturgical singing had to take place at the prescribed locations—also in the high choir—while no endowments involving the Cantorey are currently known for the altars on the lettner.

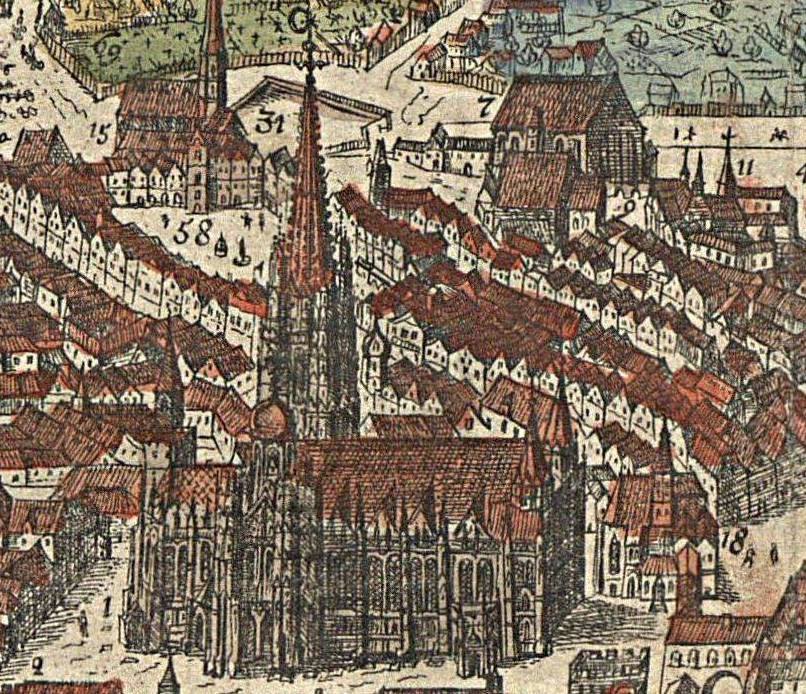

The Kantoreihaus—as the cantor’s residence and workplace—is mentioned for the first time in a document from 1438.[81] It was not a freestanding building, but was attached to the side of the Magdalene Chapel in the St Stephen’s cemetery (» Fig. Cantorey and Magdalene Chapel). The Magdalene Chapel formed the upper storey of the New Charnel House, which had been erected in 1304 above the old Virgil or Erasmus Chapel at the corner of the St Stephen’s cemetery. The chapel belonged to the Viennese Schreiberzeche, that is, the brotherhood of the city’s clerical officials (» E. Städtisches Musikleben; » E. Ch. Musikergenossenschaften).

That Hermann Edlerawer personally oversaw the construction or continuation of the Cantorey is evident, among other things, from a municipal legal dispute dated 5 November 1440: as already noted in the aforementioned document from 1438, the Cantorey building bordered the cemetery wall, on the other side of which stood the house of the apothecary Nicolas Laynbacher. Laynbacher sued the cantor over rainwater running off the tiled roof of the Cantorey onto his property. The ruling was in Edlerawer’s favour, as the Cantorey roof did not extend beyond the cemetery wall, and the wall itself was the property of the church.[82]

Previously, the Cantorey had no building of its own outside the church; singing was practised either in the school or in the church itself, which was disruptive alongside other activities. From now on, suitable pupils could be prepared for singing duties in a building specifically designated for that purpose. This advantage was confirmed by the 1446 ordinance for the civic school issued by the city council (» E. Städtisches Musikleben): it permitted the cantor to take suitable pupils out of the school for singing (but only before lunch), and not always all together for every singing duty, but rather different groups as needed. In return, it withdrew from him and his subcantor the classroom (“locatei”) in the school where the singing pupils had previously been taught together, regardless of their level of training (“irer begrifflichait”), which had led to “confusion in the choir”. Since the cantor and subcantor (assistant to the school cantor; cf. Ch. Personnel requirements for church music) were not only responsible for teaching music, one of them was to remain at the school for the other lessons after lunch. The final recommendation is important: if the arrangement did not suit him, the cantor could keep the boys at his house.[83]

“Item furbaser sol der kantor kain sundere locacein in der schul haben, als es auch vor jarnn gewesen ist. Wann er und ein subcantor von irrung des kors dieselben nicht wol verpesen mugen, sunder all schuler, die der cantor hat, sol man seczen nach gelegenhait irer begrifflichait, und wenn er sein schuler zu dem kor nuzen wil, so mag er sew vodern. Auch mugen im die locatenn ander knaben zuschickchenn, die fugsam sein zu dem kor, doch also das ein austailung werde der knaben, also das sy nicht all zu allen ambten geen, sunder yetz ain tail, darnach einn ander tail zu einem andern ambt. Darumb sol der cantor und sein subcantor gehorsam tun, und sullen vor essens alain dem kor wartenn. Aber nach essens sol ir ainer stetlich in der schul beleiben und den obristen locaten helffen zu lernen die schuler. Wer aber, das die vorgeschrieben weis von dem cantor nicht fugsam dewcht sein, so halt der cantor sein knaben in seinem haws fur sich selber.”

(Furthermore, the cantor shall not have a separate classroom in the school, as was the case in previous years. For he and a subcantor cannot properly improve the confusion in the choir, but rather all pupils under the cantor shall be placed according to their comprehension. And when he wishes to use his pupils for the choir, he may request them. By the classroom teachers he may also be sent other boys who are suitable for the choir, but in such a way that there is a distribution of the boys, so that they do not all serve in all services, but now one group, then another group for a different service. Therefore, the cantor and his subcantor shall obey, and shall attend to the choir only before the meal. But after the meal, one of them shall remain regularly in the school and assist the senior teachers in instructing the pupils. However, if the aforementioned arrangement does not seem suitable to the cantor, he may keep the boys at his house for himself.)[84]

Thus, not only was a suitable rehearsal space for music created, but also a structural demonstration of the importance of church singing through the Cantorey, and at the same time of Hermann Edlerawer’s significance as cantor. There is scarcely any evidence elsewhere in contemporary Europe for dedicated Cantorey buildings. Yet it is no coincidence that at the Schottenkloster, where Edlerawer had served as administrator in 1436, a “singing room” (Singstube) was built between 1446 and 1449 under Abbot Martin von Leibitz (1446–1461).[85]

[77] Melk, Abbey Archive, Charters (1075–1912), no. 1436 I 27, http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-StiAM/archive [02.06.2016].

[78] OKAR 5 (1438), fol. 92r.

[79] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 98r, and OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 111r.

[80] The latter note is based on kind information from Prof. Barbara Schedl, Vienna.

[81] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2656 (3 July 1438). Other, partly contradictory, details cited in Ebenbauer 2005, 38 f.

[82] A-Wda, Charter 14401105.

[83] See also Flotzinger 2014, 56 f.

[84] Boyer 2008, 36 f.

[85] Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1. On Martin von Leibitz and his Caeremoniale (A-Wn Cod. 4970), see Schusser 1986, 82, no. 65, and » A. Melk Reform.

[1] Perger/Brauneis 1977; Schusser 1986, 17–41.

[2] Zschokke 1895, 2.

[3] Mantuani 1907, 209–210. Flotzinger 1995, 89–90. For general information on organs, see » C. Organs and Organ Music.

[4] Mantuani 1907, 209–210, suspects that the term “organist” refers to an organ builder, who was, however, referred to as “organ master” (e.g. “Petrein the organ master 15 tl” in the city accounts of 1380, » A-Wn Cod. 14234, fol. 39r). This designation is to be understood as a Germanisation of the term magister organorum.

[5] Incorrectly assumed for 1334 by Flotzinger 1995, 90. On the school cantor Peter Hofmaister, see Ch. Development of the Choir School of St Stephen’s.

[6] This and the following information on organs at St Michael’s according to Perger 1988, 91, and the churchwarden accounts in the College Archive of St Michael’s.

[7] On Hans Kaschauer and his father Jakob Kaschauer, who painted the large panel of the high altar between 1445 and 1448, see Perger 1988, 84.

[8] Schütz 1980, 14.

[9] Mayer 1880; Schusser 1986, 66, no. 31/1 (Richard Perger). The university confirmed this regulation on 14 April 1411: see Uiblein, Acta Facultatis 1385–1416, 355.

[11] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 15; Czernin 2011, 59.

[12] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 25.

[13] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 29.

[14] See Lind 1860, 11; Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1; Perger/Brauneis 1977, 275.

[15] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1.

[16] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 1935.

[17] Vienna City and State Archive, Charter 1935, 21 November 1412; see also Schusser 1986, 139, no. 115.

[18] Boyer 2008, 25.

[19] An attempt to distinguish between chapter cantor (“Sangherr”) and school cantor is made by Mantuani 1907, 287 f.

[20] Zschokke 1895, 25–48; Flieder 1968.

[21] Grass 1967, especially 464–467.

[22] Flieder 1968, 140–148, especially 148.

[23] Edited by Ogesser 1779, Appendices X and XI, 77–83. See also Flieder 1968, 155, 158–160.

[24] A statute from 1367 stipulated that the roles of “choirmaster” (magister chori) and dean should be united in one person (Göhler 1932/2015, 141 f.), which, however, apparently did not occur (Flieder 1968, 173 f.).

[25] Mantuani’s (Mantuani 1907, 288) mistaken equation of “choirmaster” with “cantor” has often been repeated. The German term for the latter was “Sangherr”. Ulreich senior (1365?) was “magister chori et cantor” (Göhler 1932/2015, 142 and fig. 11), i.e. the two titles were not synonymous. On the correct use of the terms, see Ebenbauer 2005, 14 f. (choirmaster responsible for the parish), although Mantuani is cited there without contradiction.

[26] On the location of altars and chapels, see Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61–63. I am sincerely grateful to Prof. Barbara Schedl for her advice in this regard.

[27] Ogesser 1779, 80–82. See the list of procession participants from a Liber ordinarius of St Stephen’s (» A-Wn Cod. 4712): » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[28] Zschokke 1895, 30–46; Flieder 1968, 254–266.

[29] Zschokke 1895, 33.

[30] In ecclesiastical service regulations, the Latin equivalent “alta voce” was traditionally used.

[31] Zschokke 1895, 37.

[32] Zschokke 1895, 40.

[33] Zschokke 1895, 84–91.

[34] Raimundus Duellius, Miscellanea, Augsburg/Graz 1724, Vol. II, 78 and 82.

[35] “Ne quis eciam nimium voces agitare aut in altum audeat elevare habeatque et cantum Bassum et nimis clamorosum ad medium reducere.” (Zschokke 1985, 89 f.) See also Rumbold/Wright 2009, 44.

[36] Archdiocesan Diocesan Archive Vienna (A-Wda), Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 107r.

[37] Grass 1967, 482–487.

[38] On 12 March 1421, over 200 Viennese Jews were burned in Erdberg by order of Duke Albrecht V, as reported, among others, by theology professor Thomas Ebendorfer (Lhotsky 1967, 370 f.).

[39] Zapke 2015, 87 f.

[40] Gall 1970, 85–86; Flotzinger 2014, 44–47, 54 f.

[41] Gall 1970, 34, 86 f.; Zapke 2015, 88 f.

[42] Pietzsch 1971, 27 f.

[43] Mantuani 1907, 283 and note 1; Enne 2015, 379 f.

[44] See Strohm, Ritual, 2014 on the temporal awareness of ecclesiastical regulations.

[45] “Canons” here refers to the “octonarii”, the priests of the collegiate chapter entrusted with pastoral care.

[46] A-Wda, Charter 13391028; see Currency: 1 pound (tl.) = 8 large (“long”) shillings (s.) = 240 pfennigs (d., denarii).

[47] Camesina 1874, 11, no. 36. The distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor is convincingly demonstrated in Göhler 1932/2015, 228 f.

[48] A-Wda, Charter 14200525; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/14200525/charter [02.06.2016].

[49] Camesina 1874, 21, no. 94.

[50] Camesina 1874, 21–23, no. 96.

[51] Accounts of the churchwarden’s office of St Stephen’s (in the Vienna City and State Archive), see Uhlirz 1902. Extracts from the account books of St Michael’s in Schütz 1980.

[52] Schütz 1980, 124. Schütz 1980, 15, mistakenly equates the schoolmaster with one of the two cantors.

[53] See Uhlirz 1902, 251 and elsewhere. Knapp 2004, 268, interprets this as a Marienklage (Lament of Mary), which is less likely from a liturgical perspective.

[54] Uhlirz 1902, 364, 384. The Easter sepulchre was an artistically crafted sculpture.

[55] On the locations of the organs, see also Ebenbauer 2005, 40 f.

[56] Uhlirz 1902, 337 (1417).

[57] For example, 1415: Uhlirz 1902, 299.

[58] Uhlirz 1902, 267 (1407).

[59] Vienna City and State Archive, 1.1.1. B 1/ Main Treasury Accounts, Series 1 (1424) etc.: hereafter abbreviated as OKAR 1 (1424) etc. (» A-Wsa OKAR 1-55).

[61] For detailed information on » A-Wn Cod. 4712 see Klugseder 2013; see also » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession. The liturgy of the St Stephen’s chapter is represented by the “Turs Missal” (c. 1430, produced under Provost Wilhelm von Turs), which still belongs to the Archiepiscopal Chapter and is of particular interest for art history.

[62] A-Gu Cod. 756, fol. 185r; see » A. Weihnachtsgesänge.

[63] The former is the earliest dated addition, indicating that the codex must have been created before 1404.

[64] However, the Sunday Vocem iucunditatis was dedicated to St Koloman (» A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r).

[65] For polyphonic conclusions to monophonic plainsongs, as seems intended here, there is evidence from the fourteenth century in France and Italy.

[66] The procession descriptions in the original corpus of » A-Wn Cod. 4712, a Liber ordinarius of the Diocese of Passau, replicate word-for-word the regulations for Passau itself (courtesy of Robert Klugseder), but are also applicable to Vienna due to the similar ecclesiastical topography of both cities. Added marginal notes clarify the route descriptions with direct reference to Vienna: Klugseder 2013 devotes a separate chapter to the Vienna-related marginalia in Cod. 4712. (See also the digital edition of the Passau Liber ordinarius, http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.passau). The Corpus Christi procession is represented in Cod. 4712 only by a brief marginal note on fol. 67v. However, the list of participants appears in the appendix (fol. 109r), edited in » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[67] Camesina 1874, 24, no. 101.

[68] Camesina 1874, 26, nos. 113 and 114 (12 and 13 December 1404).

[69] Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50 (Lohrmann).

[70] The claim that the Dorothea Altar stood in front of the rood screen (Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61 and note 214) cannot be derived from the records of 1403–1404. The altar’s income belonged “to the school corporation”, which in this context did not refer to a “brotherhood of pupils” (Lohrmann in Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50), but to the school building itself.

[71] Not to be confused with a canon of the same name, Peter of St Margrethen, active in 1399.

[72] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, nos. 2159 and 3076. 1449: OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 28v.

[73] Some of the information in Brunner 1948 is outdated.

[74] Göhler 1932/2015, 228, no. 98.

[75] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2978; a mention of “Peter Marold, cantor” in OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 19v, may refer to another cantor of the same name or be retrospective.

[76] All except Neuburg are listed in Czernin 2011, 87 f. This list also includes the chapter cantors Ulreich Musterer (†1426), Wolfgang von Knüttelfeld (†1473), Hanns Huber (1474), Brictius (1470s), and Conrad Lindenfels (1479–1488, previously school cantor 1449–1457); a “Kaspar” (1448) may be identical with choirmaster Kaspar Wildhaber (1423/24). The additional names in Flotzinger 2014, 57, note 49, all refer to “choirmasters”, whom Flotzinger, following Mantuani 1907 and Flieder 1968 mistakenly equates with cantors. See Ch. The institutional foundation of the St Stephen’s chapter.

[77] Melk, Abbey Archive, Charters (1075–1912), no. 1436 I 27, http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-StiAM/archive [02.06.2016].

[78] OKAR 5 (1438), fol. 92r.

[79] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 98r, and OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 111r.

[80] The latter note is based on kind information from Prof. Barbara Schedl, Vienna.

[81] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2656 (3 July 1438). Other, partly contradictory, details cited in Ebenbauer 2005, 38 f.

[82] A-Wda, Charter 14401105.

[83] See also Flotzinger 2014, 56 f.

[84] Boyer 2008, 36 f.

[85] Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1. On Martin von Leibitz and his Caeremoniale (A-Wn Cod. 4970), see Schusser 1986, 82, no. 65, and » A. Melk Reform.

[86] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 97v. The cantor received 60 d.

[87] For example, OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 112v (five weeks; from November before St Martin’s Day to St Lucy’s Day, 13 December).

[88] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 139v. In addition, 24 “peace masses” were sung daily until the Friday after Laetare (4th Sunday in Lent), for which “Hermann and the boys were paid 32 d. for each mass sung”.

[89] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 140r. The cantor received 21 d. for each “votive”. The dean, levites (probably choirboys), sacristan, and organist are also mentioned.

[90] For example, OKAR 9 (1445). The (unnamed) cantor received 3 s. (= 90 d.).

[91] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 3, no. 3848; Camesina 1874, 92–93, no. 437.

[92] OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 37r.

[93] As often stated in older literature, e.g. Strohm 1993, 507. Corrected in Rumbold/Wright 2009, 47.

[94] Camesina 1874, 78–80, no. 364 (1445, undated).

[95] See Weißensteiner 1993.

[96] OKAR 9 (1445), fol. 51r; the city accounts for 1446–1448 are lost. See Rumbold/Wright 2009, 48–50.

[97] OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 32r.

[98] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 3333 (for 1449); OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 41r.

[99] Zschokke 1895, 375; Rumbold/Wright 2009, 50–51. Lindenfels quickly became unpopular after his installation in 1479 by claiming, as chapter cantor, the right to choose his canon’s residence ahead of more senior canons (A-Wda, Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 18r).

[100] OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 82v. The total cost for the carpenter and locksmith (for iron bars to secure the choir books) amounted to 160 d.

[101] OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 118v. The total cost for the carpenter and painter amounted to 95 d.

[102] OKAR 16 (1458); OKAR 36 (1474), fol. 22r.

[103] OKAR 42 (1478), fol. 32v.

[104] Text provided, among others, in Mantuani 1907, 285–287; see also Gruber 1995, 199; Flotzinger 2014, 58 f.

[105] See Strohm 2014.

[106] Uhlirz 1902, 477.

[108] A-Wda, Charter 15060119; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/15060119/charter [02.06.2016].

Recommended Citation:

Reinhard Strohm: “Musik im Gottesdienst. Wien ”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musik-im-gottesdienst-wien-st-stephan> (2016).