Tropes and other marginal phenomena in the Ordo of St Stephen’s

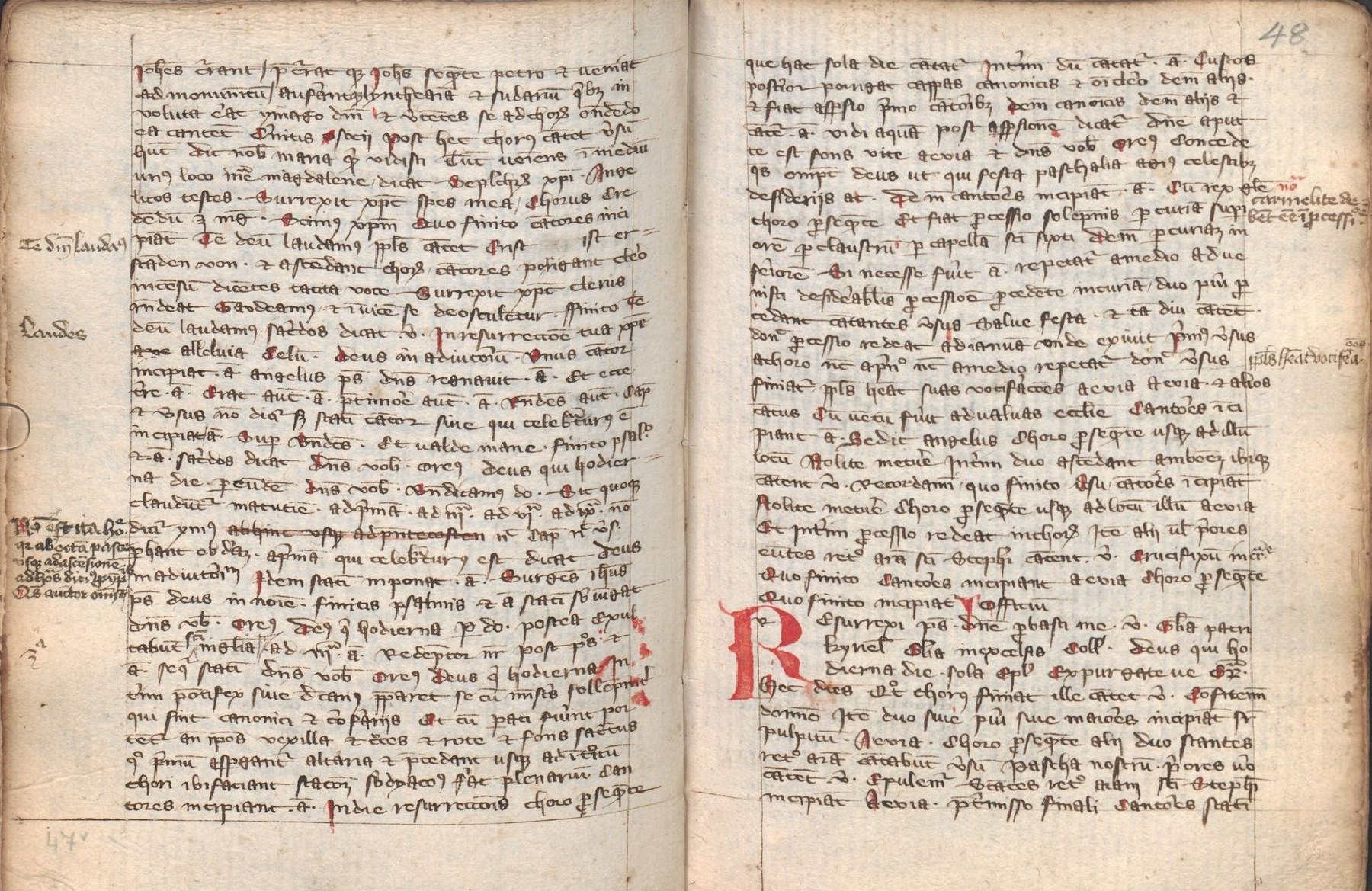

The compact volume » A-Wn Cod. 4712 of the Austrian National Library is labelled “ordo sive breviarium” (order or abbreviation). In it, the liturgical rite of St Stephen’s is described—much abbreviated, as is typical in such a Liber ordinarius—using incipits and rubrics instead of full texts.[61] Only the services of the chapter are listed, not those of the parish or the many privately endowed altars and chapels. The main text, written around 1400 (fols. 1–107), essentially conveys the Passau diocesan liturgy, which was used in the parishes of Vienna. Numerous marginal notes from the following decades explain the further development of the rite and its specific practice in Vienna. For example, a marginal note (fol. 9v) for the feast of St Stephen (26 December) states that (on the eve) no Compline is sung, but instead “a sermon is given to the clergy and the people” (fit sermo ad clerum et ad populum). For the Introit of the Mass on St Stephen’s Day itself, the main text prescribes unspecified tropes, possibly including the Introit trope De Stephani roseo sanguine martirii vernant primicie (From Stephen’s rose-red blood bloom the first fruits of martyrdom), which is recorded in the Seckau Cantionarius of 1345 (» A-Gu Cod. 756).[62] There are also Mass tropes for the Feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December), Epiphany (6 January), and other feasts of the year; none of these are preserved in the printed » Graduale Pataviense of 1511.

The organ is frequently mentioned in the service order of A-Wn Cod. 4712, especially in connection with the Marian Masses (e.g. fol. 28v). The main location of the small organ may have been at the Altar of Our Lady in the (northern) Marian choir.

A longer addendum on fol. 35v informs that, in accordance with a decree issued by the Bishop of Passau, Georg von Hachloch (Hohenlohe), on 12 November 1404, the entire Divine Office (Officium diurnum et nocturnum) is to be solemnly celebrated once a week with nine readings in honour of St Stephen, the diocesan patron of Passau. A second hand adds that this decree was solemnly read from the pulpit in the Chapter of St Stephen in Vienna on 1 June 1411.[63]

Specifically concerning Viennese customs, a note (fol. 50r) explains that on the octave of Easter, the rite of dedication of St Stephen is sung, whereby the Sunday after Easter (Quasimodogeniti) effectively became a second church consecration festival. On this Sunday, the “Heiltum”, the collection of all relics belonging to the church, was also shown to the people, from 1483 onwards on the specially constructed “Heiltumsstuhl” in front of the church (» Fig. Viennese Heiltumsstuhl; » F. Lokalheilige). On the preceding Saturday, the consecration festival of the Tirna Chapel (addendum on fol. 50r) was celebrated.

That vernacular songs were also part of the Easter celebration in Vienna (» A. Osterfeier) is evidenced by mentions of “cries of the people” in the main text (» Fig. Vociferationes populi). Further cries of the people were intended for the litany of the Rogation procession (cf. Ch. Processions of St Stephen’s).

Highly interesting is an isolated mention of polyphonic singing in the main text (fol. 54r), which is also found in other copies of the Passau Liber ordinarius and thus applied throughout the entire diocese (kindly communicated by Robert Klugseder). In the Mass of the fifth Sunday after Easter (Vocem iucunditatis), the sequence Laudes salvatori was sung, “which should be pleasantly concluded with discant” (que iocunde cum discantu finiatur). This refers to Notker’s prose Laudes salvatori for Easter Sunday, which was only fully replaced by Victime paschali laudes following the Council of Trent in the sixteenth century. In the second volume of his Choralis Constantinus (» G. Henricus Isaac), Isaac composed an Easter sequence in which Laudes salvatori (beginning with the second verse, Et devotis melodiis), Victime paschali, and even the antiphon Regina celi letare are combined. One must ask why such musical embellishment was prescribed for a comparatively unimportant Sunday[64], when it would have suited other feasts, such as Easter, at least equally well. Laudes salvatori was also sung on Easter Sunday (fol. 48v). Did the ordo here make something obligatory that could be done ad libitum on other days? It is proposed that this particular polyphonic contribution, probably performed by the priests (as cantor, schoolmaster or pupils are not mentioned), may have stemmed from an already long-established Passau foundation and was regarded as especially venerable. The type of discantus referred to here may have corresponded to that form of polyphony for which there is abundant evidence from monasteries in the region (» A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit).[65]

[61] For detailed information on » A-Wn Cod. 4712 see Klugseder 2013; see also » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession. The liturgy of the St Stephen’s chapter is represented by the “Turs Missal” (c. 1430, produced under Provost Wilhelm von Turs), which still belongs to the Archiepiscopal Chapter and is of particular interest for art history.

[62] A-Gu Cod. 756, fol. 185r; see » A. Weihnachtsgesänge.

[63] The former is the earliest dated addition, indicating that the codex must have been created before 1404.

[64] However, the Sunday Vocem iucunditatis was dedicated to St Koloman (» A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r).

[65] For polyphonic conclusions to monophonic plainsongs, as seems intended here, there is evidence from the fourteenth century in France and Italy.

[1] Perger/Brauneis 1977; Schusser 1986, 17–41.

[2] Zschokke 1895, 2.

[3] Mantuani 1907, 209–210. Flotzinger 1995, 89–90. For general information on organs, see » C. Organs and Organ Music.

[4] Mantuani 1907, 209–210, suspects that the term “organist” refers to an organ builder, who was, however, referred to as “organ master” (e.g. “Petrein the organ master 15 tl” in the city accounts of 1380, » A-Wn Cod. 14234, fol. 39r). This designation is to be understood as a Germanisation of the term magister organorum.

[5] Incorrectly assumed for 1334 by Flotzinger 1995, 90. On the school cantor Peter Hofmaister, see Ch. Development of the Choir School of St Stephen’s.

[6] This and the following information on organs at St Michael’s according to Perger 1988, 91, and the churchwarden accounts in the College Archive of St Michael’s.

[7] On Hans Kaschauer and his father Jakob Kaschauer, who painted the large panel of the high altar between 1445 and 1448, see Perger 1988, 84.

[8] Schütz 1980, 14.

[9] Mayer 1880; Schusser 1986, 66, no. 31/1 (Richard Perger). The university confirmed this regulation on 14 April 1411: see Uiblein, Acta Facultatis 1385–1416, 355.

[11] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 15; Czernin 2011, 59.

[12] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 25.

[13] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 29.

[14] See Lind 1860, 11; Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1; Perger/Brauneis 1977, 275.

[15] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1.

[16] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 1935.

[17] Vienna City and State Archive, Charter 1935, 21 November 1412; see also Schusser 1986, 139, no. 115.

[18] Boyer 2008, 25.

[19] An attempt to distinguish between chapter cantor (“Sangherr”) and school cantor is made by Mantuani 1907, 287 f.

[20] Zschokke 1895, 25–48; Flieder 1968.

[21] Grass 1967, especially 464–467.

[22] Flieder 1968, 140–148, especially 148.

[23] Edited by Ogesser 1779, Appendices X and XI, 77–83. See also Flieder 1968, 155, 158–160.

[24] A statute from 1367 stipulated that the roles of “choirmaster” (magister chori) and dean should be united in one person (Göhler 1932/2015, 141 f.), which, however, apparently did not occur (Flieder 1968, 173 f.).

[25] Mantuani’s (Mantuani 1907, 288) mistaken equation of “choirmaster” with “cantor” has often been repeated. The German term for the latter was “Sangherr”. Ulreich senior (1365?) was “magister chori et cantor” (Göhler 1932/2015, 142 and fig. 11), i.e. the two titles were not synonymous. On the correct use of the terms, see Ebenbauer 2005, 14 f. (choirmaster responsible for the parish), although Mantuani is cited there without contradiction.

[26] On the location of altars and chapels, see Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61–63. I am sincerely grateful to Prof. Barbara Schedl for her advice in this regard.

[27] Ogesser 1779, 80–82. See the list of procession participants from a Liber ordinarius of St Stephen’s (» A-Wn Cod. 4712): » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[28] Zschokke 1895, 30–46; Flieder 1968, 254–266.

[29] Zschokke 1895, 33.

[30] In ecclesiastical service regulations, the Latin equivalent “alta voce” was traditionally used.

[31] Zschokke 1895, 37.

[32] Zschokke 1895, 40.

[33] Zschokke 1895, 84–91.

[34] Raimundus Duellius, Miscellanea, Augsburg/Graz 1724, Vol. II, 78 and 82.

[35] “Ne quis eciam nimium voces agitare aut in altum audeat elevare habeatque et cantum Bassum et nimis clamorosum ad medium reducere.” (Zschokke 1985, 89 f.) See also Rumbold/Wright 2009, 44.

[36] Archdiocesan Diocesan Archive Vienna (A-Wda), Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 107r.

[37] Grass 1967, 482–487.

[38] On 12 March 1421, over 200 Viennese Jews were burned in Erdberg by order of Duke Albrecht V, as reported, among others, by theology professor Thomas Ebendorfer (Lhotsky 1967, 370 f.).

[39] Zapke 2015, 87 f.

[40] Gall 1970, 85–86; Flotzinger 2014, 44–47, 54 f.

[41] Gall 1970, 34, 86 f.; Zapke 2015, 88 f.

[42] Pietzsch 1971, 27 f.

[43] Mantuani 1907, 283 and note 1; Enne 2015, 379 f.

[44] See Strohm, Ritual, 2014 on the temporal awareness of ecclesiastical regulations.

[45] “Canons” here refers to the “octonarii”, the priests of the collegiate chapter entrusted with pastoral care.

[46] A-Wda, Charter 13391028; see Currency: 1 pound (tl.) = 8 large (“long”) shillings (s.) = 240 pfennigs (d., denarii).

[47] Camesina 1874, 11, no. 36. The distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor is convincingly demonstrated in Göhler 1932/2015, 228 f.

[48] A-Wda, Charter 14200525; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/14200525/charter [02.06.2016].

[49] Camesina 1874, 21, no. 94.

[50] Camesina 1874, 21–23, no. 96.

[51] Accounts of the churchwarden’s office of St Stephen’s (in the Vienna City and State Archive), see Uhlirz 1902. Extracts from the account books of St Michael’s in Schütz 1980.

[52] Schütz 1980, 124. Schütz 1980, 15, mistakenly equates the schoolmaster with one of the two cantors.

[53] See Uhlirz 1902, 251 and elsewhere. Knapp 2004, 268, interprets this as a Marienklage (Lament of Mary), which is less likely from a liturgical perspective.

[54] Uhlirz 1902, 364, 384. The Easter sepulchre was an artistically crafted sculpture.

[55] On the locations of the organs, see also Ebenbauer 2005, 40 f.

[56] Uhlirz 1902, 337 (1417).

[57] For example, 1415: Uhlirz 1902, 299.

[58] Uhlirz 1902, 267 (1407).

[59] Vienna City and State Archive, 1.1.1. B 1/ Main Treasury Accounts, Series 1 (1424) etc.: hereafter abbreviated as OKAR 1 (1424) etc. (» A-Wsa OKAR 1-55).

[61] For detailed information on » A-Wn Cod. 4712 see Klugseder 2013; see also » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession. The liturgy of the St Stephen’s chapter is represented by the “Turs Missal” (c. 1430, produced under Provost Wilhelm von Turs), which still belongs to the Archiepiscopal Chapter and is of particular interest for art history.

[62] A-Gu Cod. 756, fol. 185r; see » A. Weihnachtsgesänge.

[63] The former is the earliest dated addition, indicating that the codex must have been created before 1404.

[64] However, the Sunday Vocem iucunditatis was dedicated to St Koloman (» A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r).

[65] For polyphonic conclusions to monophonic plainsongs, as seems intended here, there is evidence from the fourteenth century in France and Italy.

[66] The procession descriptions in the original corpus of » A-Wn Cod. 4712, a Liber ordinarius of the Diocese of Passau, replicate word-for-word the regulations for Passau itself (courtesy of Robert Klugseder), but are also applicable to Vienna due to the similar ecclesiastical topography of both cities. Added marginal notes clarify the route descriptions with direct reference to Vienna: Klugseder 2013 devotes a separate chapter to the Vienna-related marginalia in Cod. 4712. (See also the digital edition of the Passau Liber ordinarius, http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.passau). The Corpus Christi procession is represented in Cod. 4712 only by a brief marginal note on fol. 67v. However, the list of participants appears in the appendix (fol. 109r), edited in » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[67] Camesina 1874, 24, no. 101.

[68] Camesina 1874, 26, nos. 113 and 114 (12 and 13 December 1404).

[69] Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50 (Lohrmann).

[70] The claim that the Dorothea Altar stood in front of the rood screen (Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61 and note 214) cannot be derived from the records of 1403–1404. The altar’s income belonged “to the school corporation”, which in this context did not refer to a “brotherhood of pupils” (Lohrmann in Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50), but to the school building itself.

[71] Not to be confused with a canon of the same name, Peter of St Margrethen, active in 1399.

[72] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, nos. 2159 and 3076. 1449: OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 28v.

[73] Some of the information in Brunner 1948 is outdated.

[74] Göhler 1932/2015, 228, no. 98.

[75] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2978; a mention of “Peter Marold, cantor” in OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 19v, may refer to another cantor of the same name or be retrospective.

[76] All except Neuburg are listed in Czernin 2011, 87 f. This list also includes the chapter cantors Ulreich Musterer (†1426), Wolfgang von Knüttelfeld (†1473), Hanns Huber (1474), Brictius (1470s), and Conrad Lindenfels (1479–1488, previously school cantor 1449–1457); a “Kaspar” (1448) may be identical with choirmaster Kaspar Wildhaber (1423/24). The additional names in Flotzinger 2014, 57, note 49, all refer to “choirmasters”, whom Flotzinger, following Mantuani 1907 and Flieder 1968 mistakenly equates with cantors. See Ch. The institutional foundation of the St Stephen’s chapter.

[77] Melk, Abbey Archive, Charters (1075–1912), no. 1436 I 27, http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-StiAM/archive [02.06.2016].

[78] OKAR 5 (1438), fol. 92r.

[79] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 98r, and OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 111r.

[80] The latter note is based on kind information from Prof. Barbara Schedl, Vienna.

[81] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2656 (3 July 1438). Other, partly contradictory, details cited in Ebenbauer 2005, 38 f.

[82] A-Wda, Charter 14401105.

[83] See also Flotzinger 2014, 56 f.

[84] Boyer 2008, 36 f.

[85] Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1. On Martin von Leibitz and his Caeremoniale (A-Wn Cod. 4970), see Schusser 1986, 82, no. 65, and » A. Melk Reform.

[86] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 97v. The cantor received 60 d.

[87] For example, OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 112v (five weeks; from November before St Martin’s Day to St Lucy’s Day, 13 December).

[88] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 139v. In addition, 24 “peace masses” were sung daily until the Friday after Laetare (4th Sunday in Lent), for which “Hermann and the boys were paid 32 d. for each mass sung”.

[89] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 140r. The cantor received 21 d. for each “votive”. The dean, levites (probably choirboys), sacristan, and organist are also mentioned.

[90] For example, OKAR 9 (1445). The (unnamed) cantor received 3 s. (= 90 d.).

[91] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 3, no. 3848; Camesina 1874, 92–93, no. 437.

[92] OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 37r.

[93] As often stated in older literature, e.g. Strohm 1993, 507. Corrected in Rumbold/Wright 2009, 47.

[94] Camesina 1874, 78–80, no. 364 (1445, undated).

[95] See Weißensteiner 1993.

[96] OKAR 9 (1445), fol. 51r; the city accounts for 1446–1448 are lost. See Rumbold/Wright 2009, 48–50.

[97] OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 32r.

[98] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 3333 (for 1449); OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 41r.

[99] Zschokke 1895, 375; Rumbold/Wright 2009, 50–51. Lindenfels quickly became unpopular after his installation in 1479 by claiming, as chapter cantor, the right to choose his canon’s residence ahead of more senior canons (A-Wda, Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 18r).

[100] OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 82v. The total cost for the carpenter and locksmith (for iron bars to secure the choir books) amounted to 160 d.

[101] OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 118v. The total cost for the carpenter and painter amounted to 95 d.

[102] OKAR 16 (1458); OKAR 36 (1474), fol. 22r.

[103] OKAR 42 (1478), fol. 32v.

[104] Text provided, among others, in Mantuani 1907, 285–287; see also Gruber 1995, 199; Flotzinger 2014, 58 f.

[105] See Strohm 2014.

[106] Uhlirz 1902, 477.

[108] A-Wda, Charter 15060119; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/15060119/charter [02.06.2016].

Recommended Citation:

Reinhard Strohm: “Musik im Gottesdienst. Wien ”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musik-im-gottesdienst-wien-st-stephan> (2016).