Musical Homage Gifts for Maximilian I.

On the Musical Sources of Maximilian's Court Chapel

Emperor Maximilian I pursued extensive cultural projects throughout his life. He staged himself, among other things, as a lover and promoter of music: for example, in weisskunig (» Abb. Weißkunig Blatt 33) or through the depiction of various carriages in the triumphal procession, which representative let his various music ensembles parade (» I. Instrumentalkünstler bei Hofe). He maintained (at least) one court chapel with well-trained singers and instrumentalists (» I. Instrumentalkünstler bei Hofe), who regularly had to travel with him.[1] And he endowed foundations and scholarships for polyphonic singing of masses (with and without organ), for example in Bruges and in Hall in Tyrol (» D. Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens, » D. SL Waldauf-Stiftung).

Contrary to this, it is peculiar that hardly any musical sources from Maximilian’s court have survived. Although the court had a musical scriptorium – Ludwig Senfl (» G. Ludwig Senfl) laimed that he alone had written „sechzechen gesang Buecher“ as “Notist”,[2] and there must have been many more. However, all the music manuscripts that originated there are lost; they did not survive in the holdings of the Bavarian State Library as was believed since Martin Bente’s dissertation of 1968.[3] [4]

Thus, in trying to get an impression of the liturgical and sacred music repertoire of the court chapel, sources must be used that are most likely indirectly connected with the court, for example, because it could be shown that they were created as copies of court sources – whereby the compositions were partly also edited or modernized. Among others, the following sources are closely connected to the Maximilianic repertoire according to current research: the choir book of the Innsbruck schoolmaster Nicolaus Leopold, in which various personalities noted the repertoire of the Innsbruck court or the cantory of St. Jakob over decades (» D-Mbs Mus. Hs. 3154);[5] the „Augsburger Liederbuch“ (» D-As Cod. 2° 142a), in which – as in the “Codex Leopold” – both secular[6] and sacred compositions are recorded; the utilitarian manuscripts among the “Jena Choir Books” (» D-Ju Ms. 30–33 and » D-WRhk Hs. A), some of which were produced as copies of Maximilianic sources for use at the court chapel of Elector Frederick the Wise;[7] a manuscript composed of various fascicles around 1520 („Codex Pernner“; » D-Rp C 120)[8] and finally, numerous Munich choir books that contain many compositions by Heinrich Isaac (» G. Henricus Isaac) (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 31: » Abb. Introitus Resurrexi; D-Mbs Mus. ms. 35–39; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 53; » G. Ludwig Senfl).[9] Additionally, there are the representative motet prints Liber selectarum cantionum; (Augsburg 1520; » Abb. Liber selectarum cantionum) and the famous, posthumous print titled » Choralis Constantinus of Isaac’s Proper settings in three volumes (» G. Henricus Isaac, Kap. Isaac als Hofkomponist Maximilians I.). Of course, with all these (and many other potential) sources, research must always plausibly explain the nature of the connection to Maximilian’s court – which is more or less conclusively done on a case-by-case basis. Thus, the musical source situation for the repertoire at the Maximilian court forms a complex puzzle – and many pieces are certainly irretrievably lost.

There are two exceptions: a print dedicated to Maximilian and his grandson Charles (» D. Musik für Kaiser Karl V.) with two motets explicitly tailored to Maximilian (cf. Kap. Gedrucktes mehrstimmiges Herrscher- und Marienlob) and a music manuscript (» A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495; cf. Kap. Ein Geschenk für den frischgebackenen Kaiser: Das Alamire-Chorbuch A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 and Kap. Zum Repertoire der Handschrift A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495) from the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript complex, which reached Maximilian during his lifetime and whose usage marks give the impression that it was used intensively.

A Gift for the Newly Minted Emperor: The Alamire Choir Book A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495

The choir book A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 belongs to a group of more than 60 surviving choir books and partbook sets that are known in current research as “Burgundian-Habsburg music manuscripts”.[10] These manuscripts were produced in a highly professional scriptorium located in the vicinity of the Burgundian-Habsburg courts of Archduke Philip the Handsome, Archduchess Margaret of Austria, and Archduke Charles (the later Emperor Charles V) in Brussels and Mechelen. The music manuscripts, copied from around 1495 to 1534, initially on parchment, i.e., the highest quality material, are sometimes elaborately illuminated and served in Habsburg circles as valuable gifts. The splendid manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 is the first choir book from this scriptorium, produced under the direction of the professional copyist, singer, and diplomat Petrus Alamire.

The » Abb. Kyrie Salve diva parens shows the richly illuminated opening pages of the choir book, which comprises a total of 105 folios (i.e., 210 pages). The miniatures show, in the upper left, the scene of the birth of Christ (Christmas); in the upper right, Emperor Maximilian in prayer, behind him his guardian angel; in the lower left, the coat of arms of Emperor Maximilian; in the lower right, the marital coat of arms of Maximilian and his wife Bianca Maria Sforza. Based on the heraldry, the creation time of the manuscript can be narrowed down to the period between spring 1508 (Maximilian’s proclamation as emperor) and December 1510 (the death of his wife)(» D. Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens).[11]

The musical text is – typical for the time – notated voice by voice in individual reading fields, not in a score: in the upper left, the discantus (the highest voice), below it the tenor (Nota bene: with the underlaid text “Salve diva parens”, not “Kyrie eleyson”!), on the upper right side the altus (here designated as “Contra[tenor altus]”), below it the bass. Such an arrangement is called “choir book notation”. A large ensemble (choir) could perform the various voices from this one book (» Abb. Kaiser Maximilians Kapelle), and the participation of individual instruments with the singing voices was conceivable and is iconographically documented (» Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei).

On the Repertoire of the Manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495

With the exception of the first composition, Jacob Obrecht’s Missa Salve diva parens (» D. Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens), all the masses recorded in the Viennese splendid choir book A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 are highly modern works created by contemporary composers who were (in the narrow or broader sense) associated with the French court: Antoine Févin, Loyset Compère, Antoine Bruhier, Pierrequin Thérache, and – the famous, still living and intensively received at the French court – Josquin Desprez.[12] Compared to earlier manuscripts from the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscript complex, the extraordinarily strong presence of modern French repertoire represents a striking change.

The reason for this repertoire change seems to lie in the political events of 1507/08: Maximilian had been decisively striving for the imperial crown for some time, which was successfully prevented by the French with their allies, the Venetians. Thus, a war seemed inevitable to Maximilian, and at the Diet of Constance in 1507 (» D. Isaac und Maximilians Zeremonien, Kap. Musik für den Konstanzer Reichstag 1507) he initiated a smear campaign against the French and Venetians. They ultimately prevented Maximilian from traveling to Rome and thereby from being crowned emperor by positioning almost ten thousand men in the Verona area. Finally, on February 4, 1508, Bishop Matthäus Lang was able to proclaim Maximilian as the elected emperor in a solemn ceremony in Trento Cathedral and announce his right to the imperial crown. The Pope confirmed the new imperial title.[13]

Soon after, in June 1508, the newly crowned Emperor Maximilian traveled to the Netherlands. His daughter, Archduchess Margaret, prepared a fundamental political shift there, a reconciliation with France. After weeks of negotiations in autumn 1508, an agreement was finally reached on December 10, leading to the “League of Cambrai,” which was announced during a festive service in the cathedral there. Maximilian signed the treaties on December 26, 1508, and ratified the league at the Brussels court on February 5, 1509. Officially, it represented a pact against the Turks, but in reality, it was also an attack pact (with the stronger of the formerly allied enemies) against the Venetians. For King Louis XII of France as well as for Maximilian, this meant a radical reversal of previous alliance policies. The current “French” repertoire of the manuscript A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 seems to directly reflect this fundamental political shift: The repertoire apparently acquired during negotiations with the French court and incorporated into the manuscript can be understood as a reflection of the new political and intellectual orientation that decisively shaped Europe at that time for years to come – and remained present in the Burgundian-Habsburg manuscripts for a long time, starting with A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495.

Printed Polyphonic Praises of the Ruler and the Virgin Mary

During his visit to the Netherlands as the newly proclaimed emperor (vgl. Kap. Zum Repertoire der Handschrift A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495) Maximilian also made a splendid visit to the city of Antwerp in September 1508, ahead of the negotiations with France. First, he invoked the Holy Spirit for his assistance there; then he turned to the Virgin Mary and sought to place his activities under her protection with the motet Sub tuum presidium. The set Sub tuum presidium (“Under Your Protection…”) is an old Marian prayer that was evidently significant for Maximilian (see J. Body and Soul). During this visit, his grandson Charles (» D. Musik für Kaiser Karl V.) was also appointed as Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire.

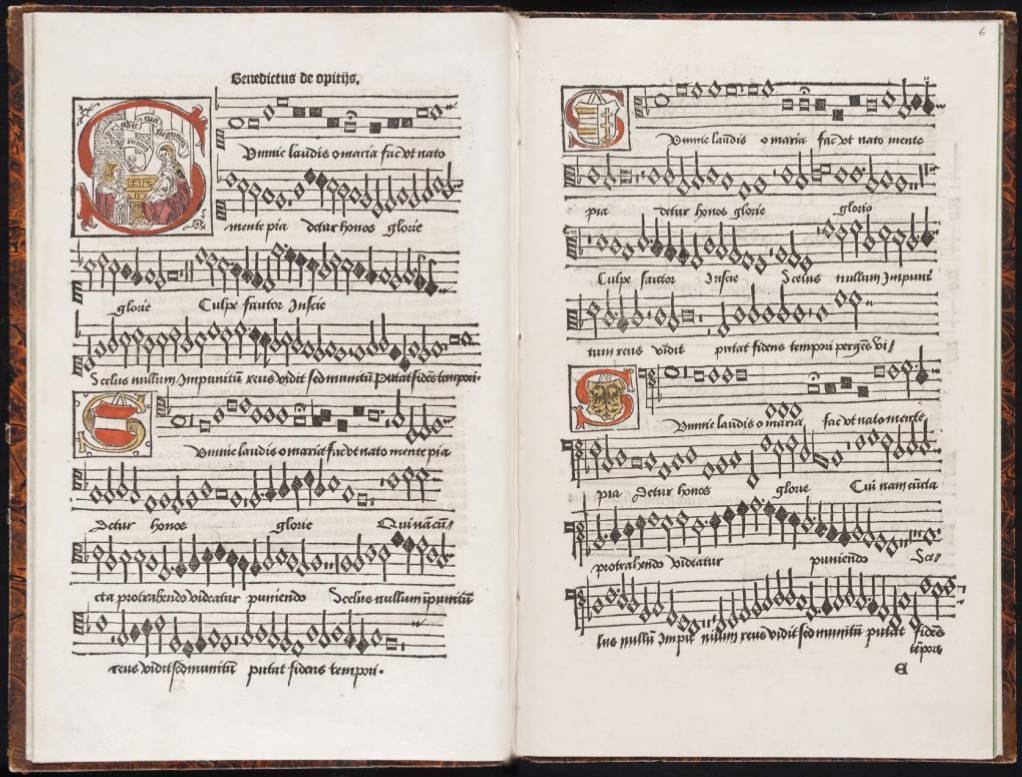

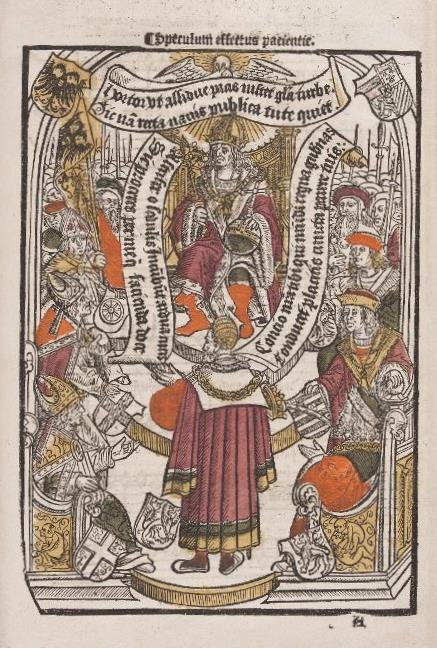

When in February 1515 in Antwerp the accession of the 15-year-old Charles as Duke of Burgundy was staged, the opportunity was seized to medially recall and inscribe in history the last significant presence of Maximilian and Charles in the city (that of 1508). A 40-page print was produced with the title » Unio pro co[n]servatio[n]e rei publice / Lofzangen ter ere van Keizer Maximiliaan en zijn kleinzoon Karel den Vijfden, which contains praises of rulers, God, and Mary in various text types, images, and music:[14] laudatory poems, humanist letters, prayers, full-page woodcuts, and the two motets Sub tuum presidium and Summe laudis o Maria. With this, the Antwerp printer Jan de Gheet presented the earliest print of polyphonic music in the Netherlands in 1515.[15] The 17 pages with notes – like in A-Wn Mus.Hs. 15495 in choir book arrangement – and text are made in block printing (woodcut) (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria).

In the print documenting the events in Antwerp from the year 1508, the merits of Maximilian (for peace in the empire, unity among princes, and the promotion of the common good[16]) are the main focus, which he was able to achieve through the intercession and vigor of the Virgin Mary (see e.g. » Abb. Maximilian I. und Kurfürsten). The print reflects a ruler’s understanding that was widespread at the time (illustrated in the initial at the beginning of the discantus of the motet Summe laudis o Maria: see Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, initial): the Holy Spirit sends his rays down upon Maximilian, depicted as the ruler of the world, to whom his high office – like many other rulers – was entrusted by God, and Mary provides him with her indispensable assistance in the exercise of his difficult office.

The centerpiece of the homage print is the second motet Summe laudis o Maria, whose text “Summe laudis” was written by Petrus de Opitiis, the brother of the composer of both motets, Benedictus de Opitiis (* ca. 1476; † 1524).[17] The text of the motet is paraphrased and interpreted section by section in the print, and the motet is also introduced by a Latin poem that makes it clear that the thought process of the motet underlies the conception of the entire print.

The text “Summe laudis” (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Text) begins with great praise of Mary and then addresses in various paraphrases the legitimacy of Maximilian as emperor[18] – which was quite significant in the historical context, as the rightful imperial coronation in Rome had been prevented –, and finally culminates in an extended praise of the emperor.[19] The structure of the text, with praise of Mary first and praise of the ruler second, thus resembles that of Heinrich Isaac’s motet Virgo prudentissima (» D. Isaac und Maximilians Zeremonien, Kap. Musik für den Konstanzer Reichstag 1507).

Visually, the intertwining of Marian devotion and the state-political and worldly dimension in the Antwerp print is emphasized by the fact that the initial of the motet Summe laudis shows Emperor Maximilian singing the words “Sub tuum presidium ad te confugimus” (» Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, » Abb. Summe laudis o Maria, Initiale) thus placing himself personally and actively under Mary’s protection. It is particularly noteworthy that the text creates the impression that the “Son of Mary” is evidently not just Jesus (who is never mentioned by name), but also the praised Maximilian (» D. Obrechts Missa Salve diva parens, Kap. „Mehrfacher Sinn“: Maria als Mutter des zukünftigen Herrschers).

Benedictus de Opitiis followed the structure of the text in his four-part setting and placed clear polyphonic cadences at the end of almost every text unit. He composed a strongly imitative four-part setting, as was typical for the motet genre at the time, and highlighted certain text passages particularly clearly through homorhythmic voice leading: for example, in the sonorous greeting section “Summe laudis o Maria […] glorie”, in the assurance of the battle in God’s trust (6th text section), and in the two final sections (13th and 14th), where the musical colon settings after “cunctipotem” and “Maximilianum” particularly emphasize the prayers that God, the Almighty, may eternally preserve the peace-bringing Emperor Maximilian and the imperial Austria.

[1] For this, see recently Gasch 2015, especially pages 362–371.

[2] Petition to King Ferdinand I in 1530; A-Whh Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv, Niederösterr. Kammer, Rote Nr. 7. Reprinted in Birkendorf 1994, Vol. 3, 248.

[5] Strohm 1993, 519–522; Edition in 4 volumes: Noblitt 1987–1996.

[6] For the secular sources („Liederbüchern“) related to Maximilian’s court, see » B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Aufschwung der Liedkunst unter Maximilian I. and » B. Lieder 1450–1520, Kap. Liederdrucke.

[7] See Heidrich 1993.

[8] Birkendorf 1994. The compositions are often recorded without text.

[10] For this, see among others, Kellman 1999; Bouckaert/Schreurs 2003; Saunders 2010; Burn 2015.

[11] Lodes 2009, 248.

[12] Missa Faisantz regretz and Missa Une mousse de Biscaye – the latter of which, although passed down under Josquin’s name, was probably not composed by him.

[13] For the historical-political context, see among others, Wiesflecker 1971–1986, Vol. 4, 1–27.

[14] The print was produced in two editions (one with a summary in Dutch, the other with a summary in Latin) and is available as an annotated facsimile: Nijhoff 1925, with a translation of the two motets by Charles Van den Borren as an appendix. See also Schreurs 2001 and Wouters/Schreurs 1995. For a complete digital copy of the Latin edition, see: http://depot.lias.be/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE4756261.

[15] Earlier in Antwerp, a music print with the imperial coat of arms and that of the Margraviate of Antwerp had already been produced: » Principium et ars tocius musice, Antwerpen: Jost de Negker (c. 1500–1508). However, this is a representation of the Guidonian Hand with mensural notes and comments, not a polyphonic composition. See Schreurs/Van der Stock 1997; also a facsimile on page 173.

[16] Schlegelmilch 2011, esp. 443–447.

[17] Benedictus held the position of organist at the Antwerp Church of Our Lady from 1512 to 1516 and then went to the English court. Only these two compositions of his are known.

[18] Victoria Panagl particularly points out the lines “Ergo Cesar quum nec deus / rerum metas neque tempus / tuo dat imperio” (7th stanza; “Therefore, Caesar, because God sets no spatial or temporal limits to your rule”), which as a quotation from Virgil emphatically refer to Maximilian’s claim to power (as successor to the Roman Empire): In the Aeneid (1,278: “his ego non metas rerum nec tempora pono”), Jupiter speaks these words, looking ahead to the glorious rulers of the Roman Empire (see Panagl 2004, esp. 73–81, here 78).

[19] See Dunning 1970, 61–64.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Birgit Lodes: “Musikalische Huldigungsgeschenke für Maximilian I.”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musikalische-huldigungsgeschenke-fur-maximilian-i> (2017).