Children’s processions in Tyrol

Parish schools and communities

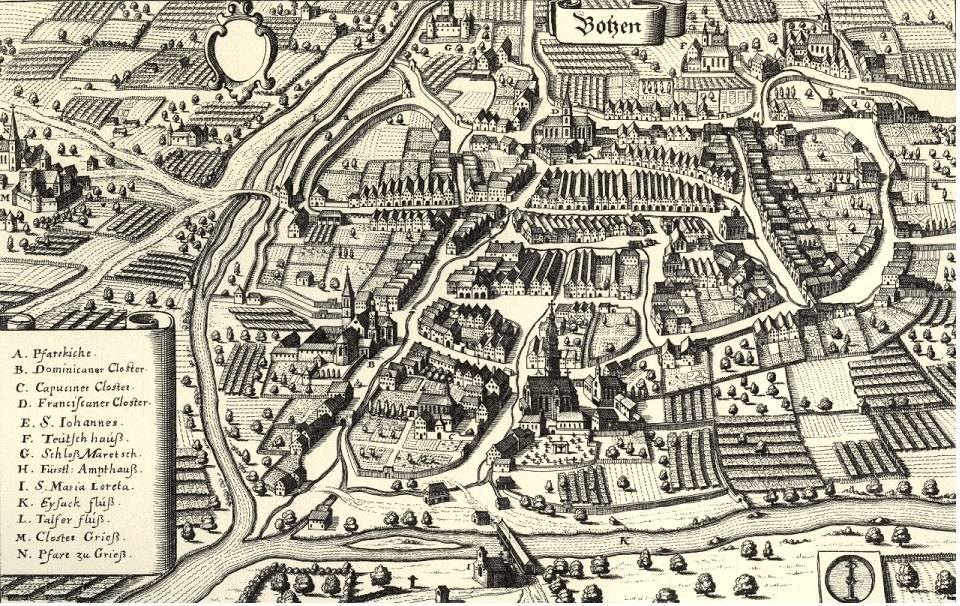

If we were present in a Tyrolean town in the fifteenth century, what we would hear most of the time would be the voices of children. Games, running, laughter, noises certainly filled the streets of the populated town centres, but children’s songs also played an important part in the life of the urban community. In fact, historical sources concerning Tyrol tell of numerous occasions of collective singing in public places, performed by the local schoolschildren. All education still took place in church schools: in the cathedral school of Brixen/Bressanone and in the many parish schools distributed in the area. The latter are documented in Tyrol since the thirteenth century;[1] they operated both within the largest towns such as Bozen/Bolzano, Merano, Innsbruck, Hall in Tyrol, and in many smaller centres.

The parish schools, which had been founded to educate young clerics, were increasingly influenced by the civic authorities and became, in fact, communal schools.[2] It is worth remembering in this context that the parish churches of late-medieval Tyrol functioned not only as religious centres, but also mirrored the social and economical identities of the civic and ecclesiastical communities that they represented.[3] It is thus no surprise that the musical activities of such a school, including its processions, were strongly conditioned by this interaction between civic and ecclesiastical powers. One example was the parish school of Bolzano, which in the fifteenth century was particularly active in music (» E. Bozen/Bolzano: Musik im Umkreis der Kirche). The rich documentation available today shows how the urban community organised, supervised and funded the local church school of St Mary’s (» E. Kap. Das Salve regina des Rats). The town authorities themselves exerted massive influence on the parish school; an example of this is the imposition, in 1479, of scholasticus (schoolmaster) Augustin Ayrinsmaltz on the Bolzano school by Duke Siegmund of Austria, Count of Tyrol. This nomination caused great dissatisfaction within the ecclesiastic and civic community of Bolzano and triggered a long, contentious quarrel between the schoolmaster, the town and the duke.[4] The maestro was in fact completely incompetent in music, so that according to the community he was quite unable to cover the task of schoolmaster.

Tyrolean sources for school processions

Various types of sources document the processions in which the pupils of the late-medieval schools took an active part with their singing. Among the oldest documents there certainly are the books called libri ordinarii (Ordinals), which were really manuals for the celebrations of a church or cathedral: they contain precious notes on the numerous processions which were held inside and outside the places of worship, on the various occasions of the liturgical year. For Tyrol, we have a few important sources of this kind, although they originated outside the time-frame considered here. Among them are the liber ordinarius (Ordinal) of Bressanone cathedral, from the beginning of the thirteenth century,[5] the so-called Brixner Dommesnerbuch (book of the Bressanone sacristan) of 1558 (>> A. Kap. Der Dommessner),[6] and the Directorium chori (Choir regulation) of the collegiate church of Innichen/San Candido, of 1617.[7] The Bressanone Ordinal lists the processions which the children carried out on special feasts of the liturgical year, following a tradition going back as far as the Roman-Germanic Pontifical of c. 960.[8] During Mass on the Saturday of the ember days (quatuor tempora) and on Palm Sunday, processions were held in which the boys of the cathedral school had to sing. This practice meant that the boys were in fact the protagonists of the performance of the gospel episodes: their very presence “dramatised” the gospel narration of Palm Sunday, conveying upon them and on their voices a highly symbolic role in the context of the ritual.[9] For the Mass on ember days, the Bressanone Ordinal states: “Nota quod hymnus trium puerorum Benedictus es domine sicut ordo iubet a tribus pueris, ubi fieri potest, debet cantari et interim nemo in ecclesia sedeat, quia pueri in camino ambulantes cantabant.”[10]

(Note that the hymn of the three boys, Benedictus es domine, according to the regulation of the Ordinal, must be sung by three boys, wherever possible, and meanwhile nobody may sit down in the church, as the boys were singing while walking by in procession.)

At another point in the Ordinal references are made to the pueri: for the feast of the Holy Innocents (28 December) it is stated at the very beginning and separately from all other regulations that they must celebrate the feast “according to custom”.[11] The book does not give any more detail, implying that the custom was well-known. It is clear, in fact, that the reference is to the practice of the so-called Episcopellus or Episcopus puerorum (Boy Bishop), of which the day of the Holy Innocents represented the high point. The festivities connected with the Boy Bishop (or School Bishop) began in Advent when, usually on the day of St Nicholas (6 December), a boy was elected who presided as “bishop” over a special celebration during the feast of the Holy Innocents. This practice was known all over Europe; it included processions in the church as well as outside in the streets.[12] In Bressanone, the feast of the Boy Bishop was abolished by episcopal decree in 1442, because of the irregularities which it caused, according to the church authorities, in the streets of the town from the beginning of Advent onwards.[13] It is therefore reasonable to conclude that until this date the processions lead by the Kinderbischof did take place in Bressanone, like elsewhere, on the day of the Holy Innocents and other feast-days; the participants were the children of the school.

As Tyrolean sources tell us, another procession of schoolchildren, clad in red gowns, was held at Sterzing/Vipiteno on the day of St John the Baptist (24 June), to celebrate “sonnwend abend” (solstice evening).[14] This procession, just like the one of the Boy Bishop, represents for the modern observer the typical mixture of sacred and secular elements which is so characteristic of medieval rituality.

Nevertheless, the sources that are most interesting for us as they offer many notices about children’s processions in Tyrol are without any doubt the regulations for the schools and schoolmasters, to which we shall turn below. In addition, the account books, if extant, of the various institutions involved in the liturgical and musical activities of the school often provide precious information which completes and enriches the documentation already cited here (» E. Bozen/Bolzano: Musik im Umkreis der Kirche). We will finally mention the chronicles of travellers which have the advantage of presenting “live” descriptions of some performances in late fifteenth-century Tyrol whose protagonists were schoolchildren.

Ansingen: an introduction

The pupils of the church schools were in fact also protagonists of performances which were not religious or liturgical: they were called “Ansingen” (“singing at”; serenading).[15] This practice, disseminated throughout the German-speaking region and in other centres in Europe, consisted of vocal performances of the students in non-liturgical locations such as streets, squares, inns, castles, town halls and hospitals (» E. Kap. Das Bozner Ansingen); these were held periodically during the year, on special feast-days and for visits of high-ranking personalities. As reward for their vocal display, the choristers – who could be pupils only or sometimes include their instructors – received gifts and money. This practice, widespread in the Middle Ages and also known under the name of “Kurrende” (wandering choir), received a strong impulse during the Protestant reforms and survives to this day in some areas of Northern Germany.[16] In Tyrol, the custom is documented and described in some travel diaries of foreign visitors who traversed the region in the late fifteenth century. Venetian ambassadors, heading for Germany in June 1492, stopped over in Klausen/Chiusa, a town north of Bolzano, in the tavern called the “Agnus Dei”, and recorded in their travel diary a vocal performance given in their honour by pupils and masters of the local school (» D. Advenisti. Fürsten und Diplomaten auf Reisen). The ambassadors were surprised by the high musical standards of the small group, which consisted of five children and two masters, performing music “with admirable consonance” – thus presumably in polyphony. The diary specifies the music performed in sufficient detail to allow for a tentative identification of at least one of the pieces: it was “a certain song resembling the trumpets of a battle” (un certo canto simile a trombette di battaglia) – perhaps a composition “ad modum tubae”. At the end of this little concert the enchanted ambassadors lavishly recompensed the children and their masters for their excellent performance. This detail draws attention to a fundamental aspect of Ansingen: that of the very real need to collect money to fund the masters and poor pupils of the school.[17] In many cases – presumably including the Klausen performance cited here – the schoolmasters accompanying the children also benefitted of this income, whereas in other circumstances the money received was to be divided equally among the pupils. The school regulation of Bolzano, 1424 (see below), stipulates the distribution of the money very precisely. Nevertheless, the rules for this distribution underwent changes as time went on (» Kap. Das Bozner Ansingen). Sources tell us that in some localities in Tyrol, Ansingen remained alive until the later eighteenth century.[18] The documents inform us that the custom was very ancient but, over the centuries, also underwent abuses (it was occasionally transformed into unlawfaul aggressivity) and “irregular” competition; thus, at Innsbruck and Hall i. T. in the seventeenth century, the boys of the parish school who practiced Ansingen every week were rivalled by the students of the local Jesuit College.[19]

The school regulation of Bolzano, 1424: Ansingen and recordatum

A source of primary importance for the reconstruction of the Ansingen practice in Tyrol is the Schulordnung (school regulation) of the parish school of Bolzano of 1424.[20] Reputedly the oldest school regulation of the region, it is contained in the Urbar (catalogue of rental income, rights and duties) or liber jurium of the Bolzano parish church (» Fig. Haslers Urbar), compiled in 1453-1460 by the church warden Christoph Hasler jun., which is held at the National and University Library of Strasbourg (» Kap. Das Urbar der Bozner Pfarrkirche).[21] Its contents answered a need to regulate the civil and ecclesiastical life of a mid-size town in rapid development, where the church and the secular authorities fulfilled closely intertwined functions.[22] The school regulation (named Statuten der Schulen on f. 132v, where also the date of 1424 is recorded) is organised in five chapters (f. 128r-136v) which precisely stipulate, among other things, the incomes of the schoolmaster and the Junkmeister. From this we learn that the Junkmeister (succentor) did not receive the same benefices and annual salaries as the schoolmaster, but that part of his livelihood derived directly from the income earned through singing in public (» Kap. Junkmeister, Astanten und das Musikstudium der Knaben). For this reason, too, the regulation devotes much space to the times and manners of Ansingen which in fact represented a primary source of sustenance for the school of Bolzano. Other chapters of the Urbar offer interesting details about the processions in which the schoolboys were singing. There are, for example, chapters (in the manuscript directly preceding the school regulation) which deal with the duties and incomes of the sacristan: these mention among other activities the daily procession after the morning Mass service – which the sacristan had to announce with a particular sound of the bell – and the great procession of Palm Sunday, likewise accompanied by solemn and extended bell-ringing.[23]

As regards Ansingen, the regulation state that according to ancient tradition the choir went out both weekly and annually. The chapter on the income and duties of the Junkmeister (Hye ein vermercht die nüctze vnd välle, die ainem yeden junchkmaister zugehorn, f. 133r), establishes that the Ansingen in the evenings, called “recordatum” or “recordieren”, was to be carried out every week by the poor students of the parish school on Saturday evening, but only for an hour.[24] The term “recordatum” was derived from the noun recordatio – the practice, widespread since the earlier Middle Ages, of welcoming and celebrating citizens or high-ranking personalities with the recitation of poems and song. The collected money went to the Junkmeister, who assigned to the poor students one Fierer for every Kreuzer earned (i.e., 4 pennies of 12, “kreuzer” being treated here as equivalent to “groschen”).

Item so sullend dy arme(n) knab(e)n des abends Recordatu(m) gen dy wochen nur ain stund und nicht mer vnd was sy ersingen, das sol dem Succe(n)tor(i) geuallen, also das der Succe(n)tor von ainem ygleich(e)m kreucz(er) 1 fir(er) den armen knaben davon geb.

In this way, the school regulated and legitimised the weekly non-liturgical singing of its poor students who, with the generous and active support of its community, could safeguard with their singing a regular income, which they needed to maintain themselves in their studies. The same activity provided part of his income to the Junkmeister. The regulations also stipulated that the poor schoolboys and the grossen gesellen (adult helpers, Astanten) could go on the Recordatum eight further times during the year. What they collected for their singing on those evenings was to remain entirely for them:

Item auch mugent dy arme(n) knab(e)n vnd and(er) grosze gesel(en) da auff der schule in dem jar zu acht mal gen Recordatu(m) in selbs und was sy dy acht mal ersing(e)n des abents, das sol in allain beleiben.

The regulation also defines the use of the money earned by the sons of the bourgeois citizens in the Ansingen performances of Christmas time (on which, see below). They had to submit 5 £ to the Junkmeister, but could keep the remaining amounts, dividing it equally among themselves:

Item so sol der Jungmaist(er) von dem ansing(en) gelt hab(e)n V libras p(er)n(er), das dy burg(er) knaben zu weinachtt(e)n ersingen und was vberteur ist, das sullen dy knab(e)n vnd(er) in selb(er) geleich tailen.

The schoolmaster had the right to assign to the Junkmeister further amounts from the money earned in the cited activities:

It(e)m zu behaltt(e)n dem Succe(n)tor, ob im der Schulmaist(er) vb(e)r alle egenan(ten) seine zuvälle ain prerogatif tat, das mag jm auch werden.

Finally, it is ruled (f. 134r) that after Sunday Mass the grosse Gesellen (adult helpers) could have dinner with the Junkmeister and to go to sing, outside the parish house, the Marian antiphon Nigra sum sed formosa.[25] For this service the Junkmeisteri received 13 Fierer. Of these, he had to give six to the helpers for wine, but they could all drink it together:

Item so sullend dy gross(e)n gesell(e)n des Suntags zu(m) ambt abentt essen mit de(m) Jungmaister und für den pfarhoff gen sing(e)n dy antiphona Nigra sum s(ed) formosa vnd dauon hatt der Jungmaister xiii fir(er) und sol dauo(n) den gesell(e)n vi fi(rer) geb(e)n vmb wein vnd dy mit in vertringkhen.

Ansingen itineraries at Christmas time

The following chapter of the regulation (» E. Kap. Das Urbar der Bozner Pfarrkirche) is entirely concerned with the great Ansingen processions at Christmas time, which took place in the town and in the near mountains on the four days following Christmas, namely St Stephen’s Day (26 December), St John the Evangelist’s Day (27 December), Holy Innocents’ Day (28 December) and St Thomas’s Day (29 December). The title of this chapter is as follows (f. 135r):

Hye ein vermerchkt die ordnung, die man mit ansingen auf Vns(er) lieben frawn werch zu den weyhennachtt(e)n in der Stat und ausserthalb(e)n gehaltt(e)n hat mitt erb(er)n pawleutten, als von alter gewonhait ist.

(Here is recorded the regulation which has been observed with Ansingen by the church fabric of Our Lady’s at Christmas in the town and outside, with honorable house-owners, as is ancient custom.)

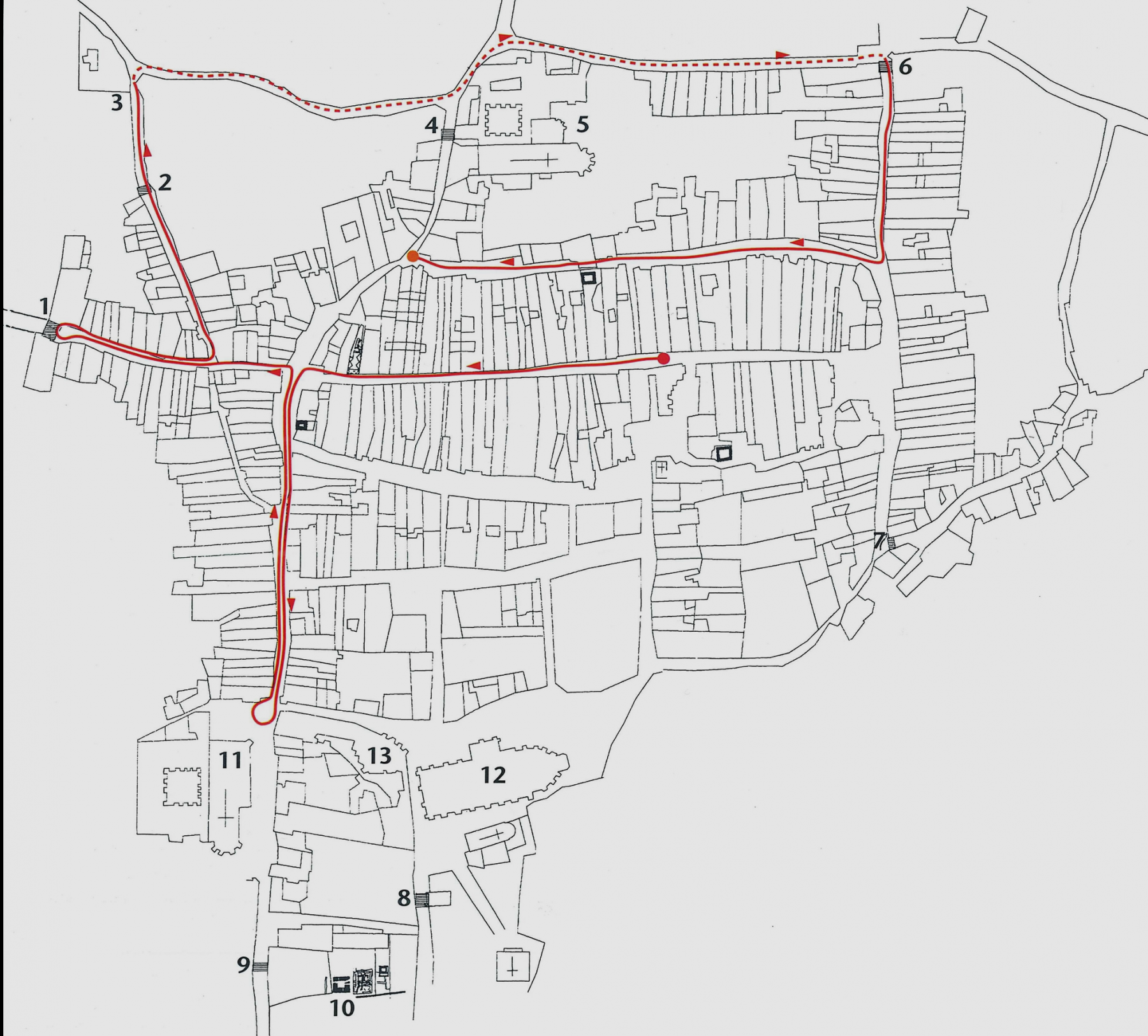

The ensuing text is a document of outstanding historical value for its wealth of information and descriptive accuracy, unparalleled in Tyrol. It identifies, in fact, the circuits, the streets and the names of the houses in front of which the singers had to stop and perform during their processions in the days after Christmas. The description provides a physical and musical map of the fifteenth-century town and at the same time opens up a sketch of contemporary society. Michela Paoli-Poda has transcribed the regulation and aimed to reconstruct the itineraries of the first three days, with the help of old town maps.[26] » Fig. Ansingen itinerary 27 December and » Fig. Ansingen itinerary 28 December present the maps of the second and third days; we give in the appendix a new transcription of the original narrative. Although the original text contains some passages that are difficult to interpret today – the topographical references differ from the present ones, and indeed the town has changed much – it allows us to follow the Ansingen procession virtually, helped by the modern street names.

On the first day (St Stephen’s Day, 26 December) the procession began after the Vespers service. It went first through the commercial centre of the town, along the present Via dei Portici (Laubengasse). Starting from Piazza Erbe (Obstplatz), the procession went eastwards through almost the entire street towards Piazza Municipio (Rathausplatz), coming to a halt near the New Chapel (at the height of Piazza del Grano, Kornplatz) and returning in the parallel street.

On the second day (St John’s Day) the singing procession began already after High Mass (Fronambt).

The itinerary was definitely longer and more challenging. The map shows something like a star-shaped itinerary, which had its centre at Piazza Erbe. From here, the first excursion wenth south, through the Schustergasse (now Goethestrasse) towards the Piazza dei Domenicani (Dominikanerplatz), reversed there and returned to Piazza Erbe through the parallel street. Then the procession went east until the eastern towngate (Hurlachtor) and back, but before re-entering Piazza Erbe, a smaller group of singers, probably two or three, was directed towards the St Martin’s brook (which then provided the town with fresh water), while the remaining group went towards the Franciscan monastery. At this point the description becomes somewhat unclear, so that the itinerary of the singers cannot be reconstructed precisely, but it moved in the area of the Parfusser (Franciscans) to terminate in the Obern Graben (today’s Via Streiter).

On the third day (Holy Innocents Day) the singers began after High Mass and, as on the previous day, their itinerary was very long.

The starting point was the Wangergasse (same name as today) near Porta Vintler (Vintlertor), thus not far from the place where the procession of the previous day had ended. From here, it went south along the Via Bottai (Bindergasse), and in a large curve towards west, it arrived at the parish church (cathedral today). From there, the procession continued towards the southern town gate, until the bridge over the Eisack/Isarco river, to return to the parish church the same way. Afterwards the singing continued in the new town and the Unterer Graben (south-west of the centre); on the same day a separate action after vespers was the Ansingen in the parish house and in the Holy Ghost hospital.

This is how the Ansingen was carried out within the town. In fact, for the fourth day (St Thomas of Canterbury, 29 December) the regulation ordered the children to go singing in the mountains (f. 135v), perhaps in Jenesien or on the Ritten, as was the old custom, but states that no church warden ever accompanied them:

It(e)m an dem vierd(e)n tag so gennd dy ansing(er)n an das gepirg, als von alter herchome(n) ist, do get kain kirchpräbst nicht mitt etc.

Feeding the Ansinger at Christmas

The chapter on the Ansingen itineraries in the Bolzano school regulation is followed by a brief but precise “Note regulating how one should deal, and has hitherto been dealing with, the food for the Ansinger at Christmas”, f. 136r.

Nota die ordnu(n)g, die man mit speyse den ansingern(n) zu weyhennachtt(e)n halten sol und gehaltten worden ist pis her etc.This specifies the due provisions of food for the singers at Christmas: on the different days, the singers should receive refreshments (“ain gutt merend”) but on the second and third days, they were given both a proper meal (“ain gutt mal”) after High Mass and a good refreshment – which were, however, the only provisions on these respective days.Item an dem ersten tag als an Sand Steffans tag so hebt man an zu singen für sich nach der vespern, da geitt ma(n) den ansingern ain gutt merend und damitt bestet es auff den tag, das ma(n) in nicht mer geit.It(e)m an Sand Johannes tag darnach für sich nach dem franambtt ain gutt mal und ain gut merend und damit bestet es auff de(n) tag, das man in nichts mer geitt.It(e)m an aller kindl(e)n tag nach dem franambtt ain gutt mal und ain gutt merend.Likewise, on the fourth day, “when the Ansinger brought back the money earned on the mountain, they were given a good refreshment”.

It(e)m wenn dy ansinger das ansingelt ab dem gepirg bringent, so geit man in ain guet merennd

The Ansingen repertory in Tyrol

The school regulation of Bolzano (» Kap. The school regulation of Bolzano) is regrettably not specific about the kind of songs performed during the Ansingen. The same silence also typifies the other Tyrolean sources of the time, except for the Venetian travel diary mentioned above. On the basis of the latter we may hypothesise, however, that since the late fifteenth century Ansingen in Tyrol comprised both monophonic and polyphonic music. The repertory probably consisted of more strictly liturgical items such as antiphons, responsories, hymns, cantica, sequences (and perhaps other sections of the Mass liturgy), as well as cantiones in Latin and German.[27] The typical medium for these performances was, in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, approximately that described in the ambassadors’ diary: four or five children together with two or three masters (succentors or older students). This formation allowed for a balanced rendering of three- or four-voice polyphony (» E. Kap. Das Bozner Ansingen).

The arrival of the protestant doctrine in Tyrol certainly affected the repertory of the Ansingen practice. This is evidenced by some Tyrolean documents of the later sixteenth century, which complain about the performance of Lieder and psalms in German, which were of “suspect provenance”.[28] Perhaps for this reason, the provincial council of the Salzburg archdiocese, 1569, decreed that only “Latin antiphons and Lieder” were henceforth allowed during Ansingen:[29] a sign that the repertory had by then been extended to other types of songs, which were resented by the church authorities.

Bolzano School Regulation for Christmas Processions, original and translation

The original text of the regulation for the Bolzano parish school (1424) for the itinerary of Ansingen processions after Christmas, 1424 (Hasler’s Urbar, f. 135r-v: » E. Kap. Das Urbar der Bozner Pfarrkirche).

Item so hebt man an an sand Steffanstag nach demCristag für sich nach der vespern zu singen an de(m) echawsam platcz, da Vlreich Gredn(er) inne sitczt, das Hainreichsam Ortt gewes(e)n ist, vnd singet ma(n) dyselbig(e)n contrat(e)ngancz herab hincz an die new capell(e)n vnd schlechtma(n) vmb in die and(er)n contratt(e)n hinauffwerts zu sing(e)nhyncz an das hawss Engleins noders, da latt man esansten auf denselbigen tag.(Item one begins on St Stephen’s Day after Christmas to sing separately after Vespers[30] near the corner house on the Platz, inhabited by Ulreich Gredner, which used to be Hainreich’s am Ortt, and one sings this same lane all the way down until the New Chapel, then turning around in the other lane upwards, singing until the house of Englein Noder, where one leaves it for the present day.)

Item auff den and(er)n nachst(e)n tag für sich nach dem frona(m)btso hebt man an zu sing(e)n an Engeleins noders hawssund also dy contratt(e)n gancz hinauff an platcz vnd anderselb(e)n seitt(e)n gein Härtlein Schmid dy Schustergassengancz hinab hincz an des spitals schenckhawss, do schlechtman über an d(er) Kälein oder Hanns Vintlers haws zusingen vnd dy and(er) gassen in Schustergass(e)n hinaufwertzan platcz vnd vo(m) platcz an derselbig(e)n seitt(e)n von des Rein(e)rsschuesters hawss hinauswertz durch dy auss(er)n flaischpanckfür das tor hincz an den zoll vnd vom zoll an d(er)selbig(e)n seit(e)nhereinwercz durch dy Flaischgassen wid(er) hincz an de(n) placz,so schickt ma(n) zwen od(er) drei, dy die Rawschgass(e)n ansing(e)nvnd die gassen an Sand Marteins pach hindurch hintzgenn parfuss(er)n. Indem so hebt man wider an zu sing(e)nhinaufwertcz ge(n)n parfussen vnd also vom platczpaid gassen zu singen hinaufwerts dy Hint(er)gassenhinab hincz an das haws des Andres am zoll. Darnachso hebt ma(n) an zu sing(e)n dy gassen aus, dy man haistam ob(er)n grab(e)n, do der Rittn(er) vnd Sigmun(d) am Turninne sitczent, do beleibt es an dem andern tag.(Item on the following second day, separately after High Mass, one begins to sing at Englein Noders house and thus the lane all the way up to the Platz and on the same side towards Härtlein Schmid the Cobbler’s lane all the way down until the hospital tavern, where one turns round to sing at the Kälein’s or Hanns Vintler’s house, taking the other Cobbler’s lane up again to the Platz, and from the Platz on the same side at Reiner Schuester’s house outwards through the exterior meat market before the town gate until the customs bar, and from the customs bar on the same side inwards again through Meat Lane again back to the Platz, where one sends two or three who sing in the Rauschgasse and the lanes along St Martin’s brook through to the Parfusser. Meanwhile, one begins again to sing from the Platz upwards towards the Parfusser, thus singing from Platz upwards both lanes; [then] the Hintergasse down until the house of Andres at the customs bar. After this, one begins to sing the rest of the lane called Am Obern Graben, where the Rittner and Sigmund am Turm are living, where the second day is completed.)

Item an dem dritten tag so hebt ma(n) an für sich nach demfronambt zusing(e)n inn Wang(er)gass(e)n an des Andres hawsam zoll pei Vintler tör vnd also paid gass(e)n mittainand(er)herab hincz an das tor, do man gett ge(n)n der nid(er)n pad-stub(e)n vnd von dem tor für Niderhawss dy gass(e)n durchhintz gen(n) der pharr(e)n vnd darnach dy gassen abhindo man gett in mairhoff vnd vom mairhoff singetma(n) dy paid gass(e)n an Eysagkprugkh(e)n vom Kerlein magman hincz an dy Plassemberg(e)rin herauf, darnachsinget man dy Newnstat aus vnd dy gass(e)n am vndt(e)rngraben, desselbig(e)n tags für sich nach vesp(er)n singt ma(n)im widu(m) vnd im Spital an.(Item on the third day one begins, separately after High Mass, to sing in the Wangergasse at Andres’s house at the customs bar, next to the Vintlertor, and through both lanes together down until the gate, where one goes towards the Lower Bathhouse, and from the gate in front of Niderhawss the lane through until the parish, and from the the lane down where one comes to the Mairhoff, and from the Mairhoff one sings both lanes to the Eysagk [Isarco] bridge; from the Kerlein may one go up until the Plassenbergerin. After this one sings throughout the Newnstat and the lanes at the Unterer Graben; on the same day, separately after Vespers, one sings in the parish house and the hospital.

[1] For a compact history of Tyrolean schools, see Augschöll-Blasbichler, 2019, 96-106 at 96-101, online, https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/qdi/article/view/2643 (April 2023). On music in the schools, see Post 1993; Herrmann-Schneider 2023, online ,https://musikgeschichten.musikland-tirol.at/content/musikintirol/musikinkloesternusw/musik-in-pfarrkirchen.html (April 2023).

[2] Cfr. Büchner 2019, 16-49 (Teil I); 94/1, 2020, 46-72 (Teil II); 94/2, 2020, 20-61 (Teil III); 94/3, 2020, 40-61 (Teil IV); 94/4, 2020, 28-71 (Teil V): in Teil I, 27, a few examples from Tyrolean schools are given.

[3] As underlined by Hannes Obermair, referring to the parish church of Gries near Bolzano, the “System Church” represents in the 15th century an “efficient mixture of cult, community, identity and economical sphere”: see Obermair 2012, 137-174 at 137.

[4] Büchner 2019, 27-28.

[5] Preserved at San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript vii a 10s. Transcribed by Gionata Brusa, online, Cantus Network. Libri ordinarii of the Salzburg metropolitan province, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:cantus .

[6] Modern edition in Hofmeister-Winter 2001. This regulation of the sixteenth century informs about various processions with the participation of children, and about the ancient, widely-known custom of “Kindelwiegen” (child-rocking) which at Bressanone was reserved for the masters and students of the cathedraL school: see » A. Kap. Kindelwiegen.

[7] San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript viii b 3. Although compiled as late as 1614, the volume contains descriptions of partly much older customs, for example the many processions in the streets of the town in choirboys were singing. A compact survey of these processions and chants is offered in Gabrielli 2020, 15-23 at 22, online, https://musicadocta.unibo.it/article/view/11927.

[9] Boynton 2008, 37-48 at 47.

[10] Der „Liber ordinarius Brixinensis“, ed. Gionata Brusa, in: Cantus Network – semantisch erweiterte digitale Edition der Libri ordinarii der Metropole Salzburg, Wien/Graz 2019, online, <gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.brixen>, 128.

[11] Liber ordinarius Brixinensis, Festum innocentum [sic].

[12] See Mackenzie 2011.

[13] Noggler 1885, 16-18.

[14] Büchner 2019, 31.

[15] Strohm 1993, 294-296. For a definition, see Rudolf Flotzinger, Ansingen, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, founded by Rudolf Flotzinger, ed. Barbara Boisits, online, https://musiklexikon.ac.at/0xc1aa5576_0x0001f702 (2002).

[17] It is interesting to note that the customs of both the Boy Bishop and the “Ansingen” were analogous to the annual springtime feasts of the Roman schola cantorum of the first Christian centuries, particularly the cornomania (a feast of undoubtedly pagan origins, when the sacristans disguised themselves as bishops) and the laudes puerorum at Easter, sung by the students in the streets on Easter Saturday for eggs and other gifts. On the extra-liturgical songs of the schola cantorum see Dyer 2008, 19-36 at 22-23.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Obermair 2008, 65, no. 967.

[21] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187. The manuscript, formerly presumed lost, has been located by Hannes Obermair, who gave a first description of it in Obermair 2005.

[23] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187 (Obermair 2008), f. 122v.

[24] On the different types of students in Tyrolean schools of the period, see also Post 1993, 34-35.

[25] A polyphonic setting of the antiphon (which belongs to the Song of Songs) is extant in the manuscript fragment from Muri-Gries: » F. Schlaglicht: Das Bozner Fragment.

[27] Strohm 1993, 295; see also » A. Gesänge zu Weihnachten.

[30] The expression “für sich” is interpeted here as implying a “separate” action outside the liturgical context.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Giulia Gabrielli: “Children’s Processions in Tyrol”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich, <https://musical-life.net/kapitel/childrens-processions-tyrol> (2023)