Member of the Florentine piffari

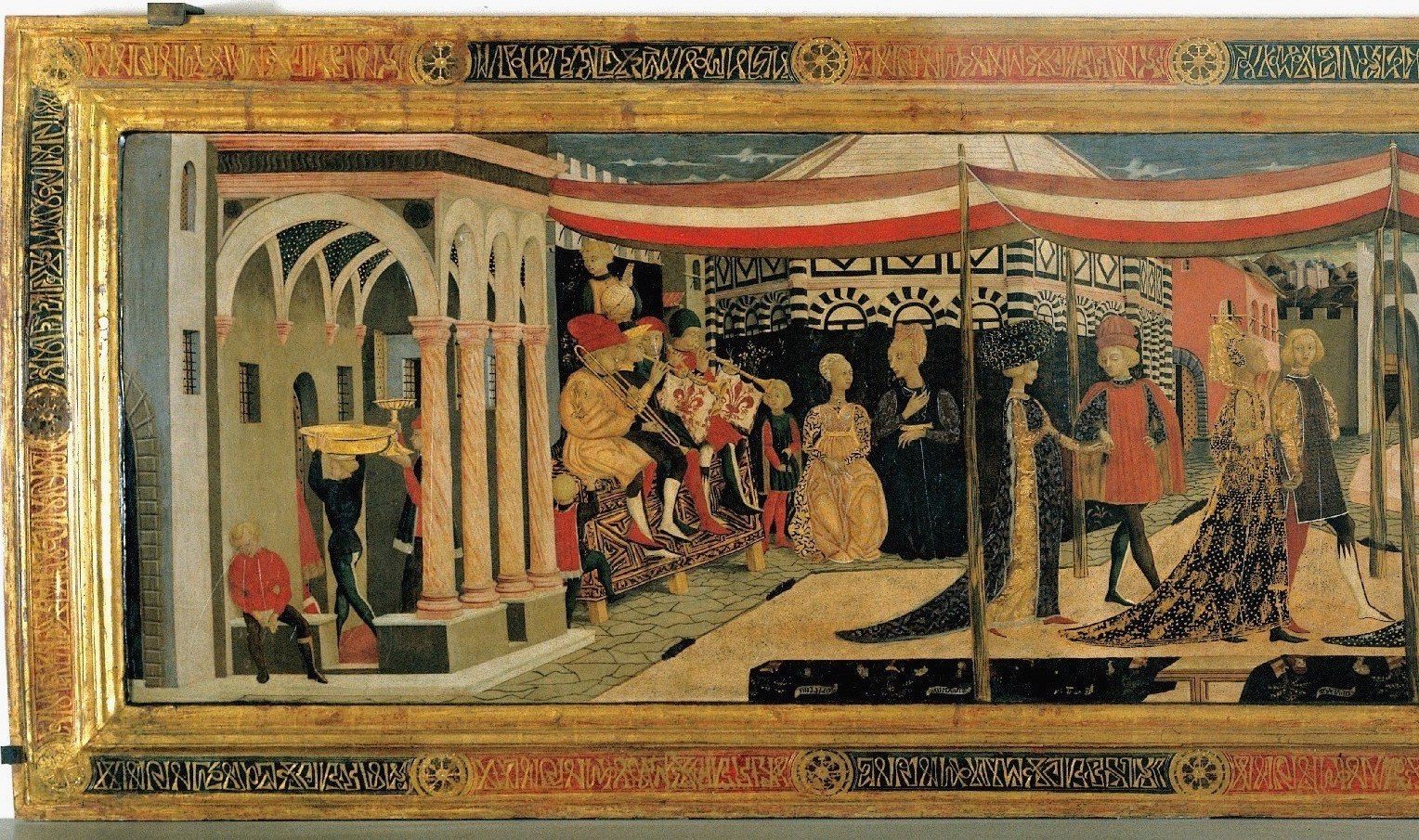

In 1489, Schubinger moved to Florence, one of the leading centres of instrumental music-making at the time.[21] The pivotal role in Florentine instrumental music was played by the piffari, an alta cappella ensemble, alongside two groups of trumpeters. Initially composed of three musicians, since 1443 the ensemble consisted of four musicians—three players of the soprano or alto shawm, and one trombonist.

Schubinger was hired in 1489 as the successor to the recently deceased trombonist Johannes di Johannes d’Alamania,[22] and thus held a position that was not only prestigious but also economically attractive. In addition to a comfortable base salary with various additional benefits, the Florentine piffari were offered the prospect of retirement benefits and the opportunity for additional income through private engagements, particularly from members of the Florentine nobility.[23]

The alta ensemble, combining shawms and a brass instrument with a slide mechanism, had become an established standard ensemble by 1450 across much of Europe, maintained by numerous cities and princes in Burgundy, the German-speaking regions, and Italy.[24] The widespread adoption of this ensemble type and its associated playing practices and repertoires was accompanied by increased transregional mobility of alta cappella players. A prominent phenomenon in the instrumental music scene of the fifteenth century was the significant presence of “German” instrumentalists in Italy. From the mid-century, musicians from “Alemania”[25] in the wind ensembles of Italian cities and courts played a leading role in their field. This phenomenon is sometimes compared in the secondary literature to the hegemony of Franco-Flemish singer-composers in the field of vocal polyphony.[26] Augustin Schubinger, his brothers Michel, who worked as a piffaro at the court in Ferrara from 1479 to 1519/20,[27] Ulrich the Younger, who was employed by the Gonzaga in Mantua from 1502 to 1519,[28] and Anthon, who also served the d’Este in Ferrara between 1506 and 1511,[29] thus represented a general condition, albeit in a particularly pronounced manner.

The trend towards recruiting German musicians can be clearly traced in Florence thanks to the abundant source material. As early as 1399, a “Niccolao Niccolai Teotonico” was employed there. In 1443, the piffaro ensemble was expanded to four players, all from the German-speaking region, specifically from Basel, Constance, Augsburg, and Cologne. That same year, the Signoria also decreed that henceforth only “forenses et alienigeni” (foreigners) should be appointed as piffari, probably referring to persons from north of the Alps.[30] While this stipulation was not consistently observed subsequently, the trombonists of the Florentine alta cappella were indeed always from the German-speaking area until the end of the fifteenth century.

[21] Cf. on the now well-documented instrumental music in Florence of the fifteenth century: Zippel 1892; Polk 1986; McGee 1999; McGee 2000; Polk 2000; McGee 2005; McGee 2008.

[22] McGee 2008, 185–186, 202.

[23] McGee 1999, 730–731; McGee 2000, 212–213.

[24] Cf. general literature on the alta cappella: Polk 1975; Welker 1983; Polk 1992a, 60–70, estimating that around 100 cities and 150 princes in the Holy Roman Empire employed an alta cappella (68); Tröster 2001; Neumeier 2015, especially 46–54. On practice in the Austrian region, see » E. Kap. Repräsentation und Unterhaltung; » I. Kap. Musica, Schalmeyen.

[25] The exact origin of musicians from “Alemania” is often not determinable. According to contemporary Italian usage, “Alemania” included the entire territory of the Holy Roman Empire, including regions like Flanders and Alsace. See Böninger 2006, 9–10.

[26] Cf. especially Polk 1994a.

[27] Lockwood 1984, 321–326; Lockwood 1985, 110 and 112, who also identified a son of Michel named Alberto (Albrecht), documented as a piffaro at the court of Ferrara in 1510/11 and 1517–1520.

[28] Ulrich is last documented in Mantua in October 1519; see Prizer 1981, 160. Contrary to the speculation that he may have remained in Mantua until 1522 (Polk 1989a, 502; Filocamo 2009, 235, note 17), it should be noted that Ulrich was employed by Archbishop Matthäus Lang in Salzburg in December 1519; see the service agreement (“Abred”) text in Hintermaier 1993, 38; see previously the note in Senn 1954, 21.

[29] Lockwood 1984, 190.

[30] McGee 1999, 732; McGee 2008, 162–163.

[1] A-Wn Cod. 2835 („Was in diesem püech geschriben ist, das hat kaiser Maximilian im xvc und xii Iar mir Marxen Treytzsaurwein seiner kay. Mt. secretarÿ müntlichen angeben.“), fol. 9r; Digital copy: https://digital.onb.ac.at/RepViewer/viewer.faces?doc=DTL_2985406&order=1…. Edition: Schestag 1883, 160.

[2] See Lütteken 2011, 174–181; Heidrich 2004, 58–63; » I. Instrumentalists at the Court of Maximilian I (Martin Kirnbauer).

[3] Initial insights into the biographies of the members of the Schubinger family are mainly owed to Keith Polk. See especially Polk 1989a (with numerous source references); Polk 1989b.

[4] See e.g., D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 55 (1457), fol. 112v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-03uw/1), vol. 56 (1458), fol. 120v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-0436/1), vol. 57 (1459), fol. 122v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-04cw/1).

[5] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 45 (1447), fol. 82r–82v (https://lod.academy/bmb/id/bmb-bm-06yu/1); cf. also Polk 1992a, 237.

[6] Generally on the institution of urban wind ensembles in late medieval Germany, see Polk 1987; Polk 1992a, 108–114; Green 2005; Green 2011; Neumeier 2015, 143–172; specifically on Augsburg, see Green 2012. These studies will be expanded here in » E. Musiker in der Stadt to cities of the Austrian Region.

[8] Polk 1989a, 498, note 1; Polk 1989b, 90, note 6; Polk 1987, 179.

[9] Moreover, the Augsburg accounting books from 1521 record a trumpeter named Jörg Schubinger in the service of Cardinal Matthäus Lang; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 115 (1521), fol. 32v (“Item i guldin Jorigen Schubinger des Bischoffs von Saltzburg trumetter”), see Birkendorf 1994, vol. 3, 247. Further details, particularly the family relationship to other Schubingers, about this musician are currently unknown.

[11] Polk 1989a, 495, speculates, with a view to the later careers of his sons, about a stay in Italy, which is not documented.

[12] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 70 (1477), fol. 92v.

[13] Green 2005, 22–23.

[14] D-Asa Ratsbücher, vol. 10 (1482–1484), fol. 124r; see Green 2005, 23.

[15] The entries in the Augsburg accounting books that record Schubinger as a town piper are: D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 74 (1481), fol. 64v; vol. 75 (1482), fol. 62v; vol. 76 (1483), fol. 53v; vol. 77 (1484), fol. 60r; vol. 78 (1485), fol. 52v; Ratsprotokolle vol. 10 (1484), fol. 124r; Baumeisterbücher, vol. 79 (1486), fol. 62r; vol. 80 (1487), fol. 65r. (The accounting books from the years 1478 to 1481 have not survived).

[16] For example, at the end of Maximilian I’s reign, the trumpet corps included Ludwig (Lutz) Mayer (Mair) and his sons Georg (Jurig) and Christoph. See the court personnel list of 1519 in Fellner/Kretschmayr 1907, 141, as well as Senn 1954, 20 and 22; Wessely 1956, 104–106. On Vienna musician families, see » E. Instrumentalisten und ihre Kunden. Cf. also the detailed reconstruction of family relationships within the urban instrumental ensembles of Florence in McGee 1999, 732–736.

[17] Schubinger, whose annual salary (totaling 36 fl.) was paid in four tranches on Ember Days, received his last payment on March 31, 1487, proportionally for the three-week period between Ember Day before Reminiscere (March 7) and the end of the month; see D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 80 [1487], fol. 65r: “Augustin Schubinger busauner […] Rt. ij v ß für 3 wochen antzal der quattember vnd ist daruff abgeschiden zu vnnserm Herren dem Ro. Kaÿser vnd vff seiner Kayserlichen gnaden schreiben seins dinsts erlassen. Samstag vor Iudica [March 31].” In 1488, Schubinger is already documented as “Emperor’s Trombonist” in the Augsburg accounting books, under the category “varende levte” where payments to outsiders were recorded; see Baumeisterbücher, vol. 81 [1488], fol. 16r: “Item ij fl Augustin kayserlicher busaner Samstag vor Reminiscere.” Polk 1989a, 501, mistakenly refers to “Emperor” as Maximilian I, who was not crowned Roman-German Emperor until 1508.

[18] Among others, D-Asa Steuerbuch 1504, fol. 17v (category d); Baumeisterbücher, vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v; vol. 97 (1503), fol. 28v. The identity of this “Augustin pfeiffer” with Schubinger is shown in the following entry concerning Schubinger’s wife in the tax book 1509, fol. 16r (category a): “magdalena schubingerin Augustein pfeiffers weib”.

[19] See Wessely 1958, 94; McDonald 2021, 177–178; » I. The court chapel of Maximilian I. (Grantley McDonald), Kap. Finances.

[20] Wessely 1958, 174, according to: Finance and Court Treasury Archives Vienna, Lower Austrian Treasury, files 14, no. 113.

[21] Cf. on the now well-documented instrumental music in Florence of the fifteenth century: Zippel 1892; Polk 1986; McGee 1999; McGee 2000; Polk 2000; McGee 2005; McGee 2008.

[22] McGee 2008, 185–186, 202.

[23] McGee 1999, 730–731; McGee 2000, 212–213.

[24] Cf. general literature on the alta cappella: Polk 1975; Welker 1983; Polk 1992a, 60–70, estimating that around 100 cities and 150 princes in the Holy Roman Empire employed an alta cappella (68); Tröster 2001; Neumeier 2015, especially 46–54. On practice in the Austrian region, see » E. Kap. Repräsentation und Unterhaltung; » I. Kap. Musica, Schalmeyen.

[25] The exact origin of musicians from “Alemania” is often not determinable. According to contemporary Italian usage, “Alemania” included the entire territory of the Holy Roman Empire, including regions like Flanders and Alsace. See Böninger 2006, 9–10.

[26] Cf. especially Polk 1994a.

[27] Lockwood 1984, 321–326; Lockwood 1985, 110 and 112, who also identified a son of Michel named Alberto (Albrecht), documented as a piffaro at the court of Ferrara in 1510/11 and 1517–1520.

[28] Ulrich is last documented in Mantua in October 1519; see Prizer 1981, 160. Contrary to the speculation that he may have remained in Mantua until 1522 (Polk 1989a, 502; Filocamo 2009, 235, note 17), it should be noted that Ulrich was employed by Archbishop Matthäus Lang in Salzburg in December 1519; see the service agreement (“Abred”) text in Hintermaier 1993, 38; see previously the note in Senn 1954, 21.

[29] Lockwood 1984, 190.

[30] McGee 1999, 732; McGee 2008, 162–163.

[31] D’Accone 1993; Zavanello 2005, 35–45.

[32] McGee 1999, 740–743; see also McGee 2005, 145–149; McGee 2008, 178–189.

[33] See the letter from Bartolomeo Tromboncino to Lorenzo de’ Medici dated June 10, 1489; edited in: Becherini 1941, 108–109.

[34] Letter from Michel Schubinger to Lorenzo de’ Medici dated June 7, 1489, in: Becherini 1941, 107–108. See also McGee 2008, 185–186. The stay in Milan may have been related to the wedding of Gian Galeazzo Maria Sforza and Isabella of Aragon on February 2. Details are unknown. It is certain, however, that Schubinger was not in the entourage of Friedrich III, who was in the Netherlands at that time.

[35] This document was first highlighted by Böninger 2006, 127. An in-depth analysis of the historical implications can be found in Schwindt/Zanovello 2019.

[36] About Cornelio di Lorenzo: D’Accone 1961, 334, 337, and 341–343.

[37] Schwindt/Zanovello 2019. See also Schwindt 2018c, 259–260.

[39] D-Asa, Baumeisterbücher, vol. 89 (1495), fol. 17r: “Augustin Schubinger der K Mt Trumbetter.” Senn 1954, 21, mentions (but without further source reference) an “apparently temporary” presence of Schubinger in Innsbruck in 1493.

[40] A 1495/96 payment by the city of Basel to “des romischen konigs zinken bloser” may also refer to Schubinger. See Ernst 1945, 222; Polk 1989b, 88.

[41] Wiesflecker 1971–1986, vol. 2, 255–256; Schwindt 2018c, 94–95.

[42] Payment record January 1497, F-Lad B 2159, fol. 178r–178v.

[43] Haggh 1988, 219; Polk 1992b, 88.

[44] Appointment document March 10, 1497, F-Lad B 2160, No. 71187. My heartfelt thanks to Grantley McDonald for bringing this and the document mentioned in note 43 to my attention.

[45] Bessey et al (Eds.) 2019, 192.

[46] Bessey et al. (Eds.) 2019, 23–24. I thank Werner Paravicini for relevant information (email, February 4, 2022).

[48] Unless otherwise mentioned, the information about Maximilian’s whereabouts here and in the following is based on Regesta Imperii XIV (online: http://www.regesta-imperii.de/regesten/baende.html), Stälin 1860 sowie Kraus 1899.

[49] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 93 (1499), fol. 22v. The payment note concerning Schubinger is not dated, but the preceding and following notes are, respectively, “Samstag vor katharina,” i.e., November 24, and “Samstag post lucie,” i.e., December 15.

[50] Wessely 1956, 115.

[51] RI XIV,3,1 n. 9792, in: Regesta Imperii Online, http://www.regesta-imperii.de/id/1500-01-30_4_0_14_3_1_814_9792. See the text of the letter in: Bertolotti 1890, 25. Based on this letter, the literature sometimes claims that Schubinger was in Mantua in January 1500; see Polk 1989a, 502; Filocamo 2009, 238. According to Filocamo, Schubinger is also mentioned in the spring of 1505 in the correspondence between Isabella and Alfonso d’Este. This possibly forms the basis of Polk 1989a, 501, unsubstantiated statement that Schubinger was active in Mantua in 1505. Definitive clarification will only be possible after an autopsy of the letters, which has yet to be undertaken.

[52] Wessely 1956, 116; Luger 2020, 118 and 136.

[53] Wessely 1956, 101–102.

[54] Schubinger, Jobst, and Jörg Nagel, as well as Jörg Holland, also received a payment from the city; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 99 (1505), fol. 27v–28; see Polk 1992b, 86.

[55] As suspected by Kelber 2018, 48, note 90.

[56] In: Hegel (Ed.) 1894, 83. See also Kelber 2018, 115.

[57] Schweiger 1931/32, 367.

[58] Straeten 1885, 172.

[59] Further payments from the Burgundian court to Schubinger are documented in: F-LadB B 2173 (Registres de comptes de la recette générale des finances 1501), fol. 73r–v; B 2180 (1502), fol. 154r and 186r (see van Doorslaer 1934, 39, and 163); B 2191 (1505), fol. 318r (see Fiala 2002, 379).

[60] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41281 (Stadsrekeningen Mechelen 1500/1501), fol. 192v: Payment to “Meester Augustyn diener ons genedige Herrn Hertoge Phillips van dat hij op ons liever vrouwen lichtmes dach speelde te hoogmissen In Sinte Rombouts kerke.” See also Polk 2005a, 65

[61] Gachard (Ed.) 1876, 178 and 287. See also Straeten 1885 1885, 158, and Polk 1989a, 501, who mistakenly identify Lausanne instead of Bourg-en-Bresse as the location of the Easter 1503 service.

[62] See van Doorslaer 1934, 51; Straeten 1885, 162–165; Pietzsch 1963, 746; Haggh 1980, 172–176; Ferer 2012, 33.

[63] Bessey et al. (Eds.) 2019, 350 and 355.

[64] It is also possible that Schubinger was the “des Ro. Ko zincken plaser” (imperial cornett player) documented in Nuremberg in 1506. See D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 407v: “Item i gulden des Ro. Ko zincken plaser”.

[65] Cf. Schwindt Schwindt 2018c, especially 53–56.

[66] Stadtarchiv Nördlingen, Stadtkammerrechnungen 1507, fol. 60v: “Augustain Zinkenblasser Kl. Mayt. busawnner verert selbannd auff aftermontag nach sanct vallentainstag [19. Februar]”; D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 101 (1507), fol 24r: “Samstag nach Letare [20. März]. […] Item ij guldin Augustin Kö mayt Busaner.” Also in 1507 is a likely reference to Schubinger, though not precisely dated, in: D-Nsa Reichsstadt Nürnberg, Losungsamt, Stadtrechnungen 181, fol. 426v: “Item i gulden der Romischen Kaiserlichen mt zinckenplaser.”

[67] See the detailed references in Kelber 2018 LIT, 58–59, 142; Grassl 2019, 239.

[68] Cf. the comprehensive account of this partly immensely agile and stimulating, partly quiet and productive period of music in Maximilian’s orbit in Schwindt 2018c, 188–194.

[69] Schuler 1995, 13–14 and 18–19.

[70] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 51 (word and page identical in vol. 52), fol. 239r: “Augustin schubinger pausauner geben / am xxij tag november zu seiner / außlosung hier, laut seiner quittung / iij gulden”.

[71] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41287 (Stads Rekeningen Mecheln 1507/1508), fol. 211r.

[73] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 58 (1512), fol. 299v (identical wording in vol. 59, fol. 139r–v): “Augustin Busaner x gulden an seinem Lifergelt.”

[74] See references in Grassl 2019, 241.

[75] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41291 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen, 1. Nov. 1511–31. Oct. 1512), fol. 209v.

[76] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 106 (1512), fol. 30v: “Samstag post katherine [27 November] / Item ij gulden dem Augustein pfeiffer Kay mt diener.”

[77] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 101 (1507), fol. 24r: “Samstag nach Letare [20 March]. […] / Item ij guldin Augustin Kö mayt Busaner”; vol. 103 (1509), fol. 24r: “Samstag post Cantate [12 May]. / Item ij guldin dem Augustein Kay mayt Busaner”; vol. 106 (1512), fol. 30v: “Samstag post Katherine [27 November] / Item ij gulden dem Augustein pfeiffer Kay mt diener”; vol. 108 (1514), fol. 26r: “Samstag nach Egidy [2 September] / Item ij guldin Augustein Busaner Kay mayt diener”; vol. 111 (1517), fol. 30r: “Samstag nach Egidij [5 September] / Item iiij guldin vlrichen vnd Augustein von augsburg busanern”; vol. 112 (1518), fol. 31r: “Samstag Leonhardj [6 November] / Item ij guldin augustein von Augsburg Kay mt. busaner.”

[78] Schwindt 2018c, 202–207.

[79] This is evident from the form of Schubinger’s entry in the Augsburg tax books, which lacks the designation typical for foreigners or non-citizens. For a detailed discussion of these sources and the Augsburg tax system of the late Middle Ages and Early Modern period: Clasen 1976 LIT; Krug 2006.

[80] D-Asa Steuerbücher 1495, fol. 14v (category c); 1501: fol. 18v (category d); 1505, fol. 17v; 1507, fol. 15r; 1508, fol. 15v (category c); 1509, fol. 16r (category a).

[81] Clasen 1976, 17–18.

[82] The claim that Schubinger was the owner of a house at Rossmarkt (so Busch-Salmen 1992, 65), cannot be verified based on the tax books.

[83] The Augsburg tax books from 1521 and 1522 mention a “Magdalena Schubingerin” with a tax payment; D-Asa tax books 1521, fol. 18v (category d), 1522, fol. 18r (category b). This person was likely not Schubinger’s wife (but perhaps his unmarried daughter?), because wives were usually recorded with their husband’s surname preceded by their first name and followed by the suffix “in” or with a reference to their marital status (e.g., in 1509, Schubinger’s wife: “magdalena schubingerin Augstein pfeiffers weib”). See Clasen 1976, 19.

[84] For Hofhaimer’s tax exemption, which was not fully accepted by the city authorities, see Nedden 1932/1933, 28–29; Schuler 1995.

[85] Böhm 1998, 166–168.

[86] Schwindt 2018c, 202–203; Schwindt 2020, 63–64; Birkendorf 1994, vol. 3, 243. For municipal expenses for performances by instrumentalists, see also » E. Städtisches Musikleben.

[87] A-Whh Reichskanzlei, Reichsregisterbücher QQ (Maximilian I.: Reichs- und Hauskanzleiregistraturbuch 1514), fol. 36v–37r; online: https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=1274877&DEID=10&S….

[88] For Steudl, see Schwindt 2018a, 2–4.

[89] Appointment document: A-Whh Reichskanzlei, Reichsregisterbücher QQ (Maximilian I.: Reichs- und Hauskanzleiregistraturbuch 1514), fol. 36r–36v; service contract: A-Whh Urkundenreihe, Familienurkunden 969. For other examples of (often three-year) appointments, see RI XIV,2 n. 7032; RI XIV,3,1 n. 11552; RI XIV,3,2 n. 10718, n. 14172; RI XIV,4,1 n. 16514, n. 16810; Kostenzer 1970, 80, 82, 88 and 93; see also Gänser 1976, 30 and 185.

[90] See generally Zolger 1917, 43; Gänser 1976, 47–50; Noflatscher 2017, 425–426.

[91] Schwindt 2018a, 3; Schwindt 2018c, 53.

[92] As with the treasurer Jacob Villinger, who according to his appointment letter from 1512 was entitled to horses. See Fellner/Kretschmayr 1907, 51 and 142.

[93] See examples in Wessely 1958, 408, 410; Pass 1980, 350, 354, and 392; Grassl 2011, 120–121 and 129. For the case of the “geyger” Caspar Egker, who is listed under “Annder Officir” in the directory of Maximilian’s remaining court staff from 1520, see Koczirz 1930/1931, 531–532. For this period, see » I. Kap. Ferdinands und Annas Zink-Posaunen-Ensemble.

[94] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher, vol. 113 (1519), fol. 30r: “am hailigen pfingstabent [12 June] / Item ij gulden Augstein Schubinger Kay mayt hochloblicher gedachtnis Busaner gewesen ist”; vol. 114 (1520), fol. 32r: “Samstag nach Letare [24 March] / Item ij guldin Augustein Schubinger weyland Kay trumeter”; vol. 115 (1520), fol. 32v: “Samstag post Johannes Baptiste [29 June] / Item ij gulden Augustein Schübingern Kay mayt. busaner”; vol. 116 (1522), fol. 35v: “Samstag post Udalricj [5 July] / Item ij guldin. Augustein Schubinger Kay. mt busawner”.

[95] See Schwindt 2018a, 14; Schwindt 2018c, 207; Bente 1968, 293–294.

[96] B-Baeb Algemeen Rijksarchief / Archives générales du Royaume, V132–41298 (Stads Rekeningen Mechelen, 1. Nov. 1519–31. Okt. 1520), fol. 232v. For the meaning of “thuereken” as cornett, see Polk 1992b, 88, who cites the reference not in connection with Ferdinand, but with “musicians in the retinue of Maximilian I.” Historians have also overlooked the Mechelen city accounts as a source for reconstructing Ferdinand’s court during his time in the Netherlands; see Castrillo-Benito 1979, 426–427; Rill 2003, 37–46.

[97] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 73 (1524), fol. 194v; vol. 74 (1525), fol. 157v; vol. 75 (1526), fol. 147v (1527 missing); vol. 76 (1528), fol. 140v; vol. 77 (1529), fol. 167v; vol. 78 (1530), fol. 178r–v; vol. 79 (1531), fol. 170r–171r.

[99] Payments ranged from 1524 to 1529 between four and 13 gulden; only in 1530 and 1531 did the Innsbruck Treasury allocate 89 and 48 gulden, 31 kreuzers, and three vierers (partly not in cash but by covering clothing costs), but even then, the total amount due over the years was far from reached.

[100] Once again without an amount specified; D-Asa tax book 1528, fol. 23v (category c); tax book 1529, fol. 23r (category b).

[101] D-Asa Baumeisterbücher vol. 121 (1527), fol. 36r: “Samstag nach trinitatis / Item ij fl. Augustein Schubinger k. mt. pusauner”; vol. 122 (1528), fol. 36v: “Samstag nach margrethe / Item ij fl augustein schubinger verert”; vol. 124 (1530), fol. 35r: “Samstag nach Reminiscere / Item ij guldin Augustein Schubinger”; vol. 125 (1531), fol. 36r: “Uff 5. Januarij / Item ij gulden Augustein Schubinger”.

[103] A-Ila Oberösterreichische Kammer, Raitbücher vol. 73 (1524), fol. 194v.