Ansingen itineraries at Christmas time

The following chapter of the regulation (» E. Kap. Das Urbar der Bozner Pfarrkirche) is entirely concerned with the great Ansingen processions at Christmas time, which took place in the town and in the near mountains on the four days following Christmas, namely St Stephen’s Day (26 December), St John the Evangelist’s Day (27 December), Holy Innocents’ Day (28 December) and St Thomas’s Day (29 December). The title of this chapter is as follows (f. 135r):

Hye ein vermerchkt die ordnung, die man mit ansingen auf Vns(er) lieben frawn werch zu den weyhennachtt(e)n in der Stat und ausserthalb(e)n gehaltt(e)n hat mitt erb(er)n pawleutten, als von alter gewonhait ist.

(Here is recorded the regulation which has been observed with Ansingen by the church fabric of Our Lady’s at Christmas in the town and outside, with honorable house-owners, as is ancient custom.)

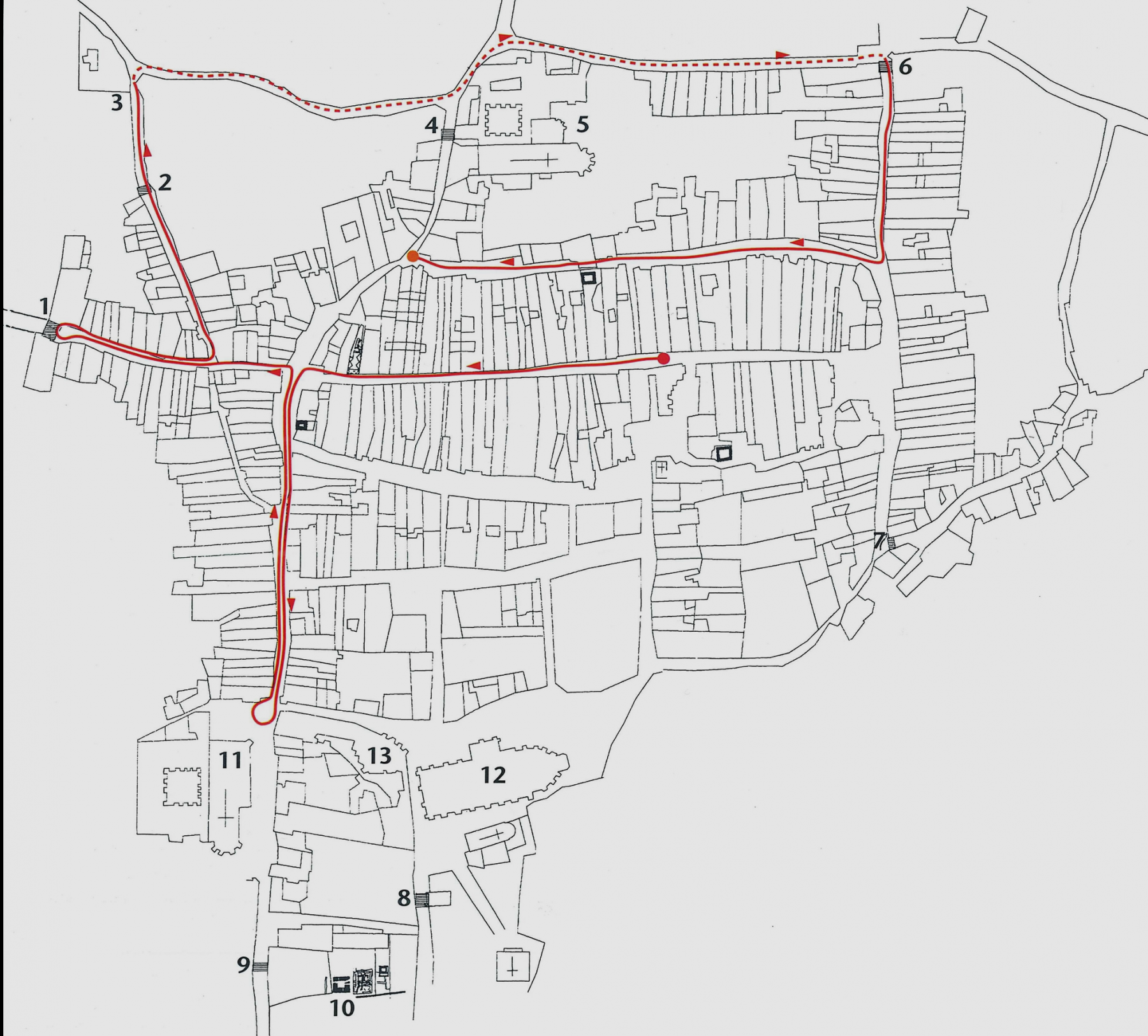

The ensuing text is a document of outstanding historical value for its wealth of information and descriptive accuracy, unparalleled in Tyrol. It identifies, in fact, the circuits, the streets and the names of the houses in front of which the singers had to stop and perform during their processions in the days after Christmas. The description provides a physical and musical map of the fifteenth-century town and at the same time opens up a sketch of contemporary society. Michela Paoli-Poda has transcribed the regulation and aimed to reconstruct the itineraries of the first three days, with the help of old town maps.[26] » Fig. Ansingen itinerary 27 December and » Fig. Ansingen itinerary 28 December present the maps of the second and third days; we give in the appendix a new transcription of the original narrative. Although the original text contains some passages that are difficult to interpret today – the topographical references differ from the present ones, and indeed the town has changed much – it allows us to follow the Ansingen procession virtually, helped by the modern street names.

On the first day (St Stephen’s Day, 26 December) the procession began after the Vespers service. It went first through the commercial centre of the town, along the present Via dei Portici (Laubengasse). Starting from Piazza Erbe (Obstplatz), the procession went eastwards through almost the entire street towards Piazza Municipio (Rathausplatz), coming to a halt near the New Chapel (at the height of Piazza del Grano, Kornplatz) and returning in the parallel street.

On the second day (St John’s Day) the singing procession began already after High Mass (Fronambt).

The itinerary was definitely longer and more challenging. The map shows something like a star-shaped itinerary, which had its centre at Piazza Erbe. From here, the first excursion wenth south, through the Schustergasse (now Goethestrasse) towards the Piazza dei Domenicani (Dominikanerplatz), reversed there and returned to Piazza Erbe through the parallel street. Then the procession went east until the eastern towngate (Hurlachtor) and back, but before re-entering Piazza Erbe, a smaller group of singers, probably two or three, was directed towards the St Martin’s brook (which then provided the town with fresh water), while the remaining group went towards the Franciscan monastery. At this point the description becomes somewhat unclear, so that the itinerary of the singers cannot be reconstructed precisely, but it moved in the area of the Parfusser (Franciscans) to terminate in the Obern Graben (today’s Via Streiter).

On the third day (Holy Innocents Day) the singers began after High Mass and, as on the previous day, their itinerary was very long.

The starting point was the Wangergasse (same name as today) near Porta Vintler (Vintlertor), thus not far from the place where the procession of the previous day had ended. From here, it went south along the Via Bottai (Bindergasse), and in a large curve towards west, it arrived at the parish church (cathedral today). From there, the procession continued towards the southern town gate, until the bridge over the Eisack/Isarco river, to return to the parish church the same way. Afterwards the singing continued in the new town and the Unterer Graben (south-west of the centre); on the same day a separate action after vespers was the Ansingen in the parish house and in the Holy Ghost hospital.

This is how the Ansingen was carried out within the town. In fact, for the fourth day (St Thomas of Canterbury, 29 December) the regulation ordered the children to go singing in the mountains (f. 135v), perhaps in Jenesien or on the Ritten, as was the old custom, but states that no church warden ever accompanied them:

It(e)m an dem vierd(e)n tag so gennd dy ansing(er)n an das gepirg, als von alter herchome(n) ist, do get kain kirchpräbst nicht mitt etc.

[26] Michela Paoli-Poda, Suoni e musica a Bolzano nel XV secolo, 43-48. For Mathäus Merian’s map of 1645, see » Fig. Panorama Bozen.

[1] For a compact history of Tyrolean schools, see Augschöll-Blasbichler, 2019, 96-106 at 96-101, online, https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/qdi/article/view/2643 (April 2023). On music in the schools, see Post 1993; Herrmann-Schneider 2023, online ,https://musikgeschichten.musikland-tirol.at/content/musikintirol/musikinkloesternusw/musik-in-pfarrkirchen.html (April 2023).

[2] Cfr. Büchner 2019, 16-49 (Teil I); 94/1, 2020, 46-72 (Teil II); 94/2, 2020, 20-61 (Teil III); 94/3, 2020, 40-61 (Teil IV); 94/4, 2020, 28-71 (Teil V): in Teil I, 27, a few examples from Tyrolean schools are given.

[3] As underlined by Hannes Obermair, referring to the parish church of Gries near Bolzano, the “System Church” represents in the 15th century an “efficient mixture of cult, community, identity and economical sphere“: see Obermair 2012, 137-174 at 137.

[4] Büchner 2019, 27-28.

[5] Preserved at San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript vii a 10s. Transcribed by Gionata Brusa, online, Cantus Network. Libri ordinarii of the Salzburg metropolitan province, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:cantus .

[6] Modern edition in Hofmeister-Winter 2001. This regulation of the sixteenth century informs about various processions with the participation of children, and about the ancient, widely-known custom of “Kindelwiegen” (child-rocking) which at Bressanone was reserved for the masters and students of the cathedraL school: see » A. Kap. Kindelwiegen.

[7] San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript viii b 3. Although compiled as late as 1614, the volume contains descriptions of partly much older customs, for example the many processions in the streets of the town in choirboys were singing. A compact survey of these processions and chants is offered in Gabrielli 2020, 15-23 at 22, online, https://musicadocta.unibo.it/article/view/11927.

[9] Boynton 2008, 37-48 at 47.

[10] Der „Liber ordinarius Brixinensis“, ed. Gionata Brusa, in: Cantus Network – semantisch erweiterte digitale Edition der Libri ordinarii der Metropole Salzburg, Wien/Graz 2019, online, <gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.brixen>, 128.

[11] Liber ordinarius Brixinensis, Festum innocentum [sic].

[12] See Mackenzie 2011.

[13] Noggler 1885, 16-18.

[14] Büchner 2019, 31.

[15] Strohm 1993, 294-296. For a definition, see Rudolf Flotzinger, Ansingen, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, founded by Rudolf Flotzinger, ed. Barbara Boisits, online, https://musiklexikon.ac.at/0xc1aa5576_0x0001f702 (2002).

[17] It is interesting to note that the customs of both the Boy Bishop and the “Ansingen” were analogous to the annual springtime feasts of the Roman schola cantorum of the first Christian centuries, particularly the cornomania (a feast of undoubtedly pagan origins, when the sacristans disguised themselves as bishops) and the laudes puerorum at Easter, sung by the students in the streets on Easter Saturday for eggs and other gifts. On the extra-liturgical songs of the schola cantorum see Dyer 2008, 19-36 at 22-23.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Obermair 2008, 65, no. 967.

[21] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187. The manuscript, formerly presumed lost, has been located by Hannes Obermair, who gave a first description of it in Obermair 2005.

[23] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187 (Obermair 2008), f. 122v.

[24] On the different types of students in Tyrolean schools of the period, see also Post 1993, 34-35.

[25] A polyphonic setting of the antiphon (which belongs to the Song of Songs) is extant in the manuscript fragment from Muri-Gries: » F. Schlaglicht: Das Bozner Fragment.

[27] Strohm 1993, 295; see also » A. Gesänge zu Weihnachten.

[30] The expression “für sich” is interpeted here as implying a “separate” action outside the liturgical context.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Giulia Gabrielli: „Children’s Processions in Tyrol“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich, <https://musical-life.net/kapitel/childrens-processions-tyrol> (2023)