Parish schools and communities

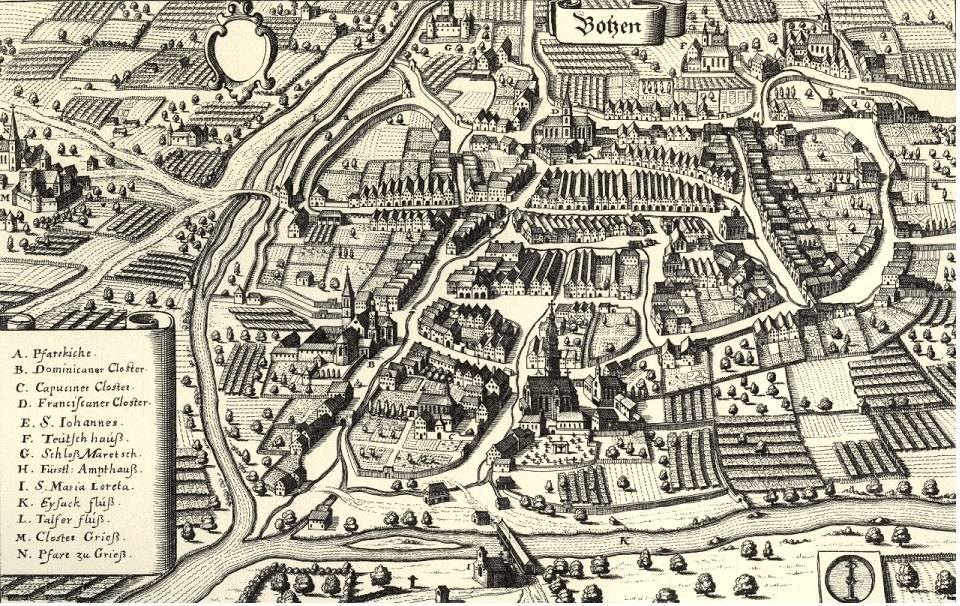

If we were present in a Tyrolean town in the fifteenth century, what we would hear most of the time would be the voices of children. Games, running, laughter, noises certainly filled the streets of the populated town centres, but children’s songs also played an important part in the life of the urban community. In fact, historical sources concerning Tyrol tell of numerous occasions of collective singing in public places, performed by the local schoolschildren. All education still took place in church schools: in the cathedral school of Brixen/Bressanone and in the many parish schools distributed in the area. The latter are documented in Tyrol since the thirteenth century;[1] they operated both within the largest towns such as Bozen/Bolzano, Merano, Innsbruck, Hall in Tyrol, and in many smaller centres.

The parish schools, which had been founded to educate young clerics, were increasingly influenced by the civic authorities and became, in fact, communal schools.[2] It is worth remembering in this context that the parish churches of late-medieval Tyrol functioned not only as religious centres, but also mirrored the social and economical identities of the civic and ecclesiastical communities that they represented.[3] It is thus no surprise that the musical activities of such a school, including its processions, were strongly conditioned by this interaction between civic and ecclesiastical powers. One example was the parish school of Bolzano, which in the fifteenth century was particularly active in music (» E. Bozen/Bolzano: Musik im Umkreis der Kirche). The rich documentation available today shows how the urban community organised, supervised and funded the local church school of St Mary’s (» E. Kap. Das Salve regina des Rats). The town authorities themselves exerted massive influence on the parish school; an example of this is the imposition, in 1479, of scholasticus (schoolmaster) Augustin Ayrinsmaltz on the Bolzano school by Duke Siegmund of Austria, Count of Tyrol. This nomination caused great dissatisfaction within the ecclesiastic and civic community of Bolzano and triggered a long, contentious quarrel between the schoolmaster, the town and the duke.[4] The maestro was in fact completely incompetent in music, so that according to the community he was quite unable to cover the task of schoolmaster.

[1] For a compact history of Tyrolean schools, see Augschöll-Blasbichler, 2019, 96-106 at 96-101, online, https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/qdi/article/view/2643 (April 2023). On music in the schools, see Post 1993; Herrmann-Schneider 2023, online ,https://musikgeschichten.musikland-tirol.at/content/musikintirol/musikinkloesternusw/musik-in-pfarrkirchen.html (April 2023).

[2] Cfr. Büchner 2019, 16-49 (Teil I); 94/1, 2020, 46-72 (Teil II); 94/2, 2020, 20-61 (Teil III); 94/3, 2020, 40-61 (Teil IV); 94/4, 2020, 28-71 (Teil V): in Teil I, 27, a few examples from Tyrolean schools are given.

[3] As underlined by Hannes Obermair, referring to the parish church of Gries near Bolzano, the “System Church” represents in the 15th century an “efficient mixture of cult, community, identity and economical sphere“: see Obermair 2012, 137-174 at 137.

[4] Büchner 2019, 27-28.

[1] For a compact history of Tyrolean schools, see Augschöll-Blasbichler, 2019, 96-106 at 96-101, online, https://cab.unime.it/journals/index.php/qdi/article/view/2643 (April 2023). On music in the schools, see Post 1993; Herrmann-Schneider 2023, online ,https://musikgeschichten.musikland-tirol.at/content/musikintirol/musikinkloesternusw/musik-in-pfarrkirchen.html (April 2023).

[2] Cfr. Büchner 2019, 16-49 (Teil I); 94/1, 2020, 46-72 (Teil II); 94/2, 2020, 20-61 (Teil III); 94/3, 2020, 40-61 (Teil IV); 94/4, 2020, 28-71 (Teil V): in Teil I, 27, a few examples from Tyrolean schools are given.

[3] As underlined by Hannes Obermair, referring to the parish church of Gries near Bolzano, the “System Church” represents in the 15th century an “efficient mixture of cult, community, identity and economical sphere“: see Obermair 2012, 137-174 at 137.

[4] Büchner 2019, 27-28.

[5] Preserved at San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript vii a 10s. Transcribed by Gionata Brusa, online, Cantus Network. Libri ordinarii of the Salzburg metropolitan province, https://gams.uni-graz.at/context:cantus .

[6] Modern edition in Hofmeister-Winter 2001. This regulation of the sixteenth century informs about various processions with the participation of children, and about the ancient, widely-known custom of “Kindelwiegen” (child-rocking) which at Bressanone was reserved for the masters and students of the cathedraL school: see » A. Kap. Kindelwiegen.

[7] San Candido/Innichen, Collegiate Foundation, manuscript viii b 3. Although compiled as late as 1614, the volume contains descriptions of partly much older customs, for example the many processions in the streets of the town in choirboys were singing. A compact survey of these processions and chants is offered in Gabrielli 2020, 15-23 at 22, online, https://musicadocta.unibo.it/article/view/11927.

[9] Boynton 2008, 37-48 at 47.

[10] Der „Liber ordinarius Brixinensis“, ed. Gionata Brusa, in: Cantus Network – semantisch erweiterte digitale Edition der Libri ordinarii der Metropole Salzburg, Wien/Graz 2019, online, <gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.brixen>, 128.

[11] Liber ordinarius Brixinensis, Festum innocentum [sic].

[12] See Mackenzie 2011.

[13] Noggler 1885, 16-18.

[14] Büchner 2019, 31.

[15] Strohm 1993, 294-296. For a definition, see Rudolf Flotzinger, Ansingen, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, founded by Rudolf Flotzinger, ed. Barbara Boisits, online, https://musiklexikon.ac.at/0xc1aa5576_0x0001f702 (2002).

[17] It is interesting to note that the customs of both the Boy Bishop and the “Ansingen” were analogous to the annual springtime feasts of the Roman schola cantorum of the first Christian centuries, particularly the cornomania (a feast of undoubtedly pagan origins, when the sacristans disguised themselves as bishops) and the laudes puerorum at Easter, sung by the students in the streets on Easter Saturday for eggs and other gifts. On the extra-liturgical songs of the schola cantorum see Dyer 2008, 19-36 at 22-23.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Obermair 2008, 65, no. 967.

[21] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187. The manuscript, formerly presumed lost, has been located by Hannes Obermair, who gave a first description of it in Obermair 2005.

[23] F-Sn Ms. allemands 187 (Obermair 2008), f. 122v.

[24] On the different types of students in Tyrolean schools of the period, see also Post 1993, 34-35.

[25] A polyphonic setting of the antiphon (which belongs to the Song of Songs) is extant in the manuscript fragment from Muri-Gries: » F. Schlaglicht: Das Bozner Fragment.

[27] Strohm 1993, 295; see also » A. Gesänge zu Weihnachten.

[30] The expression “für sich” is interpeted here as implying a “separate” action outside the liturgical context.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Giulia Gabrielli: „Children’s Processions in Tyrol“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich, <https://musical-life.net/kapitel/childrens-processions-tyrol> (2023)