Transcribing and reconstructing Oswald’s polyphonic songs

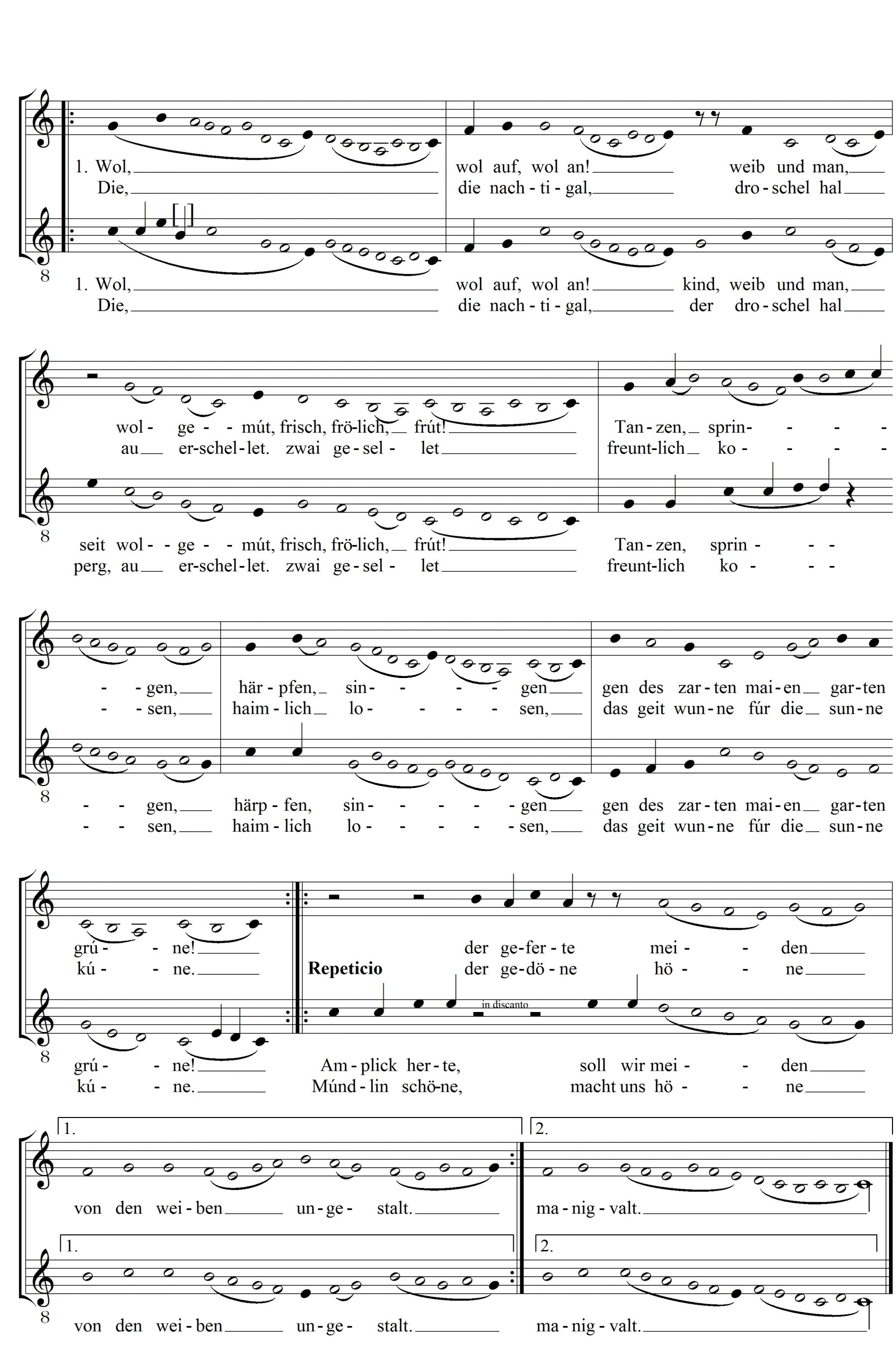

A note-against-note transcription is largely unproblematic for those songs which coordinate the two voices by simply counting the notes, such as Kl 51 and Kl 84, or even the melodically erratic Kl 37/38. However, those transmissions with a substantial amount of red notation and occasional bursts of diminutions do not only complicate an edition but also put significant obstacles in the way of reconstructing an intended performance practice. Previous editors have sought a definite rhythmical solution for these pieces and in doing so created versions which, instead of doing justice to the central non-mensural aspects of this repertory, went in the opposite direction by offering pointedly rhythmical editions to the extent of proposing irregular dance metres. I would suggest a new approach to the edition of these pieces, which leaves open certain aspects of their rhythm, and to add a commentary in which the rhythmic openness and fluidity required for a successful performance is discussed: a performance that is directed by the flow of the text and the modality of the melody rather than a prescribing mensural notation. An attempt in this direction can be seen in my edition of Kl 75 (» Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an).[19] For this song the scribe apparently used mensural note signs to show degrees of rhythmic fluidity in a melodic line: while black semibreves and minims represent the slow and fast ends of this spectrum, red semibreves take the middle ground. The orthodox meaning of red semibreves as a sesquialtera proportion in a major prolation is here used in an unorthodox way to indicate a minute rhythmic shift – usually an acceleration – instead of a precise rhythm.[20] This would also explain why in songs like Kl 75 red semibreves tend to occur in both voices simultaneously and in parallels.

Edition of Kl 75, Oswald von Wolkenstein, Wol auff, wol an (A-Wn Cod. 2777, fol. 35r). Black semibreves are represented as black note heads, black minims as quavers, and red semibreves as hollow (white) note heads; an online scan of the original notation can be found under the link http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/10048508.

The parallels, in turn, belong to the practice of fifthing. In Oswald’s songs, however, they do not only appear as parallel fifths, but also as parallel sixths with apparent equivalent meaning. It seems that Oswald had extended the concept of fifthing to include the interval of the sixth and employed both interchangeably. This equivalent use can be observed in Kl 51, Kl 75,[21] Kl 77, Kl 79 and Kl 84.

The notational intricacies that surround many of these pieces (especially the unorthodox use of red notation) as well as inaccuracies and mistakes regarding pitch and rhythm together with the lack of a control group of similar compositions posed a major obstacle for their edition and interpretation, so that – lacking an adequate edition and a proper ‘tool kit’ to deal with their specific features – these pieces were rarely performed or recorded in the modern age. Four songs make an exception: Kl 51, Kl 84, Kl 93, and Kl 101 actually have become some of the most popular Oswald songs today, mediated through early reference recordings of the early music revival.

[19] A recording of this edition, though experimentally transposed to a D-mode, can be found on the album The Cosmopolitan – Songs by Oswald von Wolkenstein. Ensemble Leones (Christophorus, 2014), track 9. Other examples for a new edition of Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony can be found in Lewon 2016a, ‘Ach senliches leiden (Kl 51)’, pp. 35–37, and ‘Des himels trone (Kl 37)’, pp. 38–43.

[20] For a first proposal of this interpretation, see Lewon 2011, pp. 168–191 at pp. 182–184.

[21] In » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an, most melismas are in parallel fifths; the cadential melisma over the word ‘springen’ and a section of the final melisma of the clos, however, run in parallel sixths.

[1] On these sacred repertories, see » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Grundlagen (Alexander Rausch), and » A. Klösterliche Mehrstimmigkeit: Arten und Kontexte (Reinhard Strohm).

[2] Pelnar 1978, and substantiated in Pelnar 1982, Textband.

[4] „WolkA“: A-Wn Cod. 2777 (?Vienna, c. 1425): „WolkB“: A-Iu o. Sign.

[5] See Lewon 2017, pp. 134–137.

[6] This assessment supports Pelnar’s statement (Pelnar 1982, Textband, p. 21) against a development from a more ‘primitive’ to a more ‘sophisticated’ counterpoint within Oswald’s œuvre: ‘Auf keinen Fall dürfen die Gruppen [‘bodenständig’ und ‘westlich’] chronologisch als Entwicklungsphasen aufgefaßt werden, wie es etwa Salmen bei seiner Datierung der Lieder macht’ (Under no circumstances should the categories [‘native’ and ‘Western’] be understood as chronological phases of a development, as Salmen did in his dating of the songs).

[7] Pelnar 1978, p. 275f.

[8] For a more comprehensive summary of the concept of ‘reference rhythm’, see Lewon 2012, 169–173.

[9] ‘Strichnotation’: see » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs and Glossary.

[10] The main manuscript for the songs of the Monk of Salzburg, the Mondsee-Wiener Liederhandschrift (A-Wn Cod. 2856), is one of the first musical manuscripts that makes a clear division between secular and sacred songs with the rubrics “werltlich” and “geistlich”; see März 1999, pp. 367–368.

[11] ‘Kl’ numbers refer to the numeration in the standard text edition, Klein 2015 (and earlier).

[12] ‘W’ (‘weltlich’) numbers refer to the numeration in März 1999.

[13] The rubric to W 8 (Ich klag dir, traut gesell) by the Monk confirms this practice ex negativo: “Ain tenor von hübscher melodey als sy ez gern gemacht haben darauf nicht yeglicher kund übersingen” (A tenor with a pretty melody, the way they liked to make them. Not everyone was capable of singing an upper voice to this). See also » B. Kap. Ich klag dir traut gesell (David Murray).

[14] Lewon 2011; see the table on pp. 189-191. Not all of the remaining songs listed there are proven contrafacta, but their notation and counterpoint strongly suggest a model from contemporary polyphonic exemplars. There is one more piece that could be added to the list of twelve below: Kl 21 (Ir alten weib), a monophonic song that appears to be a cognate to the Neidhart song Der sawer kübell - Niemand sol sein trauren tragen lange (see Mark Lewon, ‘Oswald quoting Neidhart: Ir alten weib (Kl 21) & Der sawer kübell (wl)’ (2014), accessible online at: https://mlewon.wordpress.com/2014/06/30/oswald-quoting-neidhart/). Michael Shields (2011) has suggested that the third section of this Oswald song could contain a piece of hidden polyphony in the form of a fuga. Should this prove true, then Kl 21 could be another case of non-mensural polyphony, employing reference rhythm. Since the claim is hard to substantiate and canons are excluded from the list – most of them being contrafacta – I will, for the time being, leave this song aside.

[15] In WolkA, only Kl 79 was notated separately a few pages later, probably because it was added with a second layer of repertory. For the scribal layers of the manuscript, see Delbono 1977. In WolkB, song Kl 37/38 was separated from the block and notated in a monophonic version in the first half of the manuscript, while the other four were grouped together.

[16] A-Iu o. Sign. (?Basel, c. 1432).

[17] See chapter 5.3 ‘Oswald quoting Oswald: Crossing the Border to Polyphony’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 260–268.

[18] For an in-depth analysis of the modal shifts of Kl 101 in the different sources, see chapter 5.1 ‘“Wach auff, mein hort”: A Melody of Modal Ambiguity’, in Lewon 2018, pp. 241–53.

[19] A recording of this edition, though experimentally transposed to a D-mode, can be found on the album The Cosmopolitan – Songs by Oswald von Wolkenstein. Ensemble Leones (Christophorus, 2014), track 9. Other examples for a new edition of Oswald’s non-mensural polyphony can be found in Lewon 2016a, ‘Ach senliches leiden (Kl 51)’, pp. 35–37, and ‘Des himels trone (Kl 37)’, pp. 38–43.

[20] For a first proposal of this interpretation, see Lewon 2011, pp. 168–191 at pp. 182–184.

[21] In » Notenbsp. Wol auff, wol an, most melismas are in parallel fifths; the cadential melisma over the word ‘springen’ and a section of the final melisma of the clos, however, run in parallel sixths.

[22] März 1999. See also » B. The secular songs of the Monk of Salzburg (David Murray). The secular songs (‘W’ for weltlich), are edited in März 1999, the sacred songs (‘G‘ for geistlich), in Waechter-Spechtler 2004.

[23] Rubric: “Der tenor ist der tischsegen” (This tenor is [called] the benediction).

[24] Rubric: “Der tenor haizt der freüdensal nach ainem Lusthaws pey Salzburg […]” (This tenor is called the house of pleasure after a hunting lodge near Salzburg […]).

[25] Rubric: see n. 13 above.

[26] For a more formal definition of monophonic ‘tenores’, see März 1999, pp. 11–2, 14–19, 31–3 and 36–40. An extended interpretation of the use and function of such ‘tenores’ by Reinhard Strohm and myself is given in Lewon 2018, pp. 225–226.

[27] In fact, Lorenz Welker argued that the motet-like song W54* is an example of extemporised counterpoint, which needed to be written because it carries a text. In other circumstances the discantus would not have been notated, but extemporised: see Welker 1984/1985, p. 55.

[28] Melody rubric: “Das nachthorn, vnd ist gut zu blasen” (The night horn, and it is suitable for wind instruments); second voice rubric: “Das ist der pumhart dar zu” (This is the accompanying bombarde).

[29] Melody rubric: “Das taghorn, auch gut zu blasen, vnd ist sein pumhart dy erst note vnd yr ünder octaua slecht hin.” (The day horn, also suitable for wind instruments, and its bombarde is simply the first note down an octave).

[30] See Welker 1984/1985.

[31] Rubric: “Das kchühorn […]” (The cow horn […]).

[32] Melody rubric: “Das haizt dy trumpet vnd ist auch gut zu blasen. Das swarcz is er, das rot ist sy” (This is called the trumpet and it is also suitable for wind instruments. The black [notation and text] is him, the red [notation and text] is her). Second voice rubric: ‘Das ist der wachter dar zu’ (This is the watchman for this).

[33] See März 1999, p. 368.

[34] On the musical types trumpetum and tuba (‘trompetta music’), see Strohm 1993, pp. 108-111 and passim.

[35] See » E. Kap. Hornwerke, where it is now suggested that a Hornwerk may have existed in the 15th century on the tower of the Salzburg parish church or of the town hall.

[36] März 1999, pp. 12 and 368.

[37] Both of them feature a dialogue of two lovers in their main melody, accompanied by a running commentary in the second voice.

[38] März 1999, p. 375.

[39] A recording is » Hörbsp. Untarnslaf - Das kchúhorn (Ensemble Leones), https://musical-life.net/audio/untarnslaf-das-kchuhorn (2015), where I refer to this song as a ‘pseudo-’ or ‘peasant-motet’.

[40] A stylised semiminima is used as the custos throughout the section with polyphonic songs and monophonic ‘tenores’.

[41] See Welker 1984/1985.