Musical endowments up to c. 1420

The design and musical development of liturgical services in Viennese churches can be understood through three groups of documents: foundation charters, administrative records (e.g. accounts) and service orders (libri ordinarii). The chronological orientation of these types of sources differs greatly: while foundation charters aim to determine the future for all eternity, administrative records reflect the changing circumstances from year to year; service orders attempt to codify what already claims established status and is intended to remain in force.[44]

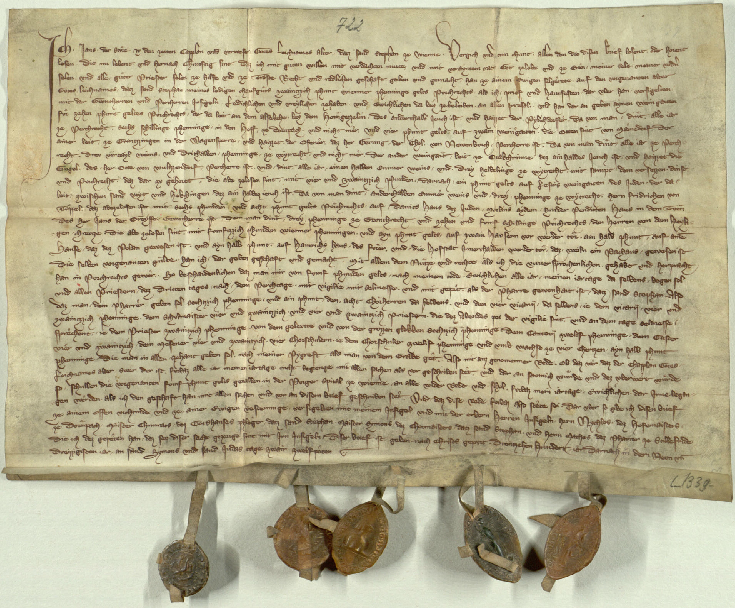

The wording of foundation charters is usually based on traditions that go far back before 1363. Daily and weekly Masses, even when sung, rarely included special musical additions. The most conventional form of liturgical foundation was the “Jahrtag” (anniversary), an annual commemoration of the dead. It comprised a vigil (Matins) on the preceding night, a Requiem Mass in the morning, and then a High Mass on the donor’s day of death. In his foundation charter of 28 October 1339, Jans der Sture, chaplain of the Corpus Christi altar at St Stephen’s, promised for the celebration of his anniversary: 60 d. to the parish priest, 1 tl. (240 d.) in total to eight “canons”[45], 24 d. each to the four vicars, 24 d. each to the schoolmaster, the sacristan, and the sexton, 12 d. to the cantor, 12 d. each to the four choirboys, as well as 60 d. for bell-ringing and ½ tl. (120 d.) for candle wax. In addition, 24 priests were to be present at the vigil during the night and to say the Requiem in the morning, for which they each received 20 d.[46] (» Fig. Choral endowment at St Stephen’s, Vienna, 1339)

The part of such a service sung by the cantor and pupils is never precisely identified in the sources, but as elsewhere, it was probably mainly psalm verses, responsory verses, and certain antiphons (in the Divine Office), as well as Alleluia verses and sequences (in the Mass). The pupils could certainly also sing choral sections together with the priests.

After 1363/1365, there were two cantors at St Stephen’s: the traditional one of the parish school and the new one of the chapter (cf. Ch. Personnel requirements for church music). They are mentioned separately, for example, in a memorial foundation dated 27 September 1378.[47] Here, the canons of St Stephen’s, including their cantor Bartholomaeus, confirm the memorial foundation of the citizen Lienhard der Poll (with Jacob der Poll, chaplain of the town hall chapel, appearing as a witness). In addition to the five chaplains who sing the Divine Office and each receive 35 d., four “choirboys” receive 18 d. each, the schoolmaster 32 d., the cantor 24 d., the accusator (school assistant or beadle) 14 d., the sacristan 16 d., the servants who prepare the altar 16 d., and the sacristan’s assistants who ring the bells receive 6 [small] shillings (= 72 d.) for their wine. The cantor mentioned after the schoolmaster and paid less is the school cantor; the chapter cantor Bartholomaeus is a co-author of the document.

In the testamentary endowment of the professor of medicine Niclas von Herbestorff (25 May 1420) for a weekly Mass in honour of the Holy Cross, it was stipulated under chapter cantor Ulreich Musterer that the Introit Nos autem gloriari and the sequence Laudes crucis attollamus were to be sung “mit der not”, i.e. according to the musical notation in the Gradual.[48] The chants mentioned belonged to the feast days of the Holy Cross (3 May and 14 September). The singing of the (complete) sequence was evidently a special task, even though polyphony is not mentioned here.

Foundation charters often require the involvement of the organ, as does the foundation of Rudolf IV. On 19 August 1402, for example, Dorothea, widow of Jörg Pallnhaymer, promises the “Orgelmaister” (here: organist) 24 d. for the Mass, the cantor likewise 24 d., and each of the four choirboys 12 d.[49]

In an extensive endowment by the brothers Rudolf and Ludweig von Tyrna for the Tirna or Morandus Chapel, established by their family (28 March 1403),[50] no pupils or cantors are required—only the organ. A main feature of the foundation, however, is the establishment of a Sunday Salve Regina during Lent. This highly popular Marian antiphon did not have a fixed place in ritual traditions; here, the reference is probably to an “addition” at the end of Marian Vespers or Compline, similar to the stipulation in the foundation charters of Rudolf IV. Isolated endowments of the Salve Regina, such as that of the future Viennese citizen Heinrich Franck in Bolzano (» E. Ch. The council’s Salve Regina), 1400, became occasions for polyphonic singing over the years.

[44] See Strohm, Ritual, 2014 on the temporal awareness of ecclesiastical regulations.

[45] “Canons” here refers to the “octonarii”, the priests of the collegiate chapter entrusted with pastoral care.

[46] A-Wda, Charter 13391028; see Currency: 1 pound (tl.) = 8 large (“long”) shillings (s.) = 240 pfennigs (d., denarii).

[47] Camesina 1874, 11, no. 36. The distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor is convincingly demonstrated in Göhler 1932/2015, 228 f.

[48] A-Wda, Charter 14200525; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/14200525/charter [02.06.2016].

[49] Camesina 1874, 21, no. 94.

[50] Camesina 1874, 21–23, no. 96.

[1] Perger/Brauneis 1977; Schusser 1986, 17–41.

[2] Zschokke 1895, 2.

[3] Mantuani 1907, 209–210. Flotzinger 1995, 89–90. For general information on organs, see » C. Organs and Organ Music.

[4] Mantuani 1907, 209–210, suspects that the term “organist” refers to an organ builder, who was, however, referred to as “organ master” (e.g. “Petrein the organ master 15 tl” in the city accounts of 1380, » A-Wn Cod. 14234, fol. 39r). This designation is to be understood as a Germanisation of the term magister organorum.

[5] Incorrectly assumed for 1334 by Flotzinger 1995, 90. On the school cantor Peter Hofmaister, see Ch. Development of the Choir School of St Stephen’s.

[6] This and the following information on organs at St Michael’s according to Perger 1988, 91, and the churchwarden accounts in the College Archive of St Michael’s.

[7] On Hans Kaschauer and his father Jakob Kaschauer, who painted the large panel of the high altar between 1445 and 1448, see Perger 1988, 84.

[8] Schütz 1980, 14.

[9] Mayer 1880; Schusser 1986, 66, no. 31/1 (Richard Perger). The university confirmed this regulation on 14 April 1411: see Uiblein, Acta Facultatis 1385–1416, 355.

[11] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 15; Czernin 2011, 59.

[12] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 25.

[13] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1, citing Hauswirth 1879, 29.

[14] See Lind 1860, 11; Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1; Perger/Brauneis 1977, 275.

[15] Mantuani 1907, 289, note 1.

[16] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 1935.

[17] Vienna City and State Archive, Charter 1935, 21 November 1412; see also Schusser 1986, 139, no. 115.

[18] Boyer 2008, 25.

[19] An attempt to distinguish between chapter cantor (“Sangherr”) and school cantor is made by Mantuani 1907, 287 f.

[20] Zschokke 1895, 25–48; Flieder 1968.

[21] Grass 1967, especially 464–467.

[22] Flieder 1968, 140–148, especially 148.

[23] Edited by Ogesser 1779, Appendices X and XI, 77–83. See also Flieder 1968, 155, 158–160.

[24] A statute from 1367 stipulated that the roles of “choirmaster” (magister chori) and dean should be united in one person (Göhler 1932/2015, 141 f.), which, however, apparently did not occur (Flieder 1968, 173 f.).

[25] Mantuani’s (Mantuani 1907, 288) mistaken equation of “choirmaster” with “cantor” has often been repeated. The German term for the latter was “Sangherr”. Ulreich senior (1365?) was “magister chori et cantor” (Göhler 1932/2015, 142 and fig. 11), i.e. the two titles were not synonymous. On the correct use of the terms, see Ebenbauer 2005, 14 f. (choirmaster responsible for the parish), although Mantuani is cited there without contradiction.

[26] On the location of altars and chapels, see Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61–63. I am sincerely grateful to Prof. Barbara Schedl for her advice in this regard.

[27] Ogesser 1779, 80–82. See the list of procession participants from a Liber ordinarius of St Stephen’s (» A-Wn Cod. 4712): » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[28] Zschokke 1895, 30–46; Flieder 1968, 254–266.

[29] Zschokke 1895, 33.

[30] In ecclesiastical service regulations, the Latin equivalent “alta voce” was traditionally used.

[31] Zschokke 1895, 37.

[32] Zschokke 1895, 40.

[33] Zschokke 1895, 84–91.

[34] Raimundus Duellius, Miscellanea, Augsburg/Graz 1724, Vol. II, 78 and 82.

[35] “Ne quis eciam nimium voces agitare aut in altum audeat elevare habeatque et cantum Bassum et nimis clamorosum ad medium reducere.” (Zschokke 1985, 89 f.) See also Rumbold/Wright 2009, 44.

[36] Archdiocesan Diocesan Archive Vienna (A-Wda), Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 107r.

[37] Grass 1967, 482–487.

[38] On 12 March 1421, over 200 Viennese Jews were burned in Erdberg by order of Duke Albrecht V, as reported, among others, by theology professor Thomas Ebendorfer (Lhotsky 1967, 370 f.).

[39] Zapke 2015, 87 f.

[40] Gall 1970, 85–86; Flotzinger 2014, 44–47, 54 f.

[41] Gall 1970, 34, 86 f.; Zapke 2015, 88 f.

[42] Pietzsch 1971, 27 f.

[43] Mantuani 1907, 283 and note 1; Enne 2015, 379 f.

[44] See Strohm, Ritual, 2014 on the temporal awareness of ecclesiastical regulations.

[45] “Canons” here refers to the “octonarii”, the priests of the collegiate chapter entrusted with pastoral care.

[46] A-Wda, Charter 13391028; see Currency: 1 pound (tl.) = 8 large (“long”) shillings (s.) = 240 pfennigs (d., denarii).

[47] Camesina 1874, 11, no. 36. The distinction between chapter cantor and school cantor is convincingly demonstrated in Göhler 1932/2015, 228 f.

[48] A-Wda, Charter 14200525; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/14200525/charter [02.06.2016].

[49] Camesina 1874, 21, no. 94.

[50] Camesina 1874, 21–23, no. 96.

[51] Accounts of the churchwarden’s office of St Stephen’s (in the Vienna City and State Archive), see Uhlirz 1902. Extracts from the account books of St Michael’s in Schütz 1980.

[52] Schütz 1980, 124. Schütz 1980, 15, mistakenly equates the schoolmaster with one of the two cantors.

[53] See Uhlirz 1902, 251 and elsewhere. Knapp 2004, 268, interprets this as a Marienklage (Lament of Mary), which is less likely from a liturgical perspective.

[54] Uhlirz 1902, 364, 384. The Easter sepulchre was an artistically crafted sculpture.

[55] On the locations of the organs, see also Ebenbauer 2005, 40 f.

[56] Uhlirz 1902, 337 (1417).

[57] For example, 1415: Uhlirz 1902, 299.

[58] Uhlirz 1902, 267 (1407).

[59] Vienna City and State Archive, 1.1.1. B 1/ Main Treasury Accounts, Series 1 (1424) etc.: hereafter abbreviated as OKAR 1 (1424) etc. (» A-Wsa OKAR 1-55).

[61] For detailed information on » A-Wn Cod. 4712 see Klugseder 2013; see also » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession. The liturgy of the St Stephen’s chapter is represented by the “Turs Missal” (c. 1430, produced under Provost Wilhelm von Turs), which still belongs to the Archiepiscopal Chapter and is of particular interest for art history.

[62] A-Gu Cod. 756, fol. 185r; see » A. Weihnachtsgesänge.

[63] The former is the earliest dated addition, indicating that the codex must have been created before 1404.

[64] However, the Sunday Vocem iucunditatis was dedicated to St Koloman (» A-Wn Cod. 4712, fol. 54r).

[65] For polyphonic conclusions to monophonic plainsongs, as seems intended here, there is evidence from the fourteenth century in France and Italy.

[66] The procession descriptions in the original corpus of » A-Wn Cod. 4712, a Liber ordinarius of the Diocese of Passau, replicate word-for-word the regulations for Passau itself (courtesy of Robert Klugseder), but are also applicable to Vienna due to the similar ecclesiastical topography of both cities. Added marginal notes clarify the route descriptions with direct reference to Vienna: Klugseder 2013 devotes a separate chapter to the Vienna-related marginalia in Cod. 4712. (See also the digital edition of the Passau Liber ordinarius, http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:cantus.passau). The Corpus Christi procession is represented in Cod. 4712 only by a brief marginal note on fol. 67v. However, the list of participants appears in the appendix (fol. 109r), edited in » E. SL Corpus Christi Procession.

[67] Camesina 1874, 24, no. 101.

[68] Camesina 1874, 26, nos. 113 and 114 (12 and 13 December 1404).

[69] Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50 (Lohrmann).

[70] The claim that the Dorothea Altar stood in front of the rood screen (Perger/Brauneis 1977, 61 and note 214) cannot be derived from the records of 1403–1404. The altar’s income belonged “to the school corporation”, which in this context did not refer to a “brotherhood of pupils” (Lohrmann in Schusser 1986, 75, no. 50), but to the school building itself.

[71] Not to be confused with a canon of the same name, Peter of St Margrethen, active in 1399.

[72] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, nos. 2159 and 3076. 1449: OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 28v.

[73] Some of the information in Brunner 1948 is outdated.

[74] Göhler 1932/2015, 228, no. 98.

[75] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2978; a mention of “Peter Marold, cantor” in OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 19v, may refer to another cantor of the same name or be retrospective.

[76] All except Neuburg are listed in Czernin 2011, 87 f. This list also includes the chapter cantors Ulreich Musterer (†1426), Wolfgang von Knüttelfeld (†1473), Hanns Huber (1474), Brictius (1470s), and Conrad Lindenfels (1479–1488, previously school cantor 1449–1457); a “Kaspar” (1448) may be identical with choirmaster Kaspar Wildhaber (1423/24). The additional names in Flotzinger 2014, 57, note 49, all refer to “choirmasters”, whom Flotzinger, following Mantuani 1907 and Flieder 1968 mistakenly equates with cantors. See Ch. The institutional foundation of the St Stephen’s chapter.

[77] Melk, Abbey Archive, Charters (1075–1912), no. 1436 I 27, http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-StiAM/archive [02.06.2016].

[78] OKAR 5 (1438), fol. 92r.

[79] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 98r, and OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 111r.

[80] The latter note is based on kind information from Prof. Barbara Schedl, Vienna.

[81] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 2656 (3 July 1438). Other, partly contradictory, details cited in Ebenbauer 2005, 38 f.

[82] A-Wda, Charter 14401105.

[83] See also Flotzinger 2014, 56 f.

[84] Boyer 2008, 36 f.

[85] Mantuani 1907, 289 f., note 1. On Martin von Leibitz and his Caeremoniale (A-Wn Cod. 4970), see Schusser 1986, 82, no. 65, and » A. Melk Reform.

[86] OKAR 6 (1440), fol. 97v. The cantor received 60 d.

[87] For example, OKAR 7 (1441), fol. 112v (five weeks; from November before St Martin’s Day to St Lucy’s Day, 13 December).

[88] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 139v. In addition, 24 “peace masses” were sung daily until the Friday after Laetare (4th Sunday in Lent), for which “Hermann and the boys were paid 32 d. for each mass sung”.

[89] For example, OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 140r. The cantor received 21 d. for each “votive”. The dean, levites (probably choirboys), sacristan, and organist are also mentioned.

[90] For example, OKAR 9 (1445). The (unnamed) cantor received 3 s. (= 90 d.).

[91] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 3, no. 3848; Camesina 1874, 92–93, no. 437.

[92] OKAR 8 (1444), fol. 37r.

[93] As often stated in older literature, e.g. Strohm 1993, 507. Corrected in Rumbold/Wright 2009, 47.

[94] Camesina 1874, 78–80, no. 364 (1445, undated).

[95] See Weißensteiner 1993.

[96] OKAR 9 (1445), fol. 51r; the city accounts for 1446–1448 are lost. See Rumbold/Wright 2009, 48–50.

[97] OKAR 10 (1449), fol. 32r.

[98] Mayer 1895–1937, Part II/Vol. 2, no. 3333 (for 1449); OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 41r.

[99] Zschokke 1895, 375; Rumbold/Wright 2009, 50–51. Lindenfels quickly became unpopular after his installation in 1479 by claiming, as chapter cantor, the right to choose his canon’s residence ahead of more senior canons (A-Wda, Acta Capituli 1446–1551, Cod. II, fol. 18r).

[100] OKAR 18 (1461), fol. 82v. The total cost for the carpenter and locksmith (for iron bars to secure the choir books) amounted to 160 d.

[101] OKAR 15 (1457), fol. 118v. The total cost for the carpenter and painter amounted to 95 d.

[102] OKAR 16 (1458); OKAR 36 (1474), fol. 22r.

[103] OKAR 42 (1478), fol. 32v.

[104] Text provided, among others, in Mantuani 1907, 285–287; see also Gruber 1995, 199; Flotzinger 2014, 58 f.

[105] See Strohm 2014.

[106] Uhlirz 1902, 477.

[108] A-Wda, Charter 15060119; see http://monasterium.net/mom/AT-DAW/Urkunden/15060119/charter [02.06.2016].

Recommended Citation:

Reinhard Strohm: “Musik im Gottesdienst. Wien ”, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/musik-im-gottesdienst-wien-st-stephan> (2016).