Size and constitution of the chapel

While the Burgundian court kept daily records of the attendance of the members of the court as a basis for their payment, no such detailed lists have survived for Maximilian’s Austrian court. At best we have records of payment for individual occasions, or for longer stretches of activity, often quarterly payments. While the list of Maximilian’s court drawn up after his death includes nine chaplains, about twenty adult singers and as many boys, this evidently represents a pool of people who could be drawn upon for individual occasions:

Statt des Hoffgesindts/ so nach absterben der Khay: Matt: &c. Hochlöblicher gedachtnus zw Welß Im Monat Januarj des .1519. Jar gemacht worden ist/ Wie hernach volgt.

|

[… 4r]

[… 9v]

Bassisten

|

Altisten

Singer Knaben |

List of the members of Maximilian’s chapel, drawn up after his death in 1519. Vienna, HHStA, OMeA SR 181/3.[21]

Iconographical representations of Maximilian’s chapel suggest that performing ensembles consisted of five to eight men, and four to six boys: see » Abb. Maximilian I. im Dom zu Konstanz.

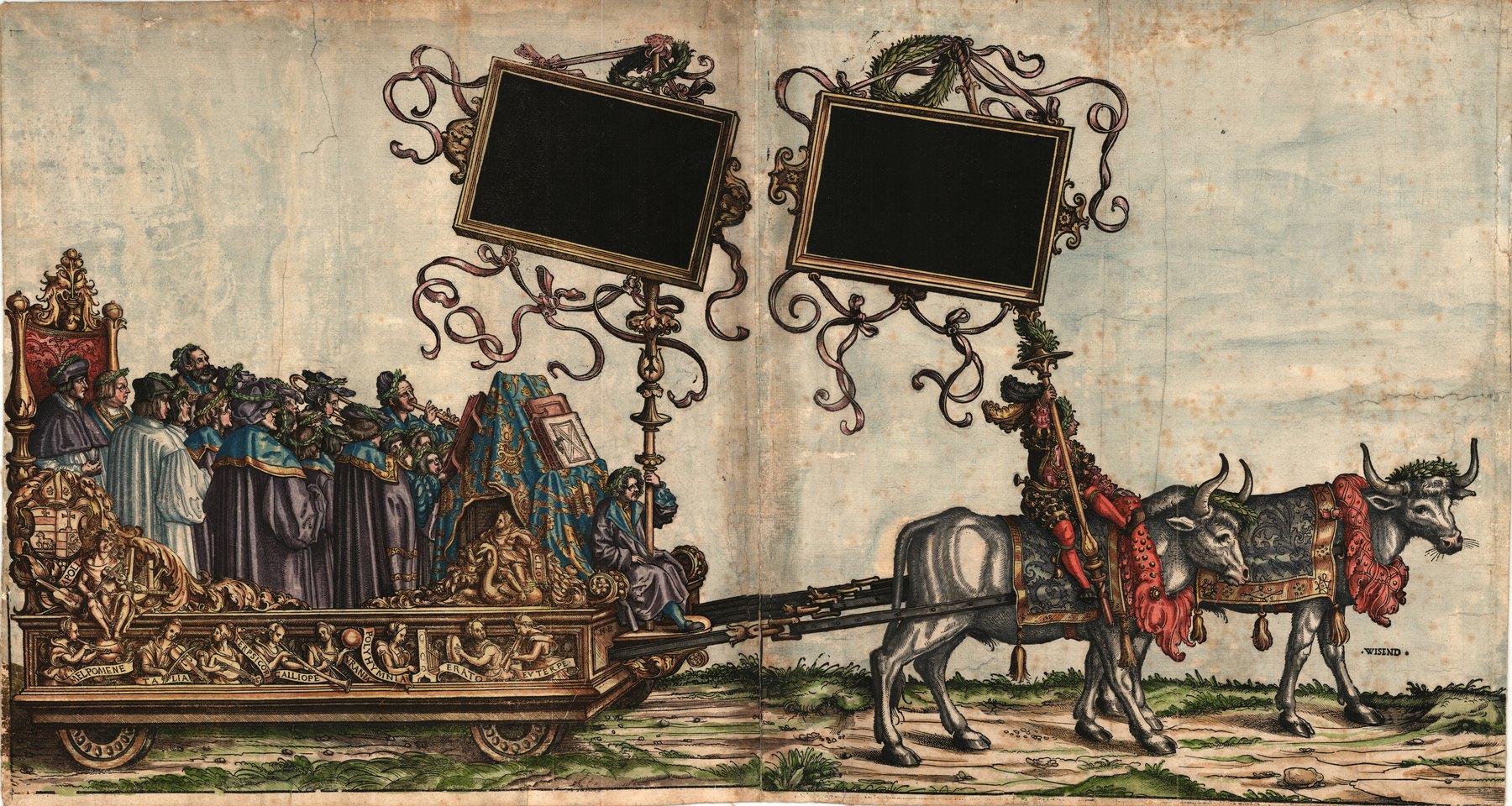

Such sizes suggest that the lower voice-parts were largely doubled, while the upper ones were sung by three or four boys apiece. Iconographical and other archival evidence suggests that some or all of the voices were sometimes doubled by trombones and cornetto: see » Abb. Triumphzug Kantorei.

The singers of the chapel are sometimes mentioned as performing with organ (» Instrumentenmuseum Orgel, Portativ]. The evidence suggests strongly that the organ was not used at this time to double the voices (colla parte), but played in alternation with the voices, improvising over a chant model. The organ could also be used to reinforce the cantus firmus in vocal polyphony, as can be deduced from A-Wn Cod. 5094.[22] Since written polyphony was performed from parts (either in separate books or in a choirbook), colla parte performance would require an organist either to memorise a piece of written polyphony, or to write it out in keyboard score; since no such keyboard scores have survived from this period, it is likely that organists did not routinely accompany colla parte except by reinforcing a cantus firmus, as mentioned above. The transcriptions of vocal originals in the surviving organ tabulatures from the early sixteenth century, such as those of Hans Buchner, Leonhard Kleber and Fridolin Sicher, were evidently intended as solo pieces rather than as accompaniments, since they include only extracts from larger works, depart in some details from the vocal originals, or include such a high degree of ornamentation as to render them unsuitable as accompaniment (see » C. Kap. Gebrauch und Missbrauch der Orgel).

[21] See Koczirz 1930/31. For online images, see https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=11; https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=12

[22] » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs. On alternatim uses of the organ in the liturgy, see Rabe 2019.

[2] See Fiala 2002.

[3] On Lignoquercu’s career at Milan, see Merkley/Merkley 1999, 7, 101–102, 125, 141, 152, 177, 179–180, 242, 251, 285, 288, 290, 293, 296, 371, 373, 376, 391 (here called Ruglerius Lignoquerens).

[4] Wien, HHStA, RK Maximiliana 1 (alt 1a), Konv. 6, 1r–v. Further, see Kooiman/Carr/Palmer 1988. The importance of interpersonal relationships at court has been highlighted in recent historical work; notably, see Hirschbiegel 2015.

[5] Innsbruck, TLA (A-Ila), oö Kammerraitbuch 32 (1492), 30r. Further on court music at Innsbruck in these years, see » I. Music and ceremony in Maximilian’s Innsbruck.

[6] Innsbruck, TLA, Urkunde I 5147/2. Further, see Schwindt/Zanovello 2019.

[7] » A-Wn Mus. Hs. 18810, Tenor, 37r–38v; further, see Gasch 2010.

[9] Alberto Pio da Carpi to Maximilian, 25 June 1513, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Library (US-PHu), Special Collections Ms. Coll. 637, folder 2, 6r–v. Further, see Jacoby 2011. Pietschmann 2019 argues that this motet was written rather for Matthaeus Lang’s entry to Rome in 1514, though this hypothesis seems less likely in the light of the report from Carpi.

[10] See Schlagel 2002, 574–577.

[11] Vienna, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv (FHKA), AHK SB Gedenkbuch [GB] 17, fol. 349r (377r).

[12] Wessely 1956, 121.

[13] McDonald 2019, 21–22.

[14] McDonald 2019, 11.

[15] Wien, HHStA (A-Whh), Reichsregistraturbuch PP 17v–18r; transcr. in Staehelin 1977, vol. 2, 69–70.

[16] Täschinger’s first mass is mentioned in Wien, HHStA (A-Whh), Reichsregistraturbuch AA, 66v–67r; he describes his personal history in a letter addressed apparently to the government of Ferdinand I, now Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Mus.ep. Arigoni, F. Varia 1 (20).

[17] Wien, FHKA AHK GB 4, 111r (135r); Gasch 2015, 368–369.

[18] Innsbruck, TLA (A-Ila), Hs.113, 94r (Nota wen man Speisn sol): “Zwen knaben bej Maister Paulsen.”

[19] Weimar, Thüringisches Landesarchiv, EGA, Reg. Rr. S. 1–316, nº 737, 1a r–v; EGA, Reg. Aa 2991–2993, 10r–11v; further, see Aber 1921, 75.

[21] See Koczirz 1930/31. For online images, see https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=11; https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/bild.aspx?VEID=4016010&DEID=10&SQNZNR=12

[22] » K. A-Wn Cod. 5094: Souvenirs. On alternatim uses of the organ in the liturgy, see Rabe 2019.

[23] See » D. Kap. Zur musikalischen Quellenlage der Hofkapelle Maximilians; » D. Hofmusik Innsbruck. In the sources discussed there, repertory from Flemish composers is well present. See also » F. Musiker aus anderen Ländern.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Grantley McDonald : „The court chapel of Maximilian I“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/court-chapel-maximilian-i> (2019).