The special history of Bohemia and its polyphonic music

The musical tradition of the fifteenth-century Bohemian Lands had its own individual character, influenced by the specific political and religious situation in the country. After the death of Johannes Hus, a popular Czech preacher, university teacher and critic of the contemporary church, at the stake in Constance in 1415, the explosive atmosphere in Bohemia resulted in the Hussite wars (1419–1436). This development had considerable effects on sacred music. On the one hand, the institutional foundation of the Catholic church was broken; many clerics left the country and settled down in the neighbouring regions (i. e. Lusatia, Silesia, Hungary, Bavaria). In the second half of the century, the Catholic church was only partly reestablished as an institution. On the other hand, the ideology of the Hussite reformation supported the development of sacred songs (mostly monophonic in Czech), some of them surviving within the repertories of protestant churches even centuries later (» B. Geistliches Lied, Kap. Patris sapientia). Also, the creation of the liturgy in Czech based on the traditional Roman plainchant in the 1420s can be seen as a prelude to the activities of Martin Luther in the sixteenth century.

The cultivation of polyphony in the late medieval Bohemian Lands was closely connected to the existence of the University of Prague (founded 1348), where the knowledge of mensural theory is documented around 1370 at the latest by a treatise written there by an anonymous author.[1] This local creativity inspired by foreign impulses gave birth to a specific Central European variant of Ars nova music, represented by polytextual motets of the „Engelberg“ type. Among them, there is at least one preserved example of a local isorhythmic motet, Ave coronata/Ave spes.[2] There are several kinds of polyphonic song (cantio), which include a circle-canon called rotulum, pieces that imitate the performance on instruments (trumpetum, stampetum), and canon-like compositons inspired by the genre of the French or Italian chace/caccia (katchetum).[3] Because of a lack of fourteenth-century sources, we learn about this repertory only through late fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sources which document the musical tradition cultivated by the Utraquist Church (followers of the Hussites after 1436), which lasted until the recatholicization which started around 1620. The presence of „archaic“ pieces in those late manuscripts was one of the reasons why the musical culture of Bohemia was until recently thought to have resulted from cultural isolation caused by the Hussite wars, and by the political and religious instability following thereafter.[4]

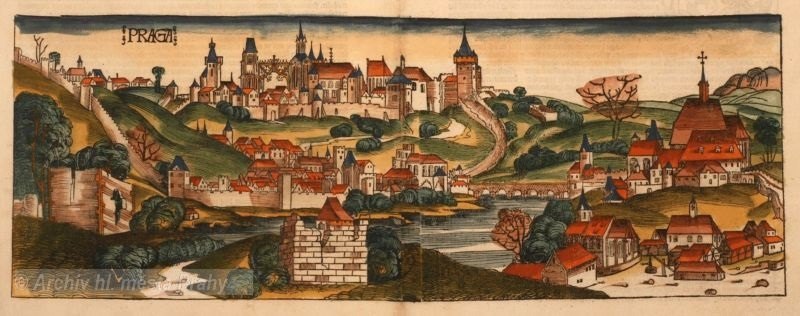

The main Catholic institution was the St Vitus Cathedral in Prague, which had a large ensemble of singers before 1419; but its influence radically decreased after the war.[5] The institution‘s insufficient material background did not allow any other activities than those necessary to celebrate the liturgy.

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 2775.

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[19] Mráčková 2014, 57 ff.

[21] Strohm 1993, 513.

[22] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 263 f., 517.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.