Utraquist church music

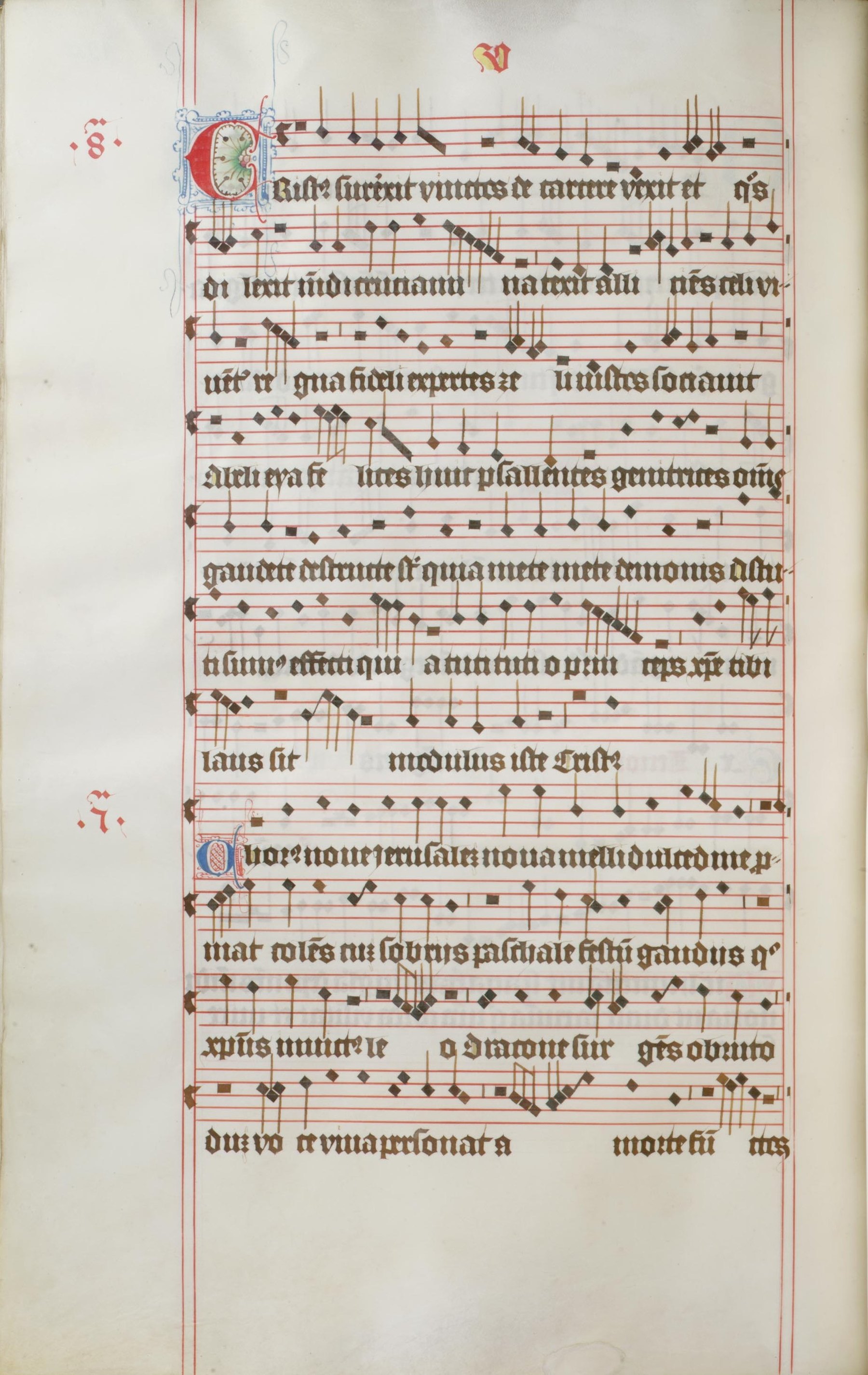

A new chapter of fifteenth-century music history starts with the Utraquist church, which added a novelty to the liturgy – a communion under both kinds for the whole congregation. Concerning the repertory of liturgical music, the Utraquists remained largely faithful to the tradition from the time before the Hussite Wars (i. e. before 1420). As we can conclude from the extant musical sources, a redaction of the liturgical repertory took place during the 1470s or 1480s, which resulted in a specific kind of choirbook called „a Utraquist gradual“.[23] Apart from standard late medieval graduals with plainchant for the Mass liturgy, there are extensive collections of monophonic songs and polyphonic compositions as well, selected and organized according to a common model.[24] A specific feature of Utraquist music culture is a conscious return to the „archaic“ polyphony of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries (including compositions by Petrus Wilhelmi de Grudencz), which is to be found very rarely in the neighbouring regions (e. g. Silesia or Bavaria) after 1450. Polyphonic compositions written in older styles belonged to a core repertory of the school choirs, where they fulfilled mainly a didactic function, partly a liturgical one. At the end of the fifteenth century, when choirs of educated laymen, called litterati, were established, these archaic pieces might also have been sung at their social meetings as generally known pieces from school times. The polytextual motet Christus surrexit vinctos/ Chorus nove Ierusalem/ Christus surrexit (» Hörbsp. ♫ Christus surrexit vinctos) reflects this long tradition; the piece was copied both in the Speciálník Codex and a slightly later Utraquist gradual with polyphonic works, the richly illuminated Franus Codex (» CZ-HKm Ms. II A 6; 1505) from Hradec Kralové (» Abb. Christus surrexit, Franus).

On the other hand, there is no doubt about the active interest of Utraquist intellectuals in the Franko-Flemish polyphony of this time. This kind of music was not only imported (e. g. from France, Italy, Bavaria or Austria) and copied, but it also inspired local composers to write new pieces in this style, even with Czech words.[25] In the Utraquist sources we do not find any polyphonic settings of the Mass Ordinary text of the Agnus Dei, but there are some of them copied without text only or underlaid with a new text (contrafacta), ready to fulfil a different liturgical function.[26] This phenomenon is probably related to the practical implementation of the communion under both kinds to the Mass liturgy.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[1] Černý 2003, 338–341; Witkowska/Bernhard 2010.

[2] Černý 2003, 337; edited in Černý 2005, No. 82.

[3] Černý 2003, 345–354.

[4] For the most actual interpretation of the history of fifteenth-century Bohemia see Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014.

[5] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 262 ff.

[6] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 254 ff.

[7] On the dating, see Gancarczyk 2006.

[9] » I-TRbc 88, » 89, » 90, » 91; » D-Mbs Cgm 810; » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154, respectively. On the relationships between Strahov and Austrian sources see Gancarczyk 2011; on these and other relationships see » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[11] The document of 1460, first described in Staehelin 2006, refers to his appointment to a benefice at Our Lady’s church in Antwerp, probably at the request of the Emperor, who wished to provide his employee with a secure income: see also Benthem 2013a, 71.

[12] See n. 9. The Buxheim Organ Book of c. 1470 is » D-Mbs Mus. ms. 2775.

[13] His compositions are transmitted in Central Europe only; the only exceptions are the song O gloriosa domina and the chanson La plus dolente, if we accept Tourout’s authorship of this piece (see Hlávková 2013a). For concordant sources see Fallows 1999.

[14] See, for example, Benthem 2013a, Benthem 2013b.

[16] As reconstructed in Benthem 2013b, 222.

[19] Mráčková 2014, 57 ff.

[21] Strohm 1993, 513.

[22] Cermanová/Novotný/Soukup 2014, 263 f., 517.

[24] For an overview see Graham 2006.

[25] See, for example, Černý 2005; Vanišová 1989.

[26] For more information see Vlhová-Wörner 2010 and Vlhová-Wörner 2013.

[29] Concordances of the Strahov Codex˙(» CZ-Ps D.G. IV. 47) with the Nicolaus Leopold Codex (» D-Mbs Mus. ms. 3154) and with » I-TRbc 89 and » I-TRbc 91, as well as Italian sources, are discussed in Snow 1968, 99 ff.; Strohm 1993, 512; and Gancarczyk 2013b. See also » F. Regionalität und Transfer.

[32] Edited in Černý 2005, 76 f., 261 ff.

[33] See Strohm 1993, 512, following Sterl 1979, 288.

[34] Pátková 2000, 37.

[36] Pátková 2000, 37; Horyna 2006.

[37]As evidenced by the sources cited in n. 9 above.