The foundation

In 1492, Waldauf began formalising the foundation he had promised on the sinking boat. He developed the concept for the foundation in consultation with Maximilian, his confessor and several theologians. As Maximilian’s entourage travelled around Europe, Waldauf collected thousands of relics which would in time become one of the most impressive collections in Europe. Waldauf supplicated the pope to convince custodians of large collections of relics to donate some to support his pious purpose. Accordingly, in a brief issued on 14 March 1493, Alexander VI commanded archbishop Hermann IV of Cologne to transfer some relics to Waldauf, to encourage the faithful to visit his planned chapel more eagerly. (To carry out this mission, Waldauf would visit Cologne for two months in 1495.) On 10 July 1493, the abbot of Wilhering gave Waldauf – accompanied by Nicolas Mayoul, the head of Maximilian’s chapel (“Seiner künigklicher genaden Obristen Caplan”) – a fragment of the true cross.

This fragment, the most prestigious relic in Waldauf’s collection, may have served a particular purpose. Throughout the Kingdom of France there were several collegiate foundations called Saintes chapelles, of which that in Paris was only the most famous. By definition, a Sainte chapelle was a foundation established by a member of the (extended) royal family, containing a relic of the Passion. In many cases this consisted in a piece broken from the crown of thorns, the prize relic at the Sainte chapelle in Paris. In the Heiltumbuch (Ms., Haller Heiltumbuch, Pfarrarchv, Hall i.T., » ) the foundation’s home is often described as a heilige Capelle. If the epithet heilig here has a specific meaning rather than a general one, it is possible that the chapel in Hall – to which Maximilian stood as a second founder beside Waldauf – was intended as a Habsburg equivalent to a French Sainte chapelle.

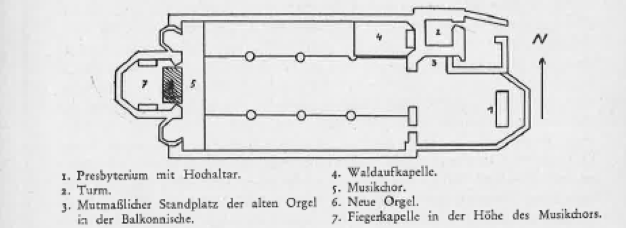

Although Waldauf’s relics were initially housed in his castle of Neu-Rettenberg (completed in about 1494), he soon realised that the collection, intended to bring spiritual benefits to the public, required a more public setting. Waldauf decided not to build the chapel for his foundation at Innsbruck, where it might be seen as competing with Maximilian’s building projects, but rather in the commercially important city of Hall, location of a significant salt-works and the imperial mint, as well as a stop on the transalpine way across the Brenner pass. The parish church of St Nicholas in Hall was already home to an important liturgical foundation and chapel, established by Hans Fieger the Elder, a citizen of Hall who had made a fortune from silver mining at nearby Schwaz. (Vgl. » Abb. Plan von St. Nikolaus, Hall in Tirol.)

Construction of Waldauf’s chapel in the church began in 1493. It is divided from the rest of the building by a splendid wrought-iron grate bearing the heraldic arms of Waldauf and his wife Barbara Mitterhofer, whom he married in 1491 (» Abb. Kapellgitter Waldaufkapelle Hall i.T.).

Waldauf paid for charters from bishops, cardinals and popes that would guarantee indulgences to those who duly performed their devotions in this chapel, even if Hall were placed under interdict. For the family crypt beneath the chapel, Waldauf procured indulgences equivalent to those of the Campo Santo in Rome. (To be sure of the efficacy of this blessing, Waldauf even had the floor of the crypt sprinkled with earth brought specially from the Campo.) In the central shrine of the altar was a statuary group representing the Coronation of the Virgin. Donor panels to the side – attributed to Marx Reichlich and now housed in the city museum at Hall – depicted Waldauf and his wife Barbara. Waldauf is presented by SS Florian and George, and his wife by St Barbara and Bridget of Sweden. The chapel was also richly decorated with silver and gold plate, and precious carpets.

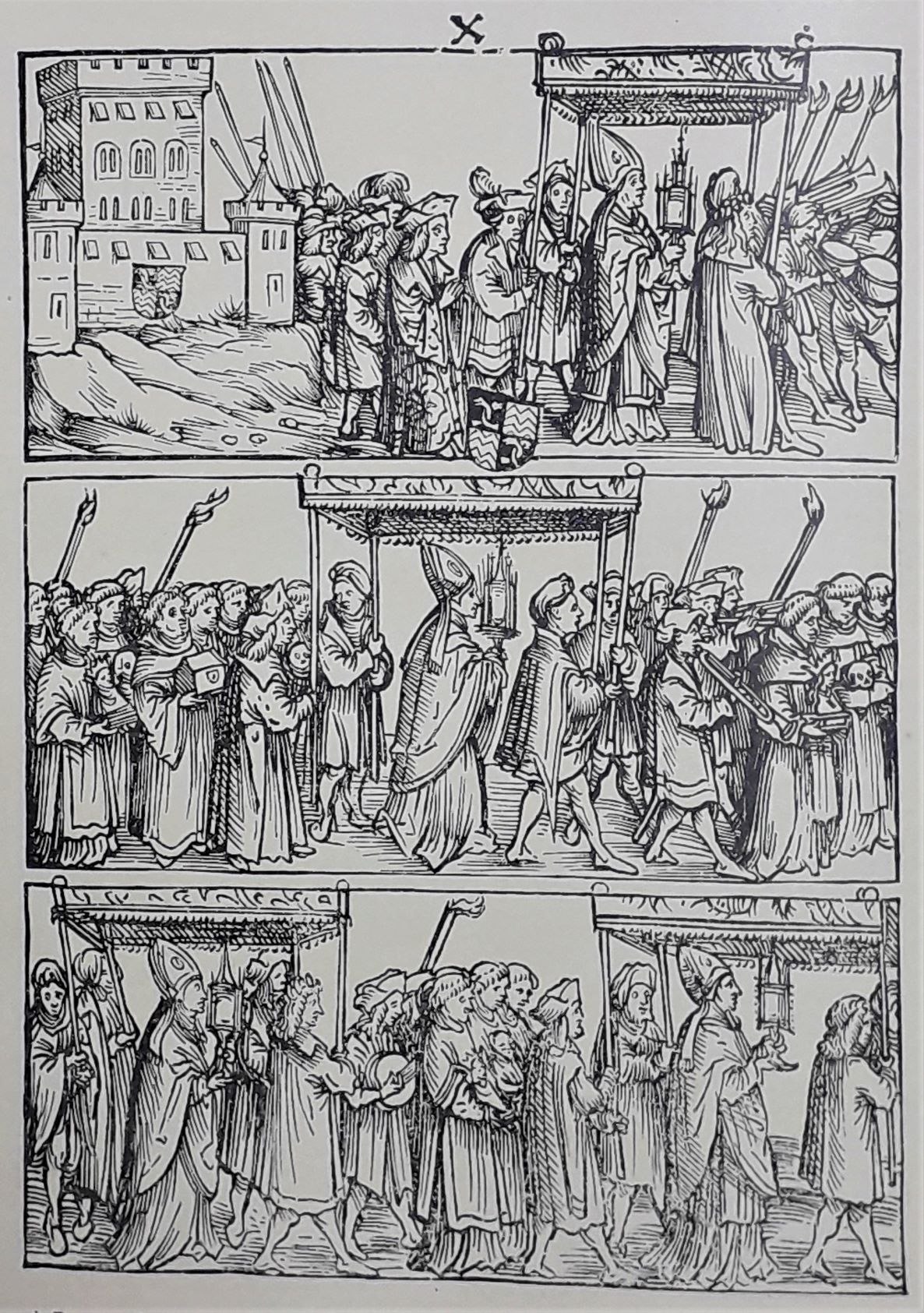

The foundation was inaugurated on 14 February 1496, but work did not stop there. Its endowment and structure were refined in further documentation, culminating in the great letter of foundation dated 29 December 1501.[8] Many of these documents emphasise Barbara Mitterhofer’s role in supporting the endeavour. Others indicate that the foundation was supported actively by Maximilian and his wife Bianca Maria, and by Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. By 19 January 1501, construction of the chapel was sufficiently well advanced that the altar could be officially dedicated, and some of the relics brought from Neu-Rettenberg. On 9 May 1501, the relics were displayed in procession. According to the account in the Heiltumbuch, an improbable (and improbably precise) total of 32,784 people witnessed this procession, though it is likely that many of those had come to Hall simply for the spring fair rather than specifically for the procession. A woodcut made by Hans Burgkmair the Elder for inclusion in the Heiltumbuch shows several musicians in the procession (vgl.» Abb. Haller Heiltumprozession): trumpeters and timpani, a group of singers performing from books and a lutenist. (Outside, the lute would have been virtually inaudible from any distance, and may simply have kept the singers in pitch.)

The Heiltumbuch notes that the singers included the schoolmasters and pupils from Hall, Innsbruck, Schwaz and other towns in the Inn valley.

The great charter of 29 December 1501 prescribes that the foundation was to employ a senior and a junior chaplain. The benefice of senior chaplain was one of the best endowed in the empire. (The salary for the chaplains and musicians was derived primarily from an endowment of 80,000 Gulden, primarily from the rents on rural properties which Waldauf purchased for this purpose, and income from the deanery in Ambras and the salt-works at Hall, which Maximilian had diverted for this purpose in 1497. The sale of letters of indulgence was an important secondary source of income.) The senior chaplain was obliged to preach three times a week during Advent, and daily during Lent. Moreover, he was obliged to say a requiem mass for the Waldauf family weekly. The chaplains’ house contained a library, where the books were chained to the wall. The chapel in the parish church in Hall was soon found to be too small, and a free-standing building was constructed in the churchyard in 1503, where it stood until destroyed by an earthquake in 1670.[9]

On the north façade of the church, Waldauf had a two-storey wooden frame (“tabernaculum”, “Heiltumstuhl”) constructed for the exposition of relics on specified feasts, usually coinciding with a major market. This construction was modelled after one in Nuremberg, which Waldauf presumably saw in use during the imperial diet in 1491. The music during such expositions was supplied by trumpeters, trombones, pipers and choirboys. Soon the number of visitors to these events increased to such an extent that a team of chaplains had to be employed to cope with the numbers of those who wished to make their confessions, a necessary precondition for receiving the indulgences offered to those who paid their devotions.

At first, the music for the masses and offices specified by the foundation was presumably provided by a group of boys from the Latin school. In 1497, Maximilian augmented the provision of an organist and the singing of polyphonic music under the direction of the Latin school master at Hall (see below). (Between 1512 and 1519, the schoolmaster at Hall was Petrus Tritonius, known for the humanistic ode settings he wrote at the encouragement of Conrad Celtis.)[10] The singers were to perform polyphonic music (in mensuris) at vespers, mass and other services, not merely on Sundays and feast days, but on weekdays as well. In particular, they were to sing the Salve regina every evening. The repeated emphasis that Maximilian’s deed gives to the performance of music in mensuris suggests that the singing to that point may have comprised chant only. Maximilian’s foundation for the singing of the antiphon Salve regina is possibly an importation of the practice of the Salve-service, also known as Salut or Lof, popular in late mediaeval France and the Low Countries, which included not only the singing of the Salve regina, but also other music, including psalms and organ music, often in alternation with the chorus. Endowed Salve regina services are also known from other towns in the Austrian region, for example at Bozen (1400) and at St. Stephen’s, Vienna.[11]

The names of the organists who played for the foundation’s services are not known. (Unfortunately, the earliest surviving account books from the foundation date from 1733.) In 1499, Paul Hofhaimer received a payment from the city council of Hall, but it comprised only four pounds of fish and four measures of wine, which suggests a one-off appearance rather than a regular arrangement (Stadtarchiv Hall in Tirol, A-HALs, Raitbuch 8, f. 587r). It is possible that this appearance was not even in the context of Waldauf’s foundation; the record does not specify why he was paid. Nevertheless, given Maximilian’s involvement in the foundation, it is not unlikely that Hofhaimer had some involvement in the project. It is even possible that Hofhaimer’s surviving organ versets for the antiphons Salve regina and Recordare virgo mater – transmitted in the tablature books of Fridolin Sicher (» CH-SGs Cod. 530, copied 1525) and Leonhard Kleber (» D-Mbs Mus. ms 40026, copied 1520–1524) respectively – were written to permit a student unskilled in improvisation to supply the music required by the statutes of the foundation.[12] Hofhaimer was famous for his skill in improvisation, and there is no obvious reason why he would need to write down such settings except for the benefit of others.

Maximilian’s support for Waldauf’s foundation has been mentioned several times. Some of the documents of foundation also note the involvement of his wife Bianca Maria Sforza. His son Philip the Fair also visited St Nicholas in Hall on 15 September 1503, and his chapel sang in the church. This visit is commemorated by a woodcut in the Heiltumbuch: vgl. » Abb. Maximilian I., Philipp der Schöne und Florian Waldauf in Hall.

Ten days later, Philip issued a document confirming the foundation. This ratification of the rights of the foundation reinforced the close bond between the Waldauf chapel and the Habsburgs.

[8] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 304; digest in Moser 2000, 96–102.

[9] Moser 2000, 32.

[10] Further on Tritonius, see » Kap. Humanists and musicians.

[11] See » Kap. Das Salve regina des Rats; » Kap. Musikalische Stiftungen bis ca. 1420. There is every possibility that such ceremonies included polyphonic singing from the early part of the century.

[12] » Kap. Orgelmusik Hofhaimers, » Hörbsp. ♫ Recordare, Hofhaimer.

[1] Moser 2000, 11.

[2] Moser 2000, 12.

[3] Moser 2000, 13.

[4] Abkürzungen: GW: Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke. Stuttgart: Hiersemann, 1925 ff. http://www.gesamtkatalogderwiegendrucke.de. VD16: Verzeichnis der im deutschen Sprachbereich erschienenen Drucke des XVI. Jahrhunderts. 24 vols, Stuttgart: Anton Hiersemann, 1983–2000. www.vd16.de.

[5] Similar catalogues appeared for the Vienna collection in 1502, and the collection of the Saxon Elector Friedrich at Wittenberg in 1509, with woodcuts by Lucas Cranach the Elder; » Kap. Das Wiener Heiligtum.

[6] Ed. Garber 1915.

[7] Moser 2000, 18–40.

[8] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 304; digest in Moser 2000, 96–102.

[9] Moser 2000, 32.

[10] Further on Tritonius, see » Kap. Humanists and musicians.

[11] See » Kap. Das Salve regina des Rats; » Kap. Musikalische Stiftungen bis ca. 1420. There is every possibility that such ceremonies included polyphonic singing from the early part of the century.

[13] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 29, digest in Moser 2000, 75–76.

[14] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 273, digest in Moser 2000, 78.

[15] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 437; later copy in Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Urkunde 274; digest in Moser 2000, 80–81.

[16] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 34; digest in Moser 2000, 81.

[17] Hall in Tirol, Stadtarchiv, Waldaufstiftung Urkunde 44; digest in Moser 2000, 90.

[18] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 437; digest in Moser 2000, 112–114.

[19] Hall in Tirol, Pfarrarchiv, Urkunde 484a; digest in Moser 2000, 118–121.

[21] Incunabula short-title catalogue (The British Library, https://data.cerl.org/istc/_search). See Rudolf 1957; Merlin 2012.

Empfohlene Zitierweise:

Grantley McDonald : „The Waldauf foundation at St Nicholas’ church, Hall in Tirol“, in: Musikleben des Spätmittelalters in der Region Österreich <https://musical-life.net/essays/waldauf-foundation-st-nicholas-church-hall-tirol> (2019).